Regent's Park, London

Nature Worship

In the middle ages, an area of land just north of the centre of London, owned by a monastic community and known as Marylebone Park, was in existence. When Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries between 1536 and 1541, he appropriated the area and from then onward, he and his courtiers went there to hunt deer, hang out and generally enjoy life. Later monarchs enjoyed hunting there until 1649, after which it was let out to small farmers who produced milk and other comestibles to sell to the townsfolk. In 1811, the Prince Regent commissioned architect John Nash to redevelop the park and its immediate surroundings. Nash put forth the idea of building fifty “country” villas on an area immediately east of the park. His idea was to situate each villa so as to give the illusion to every occupant that his or her dwelling had the entire park to itself. Regent’s Park was landscaped and plans were laid down to build a “pleasure pavilion”. The development was intended for the very rich, catering to their desire to be apart from the common people. The occupants would have the best of both worlds, living in town but constantly reminded of what they thought of as countryside. One way or another, parks and gardens like Regent’s Park idealized rather than recreated nature.

Since the eighteenth century, many of Europe’s intellectuals had been influenced by the writings of the French philosopher, Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1788). Rousseau, whose doctrines partly gave rise to the French Revolution, theorized in books like Discourse on the Arts and Sciences that many of the social evils he witnessed were the result of society becoming too sophisticated and that that sophistication corrupted men. He believed that advances in science were creating poverty and inequality, expounded in the stirrings of the Industrial Revolution. The sum of his argument was that in order to regain his earlier purity and simplicity, man had to draw closer to nature. Of course, people interpreted this supposed return to the primal state in a great variety ways. It could have meant spending the occasional day in the countryside or going to live entirely in a “rustic” cottage. For the French Queen Marie Antoinette, it meant dressing up as a milkmaid and milking cows into a porcelain bucket on her Versailles estate. For a number of privileged people in London, it meant buying a splendid town villa that overlooked the landscaped and well-maintained Regent’s Park.

Nash’s plans did not stop at the park or the terraces that he laid out. Just south-east of the development, he laid out London’s Regent’s Street, a grand boulevard by which to connect the projected pleasure pavilion and Carlton House (residence of the Prince Regent) a mile further south. However, the pleasure pavilion was never built. Carlton House was demolished and Buckingham House was rebuilt as Buckingham Palace. It was and still is the main residence of the monarch. Regent’s Street is still London’s “only boulevard” and Regent’s Park is still in existence. Today, it has a zoo and a boating pond and a number of beautiful flower gardens, in addition to several sports’ facilities and an open-air theatre.

Unorthodox References

In his book, The City as a Work of Art, Donald J Olsen explains that in spite of his careful planning, John Nash’s “Regent” project did not meet with immediate success. He describes the Nash terraces as “outrageous” in relation to anything that had been built in London before. Walking along Cumberland Terrace today, it is very difficult to feel “outraged” by the creamy facades of the sedate and elegant town villas. Of course, I am writing this over two hundred years after they were built, two centuries that have seen seismic changes in building techniques, design and architecture. Nash used the classical references on the facades of the buildings in new and radical ways. Today, the houses are very desirable town residences but the denizens of the early 1800s saw matters rather differently.

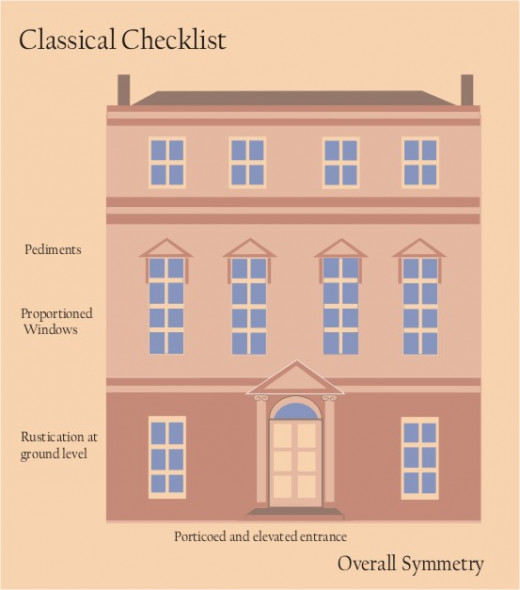

Typical Classicism

Classicism had been in vogue in Britain since 1622, when architect Inigo Jones returned from Italy and rebuilt the Banqueting Hall on London’s Whitehall. Few people are unacquainted with classicism but broadly speaking, the way to recognize a classical building is by its proportions and references. The classical building is inclined towards symmetry, usually with a porticoed entrance door in the centre of the ground-floor storey. Depending on the grandeur of the building, there is often an elevation of steps to the entrance and columns may support the portico. The ground level storey is often “rusticated”, that is, built of thicker, coarser blocks than those from the first storey and upwards. The windows are usually rectangular, made of multiple panes and to a particular proportion known as the “golden mean”. Often, the windows are pedimented, that is, bearing triangular semifunctional overhead ornamentations.

Jones, of course, had learned about classicism while witnessing the effect that the Italian Renaissance had upon European building. The Renaissance had seen a revival in the styles of building beloved of the Romans. In turn, the Romans had derived their building references from the standards in aesthetics established in classical Greece. And the Greeks? There are many legends surrounding how this civilization developed its very beautiful way of building, for example, resting beams of wood resting across wooden posts or even actual trees to form walls and roofs. What is undoubted is that Grecian architecture reached its zenith alongside its actual civilization, evolving from the “primitive” into something very grand. Hundreds of years later, classical buildings had become the desirable, urban architecture. After Jones had redesigned the banqueting house, the “Italianizing” of London begun. The rebuilding of London after the great fire of 1666 augmented this. Throughout the next 100 years, the fashion for classicism waxed and waned, but a revival of “neo-classicism” in the late 1700s saw fine country houses and town villas built all over Britain, a fashion that lasted into the early 1800s.

It is no wonder that Nash thought that he could not lose. Regent’s Park was situated a few miles north of the river Thames, a most unsanitary waterway until the latter half of the nineteenth century. Really, it was the ideal spot on which to build villas for the wealthy. In spite of all of his careful planning, however, public disdain combined with an economic downturn meant that the “Regent” project did not meet with early success. What is more, the Victorian age was dawning and with it came the outpourings of writer and aesthete, John Ruskin (1819-1900), who held sway over public opinion in matters of taste in art and architecture. In his best-selling book, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, Ruskin wrote about the foul torrent of the Renaissance, meaning the British resurgence in classical architecture. By the middle of the nineteenth century, writer Charles Dickens was using architecture, especially that of London, as a metaphorical vehicle for his stories. In novels like Bleak House, he created sweeping social contrasts with unhappy characters living in grand, classical country mansions and town houses. Deluded and self-deceiving people occupy scenes of urban decay and ruin, while the happier characters occupy “rustic” houses and cottages, the kind of building that John Ruskin would have approved of. The public appetite for “country” cottages continued into the early years of the twentieth century. Because of this, the Regent’s Park development took an unexpected turn.

We now recognize Regent’s Park as the prototype of the “garden suburb”, areas of housing interspersed with green spaces. Of course, the typical contemporary suburb barely resembles Nash’s development. But we did manage to hijack the idea of rows of sedate houses, set in semirural surroundings. Meanwhile, Nash’s villas are very desirable urban properties today and the layout of Regent’s Park continues to reflect the grandeur of old, with its geometric layout, cultivated flowerbeds and classical statuary.

Sources

Bleak House by Charles Dickens

The City as a Work of Art (London, Paris, Vienna) by Donald J Olsen (Yale University Press)

The Seven Lamps of Architecture by John Ruskin (courtesy of Project Gutenberg)