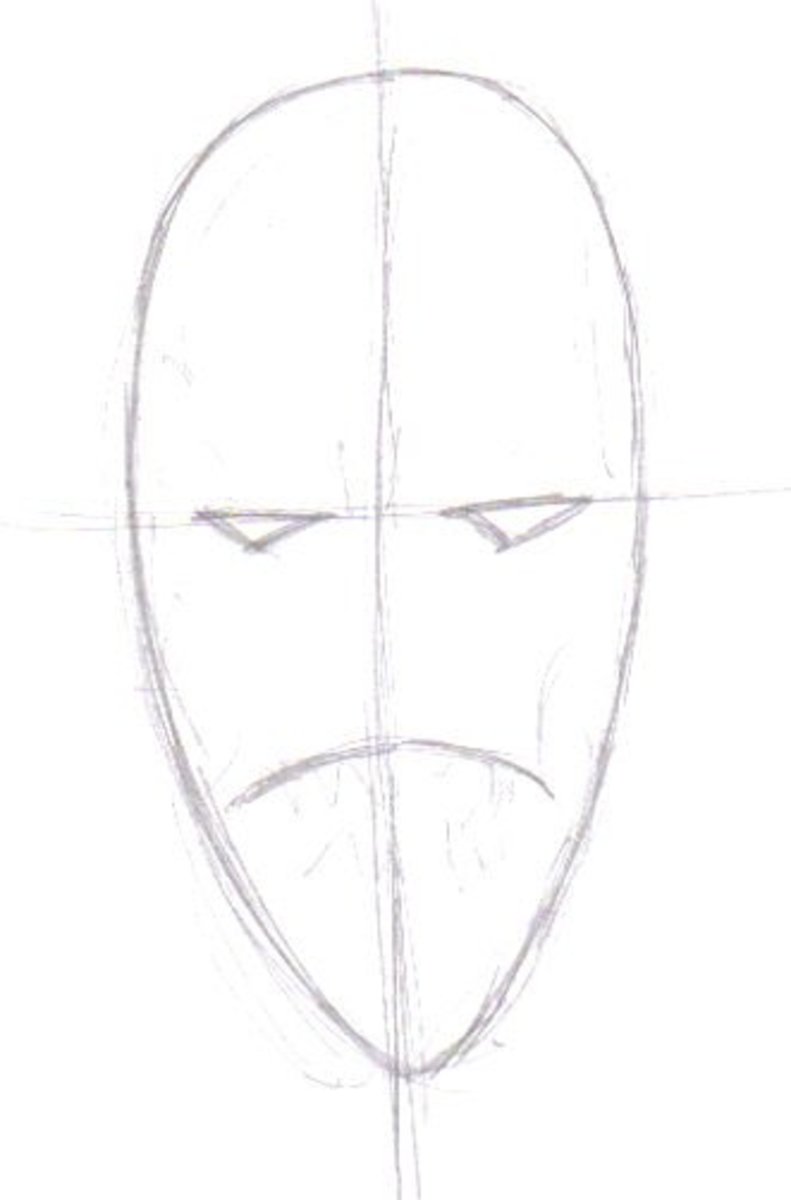

How To Draw Caricatures

Caricature in the pictorial arts, are a representation, ordinarily of a person or a type of person, made unliteral (and usually grotesque or ludicrous) by the exaggeration of certain features. The term, derived from Italian caricatura ("loading," "charging"), is also applied to works in other arts, but thesej are more often termed "burlesque" or "parody."

Caricature depends for its effect on dissimilarity from a recognizable original; the distortion or simplification, reflecting the artist's point of view, usually comments on the character of the subject. Because exaggeration of the human features is ordinarily uncomplimentary, caricature lends itself to satiric uses, but it is sometimes intended quite innocuously.

Origins

Caricature originated in the Renaissance. Champfleury, in his Histoire de la caricature antique (1865), erroneously maintained that caricature goes back to ancient times. He cited classical zoomorphic drawings of people as being caricatures, but these drawings lack the "charge" of caricature since they do not illuminate for the viewer the characters of their subjects. They are merely burlesques, drawings intended only to amuse through incongruity.

The usual simplicity and didactic intent of caricature made it suitable to wide audiences and its development in the Renaissance coincided with that of various techniques (woodcut, etching, engraving) for producing multiple impressions of a single drawing. Caricature in its most familiar form (the satiric representation of individuals or types) first became important in the 16th and 17th centuries with such artists as Agostino Carracci (1557-1602) and Giovanni Bernini (1598-1680). One of the best caricatures of the 16th century is a German woodcut showing a glutton trundling his own stomach along in a wheelbarrow and vomiting.

Caricatures centering on political issues flourished in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. Among their controversial subjects were the rise of Lutheranism, the Mississippi Bubble, and the antipathy in England between the Hanoverians and the Jacobites. Two of the outstanding caricaturists of the 18th century were Giovanni Tiepolo (1696-1770) and William Hogarth (1697-1764). Both of these artists usually caricaturized types rather than individuals; an exception is Hogarth's portrait of the Jacobite Lord Lovat at his trial in 1745.

Early 19th Century

The 19th century was the golden age of caricature. The popularity of this art form was stimulated by Thomas Bewick's refinement of the art of wood engraving in the 18th century and by Aloys Senefelder's invention of lithography about 1798. These techniques, making it possible to print thousands of impressions of a single caricature, caused a flowering of the art. Both in the quantity and in the quality of their work, the caricaturists of the 19th century have never been equaled.

The finest English caricaturists at the beginning of the century were Thomas Rowlandson and James Gillray. Rowlandson (1756-1827) began his career as a watercolorist and portraitist in oils, but about 1781 he turned to comic drawing. He did not produce many genuine caricatures, being content for the most part to burlesque the manners of the day. The exceptions include his etching of the boxing match between Quirk and Ward (1812), which clearly shows not only the scene but the artist's attitude toward the boxers and the spectators. Rowlandson's works are characterized by imagination and a boisterous humor.

Gillray (1757-1815) was famous for his caricatures on social subjects, especially political questions, to which he devoted himself for the most part from 1780 to 1811 (when he lost his sanity). Gillray's drawings, like those of most other early caricaturists, are crowded with incident: they must be "read" rather than observed. His technique was bold and vigorous and his satire often savage. His brutal drawing of Czar Paul I of Russia was one of the earliest of portrait caricatures, which during the late 19th century became the dominant mode of caricature art in England.

Poverty forced George Cruikshank (1792-1878) to begin drawing professionally at the age of 13, and in the 1810's he was producing caricatures for several English papers. His manner echoed that of Gillray, but Cruikshank was more genial and less skillful. In the early 1820's, guided by the British preference of the comic to the satiric, he turned chiefly to book-illustrating, which brought him considerable fame later in the century.

Late 19th Century

England. Caricature in England was revived by an Italian, Carlo Pellegrini (1839-1889), who went to England in 1864. Pellegrini refined the portrait caricature, purging it of the symbolism that French caricaturists had given it. At first he published his drawings over the signature "Singe"; in 1869, when he became a regular contributor to Thomas Gibson Bowles's Vanity Fair (founded in 1868), he began to sign himself "Ape."

Vanity Fair boasted other caricaturists, including "Spy" (Sir Leslie Ward) and the most famous of all English caricaturists, Max Beer-bohm (1872-1956). Beerbohm, who also contributed to the Yellow Book and the Savoy, published four books of caricatures, beginning with Caricatures of Twenty-five Gentlemen (1896). His work, although it reveals Pellegrini's influence, is unmistakably individual. His graceful drawings possess to a high degree the frivolity he considered essential to the art.

France. After the 1850's a new and more frivolous variety of caricature, social comedy, developed in France. New papers were founded, including the Journal amusant, Le Rire, Le chat noir, and L'assiette au beurre; and new artists, among them Caran d'Ache, Toulouse-Lautrec, Jean Louis Forain, and Theophile Steinlen, came to the fore. Their favorite target was the beau monde: the newly rich bourgeoisie, the nobility, the crowned heads of Europe, the stars of the theater, the mistresses of kings, all were subjected to the caricaturist's pen. Meanwhile, the satirists were gaining sympathy for the lower classes. Shop girls, domestic servants, and working men began to figure in their drawings in the 1870's. The energetic and hardhitting Steinlen, in his Chansons rouges, depicted the Parisian proletariat with all its latent power.

United States. Caricature has never been very strong in the United States. Thomas Nast (1840-1902) was a political cartoonist rather than a caricaturist, although there are strong elements of caricature in his famous attacks (1869-1871) on the Tweed Ring at New York City's Tammany Hall. American political cartoons were usually allegorical, and a tendency toward allegory is visible even in the work of Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944), who approached genuine caricature in his series called Life's Comedy.

Middle 19th Century

France. During the 18th century, caricatures had ordinarily been sold to printsellers; but early in the 19th century caricature became attached to the profession of journalism. The first great journal of caricature was French: La Caricature, a weekly founded in 1830 by Charles Philipon. Because La Caricature espoused Republican views, it soon acquired a formidable array of caricaturists, among them Jean Grand-ville, Henri Monnier, C. J. Travies, Paul Gavarni, and Honore Daumier. But it also attracted the hostile attention of Louis Philippe's government, which suppressed it in 1834. Its place was taken by a daily, Le Charivari, which Philipon had founded in 1832.

Philipon (1800-1862) was the creator of one of the great caricatures. Having used a pear to symbolize Louis Philippe, he was taken to court for libel, and in his defense he produced a four-part drawing. The first part accurately depicted the monarch's broad jaws, heavy jowls, and multiple chins below a head that narrowed toward the crown; in the second and third parts these features were gradually simplified and exaggerated until, in the fourth part, Louis had become nothing but a pear with vestigial eyes, nose, and mouth.

Philipon's most remarkable artist was Honore Daumier (1808-1879), the greatest of all caricaturists. Daumier's wide-ranging mind detested humbug, hypocrisy, and injustice in all their forms, and he attacked them with superb draftsmanship and composition. He took all of Parisian life as his province, but he concentrated on such evils as fraud in high places and smugness in the body of society. Among his most notable works are the lithograph Enfonce Lafayette and the magnificent series Le ventre legislatif. Daumier's career continued through the Franco-Prussian War, and his last important work, the Album du siege, is a threnody on devastated Paris.

Germany. Caricature became important in Germany about the middle of the century. Die fliegende Blatter, the first of many German satirical papers, was founded in 1844 by Kaspar Braun and Friedrich Schneider. Unlike their French counterparts, the German magazines underplayed political and social comment, focusing instead on manners and morals. The German style also differed in two important respects. Whereas the French employed pen, pencil, watercolor, and gouache, the Germans tended to use pen only; thus, most of the German drawings were done in simple line. Further, the Germans generally avoided captions, so that their drawings had to speak for themselves. This convention led to the development of the sequential caricature made up of as many as six different drawings, each illustrating one stage of a story.

One of the early masters of this genre was Wilhelm Busch (1832-1908), who belonged to the staff of Die fliegende Blatter from 1859 to 1871. Busch was Germany's finest caricaturist, although his drawings often leaned toward the merely comic. His famous series Max und Moritz led to the development of the American comic strip; its influence is especially apparent in the early Katzenjammer Kids, which would not have appeared out of place in the 19th century German magazines (see comics). Among Busch's colleagues, Adolf Oberlander, Adolf Hengeler, and Emil Reinicke were also influential.

England. Punch, the most famous of all humor magazines, was founded in London in 1841. British caricature was then declining, and Punch did little to revive it. Clever political cartoons occasionally appeared in its pages (the best-known is Sir John Tenniel's Dropping the Pilot) but for the most part its drawings merely illustrated dialogue captions. The magazine never published a caricature that could have disturbed British bourgeois complacency.

The 20th Century

After World War I, caricature entered a general decline. This was probably caused by changes in the media of information, particularly the growing use of halftone photoengravings in magazines and newspapers.

Another possible cause was the political changes that took place after the war; monarchies toppled and were replaced by multi-party political systems. The caricature of policy, which implies a unified national view, gave way to political cartooning, which implies a party view; and anything so narrow as party politics offers the caricaturist meager scope.

Today caricature appears to be reviving.