- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

American Civil War Life: Union Infantryman – Life In Camp 5

“I commenced writing yesterday, but was obliged to stop to attend drill, a very common incident in soldier life. The first thing in the morning is drill, then drill, then drill again. Then drill, drill, a little more drill. Then drill, and lastly, drill. Between drills, we drill, and sometimes stop to eat a little and have a roll call…

“We are drilling very severely, almost all the time. Two hours every morning with our knapsacks on, which is very hard work, and the rest of the day is mostly spent in battalion and brigade drill. Every time we go out we have some twenty or twenty-five pounds (9 kg or 11.25 kg) weight to carry, and carrying it so long is no boy's play.”

- Oliver Wilcox Norton, 83rd Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861

Routine: The Day In Camp

Every camp was somewhat different from others, so it is difficult to illustrate a “typical” day in camp, but there were enough similarities, in which all camps abided, to give a fairly accurate portrayal.

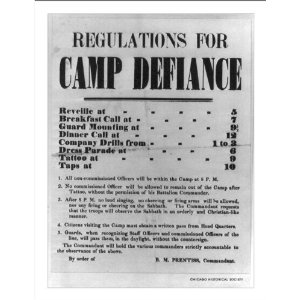

The day began with a prolonged bugle call from one of the Regiment’s field musicians. This was called Reveille, and it was the official wake-up call for the army. This occurred at 5:00 am (0500) during spring, summer, and fall seasons, and at 6:00 am (0600) during the winter. Non-commissioned officers (NCO’s) were unsparing in their desires to roust the troops from their blankets, so if the bugle call didn’t get the men to their feet, the sergeants did.

Immediately after the rousting, the men were expected to line up for the Company Roll Call. There was little order needed for this line, so long as it was in a single rank and aligned with the Sergeant. He was the first on the line, on the right flank, as it faced forward. The troops needed to adhere to a modicum of a dress code, so each soldier was required to wear his headgear as well as his fatigue blouse with the top button fastened. Depending on the whims of the commanding officers, there could have been different expectations of dress for the Roll Call, but those I have described were the minimum expectations. No equipment or weaponry was needed.

The First Sergeant then stood in front of the line and called out the names of the men in the Company. Each man on the line responded to his name with “Here” or “Present”. Those not on the line when their names were called needed to be accounted-for. Guard duty, recent return from guard duty, other duties, confinement to bed (in the hospital or tent) due to illness or injury, or on leave of absence (a.k.a. "on leave") were all considered excusable absences. Those NCO’s with knowledge of such absences answered for the troops not present. Otherwise, the missing men were considered absent without leave (permission). In these cases, fellow friendly troops often answered for those who departed, thus covering their absences until they returned.

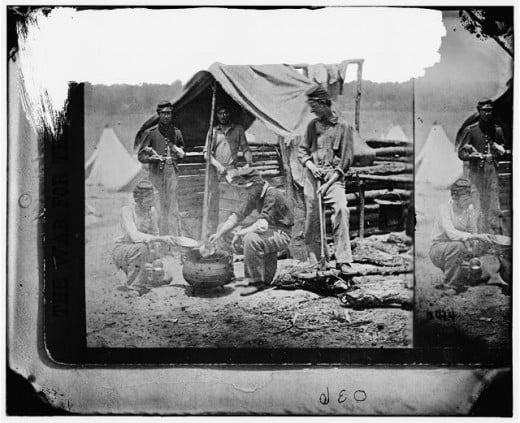

Once the Roll was taken, the First Sergeant reported the results to the Company’s commanding officer. At that time, announcements, if any, were made by the commander. Afterward, the Company was dismissed, the men fell-out of the line, and the duties of the day began. Men were detailed to gather firewood and stoke cooking fires, or to retrieve water, or whatever else was deemed immediately necessary. The remainder used the time to respond to nature’s call or even to take post-Roll Call naps if possible.

The next call was the Breakfast Call, which was at or about 7:00 am (0700). This was the first meal of the day for the troops. They dug into their haversacks and cooked, or ate cold, their morning repasts from their rations or whatever else was acquired outside of regular issuances (foraged food). Breakfast, unless other priorities interfered, lasted approximately an hour, which included the time to clean afterward.

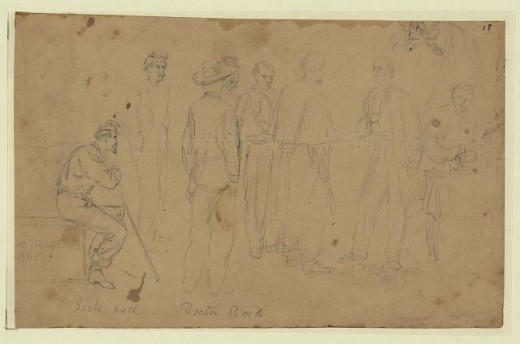

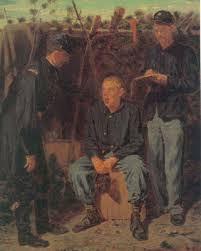

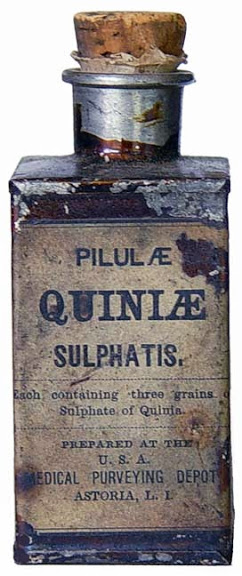

After Breakfast came the Sick Call at approximately 8:00 am (0800). This was the opportunity for those sick or injured to visit the Regimental Surgeon. Any number of healthy troops also responded to this call in attempts to avoid duty. The men who responded to this call came forward and assembled about the First Sergeant, who then led them to the Surgeon’s shelter or tent. One at a time, the Surgeon saw the patients and, if possible, diagnosed what was the ailment. One of his assistants – usually little more than a Hospital Steward – recorded the needed information, such as the soldier’s name, Company, ailment, and prescribed treatment. The Surgeon often prescribed quinine, a powerful drug that was used for ailments ranging from stomach and bowel ills, to toothaches, headaches, fevers, and injuries. It was specifically manufactured to combat malaria but, obviously, other uses were found for it as well.

Those troops that were legitimately ill and needed regular care, and those that faked illness really well, were assigned to the camp’s hospital where various treatments were attempted. Others received prescriptions such as light duty only, or bed rest confined to the soldier’s tent. Of course, if the soldier was found to be healthy, he was ordered to immediately return to his Company and report for regular duty.

Troops not responding to Sick Call were expected to remain healthy through to the next day’s Sick Call. Of course, in special cases such as wounds by enemy fire or accidents, troops were allowed and required to visit the Regimental Surgeon independent of a Sick Call.

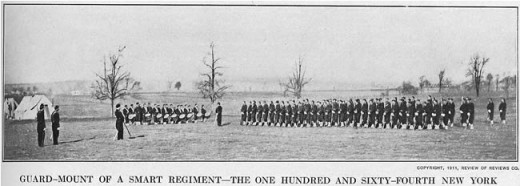

At roughly the same time as Sick Call, the first day’s Guard Mounting began. Guard Mounting was the exercise to provide security for the camp. It consisted of three “reliefs”, each eight hours long, which thus constituted 24 hours each day. The First Relief was from 8:00 am (0800) to 4:00 pm (1600). Men from each Company, detailed for a “relief”, assembled under the Officer and NCO’s in charge and set-off for their assigned areas. The Guards stood two-hour shifts and then were “off” the remaining six hours. They were still on Guard Mounting duty, however, and were nearby in order to support the standing Guard if needed. Troops that served as Guardsmen were positioned on the outskirts of the camp or well beyond it, and they were required to keep watch for any unusual activity. This watchfulness included the need to catch any man from the camp that sought to escape.

The Guards patrolled assigned distance intervals dependent on terrain, numbers of Guards, and area to be guarded. If they were fortunate in the terrain in which they were deployed, Guards took advantage of natural cover. If not, they were expected to remain just as steady and vigilant out in the open.

Guards were the first line of defense in case of enemy attack and, as a result, the first targets for hostile fire. As a result, regardless of how far or near to the camp was the enemy, Guards needed to be battle-ready, fully armed, and equipped. They were expected to not let their weapons touch the ground, and to remain perfectly awake and alert to the goings-on.

At the end of each shift, the next detail of men approached, led by the officer and/or NCO in charge, and the Guard at each post was relieved. The relieved Guards, again led by the officer and/or NCO in charge, returned to the station and to the remainder of the Guards of that “relief”. They were otherwise excused from any of the day’s duties in the camp proper as well as excused from the need to stand at a post.

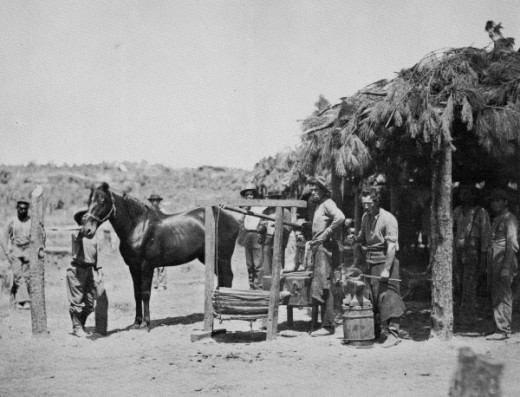

For those not responding to Sick Call or Guard Mounting, the next call was the Fatigue Call. This was the call to the labors necessary to maintain the force in camp, and no soldier was immune to this call. Labors ranged from cleaning and maintaining (a.k.a. “policing”) the campgrounds, to going out on wood-cutting details, to burying dead horses or men, to building roads, to digging latrines, to hauling water, etc. There was literally no end to the duties a soldier was assigned. Those whose fatigue duties were not within the immediate vicinity of the Company campground assembled under an NCO-in-charge, then marched off to the work site.

The next call, after morning Fatigue duty, was the morning’s Drill Call, which sounded anywhere from 10:00 am (1000) to 11:00 am (1100).

If a soldier was lucky (though he never admitted this), he was drilled often and competently in the close-order linear formations in which soldiers of the day fought. These linear formations were fairly complicated and required a good deal of concentration and attention to detail. This was no easy task when enemy fire scythed through the ranks and when orders were not heard through the din of battle. As a result, the importance of drill was not lost on the officers, even the many who were as new to it as the soldiers themselves. Drill was universally disliked, but it was a very necessary evil in order to properly build a military force of reckoning.

The morning drills were often Company-sized, required full uniform, all accoutrements, and weaponry, and took place in the drill grounds of the camp. As with most calls to suit up in full gear, there were preparatory calls made by the NCO’s a few minutes before the allotted time. This was done to inform the Company that they needed to get ready – ie. “first call for drill… 2nd call for drill…” At the appointed time, the Company NCO’s announced “Fall-In” to the Company, and the men came onto the line with all the needed clothing and equipment. Once the Company was properly formed, it was led to the drill grounds. The drills lasted as long as two hours. In cases of inclement weather, such drills might have been called-off, but there was no guarantee of that.

At 12 noon (1200), the Dinner Call sounded. Troops, after fatigue and drill duty in the morning, often worked up hearty appetites for their second meal of the day. Similar to the Breakfast Call, Dinner was cooked, or eaten cold, out of issued rations or of other acquired food, and lasted an hour or more in length.

After Dinner, at approximately 1:00 pm (1300), came another Drill Call. This call often involved the larger Regiment formations, or possibly Brigades or Divisions. These drills again necessitated full uniform, accoutrements, weaponry, etc. This type of drill usually lasted approximately two hours.

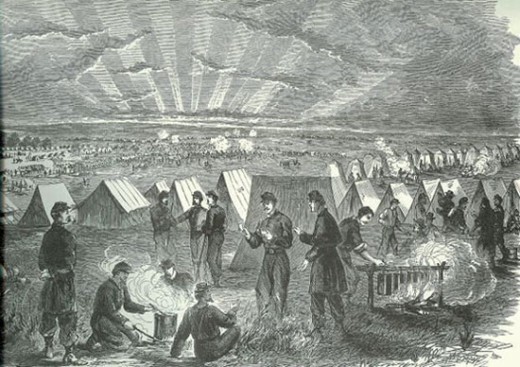

In some rare cases, officers in the higher echelons took this time to stage mock battles that included the large Brigade and/or Division formations. They sometimes included other arms – Artillery and/or Cavalry – in order to more fully prepare the officers and men for actual battle conditions. The ammunition used was blank cartridges, but the noise and smoke levels were the same as in actual battle. Drilling in larger formations tended to make the Brigades and Divisions fight more cohesively and effectively on the actual battlefield. Unfortunately, most drills were limited to Company and Battalion drills, leading to more disjointed action in the larger formations.

More Fatigue Duty was usually the call, after the Battalion Drill, at about 3:00 pm (1500) or so. There was always more firewood and water to gather or other minutiae to perform when not called to drill.

The next “relief” for Guard Mounting assembled at 4:00 pm (1600) and set-off with officer and NCO’s in charge to relieve the prior shift’s “relief”. Those relieved Guardsmen, along with officer and NCO’s, then returned to the camp proper. Their day was mostly complete.

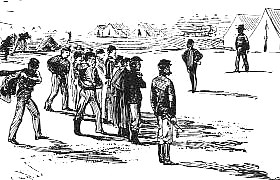

At about 5:45 pm (1745), the Retreat Call sounded, which indicated the end of the soldier’s day and a general retirement from duty. Companies then gathered to respond to the second Roll Call of the day. Soon after that, a Battalion Dress Parade was held. Companies assembled and marched out to the parade grounds to align as the Battalion. Uniformity of dress, including uniform, accoutrements, and weaponry, was generally required. At this time, the commanding officer usually read general orders (expectations of duty, courts-martial or possibly military campaign results) and criticized the unit’s performance and conduct if deemed necessary. When dismissed, the Companies marched back to their assigned camp areas and then, unless further comments by Company commanders were warranted, the troops were summarily dismissed.

The evening meal, or Supper, was the next order of business at about 6:30 pm (1830), though there was no official call for it and it had no specific length of time. As with Breakfast and Dinner, the men cooked and/or dined cold on their rations or whatever else on which they laid their hands.

At about 8:30 pm (2030) came the bugle call Tattoo along with the need to line up for the evening Roll Call, the third and last of the day.

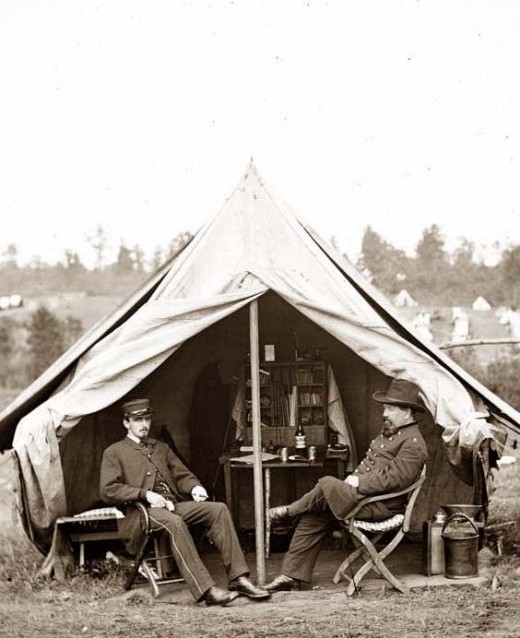

At 9:00 pm (2100) came the bugle call Taps, which was the order for “lights out”. All candles, lanterns, and fires needed to be extinguished, though fires were often stoked to embers for easier re-ignition the next morning or for a small degree of warmth during cooler weather. All noise-making also needed to cease and the men, not inclusive of the Guards, were expected to be in their quarters to sleep. It is interesting to note that officers, especially the young ones, did not often follow this procedure for themselves. They often chose, instead, to congregate with each other, make more noise, and stay up later, than was probably advisable.

At midnight (0000) came the third and last “relief” for Guard Mounting. NCO’s shook the assigned men awake, with varied degrees of success, and they all assembled under the officer in charge. They then set out to relieve the second “relief”, which came back to camp and settled down for the remainder of the night. Depending on the situation, these recently-returned Guards might have been allowed to stay in bed for a while, beyond the next morning’s Reveille. This was in order for the men to get as much sleep as their other comrades in camp but, again, there were no guarantees of that!

And the next day was probably more of the same described routines.

It was through Army Regulations that the soldier began to learn his craft.

He needed to learn how to maintain his weapons: how to dismantle and/or clean and protect them, and how to make them ready for immediate usage.

He needed to learn to properly wear and maintain his uniform: how to position and adjust the uniform on the body, how to clean and protect the uniform, and know what clothing he can and can’t wear by Regulations.

He needed to learn to properly wear and maintain his accoutrements: how to position and adjust them on his body, and how to dismantle and/or clean and protect them.

All, or most, of these topics were covered in the Regulations for the Army of the United States publications (1857 and 1861 primarily). It is unknown if any common soldiers other than officers had access to these publications or, if so, whether they bothered to read the publications. In all probability, the troops received the equivalent of On The Job Training, where help from veteran comrades (if any existed in the Companies), trial-and-error, and the concomitant feedback from officers and NCO’s, informed them of whether or not they followed Regulations in their attire, equipment, and actions.

It was through drill that the soldier perfected his craft.

Every soldier needed to learn how to operate his weaponry: how to carry and position the firearm in various ways. He needed to learn the several steps on how to load ammunition into the firearm, and how to aim and fire the firearm. He needed to learn to how to affix the bayonet onto the firearm, maneuver the firearm with the fixed bayonet, and use the weapon in close quarters combat.

He needed to learn how to maneuver and fight in close-order linear formation. He needed to know his place in the alignment as well as the places of his comrades.

Above all else, he needed to learn to follow the commands of his officers.

As was mentioned in the Day in Camp section, drill occurred at least twice per day: Company-sized drill in the morning, and Battalion-sized drill in the afternoon. Also mentioned, more drill might have been required, on a regular or varied basis. These extra drills might have involved larger units, such as Brigades or perhaps even Divisions.

For the men in the ranks, help - or a necessary form of jostling - to learn the many different movements (often called “evolutions”) in linear maneuvers came from the NCO’s behind the lines – thus revealing why they are called “file closers” – and adjacent comrades. Sometimes officers would help too, if they were not too busy yelling instead.

Afterword

The next article on this topic is called American Civil War Life: Union Infantryman - Life in Camp VI; An Army Moves On Its Stomach: The Rations.