- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era»

- Twentieth Century History

America's Internment Camp Duirng W.W.II - Japanese-American Experience

America's Internment Camp - Japanese-American Experience

Discussion on the Japanese-American Experience During World War II

By Michael Mikio Nakade

(An Imaginary Scene: History teacher’s friend, Mr. Sam Kai, visits the classroom and fields questions from students. Mr. Kai spent almost four years in the internment camp in Utah during World War II.)

History Teacher: Today, we’re honored to have a special guest to our classroom. Boys and girls, this is Mr. Sam Kai from San Francisco. He was 25years-old when the Empire of Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941. As a result, he spent almost four years in an internment camp in Utah. Later in his life, he was involved in a campaign for redress and reparation movement. His and many other people’s persistent efforts paid off in 1988 when President Reagan signed the bill into the law, providing $20,000 to each survivor of the internment camp during World War II with an official apology from the United States Government. Without further do, let’s have students ask Mr. Kai questions.

Student 1: Mr. Kai, what was it like on the day Japan attacked America?

Mr. Kai: I was living in San Francisco. It was 9 a.m. in California. The news reached me by 10 a.m. I already felt that we, the Japanese-Americans living in California, would be in big trouble.

Student 2: Like how? Did Americans physically attack you on the day Pearl Harbor was bombed?

Mr. Kai: No, nothing like that. It was a ‘feeling’ in the air. I grew up in San Francisco and had many friends who weren’t Japanese. My Chinese friends began wearing a little sign that said, “I’m Chinese.” My Caucasian friends were no longer friendly to me right after December 7. None of them openly accused me for the Pearl Harbor attack, but they were no longer comfortable being my friend. It was devastating, psychologically.

Student 3: You were born and raised in America, right? So, you rooted for America during the war, correct?

Mr. Kai: Yes, it was given. I grew up speaking Japanese at home because my parents didn’t speak much English. They had difficulty understanding that their old home country attacked their new home country. It was hard for them. But, for my generation, the Nisei or the second generation, we received a public school education in America and were fully American in our loyalty. It was painful to have my non-Japanese friends doubt my allegiance to America.

Student 4: What was it like going to the internment camp? Was it as bad as the Nazi concentration camp?

Mr. Kai: As far as I know, there was no gas chamber to kill us at our camp. I was basically locked up as a prisoner in the Utah desert. But the comparison is irrelevant, though. The Nazi persecuted the Jews because of their racist ideology. The U.S. government locked the Japanese-Americans up even though most of us were American citizens. Our rights as American citizens were completely denied because we looked like our enemies. It was out of hysteria that Gen. DeWitt declared that the Japanese-Americans would pose a security threat to the United States. It was a bogus claim, but many Americans wanted to believe this B.S.

Student 5: It’s hard to imagine that the U.S. government could just relocate you folks. There must have been lots of hard feelings back then. How did you feel when you were leaving your home and checking into a camp in a desert somewhere?

Mr. Kai: You know, we didn’t really go out there and resist. For the most part, we resigned and went along. When FDR signed the Executive Order 9066, we were given one week to sell our possessions and move to the relocation camp. We were allowed one suitcase each. There were about 100,000 Japanese-Americans on the west coast. You can imagine there were lots of garage sales. My family and I sold what we could. We then asked our really good friends to watch out for our house while we were gone. The only trouble was that we had no idea when we could come back. That feeling of uncertainty was the toughest part. We were gone for three and an half years. It was the longest three and an half years of my life.

Student 6: You said you really didn’t resist the order by the government to relocate. Why not? Didn’t you feel like fighting against this injustice?

Mr. Kai: Well, we resigned to our fate. Many of us thought that it would be in our best interest to accept the government’s order so that we would be accepted by the rest of the country later on. Plus, there was the Japanese attitude of ‘this cannot be helped,’ we said, “shikataganai.’ We kind of accepted America’s anger against Japan for the Pearl Harbor attack, knowing that we were the perfect scapegoats. But, I must tell you that three young American born Japanese men sued the government for the relocation. They fought. So, not all Japanese was accepting of this injustice, willingly.

Student 7: Yeah, I heard about one

of the lawsuits reaching the Supreme Court eventually. What do you think of that?

Mr. Kai: Interesting that you ask. The case is known as Korematsu v. United States. Mr. Fred Korematsu disobeyed the order and didn’t report to the internment camp. He had a Caucasian girlfriend at that time and refused to leave his Oakland, California neighborhood. A very courageous man. But, he was soon arrested and was convicted. He kept appealing the court’s decision, and the case reached the Supreme Court in 1944. The Court sided with the government. Mr. Korematsu ended up in an internment camp as a form of his punishment. He lost the case, and it didn’t surprise me. After all, America was fighting the Empire of Japan. Most Americans couldn’t tell a difference between Japan’s Japanese and America’s Japanese. As far as my feeling for Mr. Korematsu goes, I just thought that he had a lot of guts in suing the government. I respected him for that. But, many Japanese-Americans in my camp wished that Mr. Korematsu would just shut up. They felt uncomfortable that one of them was suing the government of the United States. Now, this feeling changed after the war. Today, Mr. Korematsu and two other men who sued the government were very well respected.

Student 8: What was it like when you came out of the camp?

Mr. Kai: Honestly, I was both glad and scared. Glad because I could be free again. You have no idea how precious freedom is until it is taken away from you. I didn’t have my freedom for so long. But, I was scared for my life. I didn’t know how the rest of America would treat my family and me. Luckily, my neighbor in San Francisco took good care of my family home. We could settle back in. It wasn’t as bad as I thought it might be.

Student 9: Will you tell us about the redress and reparations? When did you begin this campaign?

Mr. Kai: The momentum for asking the U.S. Government’s apology for their mistake became very strong in early 1970s. My children’s generation is called Sansei or the third generation. They were becoming young adults. With the Vietnam War protests going on, they felt empowered to protest the past wrong of the U.S. Government. My generation was much gun-shy about lodging the complaints. I guess we were docile, quiet, and obedient Japanese-Americans, and that’s how we were raised. But, the younger generation was different. They were ready to stand up and shout against the government. I decided to join the cause because I got angrier and angrier as I got older regarding my internment experience. In other words, the sense of resignation at the time of Executive Order 9066 went away.

Student 10: But, the official apology didn’t come until 1988. What took so long?

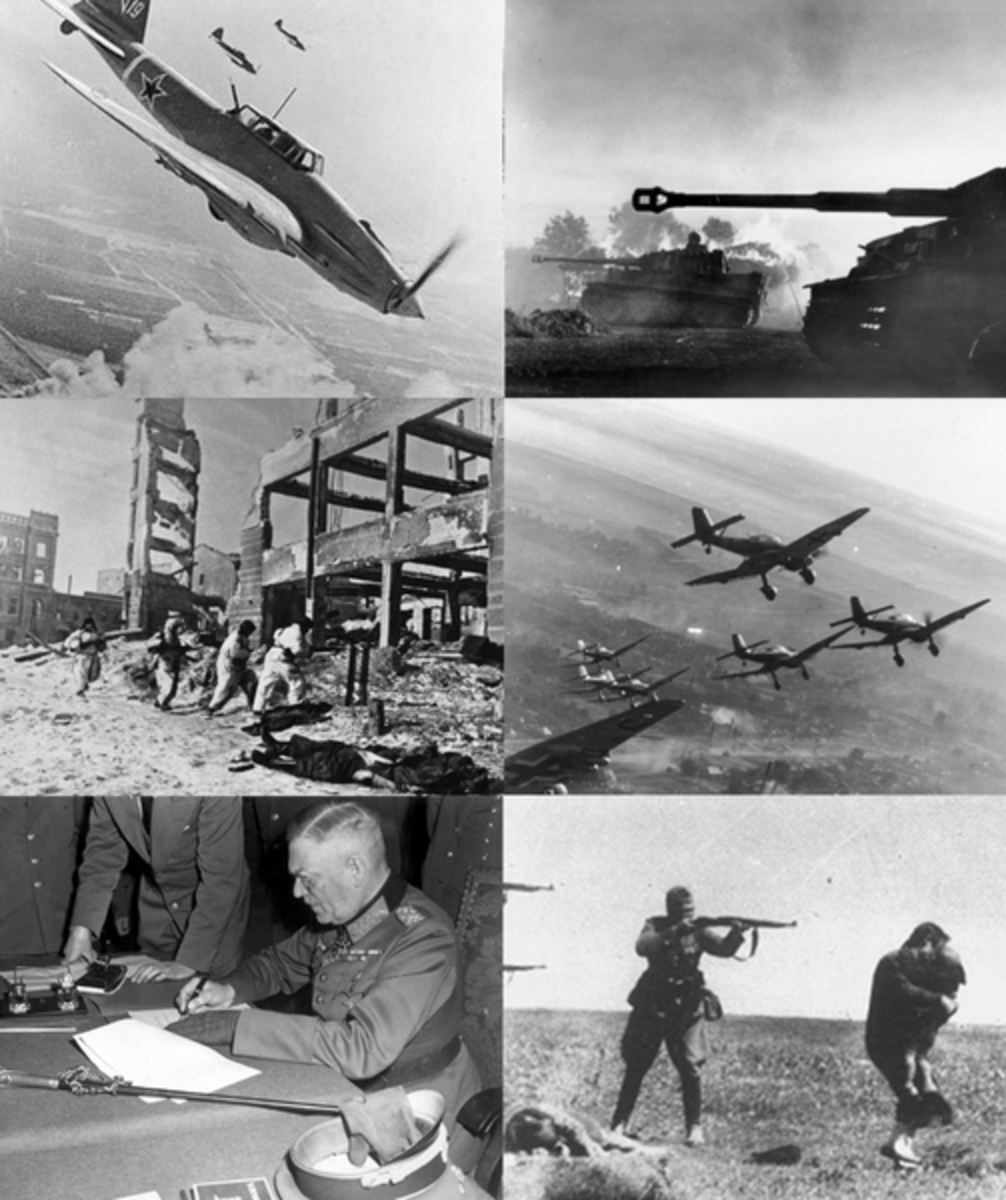

Mr. Kai: Oh, it’s the red tape. Many congressmen felt no need to apologize to the Japanese-Americans since it was Japan that started the war. It really showed that they still didn’t know that Japan and the Japanese-Americans were two different things. Anyway, we needed strong and capable politicians at the Capitol Hill to get this thing moving. I honestly think that two senators from Hawaii really helped. They were former soldiers for the United States Army during the War and were famous for their bravery. Having them push for the redress and reparation was very effective. Someday, you folks will read about the brave Japanese-American soldiers who fought in the European theater of World War II. They risked their lives to prove their loyalty to the Stars and Stripes. Many died in the action. With their heroic war records, no one would dare question our loyalty to the United States. One senator from Hawaii lost his right arm in the battle. His name is Dan Inoue. He is a real hero.

Student 11: What about the Korematsu guy? Was he vindicated later on?

Mr. Kai: Glad that you mentioned Mr. Korematsu. I met him in person in the 1970s, and we worked together for the redress issue. He and two other Japanese-American men were all declared innocent later on. I was actually at the courthouse in San Francisco in 1983 when the judge agreed to remove the criminal record from Mr. Korematsu’s record. It was a sweet moment. We all cried.

Student 12: That’s interesting. How did this 180-degree change come about?

Mr. Kai: It was due to the efforts of one Law professor from the University of California at San Diego. His name is Peter Irons. He researched the Korematsu v. United States case in the 1970s and went over lots of records that were packed inside cardboard boxes. Then, one day he discovered a memo that said the Japanese-Americans on the west coast would not present any military danger to the security of the United States. That memo was addressed to the Solicitor General. With that, Professor Irons thought that he could help overturn Mr. Korematsu’s conviction. He and his assistants successfully argued that the Solicitor General in 1944 lied about this memo and kept repeating General DeWitt’s insistence that the Japanese-Americans had to be relocated for a security reason. It was a groundless, grotesque, and complete lie. But, people at that time wanted to believe this lie, including the majority of the Supreme Court justices because it came from the Solicitor General.

Student 13: Did anyone punish this Solicitor General?

Mr. Kai: Yes. Although he was dead by 1983, he was still reprimanded, posthumously.

Student 14: How did you feel when you heard that the apology was coming to your way along with the redress check?

Mr. Kai: A sense of vindication all the way. We worked so hard for so long for that moment. I lost three and half years of my life during the prime of my life. Can you imagine that you will spend the next 3 plus years in a locked up facility somewhere unsavory? The reason given to you is a complete bogus, on top of that, by the way. I hope and pray that the American government will never again make this kind of mistake. Internees who were still alive in 1988 received $20,000 as a redress. I was happy and felt proud to be American. My respect for the American government was restored.

History Teacher: Thank you, Mr. Kai for your candid answers to my students’ questions. It is wonderful to hear from the one who went through actual historical incidents. At the moment, I am very disturbed by the action of the Solicitor General back in 1944. He actually lied in the Supreme Court in order to justify the unnecessary relocation of 100,000 Japanese-Americans on the west coast. That is difficult to swallow. At the same time, I have a tremendous respect for the law professor from San Diego. He dug the truth from a pile of paper and restored the justice. I’m happy that those three Japanese-American men were later declared innocent of all charges. That’s sweet.

(This work depended on two sources: 1) The Teaching Company’s Lecture Series, The History of the Supreme Court, Lecture 18, “Pearl Harbor and Panic” by Prof. Peter Irons, and 2) an actual interview of Mr. Sam Kai by the author himself in San Francisco in April 1996.)