Duccio di Buoninsegna and the History of the Maesta

Maesta means majesty in Italian, and Duccio di Buoninsegna’s altarpiece which is more famously known as Duccio De Maesta, or the Maesta of Duccio is very aptly named.

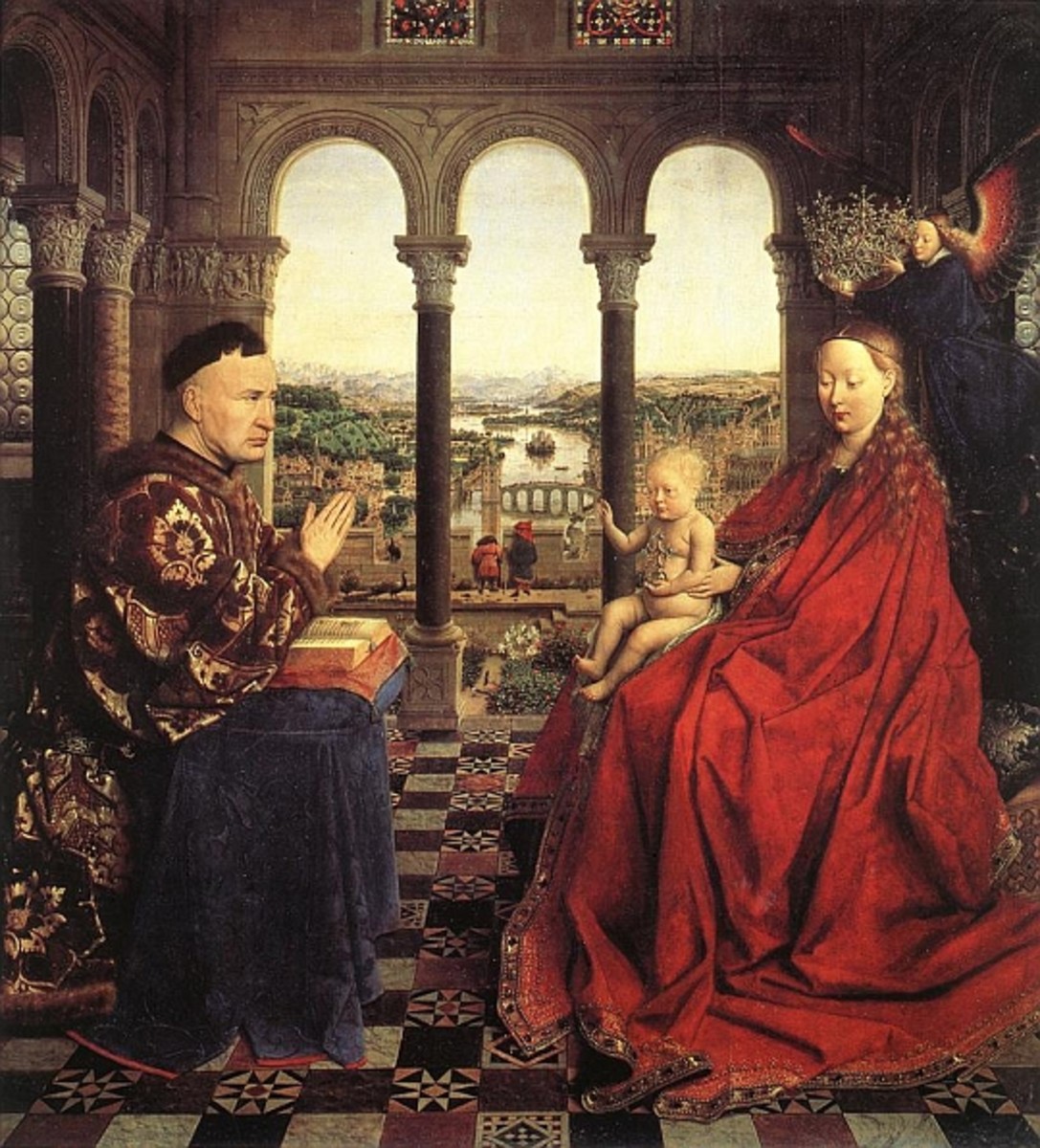

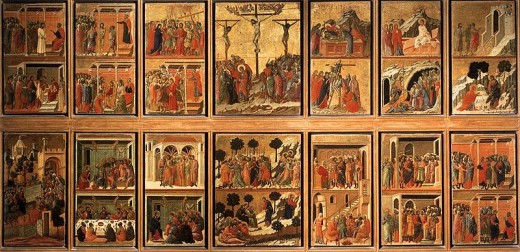

Completed in 1311, altarpieces during this time were generally painted panels of wood that were placed on the wall behind the altar in Italian cathedrals and churches. These altarpieces were often commissioned by religious leaders of the best Italian painters of the time and displayed religious scenes and stories that were easily recognizable to the congregation.

According to The Oxford Dictionary of Art, Duccio di Buoninsegna was believed to be the best painter at the Sienese school in Siena, Italy, and the Maesta, his most well-known work, was a double sided panel of immense craftsmanship.

The Oxford Dictionary of Art describes the entire front side of the fifteen foot high piece as an image of the Virgin Mary portrayed as the Queen of Heaven while holding the Christ child on display to a “court of saints and angels.” The four patron saints in Siena at the time are recognizable and join the heavenly hosts in paying supplication to the Virgin Mary (Carli).

The Altarpiece reflected the religious focuses of fourteenth century Italy at the time and told the story of Christ’s life in images similar to many altarpieces. However, the size, images and design of Duccio’s Maesta were unparalleled in Italy at the time, and set a precedent for many altarpieces in the future.

Duccio's Timeline

- 1278- First Commission

- 1308- Maesta Commission

- 1309- Reverse side of the Maesta Commissioned

- 1311- Altarpiece Completed

- 1319- Believed Death of Duccio

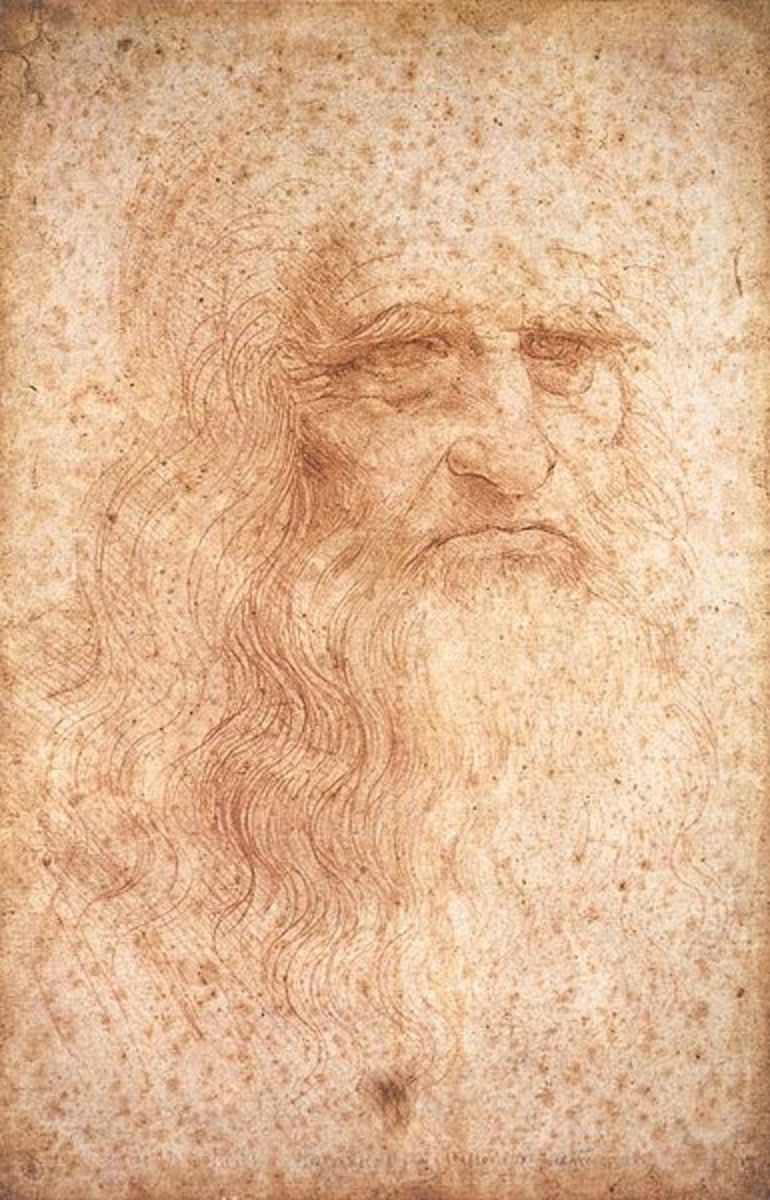

Life of Duccio di Buoninsegna

Duccio’s beginnings are mysterious; almost nothing is known of his life before his first commission in 1278, when he was paid a small sum to paint coffers. Much of his early work was commissioned book covers and smaller panels for churches.

On October 9, 1308, a contract was recorded between Duccio and church officials stating the terms of a large commission. Duccio was to paint an altarpiece for the Siena Cathedral; he was not to work on anything else until the piece was done, he was to work continuously on it, and he was not to accept any help in painting it (Gordan).

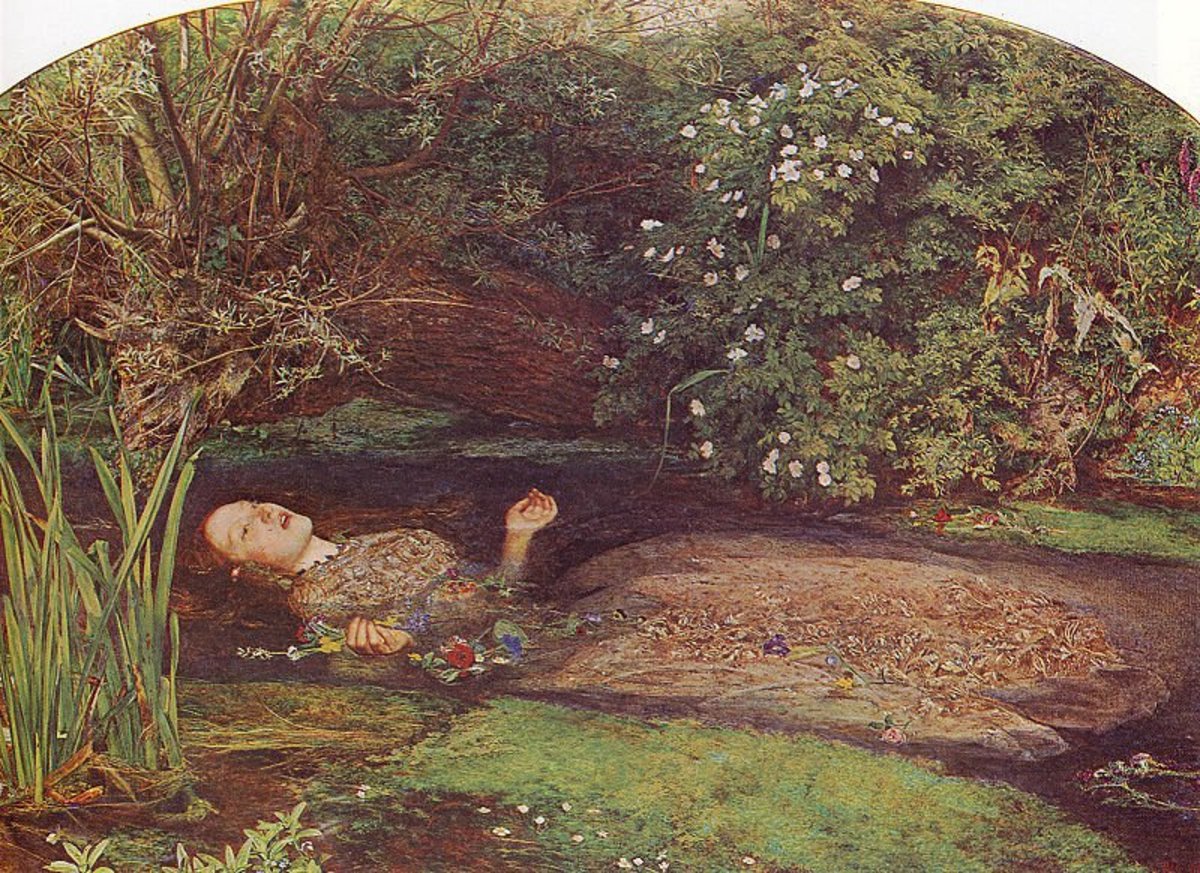

A document dated a year later in 1309 contained the terms of agreement for the reverse side of the altarpiece. Duccio was commissioned to paint thirty three separate stories of the Passion (suffering) of Christ on the back, and would be paid ninety five florins in total for the work.

On June 9th, 1311, the altarpiece was completed and was paraded through the streets before it was then placed behind the altar of the Siena Cathedral until its removal in 1506 (Gordan).

What was the Maesta Based On?

The Maesta was an expansive undertaking that gathered inspiration from many different types of religious artwork at the time. Much of it what was included on the Maesta was revolutionary, but Duccio likely also drew from many sources during the time period, most notably frescoes completed by Giotta, a friend and possibly one of Duccio’s instructors (Stubblebine 176).

Newly renovated frescoes in Old St. Peter’s Basilica during the thirteenth century may also have influenced Duccio’s images of the Passion of Christ- indeed, there is evidence that Duccio may have made a trip to Rome in in the 1290’s to gather inspiration at many ancient art sites (Stubblebine 177).

However Old St. Peter’s may have provided Duccio with the greatest inspiration for his many-paneled tale of Christ’s life. The twenty two frescoes in St. Peter’s basilica telling the story of Christ’s life between his baptism and resurrection were among the longest narratives in Italy at the time, and the unusually large section devoted to Christ’s crucifixion in the basilica is reflected in Duccio’s double sized crucifixion scene (Stubblebine 177).

What Happened to the Maesta?

The whereabouts of the Maesta after its removal in 1506 are not recorded until August of 1771, when the Maesta was sawed into two pieces, separating the front panel entitled Virgin and Child Enthroned from the Passion of Christ on the reverse.

In this process, the Maesta was also cut into several vertical pieces and some of the images- including the face of the Virgin Mary- were extensively damaged (Cooper 155). Pieces of the massive altarpiece vanished as a result, sold to private collectors, cathedrals and museums. Some were stolen, and remain missing to this day.

A 1965 restoration was only able to partially restore the panels and remaining paintings, but historians struggled as they were unable to differentiate between organization of the panel pieces based on iconography or on geometric shapes (Cooper 160).

The Remaining pieces are divided among museums and the Siena Cathedral. In 2004, the Metropolitan Museum of Art gained the Madonna and Child section of the Maesta (Christiansen 4).

Definitions

Buttressing- Increase the strength of or justification for; reinforce.

Predella- Supportive platform an altarpiece stands on.

Buttressing on the Maesta- What Made the Maesta so Important

While the tempera artwork on the altarpiece may have been relatively conventional, the architecture of the piece itself was revolutionary. Painted on durable poplar wood, the Maesta featured a predella, a relatively new design that constituted the base of an altarpiece painted with further religious imagery (Sullivan 597).

According to Christa Gardner von Teuffel, an expert on Italian altarpieces, Duccio most likely created the innovative buttressed polyptych for the Maesta (von Teuffel 135). The buttressing on the Maesta would have been in place to provide stability and architectural support to Duccio’s polyptych that also featured the newly designed multi-story altarpiece (von Teuffel 134).

The heavy wood and large frame of the Maesta would have required the support of buttressing in order to stand and Duccio’s new innovations in fourteenth century altarpieces were replicated long after in many other religious paints and iconography.

The buttresses had a dual nature, revealing Duccio’s genius and masterful artwork. Not only did they provide support for the free-standing altarpiece so that it could be seen from both sides without iron bards holding it up, but they were likely covered with the same design as on the Virgin’s throne (von Teuffel 38).

Replicating the same pattern may have provided a necessary visual appeal to the viewer, but it could have also conveyed a symbolic meaning; the buttressing supported the altarpiece and the Virgin’s throne supported Christ’s and the Virgin’s divinity.

Legacy of The Maesta

Duccio’s altarpiece was hailed as an instant masterpiece, carried from his workshop on the day it was completed and heralded with several days of feasting and an unusual show of generosity to the poor.

Duccio recognized his success and signed his single greatest work with a flourish:

“Holy Mother of God, grant peace to Siena, and life to Duccio because he has painted you thus” (Carli).

Despite his payment for the newly completed Maesta, Duccio apparently ended up in debt just two years later in 1313 and was believed to have died by 1319- just eight years after the completion of his most notable work (Carli).

He was survived by his wife, seven children and numerous students who went on to produce other great works of art. However, Duccio’s greatest legacy lies in the Maesta. In total, the fifty nine classically painted images speak volumes of the importance the Italians placed on Christ and his mother, and portray the classical style of painting used in narratives at the time.

The architectural feats that Duccio invented and used in the Maesta brought to life countless altarpieces in the coming centuries and made freestanding, double-sided altarpieces possible for many Italian cathedrals.

The faces of the Virgin mother and her divine child watched over their followers from above the Siena Cathedral’s altar for many years, and still watch over them today.

Sources

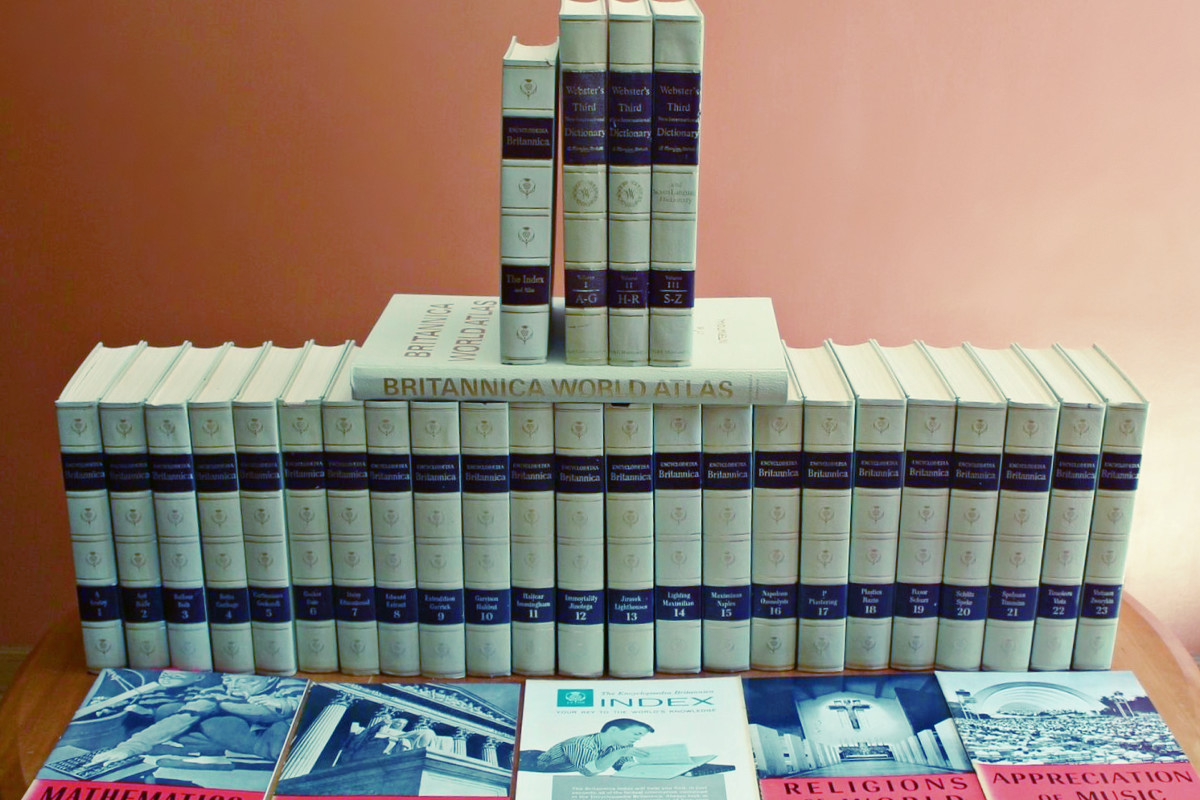

Carli, Enzo. "Duccio." Britannica Academic Edition. Encyclopedia Britannica. Web. 24 Mar. 2012. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/172850/Duccio>.

Chilvers, Ian. "Duccio Di Buoninsegna." The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 20 Mar. 2012. <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t2.e1115>.

Christiansen, Keith. Duccio and the Origins of Western Painting. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008. Print.

Cooper, Frederick A. "A Reconstruction of Duccio's Maesta." The Art Bulletin 47.2 (1965): 155-71. Print.

Gardner, Von Teuffel, Christa. From Duccio's Maestà to Raphael's Transfiguration: Italian Altarpieces and Their Settings. London: Pindar, 2005. Print.

Gordon, Dillian. "Duccio (di Buoninsegna)." Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 19 Mar. 2012. <http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T023857?q=Duccio+De+Maesta&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit>.

"Madonna (religious Art)." Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica. Web. 20 Mar. 2012. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/355920/Madonna?anchor=ref279484>.

Stubblebine, James H. "Byzantine Sources for the Iconography of Duccio's Maesta." The Art Bulletin 57.2 (1975): 176-85. Print.

Sullivan, Ruth W. "Some Old Testament Themes on the Front Predella of Duccio's Maesta." The Art Bulletin 68.4 (1986): 597-609. Print.

Turner, Jane. Encyclopedia of Italian Renaissance & Mannerist Art. New York: Grove's Dictionaries, 2000. Print.

Von Teuffel, Christa G. "The Buttressed Altarpiece: A Forgotten Aspect of Tuscan Fourteenth Century Altarpiece Design." Jahrbuch Der Berliner Museen 21 (1979): 21-65. Print.