England Invaded (4): Chess Board

By Nils visser

So far we’ve looked at the various characters involved in the First Baron’s War, both on the “French” side and on the Anglo-Norman side. We discovered that things are rarely as clear cut as we would like them to be. For the supposed “French” side included a good number of parties from England, at one point two thirds of English nobles declared support for Prince Louis, and the royalist party, as we started to call the Anglo-Norman team representing respectively King John I and King Henry III, were facing a defeat.

Moreover, in trying to approach the whole thing from a moviemaker’s perspective, it was nigh impossible to achieve a satisfactory division between good guys and bad guys. After all, King John I of England, the initial leader of the Anglo-Norman party, tentatively identified as the good side, was a nasty piece of work. The leader of the bad side, Prince Louis, had potential as a good guy, if we are willing to overlook his later mass homicidal tendencies that is. His wife, Blanche of Castille, would make a perfect heroine, she has all the trappings of a good guy and a heart in the right place. In contrast, the good side features some perfectly horrible chaps, we highlighted one of them but did mention that he often worked in conjunction with folks of a supposedly superior social and moral level as well, such as a number of Earls. On the other hand, the good side also has characters like William Marshal, Nicola de la Haye, Hubert de Burgh and William of Cassingham, the stuff that legends are made of, or ought to be, one of our aims was to figure out why folks like these haven’t become household names.

THE SETTING

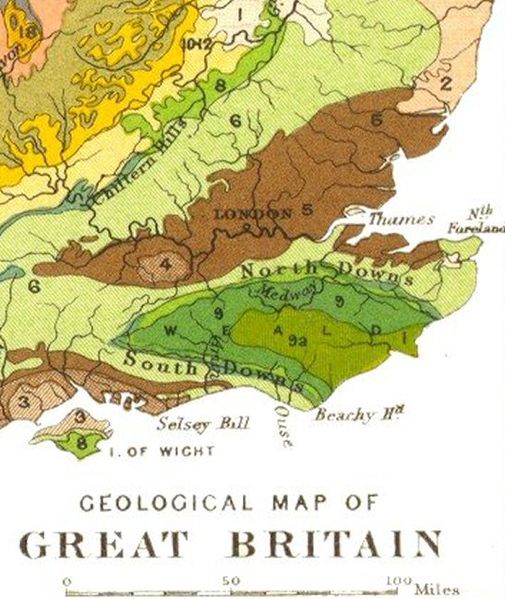

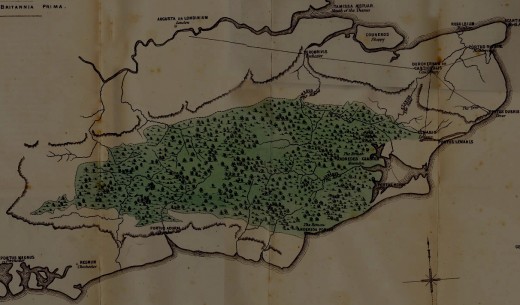

Most of the action takes place in South-eastern England, Anglia and the Midlands. As already mentioned, ere the French came the baron’s initial revolt was symbolized by their seizure of Rochester Castle, a strategically important place between Dover and Canterbury (seat of the Archbishop of Canterbury) on the one hand, and London on the other.

If you’re unfamiliar with the layout of the land, the importance of Rochester may be somewhat puzzling. Imagine for a moment that the island of Britain has a big toe sticking out eastwards, pointing at the European continent as it were. Now draw a diagonal line across this toe, the upper part starting at the junction between toe and foot (London) and then running downwards to the bottom of the tip of the toe (Dover and Folkestone). The upper half of the big toe is the County of Kent, the lower half consists of the current Counties of West Sussex, East Sussex and Surrey, which I’ll conveniently lump together as “Sussex”. Both Kent and Sussex have a spine in the form of a series of ridges running from east to west. The spine in Kent is called the North Downs, the spine in Sussex the South Downs. The broad expanse of land between the North and South Downs is known as The Weald, and in the thirteenth century this area was heavily wooded. The Weald ran all the way from the beginning of the North Downs in eastern Kent towards the vicinity of Winchester and didn’t offer an easy north-south passage, especially if it were to be contested, as we shall find out. That meant that the route from Dover to London was bound to a corridor running along the north of Kent. Rochester Castle stood astride the middle of this corridor, overlooking the bridge crossing the Medway river which forms a natural boundary at this point. Once past London, one could skirt the north-western fringe of the Weald and reach the old capital city of Winchester, from whence Portsmouth and Southampton were within reach.

This is one reason that Prince Louis felt reasonably secure when he held Canterbury, Rochester, London and Winchester. In his mind he had a firm grasp on the major places in the south. What he didn’t comprehend, and what his father did, was the importance of castles. King Philip Augustus of France , when told Dover had not yet been captured by Louis, reportedly said: “Then he has not taken one foot of English land”.

Not only did Dover Castle occupy a strategic place, but castles also played a very important part in warfare, as all parties concerned should have learnt during the conflict between Philip Augustus and respectively King Richard I and King John I in Normandy.

One of the essential parts of war back then, as it is today, was surprise. One of the key ingredients of surprise is speed. If a field army could move rapidly enough, it was usually able to surprise the foe and thus win easy victories. John put this into effect at Mirebeau Castle, when he was able to capture Prince Arthur and the entire rebel leadership who didn’t anticipate the speed with which John would march to the relief of the castle.

Well defended castles could severely hamper the ability of a field army to conduct such manoeuvres. For if a field army were to ignore a well-garrisoned castle and pass it by, its supply routes were exposed, and it also risked several garrisons moving out of the castles to form an enemy field army that threatened the rear. Therefore, wisdom dictated that enemy castles needed to be reduced before an army could pass. This had a very severe impact on the speed with which any army could pass through enemy territory, thereby reducing the element of surprise.

Medieval warfare actually saw very few large set-piece battles. We sometimes have a different perception, because it is the large and spectacular battles, resplendent with fully dressed battle lines complete with the gaudy colours of armorial badges on shields, surcoats and banners, which capture the imagination and which produced spectacular victories to commemorate and re-enact. However, collective wisdom in those days was to avoid these showdowns if possible, the outcome was far too unpredictable, one might well get hurt and that wasn’t the point of the game. The point was to get rich and powerful, and the way to get rich and powerful was to own land and castles to protect that land. Conflicts therefore, became a game of chess. In peacetime one expanded control over the board by creating alliances through marriage, gifts and bribes. In war one occupied castles or denied them and their productive lands to the enemy by means of destruction.

King John I understood this principle, when he released the likes of Falkes de Breauté onto the Midlands to lay waste to towns and depopulate areas or capture castles he was in effect trying to even out the balance with the invading force. The latter enjoyed far larger initial support in an England which was, after all, in revolt against their own king. When John I continued these attacks during the winter, generally seen as a time for a bit of R&R, he was in effect playing speed chess. Prince Louis was too late in fully comprehending the crucial importance of castles, if he had moved to Dover earlier, he might have captured it. By the time he finally got there Hubert de Burgh and 140 stout defenders manned the walls. Although the French executed aggressive assaults against the castle, it was to remain in royalist hands and continued to be a considerable thorn in Louis’ side for the duration of the war.

When King John died in 1216, the destructive campaigns in the Midlands and Anglia had achieved more of a parity between the actual resources available to the French and their rebel allies and those available to those loyal to John’s royalist cause. Add to this the failure of French progress in the Southeast and we more or less have a stalemate. Something needed to happen in order to break that stalemate and prevent the war from stretching out over a decade or more, with all the destruction of economic resources that implied for the kingdom. From that perspective, it makes sense that several historians have mentioned that just about the best thing King John could have done at that moment, was to die, which is what he conveniently did.

John’s death tipped the balance in favour of the royalists. Many of the rebels were no longer comfortable with the fact that they were in league with a foreigner, something that wasn’t helped by Louis public admission that he didn’t really trust men who had betrayed their own king, and the Pope’s disapproval of the enterprise. Louis placed his trust in his French compatriots instead. Public opinion, for what it was worth, noted that foreign troops were burning their villages, despoiling their fields and mistreating their wives and daughters. They probably didn’t know whether these foreigners were Frenchmen or foreign mercenaries in John’s service, but as treatment at the hands of both was similar, it probably didn’t matter all that much. What mattered is that they wanted the foreigners out. With King John gone, and the rebellion being very much based on personal grievances against John, not his young son Henry, rebels came to share the view that foreigners had best stay in foreign places, and switched sides again. They did so in numbers large enough to sway the balance in favour of the royalists. All that was needed now were the requisite military victories.

Having had a look at the immediate physical setting, as well as some of the attached political and military issues, we can now move to the plot: The war itself.

THE PLOT

As has been mentioned previously, Louis was married to the granddaughter of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, and it was on the basis of this marital alliance that the barons had invited Louis to invade in order to “prevent the realm being pillaged by aliens”, by which they referred to John’s mercenary troops. The baronial delegation had visited Louis in the autumn of 1215, and Louis first responded by sending over contingents of French troops who were to aid the barons, for armed rebellion had already begun, and Rochester Castle was besieged by John.

Apparently the barons weren’t the only ones enlisting French help. Holinshed makes mention of a French knight by the name of Hugh de Boves, who crossed from Calais to Dover at John’s invitation, with quite a large number of soldiers and their wives and children, although we’ll dismiss the number given by Matthew Paris (40,000 souls) as being somewhat unrealistic. Before these ships managed to reach Dover harbour, however, the ships were caught in a violent storm, and all of them sank. Holinshed says that the drowned bodies of men, women and children were subsequently washed up on beaches all along the south-eastern coast.

In May 1216 Louis himself crossed the channel with an army, he himself as guest on board of the ship that belonged to the invasion fleet’s admiral, Eustace the Black Monk. They landed on the Isle of Thanet, after which Louis crossed to the mainland and set up camp at Sandwich. Here, according to Holinshed, “there came unto him a great number of those lords and gentlemen which had sent for him, and there every one apart and by himself swore fealty and homage unto him….as if he had been their true and natural prince.”

John withdrew to Winchester, and Prince Louis, skipping Dover Castle, advanced to London. There he received a royal reception by rebel barons and the citizens of London. Gerald of Wales summed up the prevailing mood: "The madness of slavery is over, the time of liberty has been granted, English necks are free from the yoke." The citizens of London were so overjoyed at being liberated that they couldn’t help themselves but swarm into the Jewish quarter, stealing everything they could lay their hands on and dispatching any Jews who offered resistance. Such expression of joy tells us it must have been quite a party.

Louis was proclaimed (but not yet crowned) king at St.Paul’s cathedral in a well-attended ceremony. John made a further withdrawal to the north, and by the 14th of June Louis had captured the old capital of Winchester, by conquest or homage, he could now lay claim to more than half of England.

Despite this, the seeds of destruction were already sown in Kent. Dover Castle was still to be subjugated, and something odd had happened in the depths of the Weald. Holinshed reports: “There was a young gentleman in those parts named William de Collingham, being of a valorous mind and loathing foreign subjection, who would in no wise do fealty to Lewis.” Holinshed explains that Collingham (Cassingham) assembled around a thousand archers, and “kept himself within the woods and desert places whereof that country is full, and so during all the time of this war showed himself an enemy to the Frenchmen, slaying no small numbers of them, as he took them, at any advantage”.

The reference to the number of slain Frenchmen suggests that William de Collingham, a.k.a. William of Cassingham, also known as Willikin of the Weald, was reasonably successful in his resistance, a conclusion strengthened by further exploits in later phases of the war. The last part of the quote is a hint at the type of warfare Willikin’s archers would have been involved in.

We know that English archers did not yet possess the great war bows which would make their continental debut about 120 years later at Cadsant and Sluys, the opening battles of the Hundred Years War. None-the-less, we know that a distinction can be made between the regular household bow most peasants might have had, and the bows in possession of the foresters who were skilled archers and employed these skills in almost permanent skirmishing against poachers and the pursuit of deer and boar in the hunts which the Norman aristocracy valued so highly.

When archery begins to make a serious appearance as a significant military component it is notable that the primary groups of archers are drawn from specific regions, namely those with many forests and therefore foresters, i.e. Gwent, Chester, Sherwood and the Weald. So if there were ‘special’ bows around at this time, it’s likely that the men of the Weald would have had access to them. The big question, of course, is what draw weight these hunting bows would have had. As mentioned, the bows had not yet achieved the status and the strength of the 14th century war bows.

We know that Yew, the magic ingredient of the 14th century war bows, had actually been in use for a long time, it seems to have been recognized as the ideal bow wood across Northern Europe for thousands of years. The difference, however, between ancient bows and 14th century bows, is that the bowyers of yore only used the heartwood of Yew, not having realized what a powerful combination could be had from using both heartwood and sapwood, the elasticity of which had been recognized by the 14th century. The next question is, when was this discovered and when did such dual Yew type bows start making a general appearance? There are some very alluring references in some of the older Robin Hood tales which suggest that Robin, at least, is making a distinction between two kinds of bows, preferring a more powerful sort and scoffing those who draw to the chin instead of the ear. However, as these ballads weren’t committed to paper until the 15th century, these may well have been ‘modern’ additions allowing 15th century archers a bit of a laugh at the expense of ignorant rustic yokels from the olden days.

I’m willing to venture that the elite hunting bows at the beginning of the thirteenth centuries could well have reached draw weights of 90 to 100 pounds. This is a far cry from the 120-140 pound war bows, but never-the-less sufficient to pack a significant punch, as anyone who has ever shot a 90 pounder can confirm.

As for tactics, these men, were superbly trained. Not in open battle against heavily armoured knights of course, which is probably why we don’t find them in open battle (yet). However, as foresters and hunters, they would have been extremely familiar with the layouts of the local woods. It is my guess that Willikin would not have kept his thousand archers in the same place. The task of feeding such a significant number, the chances of keeping them concealed and the increased risk of disease: All combined it seems like a huge investment for a very low return, for that convoy of French supplies with two score armed guards is just as likely to succumb to two dozen archers as they are to a thousand.

There are also indications that Willikin employed psychological warfare, which I infer from various references to Frenchmen being beheaded or hung. One can imagine being on French convoy duty (most shipping would have come through to the southern channel ports, Dover was not an option as it was still in enemy hands), guarding wagons making their way over rough roads and then encountering countrymen, perhaps even men you knew, dangling from trees, strangled by a hemp noose, or encountering nothing but their heads affixed to a stake set by the roadside.

Whatever was happening in the Greenwood, the French quickly learned to fear the place and the lack of safety on the roads cutting across the Weald hampered their supply operations. Operations which, for example, would have been necessary for the siege of Dover Castle, for Louis had turned his sight on Dover Castle at last.

Find out more in the next part of England Invaded: High Noon at Dover Castle.

SERIES CONTINUED HERE

- England Invaded (5): High Noon at Dover Castle

We reached the place where we focus on some of the action taking place in Kent during the First Baron's War. Specifically at Dover Castle and in the Weald.