- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- Ancient History

Goddess Cults in the Ancient Aegean and the Indus Valley

Introduction

There exists strong evidence for the evolution of a goddess cult in the Aegean area, specifically at the site of Catal Huyuk, spanning from Neolithic times, through the Minoan civilization, and even into classical Greece. In each cultural context the Goddess (later becoming one amongst many divinities) and her symbols and associations underwent changes that exhibit a chronological trend in alteration of religious conceptions and practice – they traverse the space from female- to male-deity centrality, and from domestic to shrine, palace, and temple worship. Interestingly, similar trends can be noticed in the phenomenon of Goddess worship in India. While the existence of this shift in religious sensibilities tells archaeologists much about changes in dominant, state ideology, reconstructing women's religious experience proves a more difficult task, one that requires the utilization of multiple, extensive sources of evidence. While certain approaches can hint at women's religiosity in these ancient cultures, as Brumfiel attempts to demonstrate, the task is challenging and many cautions must be exercised in order not to arrive at misleading conclusions.

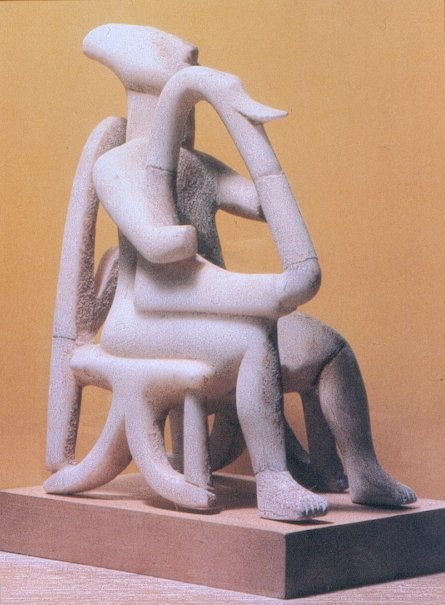

The Ancient Aegean

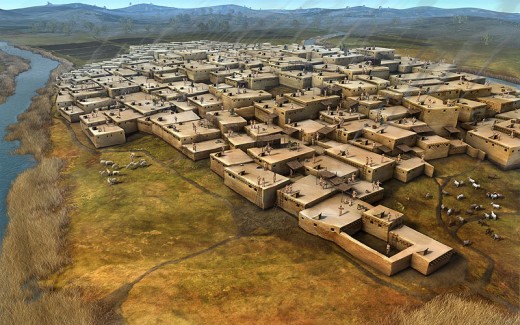

Fagan, along with many archaeologists and anthropologists, believes that the cultural shift from hunter-gathering to agrarian production caused a modification in religious practice, often from ritual hunting and sacrifice to the worship of ancestors and a chthonic goddess (80). He states that "since farming and fertility [go] together, it seem[s] logical to add an Earth Mother, a Mother Goddess, to the equation" (82). While he rightly criticizes Gimbutas for making grandiose claims of Goddess worship in "Old Europe" without citing proper archaeological evidence, he himself fails to notice the continuation and transformation of a Goddess cult in the Aegean and Asia Minor (84-5). The first indications of such a cult can be found in the Neolithic site of Catal Huyuk. Firstly, statuettes of large, robust women are common to this time and site. The statuettes have been deemed as cultic in nature for numerous reasons, most notably that they are almost always discovered in shrines (96). Images of the Goddess, which demonstrate stylistic similarities, often depict her as possessing power over animals, the most common of which are ferocious cats and bulls/bovine creatures. This information, alongside the impeccable archeological record of their provenience, allows scholars to safely assume these are indeed representations of a deity. In Catal Huyuk the Goddess seemed to have a wide range of associations. As noted she was often represented as having dominance over dangerous or wild animals, leading Fagan to propose she was the "patroness of the hunt" (97). Her fat, hourglass figure and sagging breasts also suggest connotations with fertility. This claim is further supported by representations of the Goddess in a typical birthing position and others in which she breast-feeds a child. This role was perhaps augmented to a cosmic degree, indicated by the presence of vegetable patterns and floral motifs that typically adorned her shrines. Additionally, Goddess statues are often found in "piles of grain and petaled flowers" (97). In fact, her association and connection to the underworld/earth was even symbolized in the very material (stalactites) out of which her images were sometimes carved.

By analyzing the context in which the Goddess was worshipped one can glean even further information regarding her status. Bulls’ heads and cattle horns are found in abundance in the domestic shrines of Catal Huyuk. Interestingly, these shrines "blend[ed] into residential spaces,” indicating that worship had an important connection with the domestic sphere. The basic family concerns of having enough food, procreating, farming, etc. all resonate well with our current understanding of the Goddess. While it was initially debated whether or not these "shrines" held religious significance, the consistent layout and orientation found in multiple sites indicates a widespread religious ideology. This assertion exemplifies the importance and centrality of contextualizing multiple sources of evidence in order to have adequate support to arrive at a valid interpretive conclusion. Finally, depictions of funerary practices should be considered. The most common motif represents vultures picking apart human victims. This coincides with the archaeological evidence that suggests the inhabitants of Catal Huyuk "exposed the deceased...outside the town, where vultures cleaned off the corpses" (93-4). Later, the bones were collected and interred. All these characteristics and practices associated with the worship of the Goddess get appropriated and elaborated in the Minoan context in telling ways.

The next large-scale manifestation of Goddess worship in the nearby area is evidenced around 3500 years after the collapse of Catal Huyuk with the prevalence of what archaeologists term "Cycladic Statuettes,” commonly found in farming villages of the Aegean Islands (253). Unfortunately, not much is known about these intriguing specimens, due to the fact that the majority of them have been removed from their primary context by looters and can only be studied within the confines of private collections, providing “a classic example of how information about religious beliefs [can be] lost when archaeological contexts are destroyed" (253). Nevertheless, archaeologists have deduced that the figurines were often removed from funerary contexts, and that their stylistic attributes, and the evolution thereof, may indicate Mother Goddess worship. Additionally, these figurines were sometimes discovered in pairs, and were broken in order to be placed into tombs, signifying that their initial use was not funerary in nature (and thus, perhaps, ritual). Regardless, it must be kept in mind that such extrapolations are tenuous at best, considering the lack of suitable archaeological provenience and inquiry. However, archaeologists do know much more about Minoan religion, which is coeval with the Cycladic Statuettes and in fact share many important similarities with the Goddess tradition of Catal Huyuk.

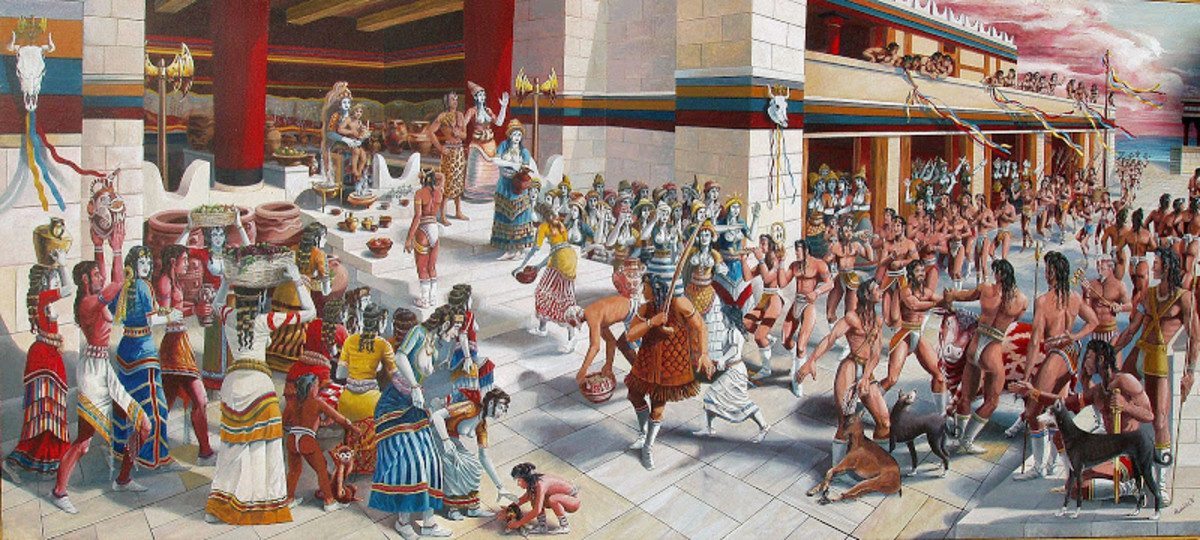

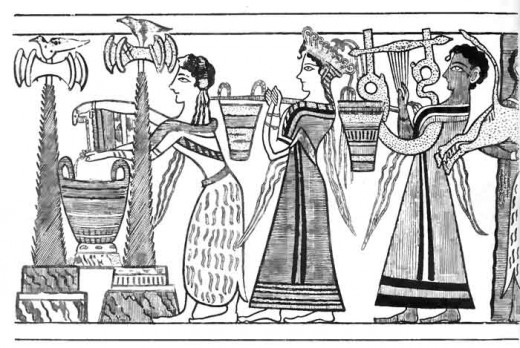

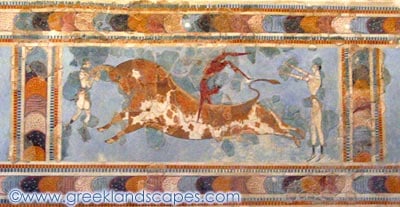

Minoan representations of the Goddess maintain her association with animals. On the Aghia Triadha sarcophagus a pair of griffons draw the Goddess’s chariot. These seem to be her main familiars in the Minoan context, but she is also portrayed with cats and lions, as found on a seal from Knossos (235). Curiously, there is another individual in the chariot with the Goddess, either a priestess, which would indicate that women held important roles in religious worship and administration, or instead the picture reveals worship of Twin Goddesses, which could be associated to the fact that Cycladic figurines were found in pairs. If this is the case, it marks the beginning of the fragmentation of the Goddess into multiple deities. Nonetheless, the Goddess’s chthonic and subterranean connotations remain unchanged, evinced in statues of bare breasted priestesses holding live snakes (an animal that represents the underworld and the cycle of life and death through the shedding of its skin) (241). Fertility motifs are also obviously present (bare chest), and are emphasized in "her presence among plants and animals" (240). The role of bulls in Goddess worship is greatly elaborated by the Minoans, so much so that "horns of consecration" are now considered telltale signs of Minoan cult activity. Likewise, bulls become the preferential sacrifice of the Goddess, clearly characterized on one side of the Aghia Triadha sarcophagus. The bull offering is obviously religious in nature, due to the presence of common cult signifiers (namely horns of consecration, double axes, rhytons, and altars), ritual procession, the directed attention of the participants towards the approaching Goddess on the adjacent side, ritual dress, and the presence of sacrificial and musical accompaniment. It has also been hypothesized that the bull leaping frescoes of Knossos depict another form of sacrifice, that of young men (247). Whether or not this is true, the fact that "goddesses and bulls adorned Knossos's walls" cannot be denied (225). Finally, I find it interesting that the Minoans also exposed corpses to the elements, later storing or discarding the remains (230). While I don't believe this practice has ever been explicitly connected with Goddess worship per se, its presence in both Catal Huyuk and Minoan society is fascinating.

There ends the similarities between the religions of Catal Huyuk and Minoan society. Possibly even more instructive, however, are the changes that occurred in Mother Goddess worship. The most crucial shift was perhaps the relocation of the locus of worship. In Catal Huyuk shrines were found in domestic contexts, where in the Minoan civilization religious activity was largely centered in "the courtyards and adjacent shrines" of palaces (232). Thus, cult worship found its new home in "the Throne Room,” reinforcing the belief that the priestly families’ “close relationship with the Goddess formed the basis of their political, economic, and spiritual power" (242-3). While Minoans still "revered the deities associated with...natural features of the dramatic island landscape" in "shrines thousands of meters high" and in "remote mountain location[s],” the gradual shift in worship from domestic to stately, natural to man-made, was already underway and would reach its climax in Greek civilization. The other crucial difference to note is the appearance of a male god, who was characterized "as a Master of Animals, represented by a deity holding animals in a submissive position" (240). Aware of the Goddess's association with animals this, to me, clearly constitutes the beginning of the subjugation of the Goddess, for "unlike the goddess, who fed and tended wild animals, the god hunted beasts and corralled them. He controlled nature, he did not feed it” (242). While "the Minoan goddess is larger than the male" when depicted side-by-side, his very presence indicates a shift in religious consciousness, and these early seeds of change come to full bloom in Classical Greece.

After the collapse of the Minoan civilization at the hands of marauding Mycenaeans, the small, modest shrine at Phylakopi is a testament to the continuance of Goddess worship on a more localized scale. However, the Goddess cult was radically altered when appropriated by the Greek culture. The Goddess soon lost her femininity, and, after being filtered through androcentric ideology, her roles and associations were split up and relegated to numerous goddesses. For example, Artemis and Athena were both strictly virgin goddesses, stripped of any hint of fertility. Although vestiges of original Goddess ideology persisted in Artemis’s association with childbirth and her role as patroness of children and animals, the Goddess’s original stature was hugely reduced. The figure of Athena also harbored strictly "un-Goddessly" characteristics. Her virginal status has already been noted, and to emphasize the amputation of any feminine connotations she wasn't even born of a woman, and instead was thought to have emerged from Zeus's skull. This "infertility" was more poignantly manifested in her role as a goddess of war, nothing of which is more opposed to fertility and the continuation of life. Aphrodite reveals other interesting developments. While she wasn't a virgin, her sphere of influence involved erotic love and not procreation. Furthermore, she was very weak, a far cry from the powerful and commanding Goddess figures of Crete. As for male gods, I find it interesting that Zeus, the head of the Classic Greek pantheon, was often associated with bulls. If traditional Goddess symbolism holds weight here, which it may or may not, it would reveal an interesting reversal, for the common sacrificial victim came to dominate, command, and give rise to the deity for which it was once slain. Here then, the shift from a strong, central female deity to the supremacy of male gods over weak imitations and fragmentations of a once mighty female Goddess was complete. The last point to highlight is that the transition from domestic worship to palace/state worship continued. In ancient Greece large temples were the setting of cultic worship, oftentimes providing service for large demographic areas in highly populated cities. While shrines and temples were erected in mythically important places, direct worship of sacred landscapes, as was typical in the past, decreased. Let us now investigate similarities in Goddess appropriation from other geographic and historical contexts.

The Indues Valley -- A Comparison

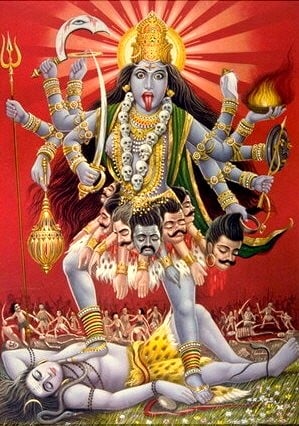

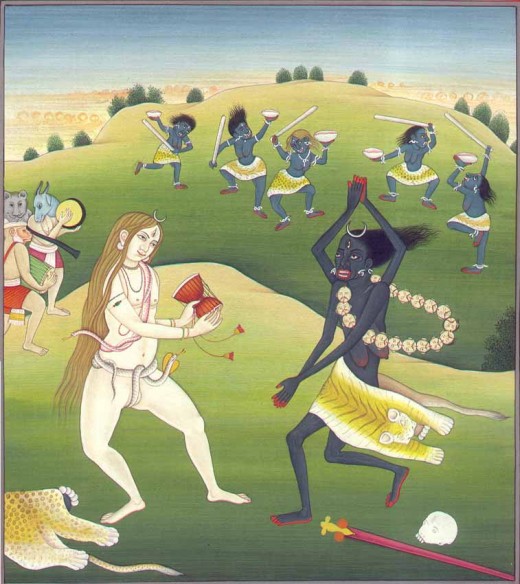

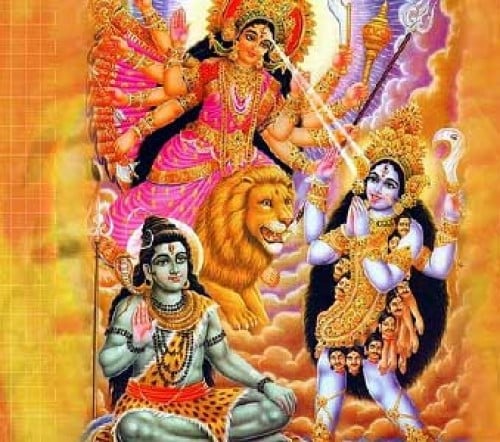

India has similar Goddess traditions that reach back to the early stages of the culture’s existence. There, too, the earth was conceived of as female, and her shrines were the very living landscape. Rivers, rocks, and trees held sacred significance in pre-Brahmanic times, and do so to this day at the local level. Interestingly, although very little information can be discerned regarding pre-Aryan times, the single religious icon that has been identified is a female figurine, believed to be something of a Goddess figure. Although a connection to modern Goddess worship shouldn't be hastily made, the mythic history of Goddesses indicates a very long tradition of Goddess worship. As the Brahmanical structure grew, it tended to incorporate deities into its trans-local pantheon instead of violently rejecting gods and goddesses it encountered. However, upon appropriation, Brahmanism altered the roles and functions of goddesses in order to have them agree with its rather androcentric ideology. In the case of the goddess Sarasvati, her original role as the living goddess of a particular river was altered to that of the patroness of "speech, learning, culture, and wisdom", characteristics much more akin to traditional Brahmanism than local practice (Kinsley 57). Parvati, once a goddess who "dwelled in the mountains" later became the domesticated housewife of Shiva (41). While mythological remnants of her darker qualities can still be found, the myths tend to emphasize "Parvati's milder side" (46). Another case is that of the warrior goddess Durga, who was associated with lions and large cats. Upon appropriation, she maintained her strong, militaristic connotations, but was also given the role of a loving mother, both of which seem quite suitable for male warriors. And when the gods and demons searched for the elixir of immortality, and instead found the goddess Laksmi, her "associations with the sap of existence that underlies or pervades all plant and animal life" became solidified (27). However, she was quickly taken as a prize by Visnu, and soon represented the paradigmatic devoted wife and housekeeper, and was thus domesticated. Even the most ferocious and wild of goddesses, Kali, was wed to Shiva and tamed, and although her antinomian worship is still present in Tantric circles, even they show evidence of conservative, Brahmanical influence. All of these examples are shared in order to demonstrate similar trends of feminine subjugation in the appropriation of Goddess traditions in both ancient Greece and Brahmanical India.

Dangers of Lack of Evidence -- an example

Elizabeth Brumfiel attempted to extrapolate evidence for local resistance to misogynic Aztec ideology by analyzing temporal changes between gendered representations in figurines. She compared the frequency of state and local samples from two different time periods (pre- and post-Aztec) and from three different sites, whose geographic distances from the Aztec capital correlated with varied amounts of confrontation with state ideology (or so she assumed). She discovered that in the far-removed site of Xico there was no change in gendered representations. The site of Huexotla, believed to represent a high level of interaction with state ideology, demonstrated a heightened awareness of state ideology and an increase in the ratio of female to male figurines. Finally, finds at Xaltocan, which came under Aztec control rather suddenly, showed a reduction in ungendered figurines and an increase in the female to male ratio, as in Huexotla. Brumfiel concluded that this evidence indicated "an ideology of resistance that sharply contested the official gender ideology of the state" (155). I believe Brumfiel was correct in assuming that the archaeological record would show evidence in alterations in ideology. Indeed, the almost automatic, and sometimes unconscious, tendency for humans to externalize their experiences and ideas is in no way contested. However, as mentioned above, it seems faulty to focus solely on one mode of human expression, as I indicated in the examples above. A much more comprehensive approach is necessary to establish a more accurate cultural reconstruction. Additionally, the fact that Brumfiel examined such a small sample size is incredibly misleading. If one is going to attempt to reconstruct an aspect of ancient society based solely on a single mode of symbolic expression the sample size should be larger and more widespread to ensure that one is dealing with a representative sample. Granted that the archaeological record does not always provide such a plethora of evidence, making grandiose claims on such minuscule physical evidence greatly jeopardizes their accuracy.

Conclusion

Taking all this information into account, how can one accurately reconstruct the societal role and religious experience of women in ancient times? The task is challenging to say the least, but it is more than possible when multiple sources of archaeological evidence are properly contextualized and utilized. In Greece, there is clearly a gap between the powerful tales and images of goddesses and the living reality of women. This can be demonstrated archaeologically by inspecting the arrangement of domestic space in Athens. There, the demarcation of gendered space was quite obvious, for the buildings were divided into two segments, one for men, which was closer to the entrance, and the other for women, which was further from the street or upstairs if the house was configured in such a way. Furthermore, surviving legal texts reveal that women could never achieve independent status, and were instead always categorized as a dependent of a male. Moreover, in courts, the names of women were never uttered. Instead, they were referred to indirectly through patriarchically centered ties of matrimony or kin. However, inscriptions unearthed in temples reveal that women did have autonomous religious roles. For example, the cult of Demeter was exclusively for women, and women both administered and participated in this religious context. This illustrates the fact that no one piece of evidence can allow an archaeologist to fully reconstruct an accurate picture of women's roles in society and religion. Based solely on the gross changes the Goddess tradition underwent at the hands of Greek society, one could erroneously conclude that the status of women became more and more liminal. If the legal papers and manipulation of domestic space described above were considered in isolation, one would arrive at an even more dismal and extreme picture. Conversely, the inscriptions relating to the cult of Demeter, taken alone, would suggest that the status of women was rather high, and perhaps not far removed from that of the priestesses of Crete. However, all these reconstructions would fail to approach the more realistic, precise, and complex picture painted when all are taken into account simultaneously, indicating that in order to reconstruct the most accurate historical account possible the archaeologist must utilize as many different sources of evidence as s/he is able. The apparent discrepancies between ideology and reality in classical Greece force one to critically reconsider the perhaps erroneous assertions of matriarchichal administration in Minoan society and Catal Huyuk. While matriarchy could indeed have been present, as hinted at in the Greek tales of the Amazons of Asia Minor, a more thorough investigation that employs numerous sources of evidence would be necessary to bolster such a claim. However, archaeologists are sometimes not fortunate enough to have a plethora of available data, and this can force them to make somewhat problematic and tenuous claims.

So what have we learned? Firstly, we must accept the fact that archaeology often leaves us with a dearth of information in hopes to make strong and sweeping claims about ancient society and religious life. Nevertheless, we do our best, and it seems that, in general terms, there existed pervasive worship of a Goddess in Neolithic times in the Aegean area. She was associated with the animal kingdom, fertility, procreation, life and death, and had quite cosmic significance. Over time, and in the contexts of new ideologies and cultures, she was dismembered and dislocated, her roles slowly relegated to multiple goddesses, or even male gods. Male gods eventually ruled the pantheon. This process mirrored a shift in the locus of religiosity from the domestic space to state or city-run temples. The process of accommodation, modification, and subjugation of the Goddess and goddess-figures can also be noted in the Indus Valley and the Brahmanical appropriation of native and local Goddess beliefs. Here, too, religious power was taken from the Earth, which was the Goddess’s body, and re-located to that of the priestly educated class. While we must be mindful in attempting to reconstruct past women’s religious experience, due to the fact that we have such scant evidence, and reality, as it is today, is complex and varied in astounding ways, it would seem safe to postulate that women’s religious and cultic power and functions declined alongside the identity of the Goddess in these ancient contexts.