Love is Blind: Why We Love Who We Love & Repeat Our Relationship Patterns

The Role of Our Mind in Relationships

Humans seek to establish close intimate relationships in order to maintain life partners and companions to share their experiences of life. When seeking out potential mates, individuals may have the goals of marriage and children in their minds or simply wish to engage in the pleasures of close, sexual relationships with romantic partners. Regardless of motivation, there exist numerous positive benefits from interpersonal relationships such as increased self-worth, enhanced self-esteem, longer life span, and overall increased mental health (Sanchez, Good, Kwang, & Saltzman, 2008). With all the positives inherent in close relationships, no wonder people continue to seek and establish such relationships despite past heartaches and numerous unsuccessful attempts. However, interpersonal relationships sometimes lead to violence, abuse, pain, and divorce. We often see our friends, family members, and co-workers involved in marriages or romantic relationships that seem from our vantage points destructive, unhealthy, or involve otherwise unappealing circumstances.

Understanding the relationship between cognition and emotion as they relate to interpersonal relationships provides a basis for insight into both why individuals may remain or repeat negative relationships and how to improve the quality of interpersonal relationships. Since humans will continue to seek out interpersonal relationships, such work on the cognitive nature of relationships may benefit society by contributing to the overall health of these unions – stabilizing families and increasing mental well-being. The purpose of this article is to examine the role of cognition in interpersonal relationships to discover the ways in which thinking patterns influence such relationships in order to establish the points at which possible interceptions may be made to improve the quality of human relationships. Cognition specifically impacts our attention and attraction to potential mates, provides knowledge of mate trait preferences, and organizes knowledge constructs associated with the nature of interpersonal relationships. Studying the active role of cognition in romantic relationships provides insight into how cognitive dissonance in relationships leads to relationship dissatisfaction. As a result, information may be obtained on the cognitive nature of bad relationships, how to break negative relationship patterns, and how individual thought patterns may damage personal relationships.

Flowers of Love

How We Choose Our Mates

Cognition factors into mate selection by focusing attention to and influencing interpretations of attraction, as well as determining mate trait preferences. Initial attraction involves the process of gathering the attention of potential mates. Gaze direction and facial features interact in the methods of perceptual processing in order for individuals to determine the intentions of others. In this manner, the emotional expressions of the face determine if others readily recognize gaze attention as directed towards themselves. The communication oriented expressions of happiness and anger such as smiling or scowling generate perceptions that direct attention, as individuals recognize and acknowledge these communications (Lobmaier, Tiddeman, & Perrett, 2008). Positive expressions combine with gaze direction to generate perceptions of wanted attention from others. Cognition works to recognize and process these signals as invitations for interpersonal contact, illustrating the role of cognitive processing on visual stimulus in the mating process.

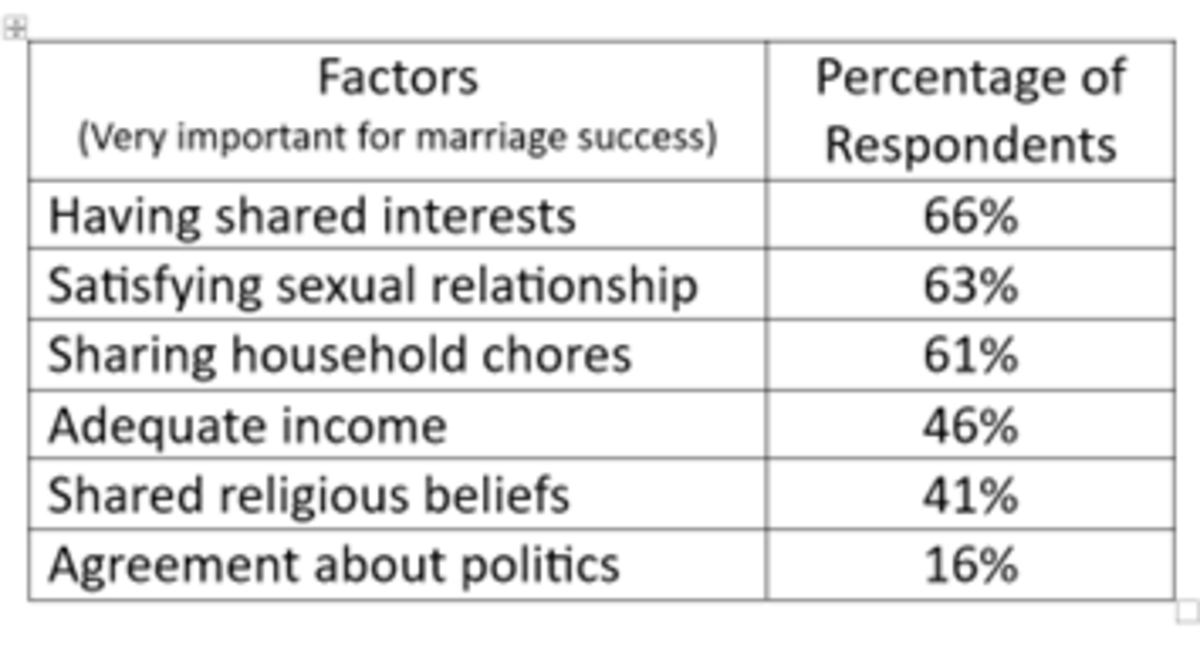

In addition to the visual processing of gaze attention, individuals also maintain cognitive representations of the desired characteristics important for potential mates. Prominent mate preferences include physical attractiveness, financial stability, emotional stability, and pleasant disposition. These traits tend to be relatively stable preferences desired for potential mates, illustrating that individuals maintain specific cognitions of what attracts them to potential mates as active knowledge constructs (Shackleford, Schmitt, & Buss, 2005). These characteristics represent conscious knowledge of the determinants that may be necessary for happy interpersonal relationships. In other words, individuals do not set out to establish interpersonal relationships with disagreeable, cranky people. Such mate trait preferences represent the sites at which cognition interacts with the biological forces of attraction. Heterosexual males fail to just be attracted to any heterosexual females. Instead, there remains a cognitive process of desired qualities that facilitates such unions or at least determines expectations of whether or not such unions will last. Potential mates remain cognitively aware of the need to present themselves in ways that reflect the embodiment of these desired traits, as they seek out individuals with these desired traits.

Factors of mate selection such as physical attractiveness depend of preferences generated in part by culture. There exists some evidence that environments that encourage relationships based on independent choice in potential mates seem to maintain high physical attractiveness stereotyping (PAS), rating physical attractiveness as integral to positive life outcomes (Anderson, Adams, & Plaut, 2008). In these cultures, physical attractiveness is deemed an extremely important quality for positive life outcomes – attractive individuals have successful, happy lives and unattractive people do not. As a result, physical attractiveness is very important in these cultures for the attraction of mates and the development of interpersonal relationships. In contrast, cultures that emphasize interdependent relationships, communal approval and acceptance of the relationship, the development of interpersonal relationships regulates relatively low importance to PAS for the generation of positive life outcomes (Anderson, Adams, & Plaut, 2008). For such individuals, aspects of family background may be more important to expectations of positive life outcomes than appearance. As result, trait preferences remain influenced in part by cultural experience in order to establish cognitive knowledge surrounding mate preference and components of what is to be expected from quality relationships.

Emotional Love Scripts

While cognition factors into our abilities to detect and seek out potential mates, it also works to help determine our emotional scripts for love and close relationships. Affective or emotional states remain associated with close, interpersonal relationships. Individuals often describe their significant others and relationships as involving intense feelings of love and other positive emotions, as well as strong negative emotions such as sadness and depression at a dissolution of a close relationship (Fitness & Fletcher, 1993). The close associations with emotions that embody interpersonal relationships indicate that such experiences should perhaps remain studied by affective processing mechanisms such as physiological response or self-reports. However, such efforts only gage the conscious associations that may be expressed verbally or study emotions as if they existed independent of other variables. Cognitive processing provides insight into the thinking associated with affective processes and measures the degree to which these automatic affective processes reveal cognitive knowledge of easily accessible scripts for interpersonal relationships that individuals utilize in their daily interactions with their partners (Eder, Hommel, DeHouwer, 2007). In this manner, these scripts provide the basic cognitive knowledge for individuals on what constituents a close personal relationship.

Love schemas or cognitive scripts for interpersonal relationships contain the conditions associated with the emotional states experienced within romantic relationships. Using a prototype and cognitive appraisal analysis of the emotions associated with close relationships (love, hate, anger, and jealousy) to determine patterns of knowledge that surround intimate relationships, Fitness and Fletcher (1993) examine situations associated with these identified emotions to determine the behavioral patterns that trigger specific responses. This work provides evidence for different cognitive schemas associated with each of the four emotional responses studied, revealing the existence of several general knowledge constructs associated with emotional responses that impact romantic relationships. Scripts of incidents that trigger certain emotions formulate individual understanding of which emotions should be expressed at what times and in what manner (Fitness & Fletcher, 1993). Emotional responses are not simply just physiological states but interact with our perceptions and knowledge of our environment. In this manner, we may learn to avoid situations that trigger negative emotions and include those more positive experiences in our close relationships. Too many bad events that trigger negative emotions may generate dissatisfaction within the relationship.

Why Love Dies & Why We Stay in "Bad" Relationships

Dissatisfaction in our close relationships seems to stem in part from major discrepancies in individuals’ expectations of loving relationships and their realities. Neff and Karney (2005) provide a cognitive model of love based on global and specific trait perceptions to examine long-term relationship satisfaction, revealing that discrepancies between positive global attributions and negative specific traits may lead to relationship satisfaction decline. This work provides insight into the cognitive basis of love and an explanation of how love may change and even deteriorate over time. Similar to the ways in which negative emotional responses associated with perceptions of relationship experience adversely impact the entire relationship,the specific negative traits of romantic partners may interfere or even override the global attributions of how individuals view their partners (Neff & Karney, 2005). For example, the impression that our partner is always kind and generous may become challenged by specific encounters with our partner that seem to be unkind and ungenerous. Repeated actions of unkindness may generate a global or broad view of our partner as an unkind person. As multiple negative emotions reduce relationship decline, too many negative encounters that lead to changes in our global attributions of our mate leads to relationship decline. In this manner, individuals’ initial assessments of their partners attributes come in conflict with their daily experiences with their partners. This conflict creates cognitive discrepancies within interpersonal relationships.

Cognitive dissonance between relationship beliefs and experiences may be embodied within the scripts themselves. Cognitive scripts of the love of interpersonal relationships or love schemas represent the knowledge constructs of how interpersonal relationships should be conducted. These contrasts depend on personal experience, cultural backgrounds, and learned behaviors. As a result, individual perceptions of the relationships of others may be biased from our own love schemas. Differing love schemas contribute to our failures to accurately assess the relationships of others (Aloni & Bernieri, 2004) and determine adult romantic attachment patterns (Elwood & Williams, 2007). The implications of varying love schemas include the fact that the enhancement of relationship satisfaction may be best handled through individualized examination of cognitive love scripts rather than global relationship patterns and that the specific methods that are employed to reduce cognitive discrepancies in interpersonal relationships be evaluated in comparison with love schemas. Partners who maintain different love schemas maintain conflict related to the nature of their differing relationship constructs. Such problems may involve vastly different perceptions of the same event or one partner being more highly conscious of intimacy within the relationship (Fletcher, Rosanowski, & Fitness, 1994). These discrepancies seem to exist on a higher cognitive level of conflict resulting from the basic beliefs of what constituents interpersonal relationships.

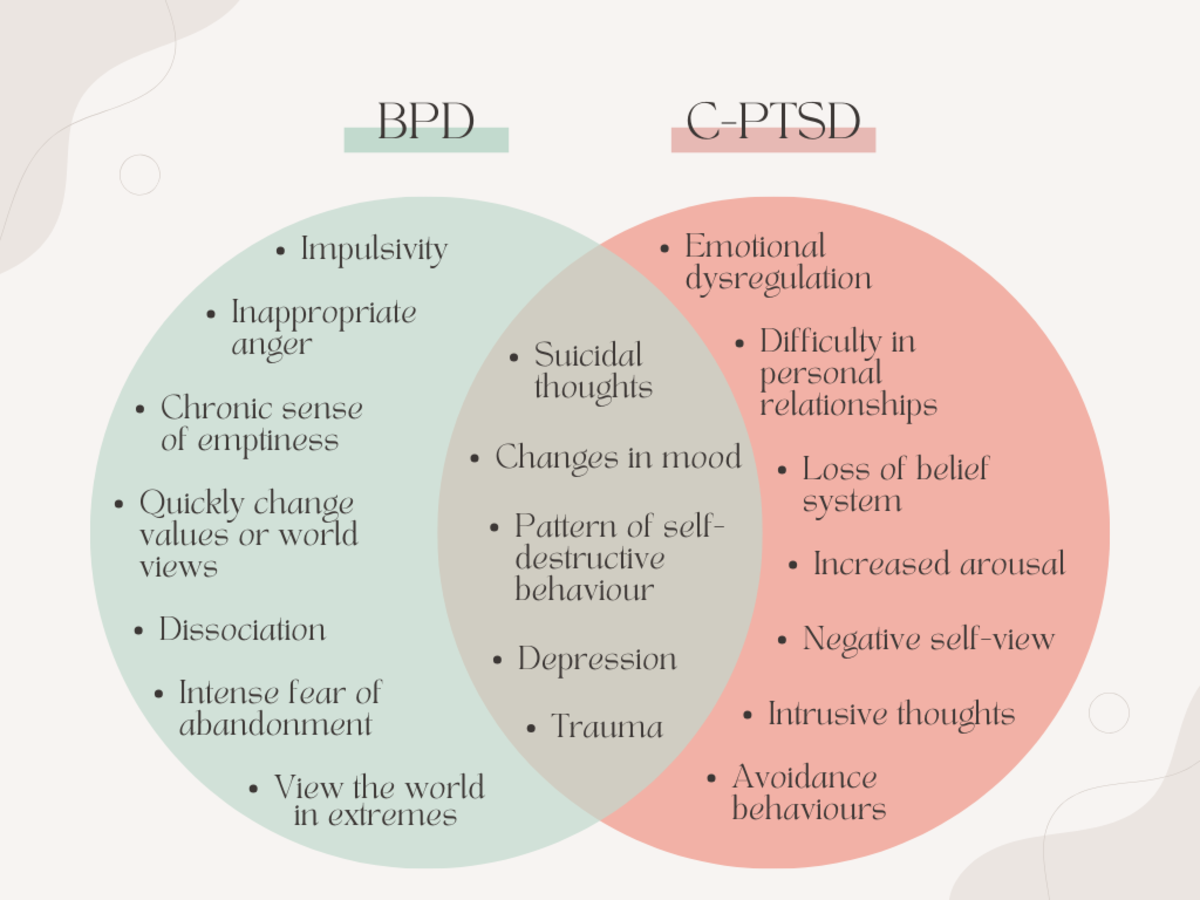

The different and varied love schemas individuals maintain reflect the complexity of the factors and experiences that determine the development of particular love schemas. While there may exist general patterns in which specific experiences tend to generate certain emotions (Fitness & Fletcher, 1993) and general agreement on likeable qualities in potential mates (Neff & Karney, 2005), the different cognitive scripts of love may explain different responses or tolerance levels for negative emotions and the expectations of the number of such emotions in interpersonal relationships. Our close relationships remain determined by the accessible knowledge constructs that are generated from past experiences and beliefs (Fletcher, Rosanowski, & Fitness, 1994). These accessible knowledge constructs reveal themselves in our patterns and attitudes about relationships. Attitudes regarding close relationships may reflect commitment avoidance patterns or influences from social networks such as being in college that encourage the engagement of “friends with benefits” relationships that never lead to long term relationships (Hughes, Morrison, & Asada, 2005). In addition, problems in interpersonal relationships may also reveal signs of pathology such as chronic depression or problems with social cognition, difficultly reading the emotions and responses of others (Allen, Haslam, & Semedar, 2006). Individuals who have experienced traumatic events may maintain post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms that include negative cognitive beliefs about unfamiliar people, which could impact interpersonal relationships beliefs (Elmwood & Williams, 2007). In addition, cognition related to self-esteem may impact degree of relationship satisfaction (Cramer, 2003). Given the various life experiences that may impact the generation of individual love schemas, the sources of relationship dissatisfaction remain multiple and hard to generalize.

Individuals seek to reduce the cognitive discrepancies in their relationships in order to improve relationship satisfaction. Ways to reduce cognitive dissonance include mechanisms such as benevolent cognitions and other means of cognitive processing to account for relationship discrepancies. Benevolent cognitions refer to the ways individuals may view the negative events in their relationships as isolated incidents that fail to impact perceptions of partners and the relationship as a whole. Such cognitions represent effective ways of dealing with mirror problems in relationships to maintain harmony and hope for the future of the relationship (McNulty, O’Mara, & Karney, 2008). The cognitive ways in which we monitor our perceptions and responses in order to preserve our personal relationships illustrate the points at which individuals may change patterns of thinking in order to improve quality of life to smooth over discrepancies and keep the peace in our relationships. Discrepancies in relationship satisfaction may involve the Ideal Standards Model. This model refers to the ideal mate standards that individuals’ utilize to evaluate existing partners. Similar to love schemas, ideal standards arise from past experiences and self-perceptions of own good qualities (Overall, Fletcher, & Simpson, 2006). When current mates fail to meet the ideal, ways to dismiss these discrepancies are employed. Such ways include rationalization of partner’s negative behaviors, increased focus on positive attributes of partner, and attempts to regulate partner’s behaviors (Overall, Fletcher, & Simpson, 2006). These attempts to reduce cognitive dissonance involve reformulations of the expected behavioral patterns of others to account for the discrepancies. Efforts at seeking to regulate the behaviors of others are the most unsuccessful, as it remains hard to change the behaviors of others without their knowledge or willingness to change (Overall, Fletcher, & Simpson, 2006). As a result, it remains easier for individuals to monitor and change their own cognitions and emotional responses to circumstances within the relationships than to change those of their partners.

Processes to reduce cognitive dissonance within relationships by changing thinking patterns may or may not enable individuals to reduce the distress of their relationships. While these efforts are often successful in relationships with minor conflict and low incidents of negativity, efforts such as benevolent cognitions may also lead to relationship dissolution or chronic relationship dissatisfaction. Ignoring major relationship problems, unhealthy relationship patterns, or major negative partner traits, individuals create relationship conditions that demand no motivation to correct negative behaviors and eventually these relationships fail (McNulty, O’Mara, & Karney, 2008). This cognitive reasoning process may contribute to why individuals stay in abusive relationships. Abused partners may justify their abuse or rationalize the negative behaviors of their partners, failing to demand changed behavior from their partners or recognize their own harmful conditions. In this manner, the very mechanisms that individuals employ to preserve their interpersonal relationships may be harmful. Serious and chronic relationship problems may be unable to be solved by these cognitive reinterpretations of perceptual responses (McNulty, O’Mara, & Karney, 2008). Pretending that violence is okay or glossing over behaviors that generate personal harm fail to improve the relationships or stop the patterns of behavior.

In addition to improper or unhealthy dismissal of important relationships discrepancies, individuals’ cognitive scripts of close relationship also maintain a tendency to resist significant change. Individuals often experience or maintain the same types of romantic relationship patterns throughout their lives. As Wegner and Gold (1995) discover, the suppression of thoughts of loss loves often leads individuals to linger over their past relationships with obsessive thinking and constant remembrances. Such obsessive thought patterns may reveal why some individuals seek similar relationship patterns to those of past relationships or remain unable to move on from a previous relationship. As a result, these individuals may be unable to move into new relationships and seek to reunite with their lost love. In addition, individuals are readily able to issue judgments of their partners and relationships abilities to meet valued beliefs of what constitutes quality relationships such as honesty or intimacy (Fletcher, Rosanowski, & Fitness, 1994). The ease to which individuals are able to offer these judgments indicates the prevalence and depth of the individualized cognitive scripts for interpersonal relationships.

Think About How We Love to Change our Relationships

Cognition impacts our attention and attraction to potential mates, organizes knowledge of desired personality traits for potential mates, illustrates individual love schemas and cognitive relationship scripts, and provides insight into how individuals reduce cognitive discrepancies to improve relationship satisfaction. The active role of cognitive processing in interpersonal relationships helps us understand human relationship patterns in order to improve such relationships. Destructive relationship patterns may represent cognitive relationship scripts that can be altered to improve the opportunities of individuals stuck in these relationship patterns to seek healthier relationships. In addition, efforts of couples to understand the sources of their dissatisfaction are improved with knowledge of how different knowledge constructs between mates create discord. The connections between the intense emotions of romantic relationships and cognition provide insight into how such emotions may be regulated and expressed in positive ways. Knowledge of the ways in which we operate from love schemas and work to modify our cognitive thought patterns in our relationships provides the first step to understanding the role of cognition in interpersonal relationships.

Future investigations in the cognitive nature of romantic relationships may bring understanding to reasoning behind destructive relationship activities such as extramarital affairs or the alternative relationship patterns of polygamous relationships. Cultural investigations to establish the impact of ethnicity, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, race, or gender on thinking patterns related to interpersonal relationships may help provide therapy or mental health services for a diverse group of couples or individuals seeking to increase the quality of their interpersonal relationships.

References

Allen, N. B., Haslam, N. & Semedar, A. (2006).Relationship patterns associated with dimensions of vulnerability to psychopathology.Cognitive Therapy and Research, 29(6), 733-746.

Aloni, M. & Bernieri, F. J. (2004).Is love blind?The effects of experience and infatuation on the perception of love. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 28(4), 287-295.

Anderson, S. L., Adams, G. & Plaut, V. C. (2008).The cultural grounding of personal relationship: The importance of attractiveness in everyday life.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(2), 352-368.

Cramer, D. (2003). Acceptance and need for approval as moderators of self-esteem and satisfaction with a romantic relationship or closest friendship.The Journal of Psychology, 137(5), 495-505.

Eder, A. B., Hommel, B., & De Houwer, J. (2007). How distinctive is affective processing?On the implications of using cognitive paradigms to study affect and emotion.Cognition and Emotion, 21(6), 1137-1154.

Elmwood, L. S., & Williams, N. L. (2007). PTSD-related cognitions and romantic attachment style as moderators or psychological symptoms in victims of interpersonal trauma.Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(10), 1189-1209.

Fitness, J. & Fletcher, G. J. O. (1993).Love, hate, anger, and jealousy in close relationships: A prototype and cognitive appraisal analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(5), 942-958.

Fletcher, G. J. O., Rosanowski, J., & Fitness, J. (1994).Automatic processing in intimate contexts: The role of close-relationship beliefs.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(5), 888-897.

Hughes, M., Morrison, K., & Asada, K. J. K. (2005).What’s love got to do with it? Exploring the impact of maintenance rules, love attitudes, and network support on friends with benefits relationships.Western Journal of Communication, 69(1), 49-66.

Lobmaier, J. S., Tiddeman, B. P., & Perrett, D. I. (2008). Emotional expression modulates perceived gaze direction.Emotion, 8(4), 573-577.

McNulty, J. K., O’Mara, E. M., & Karney, B. R. (2008).Benevolent cognitions as a strategy of relationship maintenance: “Don’t sweat the small stuff”. . . But it is not all small stuff. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(4), 631-646.

Neff, L. A. & Karney, B. R. (2005). To know you is to love you: The implications of global adoration and specific accuracy for marital relationships.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(3), 480-497.

Overall, N. C., Fletcher, G. J. O., & Simpson, J. A. (2006). Regulation processes in intimate relationships: The role of ideal standards.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(4), 662-685.

Sanchez, D. T., Good, J. J., Kwang, T., & Saltzman, E. (2008). When finding a mate feels urgent: Why relationship contingency predicts men’s and women’s body shame.Social Psychology, 39(2), 90-102.

Shackelford, T. K., Schmitt, D. P., & Buss, D. M. (2005). Mate preferences of married persons in the newlywed year and three years later.Cognition and Emotion, 19(8), 1262-1270.

Wegner, D. M. & Gold, D. B. (1995).Fanning old flames: Emotional and cognitive effects of suppressing thoughts of a past relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(5), 782-792.