- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

The Fall of Richmond

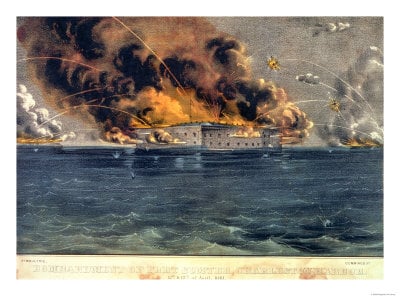

On 12 April 1861, Union soldiers stationed at Fort Sumter, on a small island near Charleston, South Carolina, woke in the early hours to the sound of Confederate batteries opening fire upon them. The bombardment continued unabated for the next 34 hours until the Union soldiers finally surrendered.

This surprise attack signalled the beginning of a dark time in American history. The coming civil war would divide a nation, pitting friend against friend, brother against brother.

After four long years, the war ended with the Confederate surrender at Appomattox shortly after Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederate States, fell to the Northern forces.

The Jewel of the South

Before the Civil War, Richmond was already a bustling city with a thriving international import/export trade. In exchange for Southern cotton and tobacco, Richmond and the rest of the South received regular supplies of coffee, spices, slaves and other products from different countries.

The business district included carriage manufacturers, slave traders, hotels, newspapers, restaurants, private schools, druggists, doctors, saloons, dentists, five foreign consulates, flour mills, a paper mill, saddle and harness makers, gunsmiths, a sailmaker, soap and candle manufacturers, two rolling mills, a canal and five railroads. The Richmond and Danville Railroad would become vital during the war in connecting Richmond to the rest of the Confederate states.

Just a Small, Southern Town

With a population of 38,000 before the war boom, Richmond was the second largest city in the Confederacy just behind New Orleans. Despite having all the trappings of a cosmopolitan metropolis, Richmond still retained its small-town charm. This could be attributed to the continuity of the citizenry with the leading, socially-elite families having known each other for decades. Richmond was the quintessential Southern belle: charming, fashionable, unassuming.

Richmond Becomes the Confederate Capital

In May 1861, the Confederate Congress voted to move the capital of the Confederate States from Montgomery, Alabama. Owing to its importance and proximity to the majority of the fighting, overnight, Richmond became the capital, military headquarters, transportation hub, industrial heart, prison, and hospital centre of the Confederacy. This distinction made Richmond a prime target for the Northern military.

Washington D.C., the Union capital, and Richmond were only 100 miles apart. However, unlike Richmond, who had witnessed more than its fair share of fighting, Washington was never seriously threatened.

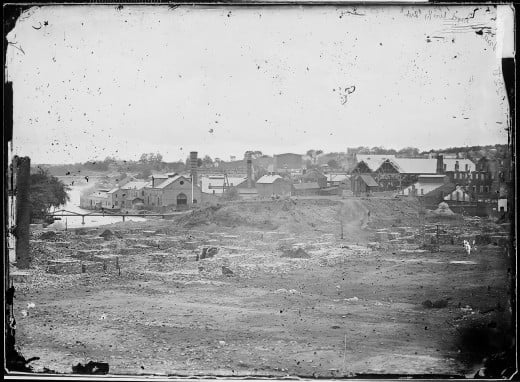

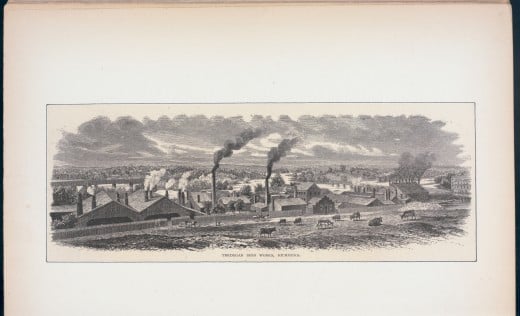

Geared for War

Thirteen working foundries made Richmond the iron-manufacturing capital of the South. The Tredegar Iron Works produced over 1,100 cannons as well as mines, torpedoes, propeller shafts and other war machinery. Richmond Laboratory manufactured more than 72 million cartridges in addition to grenades, gun carriages, field artillery and canteens. The Richmond Armoury had an production capacity of 5,000 small arms a month.

War Brings Change

War brought many changes to Richmond, the most notable among its inhabitants. The population rose sharply from 38,000 to 128,000 putting a strain on the city’s infrastructure and resources. In addition to hundreds of military regiments from other Confederate states stationed here, there were hundreds of government employees for the offices supporting the war. Soon less desirous denizens poured into the city.

Speculators, gamblers, drifters, prostitutes, all manner of unsavoury characters arrived daily to make Richmond their home. In their wake, saloons, gambling halls, billiard parlours, cockfighting dens and brothels sprung up around the city to cater to these people.

One city editor summed up the situation thus, ‘'With the Confederate Government came the rag, tag and bobtail which ever pursue political establishments. The pure society of Richmond became woefully adulterated. Its peace was destroyed, its good name defiled; it became a den of thieves, extortioners, substitutes, deserters and blacklegs.'

The once demure Southern belle had grown into a brazen harlot

The End is Nigh

Confederate victory seemed assured as the Southern armies won notable battles early in the war. By the start of 1865, however, events on the battlefield had taken a turn for the worse.

Fort Fisher in Wilmington, North Carolina ensured their port remained open to blockade runners, those 'heroes' of the South who smuggled goods and supplies past the Union blockade to the military and civilian population. In January 1865, the Union forces took Fort Fisher. The crippling repercussions were felt in Richmond and throughout the South.

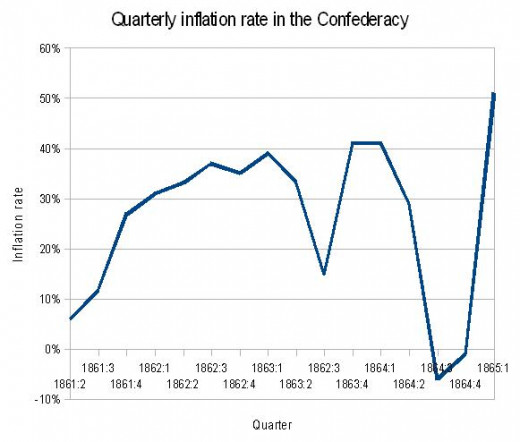

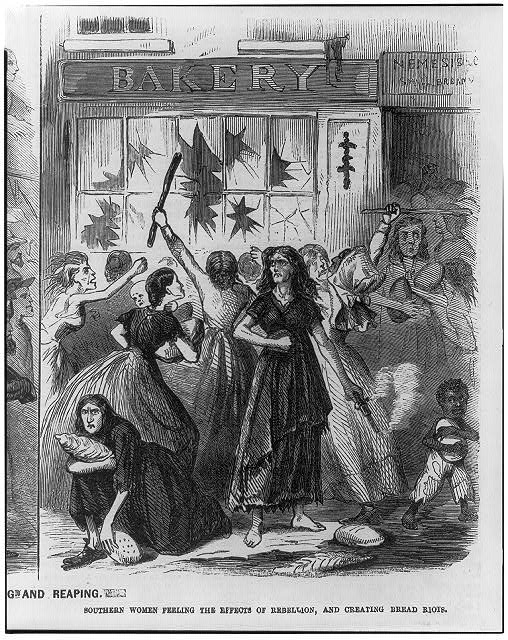

The economy went into meltdown, and inflation spiralled out of control. Even the most basic of foodstuffs became virtually impossible to obtain. When they were available, buyers could expect to pay $1,500 for flour, $12-$15 and $20 per pound for beef and butter, respectively.

Boots sold for $500 a pair. Neither soldiers nor their families could hope to acquire new boots at this price, so the troops had to make do. They repaired their old boots as best they could. When repairs were no longer possible, the ‘lucky’ ones acquired new, to them, boots from dead soldiers. The less fortunate were reduced to tying rags on their feet to protect and keep them warm. It was a disheartening sight for the officers to come across bloody footprints in the snow where their men had been patrolling.

With prices skyrocketing, Southerners had little choice but to live as frugally as possible. Meat was a rare commodity as farm animals had either been commandeered by the military or already eaten by the families. An average meal consisted of cornbread dunked in bacon drippings, dried beans, and a concoction of brewed roasted chicory, acorns, yams and a variety of local grains, which passed for coffee.

Mrs. William A. Simmons, whose husband was serving in the trenches, summed up the situation succinctly in a diary entry dated 23 March 1865: ‘Close times in this beleaguered city. You can carry your money in your market basket and bring home your provisions in your purse.'

A foreign businessman who had dealings in Richmond transferred his paper money to coined currency on the advice of his banker as Confederate legal tender was virtually worthless.

Petersburg Under Siege

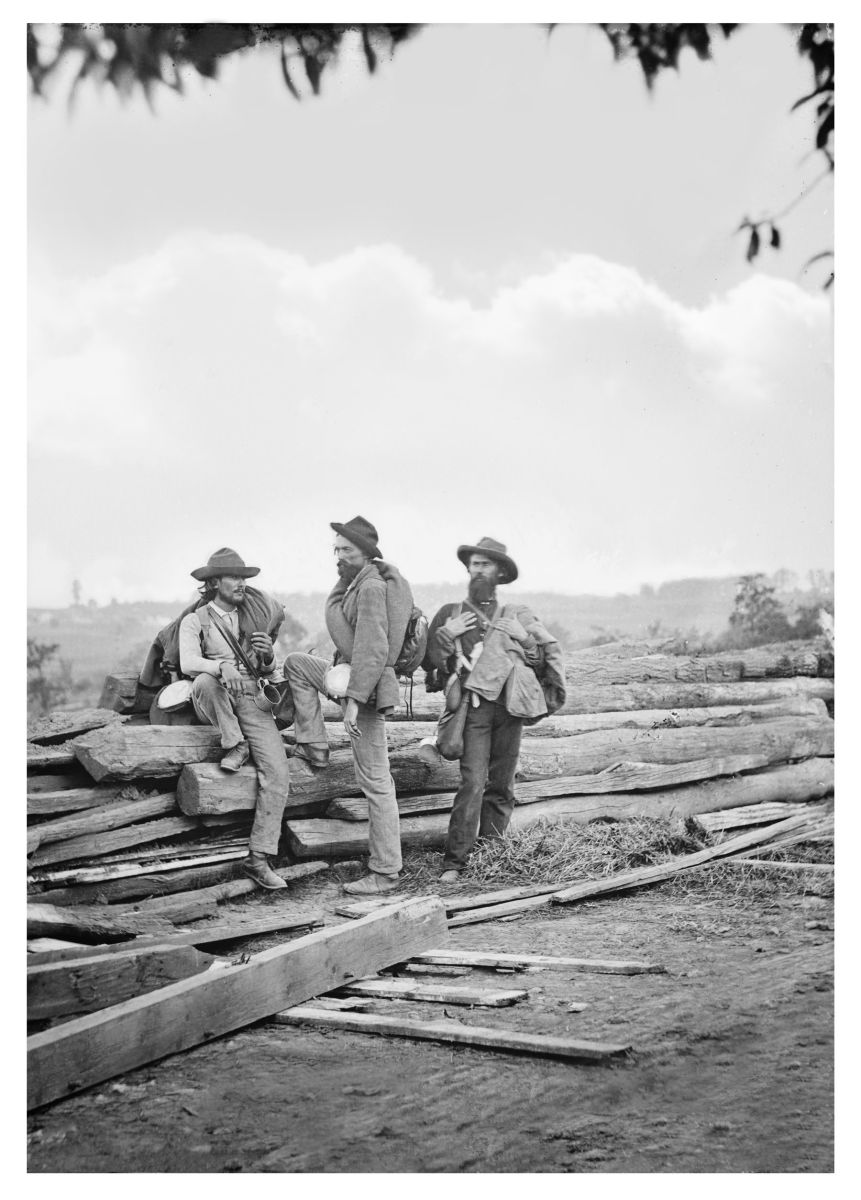

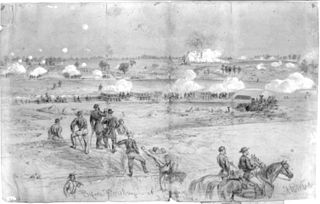

Richmond had long been a valued prize for the Union forces, but she proved difficult to capture. The Confederate government had allocated a significant portion of men and resources to ensure the capital would not fall into Union hands. After failing to take her during the Overland Campaign (4 May-12 June 1864), Union General Ulysses S. Grant changed tactics and headed for Petersburg.

Petersburg’s many railroads were critical in bringing supplies to Richmond and to Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Capturing Petersburg and her railroads would further debilitate Richmond and force General Lee to either relinquish her or meet General Grant on open ground.

For nearly a year, General Grant laid siege to Petersburg and General Lee’s army. Despite the bitter fighting in the trenches surrounding Petersburg, the Confederate army successfully rebuffed all Union attempts to cut the rail lines and capture Petersburg.

However, by March 1865, desertion, illness and injury had severely weakened General Lee’s army leaving him with only 44,000 exhausted, hungry men and no hope of getting fresh recruits or supplies. Against General Grant’s 128,000 better fed and better-equipped soldiers, it was a matter of when not if, the Northern forces would break through. Still Richmond, and indeed most of the South, believed that General Lee and the Confederate army would never let their capital fall.

Fleeing Richmond

As March wore on, many citizens, fearing the worst, made ready to flee Richmond. Red flags appeared outside houses indicating furniture for sale and houses to rent. Though whom they hoped to sell to at a time when money was scarce, I cannot imagine.

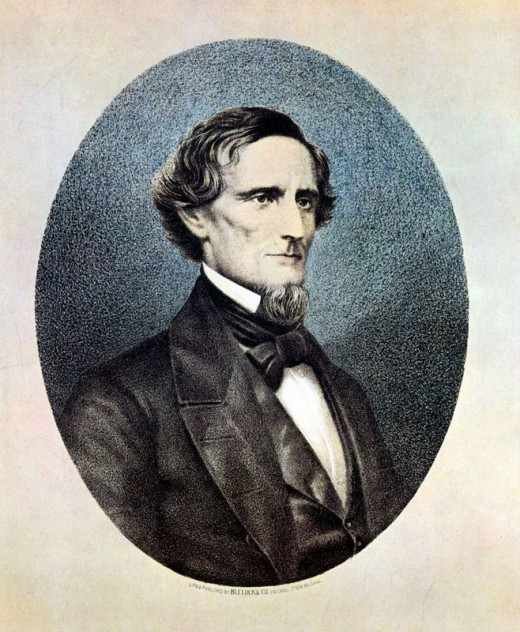

Confederate President Jefferson Davis had also begun preparations to move his family to Charlotte, North Carolina. He gave his wife, Varina, a pistol and showed her how to use it. If the worst should happen, he instructed her to take the family to the Florida coast and to board a ship to another country if they could find no safe refuge.

The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down

On Sunday, 2 April 1865, while President Davis attended church services, he received a telegram. It was from General Lee informing him the Northern troops had broken through the lines around Petersburg. He also advised the defence of Richmond was no longer possible, and she would have to be abandoned.

President Davis and his aides left the church during the service. As they walked briskly up the aisle towards the exit, a ripple of whispers followed in their wake. Once outside, he ordered the immediate evacuation of the government from Richmond and a new capital be set up in Danville, Virginia. President Davis then went home to inform his family they would be leaving.

The evacuation would not be announced officially to the public for hours. However, they could not help but notice government employees feeding countless documents about the war effort to fires outside government offices. Rumours began to circulate among the concerned citizenry. Officials neither confirmed nor denied any of them, though one insider did acknowledge the fighting near Petersburg and hinted the government would most likely be gone within 24 hours.

By 4 o'clock that afternoon, formal word of the government's departure was announced. Chaos ensued. For the rest of the afternoon and all through the night, officials and prominent citizens packed what they could and employed all manner of conveyances to hasten their escape from Richmond.

Through it all, President Davis did not give up hope. Up until the last minute, he expected, prayed for another telegram from General Lee informing him the tide had turned and Richmond was safe. It never arrived.

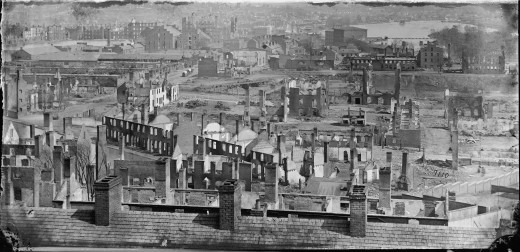

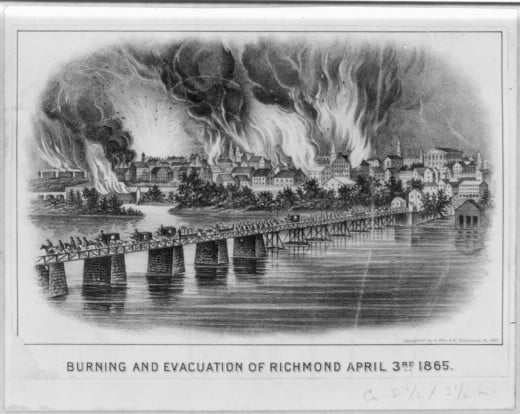

In the meantime, the remaining Confederate soldiers burned what they could to keep Southern assets out of enemy hands. They threw tea, cotton and still more government documents into the numerous fires dotting the city. As they burned, the winds spread the embers which then came to rest on surrounding structures. Soon the business district was alight.

Adding to the horror of this surreal nightmare were the sounds of explosions. The Tredegar Iron Works had been set ablaze setting off the loaded shells stored there. Mild frenzy escalated into outright panic.

A column of black smoke soon rose near the railroad station as ironclads, steam-propelled warships fitted with iron armour, were consumed by flames. When the ships' munitions exploded, windows as far as two miles away were blown out, tombstones overturned and doors torn from their hinges. The people forced to stay behind were nearly out of their minds with terror.

As the last of the troops rode out to join General Lee, those they left behind believed the soldiers would yet return to protect Richmond.

Early the next morning, soldiers did indeed come marching into the city. However, they wore not the homespun cloth of the Confederate uniform, but the navy blue of the conquering Union troops.

The Fourth Massachusetts Cavalry raised two guidons from the capital building. Instead of the stars and bars of the Confederacy, the traumatised denizens now looked upon the stars and stripes of the United States.

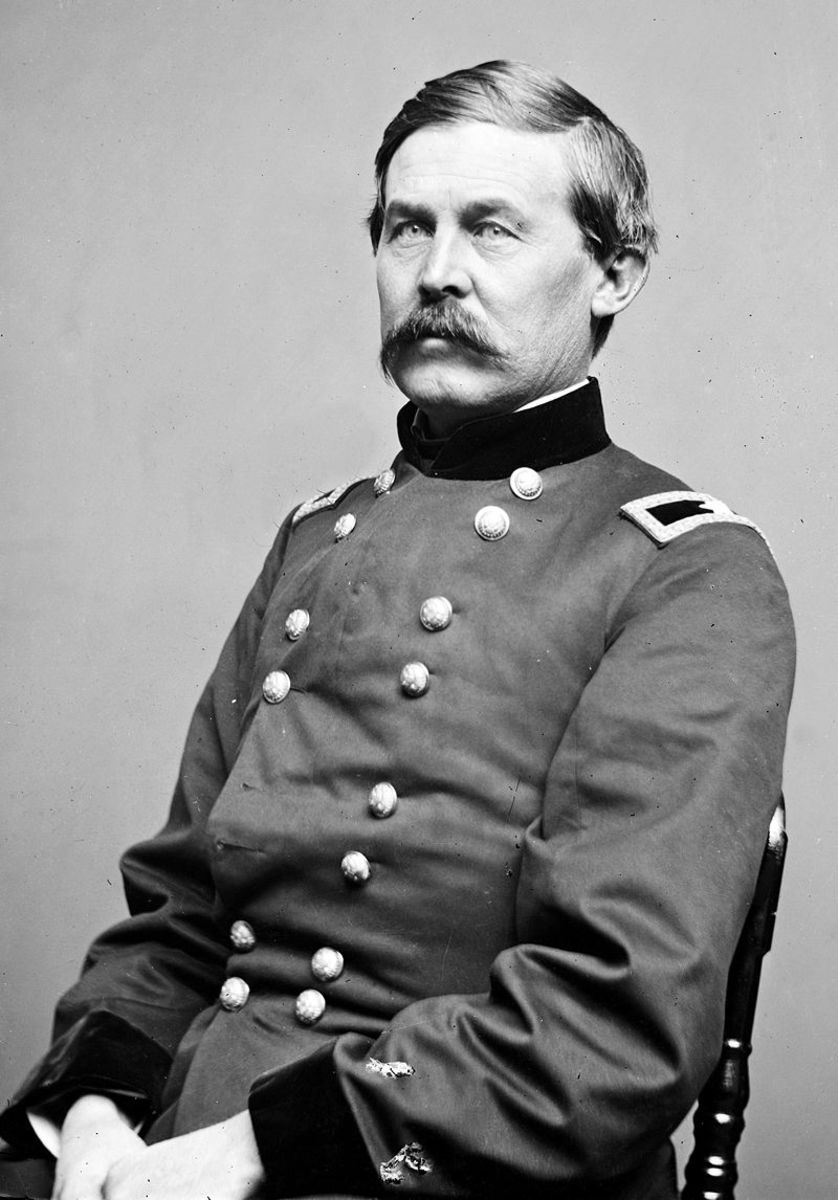

Shortly after their arrival, Union General Godfrey Weitzel sent a telegram to General Grant informing him that Richmond was theirs.

After the Fall

General Weitzel's first task was to restore order. Fires still burned in the city and he instructed his troops to put them out. Fortunately, the city's two fire engines were still in working order. Bucket brigades were organized, unsafe buildings were knocked down and used as firebreaks to help prevent the fires from spreading further. It was an arduous task as the winds still fanned the flames. After five long hours, the winds finally shifted, and the Union troops were able to bring the conflagration under control.

It is a bittersweet irony that the grand dame of the South had nearly been destroyed by those who had sworn to protect her, yet had been rescued by those who had sought to bring her to her knees.