- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas

With The Old Breed: Debunking the Myth of World War II As The "Good War."

"They answered the call to help save the world from the two most powerful and ruthless military machines ever assembled, instruments of conquest in the hands of fascist maniacs." (Tom Brokaw -XIX)

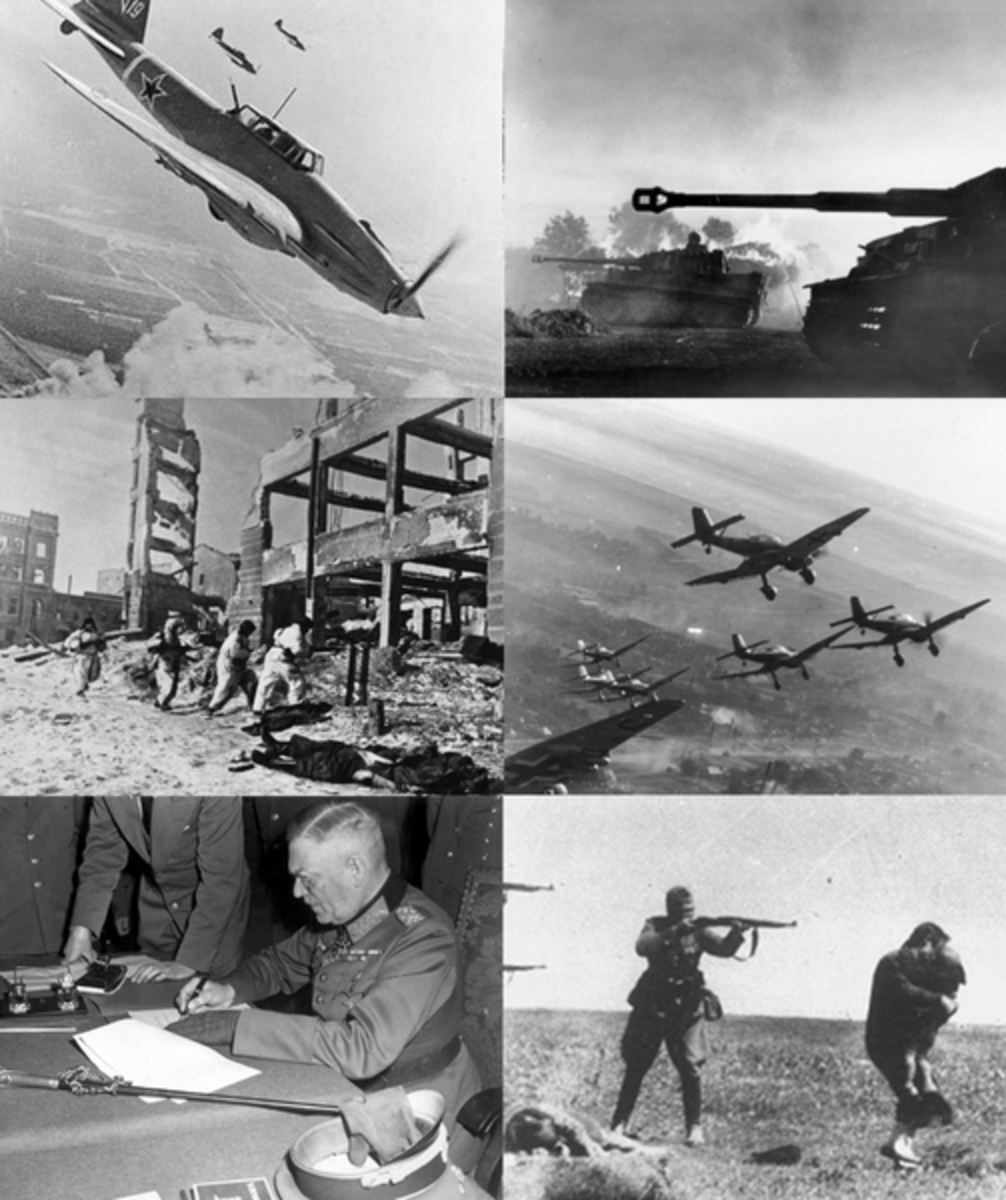

Like any other war in history, World War II was fought on battlefields stained by the blood of the countless combatants who lost their lives on both sides of the conflict. It was waged under total war; in-numerous soldiers and civilians alike lost their lives under newly created mechanized machines of death. But, because the reality of World War II was so resoundingly horrific, many Americans remember the war on more just grounds, labeling it the "good war." However, in recent times, authors have attempted to debunk this myth of the “good war,” in hopes of showing that no good comes from armed conflict.

While most authors attempt to debunk this myth in hindsight to effectively rewrite history, one soldier, before his experiences in World War II even began, realized the need to label this war what it truly was. Drawing on the idea that very few accounts had ever given the true nature of war, Eugene B. Sledge, a United States Marine, would record his unaltered experiences in his diary during and after his battles. This account, which would later form itself into the novel With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa, tells World War II as it was – real, personal, and horrific. Sledge’s novel, the personal and unedited account of a frontline soldier in World War II, in its fearlessness of including that which most memoirs do not, offers a new type of memory rarely seen before its time. Its personal and visceral events and tones, on a large scale, extend themes which fundamentally debunk the myth of the “good war,” even before such a myth had been publicly “remembered.” Therefore, it is not subject to altercation by the throws of the “good war” myth.

To begin, the myth of the “good war”, which many do not consciously realize exists, must be analyzed. Obviously, the past is remembered by those who lived it. While this remembrance may be correct, it does however, contain elements of storytelling, and/or modification. These factors, combined with the possible lack of certain events, ultimately create a memory, however false or correct it may be. From these memories, histories are written, in which key events are passed down. These combined memories and histories can come together to form what is known as the public memory - the collective remembrance by an entire people or country. As one critic of the “good war” myth explains, “To make our understanding of history manageable, we try to retrieve from the huge clutter of the past only those events that seem to be particularly useful, interesting, or exciting. (Adams-1) And in the case of the “good war,” the righteous public memory is usually that of the victors – the United States. As opposed to the war being remembered as hard fought and bloody, and its cause for that of land and resources, it is simply idealized as a true fight between good and evil; the dual of freedom and democracy over tyranny.

During the early anniversaries of World War II, when interest in the subject peaked, many authors began to think critically of this myth. Was it true? Were American truly fighting the personification of evil in a just and good war? Historical critics, namely Studs Terkel and Michael C.C. Adams, have attempted to rewrite the history of the second world war and effectively alter public memory. Through the use of interviews, these authors have sought to relay to the public that World War II was anything but good - quite the opposite in fact. But, in using interviews of those involved in World War II which were taken anywhere from forty to fifty years after the war, have not these testimonials and those who gave them been subject to the throws of the myth of the “good war”? For remember, memory exists only in the mind of those who experienced the war, and is therefore subject to any stimuli received since its creation. Therefore, these accounts may be void of true emotion, feeling, or even fact. This is where the importance of Eugene Sledge’s testimonial comes into play.

Like Terkel and Adams, Sledge was unsatisfied with wartime accounts absent of reality and personal emotion. But, unlike these two authors, Sledge was dissatisfied even before the war began. Sledge relays to readers that in growing up, “My parents taught me the value of history. Both my grandfathers were in the Confederate Army. They didn’t talk about the glory of war. They talked about how terrible it was.” (Terkel-65) But in actually looking for straightforward written accounts, the kind which history relies upon most, Sledge could find none. “In all my reading about the Civil War, I never read about how the troops felt and what it was like from day to day…During my third day overseas, I thought I should write all this down….” (Terkel-65)

In hearing of the death, decay, and horrific nature of the Civil War, juxtaposed with various memoirs and writings altered through memory, Sledge saw an obvious difference. Just as World War II has taken on its “good war” aspect, the Civil War took on a vastly different public memory than remembered by frontline soldiers. As one expert proclaims “At its outset, the Civil War triggered romantic impulses…Ultimately, however, the war produced death and destruction on a massive scale…” (Binder-271) From this, Eugene decided to record a real and uncensored account of his frontline experiences; an account filled with the realities of death, the screeching of artillery, and the horrific stench of battle. “Most memoirs (with rare exceptions) stopped short of ‘telling it like it was.’ I simply wanted my family to know exactly what the price of freedom is.” (Sledge-2) But, in the end, what makes Sledge’s account so important in the debunking of the “good war” myth?

Unlike interviews found in more recent novels, Sledge’s account was experienced, and within hours and days, transferred directly to his Gideon’s New Testament Bible which he carried with him (troops, especially in the Pacific, were encouraged not to record their day-to-day experiences) (Sledge-xiii). Because authors now rely upon testimonies taken decades after World War II, such accounts may be subject to the “good war” myth, and cannot be taken at face value. Sledge, before the war even began, however, realized a need to tell his story, the story of a frontline soldier in the most explicit detail as possible. Sledge’s verbatim-like tone gives the reader the feeling that they are there; that these events happened yesterday. This feeling combined with his emotions at the time, offer a truly unheard of account – an account unaltered by the “good war” myth. And in doing so, Sledge undoubtedly shows how the “good war” was anything but good.

Sledge begins his novel just as he began his wartime experience – with basic training. Put under the riggers of exercise, combat training, and weapons practice, Sledge was on his way to becoming a genuine Marine. It is here that he first begins to show readers why World War II cannot be labeled good. “Don’t hesitate to fight the Japs dirty,” one veteran drill instructor proclaimed to Sledge and his unit. “Kick him in the balls before he kicks you in yours.” (Sledge-18) From this point, Sledge, like the reader, begins to see that the fighting between the Japanese and Allies would be anything remotely civilized.

From basic training, Sledge is shipped out to the island of Pavuvu, where his battalion awaits the call of battle. Amidst the boring training, drills, and Bob Hope visits (Sledge-34), Sledge’s battalion is eventually given their orders – to take the small island of Peleliu. On September 15th, 1944, Sledge and his battalion hit the beach under heavy fire from the Japanese. Experiencing shelling and machine gun fire, Sledge began to experience his first feelings of battle. On the beach, Sledge witnessed the destruction of an amphibious landing craft with fellow marines still inside. As these men leapt from the flaming wreckage, they were cut down by machine gun fire. Sledge could only watch. “I shuddered and choked. A wild desperate feeling of anger, frustration, and pity gripped me…I felt sickened to the depths of my soul. I asked God, ‘Why, why, why?’” (Sledge-60) It is here that Sledge came to terms with the idea that in the randomness of war, anyone can be taken at anytime. Like Sledge, these dying men had lived for seventeen to eighteen years, gone through over a year of training, and had met their ends before they even touched the island’s edge - quite an appalling thought.

Amidst this chaos, Sledge and his unit finally make it off of the beach, where they encounter their first dead enemy. “The [Japanese] corpsman was on his back, his abdominal cavity laid bare. I stared in horror, shocked at the glistening viscera bespeckled with fine coral dust. This can’t have been a human being, I agonized.” (Sledge-63/64) During his first close-up encounter with a living enemy, however, involving the taking of a Japanese pillbox, Sledge felt the closeness of death. In peering his head over a small embankment, Sledge was met with the barrels of three Japanese rifles. Luckily, Sledge ducked in time, narrowly escaping death. “A million thoughts raced through my terrified mind: of how my folks had nearly lost their youngest, of what a stupid thing I had done…and of just how much I hated the enemy anyway.” (Sledge-114) In such emotional detail, Sledge truly shows the reader the overall inescapable feeling of death during this war. At nearly any time, anyone, no matter how confident or moral, could be taken at any second.

Next, Sledge reveals one of the more ever-present and nauseating battlefield traits, even devoting an entire section of the book to it – “The Stench of Battle.” In their shortcomings, several accounts and films regarding war only lend reality to sight or sound. Sledge’s account however, lends itself to one of the more horrific senses – the smell. Unable to bury bodies due to the hard coral earth, and under the intense sun “the dead became bloated and gave off a terrific stench within a few hours of death. It is difficult to convey to anyone who has not experienced it the ghastly horror of having your sense of smell saturated constantly with the putrid odor of rotting human flesh day after day, night after night.” (Sledge-142) Through this dire description, Sledge conveys horrific aspects of the battlefield other than sight or even sound; his direct accounts create a setting in the reader’s mind like no other account can.

After successfully taking the island of Peleliu, Sledge and his unit are shipped back to Pavuvu for a few months of rest and rehabilitation. It is easy to see, from just one battle, how erroneous it is for such a war to be labeled as “good.” This battle however, serves only as a precursor to the horrors Sledge would experience during his next battle – the Battle of Okinawa.

Already having landed, and enjoying a relatively simple invasion, Sledge is once again thrust back into war. In one of the rare instances of calm during Okinawa, Sledge takes in his surroundings. To his right he notices an endless row of dead comrades, covered under their ponchos, “a commonplace, albeit tragic, scene.” (Sledge-252) Further away however, Sledge noticed other dead Marines, not given the luxury of covering. “The bodies lay pathetically just as they had been killed, half submerged in muck and water, rusting weapons still in hand. Swarms of big flies hovered about them.” After reading this, one truly comes to terms with the number of dead, but also the horrific ways in which these bodies were treated. In times of peace, if a man died, he would be carefully laid to rest in a nice, clean church and casket. Yet here, in the “good war,” hundreds of dead bodies were rotting away in the warm rain just as garbage would.

Throughout the pages of his account, one can see that Sledge has not only experienced something completely terrifying, but has recorded it with great detail. Unequivocally, Sledge has done this by means of honest, unaltered descriptions; descriptions which strive to carry the shocking feeling felt by Sledge into the stomachs of the reader through the use of all senses. More importantly however, and unlike other testimonies, Sledge has given the thoughts and emotions experienced at the actual time of these events. Because this account was recorded immediately after these events, it contains detail no other account could. Accounts which are recorded several years after the events often times leave out such awful events and descriptions.

To truly show the difference between an on-the-spot recording versus belated interviewing, consider John Garcia's account of the Battle of Okinawa. While still shocking, Garcia’s account was taken nearly forty years after the battle, and therefore does not contain the feeling nor the descriptions that Sledge’s account offers. An infantryman in the United States Army, Garcia most likely experienced several of the same feelings and emotions as Sledge did. In the most horrific event in Garcia’s story, he mistakenly shoots an Okinawan woman – a civilian. “This one night I shot and when it came daylight, it was a woman there and a baby tied to her back. The bullet had all gone through her and out the baby's back.” (Terkel – 23) While outright gruesome in its own right, Garcia’s account is nevertheless devoid of his emotion at the time of the event. All that Garcia will relay is that the event haunts him. But, as one can see, the obvious pain caused by such an event prevents Garcia from relaying the full truth of his experience. It also lacks grisly detail; detail that Sledge otherwise would have included. This prevention of reality ultimately lacks the ability to debunk the “good war”myth; at least not with the same tenacity that Sledge’s novel does.

One of the more unparalleled dimensions of Sledge’s novel however, is its occasional and noted interjections by the author, right before the book’s publication in 1981. In it, he offers corrections and added military information without altering his original narrative. The most important of these interjections is the novel’s conclusion. Where the author’s narrative offers unintentional ideas of un-romanticized war, Sledge’s conclusion quite clearly lays out his opinion of the “good war.” “War is brutish, inglorious, and a terrible waste. Combat leaves an indelible mark on those who are forced to endure it.” (Sledge-315) And in a letter to a fan about the book’s publication, Sledge proclaims “What actually won the real war battles was bravery, discipline, training, and esprit de corps – the ‘cool headed’, big-man, tough stuff was strictly a product of Hollywood.” (Sledge-2) Such Hollywood cannon, the copious John Wayne movies, were one of the more obvious creators of the “good war” myth, and therefore demolishers of the truth.

In the end, Sledge gives readers an extremely honest novel which inexplicably debunks the “good war” myth, even before such a myth was created and remembered. Through horrific and deeply saddening events, characterized by simplistic tone and beautiful description, does Sledge offer a war that should never be called good. It is clear that Sledge has no boundaries; he has presented war as it happened, in all its gore. And because it was recorded at the time of the events, it encompasses exact feeling and emotion; emotions which are often times missing from other accounts due to the pain they cause. In the end, With the Old Breed leaves readers pondering the validity of the “good war.” If it truly was a “good war,” why were so many young men needlessly killed instantly and without warning, only to be left to rot? Why were such young men forced to cope with constant thoughts of death, and the smell which followed? Would not a “good war” dispense of such mayhem?

Matthew Gordon is the author of The Thin Blue Line: An In-Depth Look at the Policing Practices of the Los Angeles Police Department &

To Live, To Think, To Hope - Inspirational Quotes by Helen Keller.

© Matthew Gordon, 2011

Recommended Books:

Bibliography

· Adams, Michael C.C. "Mythmaking and the War." The Best War Ever. Baltimore: JohnsHopkins University Press, 1994. pp. 1-19.

· Binder, Frederick M. and David M. Reimers. The Way We Lived: Essays and Documents in American Social History. Vol. 1. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2008.

· Brokaw, Tom. "Prologue." The Greatest Generation. New York: Random House, 1998. pp. xviii-xx.

· Sledge, Eugene B. With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa. New York: Ballantine Books, 1981.

· Sledge, Eugene B. "Sledge letter to Eric Mailander, 7-6-1982." Eugene B. Sledge Collection. The Auburn University Digital Library, 1982. <http://content.lib.auburn.edu/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/ebsledge&CISOPTR=95&REC=15>.

· Sledge, Eugene B. "Sledge letter to George B. Clark, 3-16-1982." Eugene B. Sledge Collection. The Auburn University Digital Library, 1982. <http://content.lib.auburn.edu/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/ebsledge&CISOPTR=80&REC=10>.

· Terkel, Studs. “E.B. (Sledgehammer) Sledge.” The Good War: An Oral History of World War Two. New York: Pantheon, 1984. pp. 59-65.

· Terkel, Studs. “John Garcia.” The Good War: An Oral History of World War Two. NewYork: Pantheon, 1984. pp. 19-24.