Confabulation in Patients with Amnesia

Overview

Confabulation is ”a falsification of memory occurring in clear consciousness in association with an organically derived amnesia” (Berlyne). This typically happens when a certain memory retrieval process is provoked, most typically from being asked a question, and the retrieved memory is false. But it can also happen spontaneously where a person believes a memory is true and acts in relation to that memory. It is important to emphasise that there is no intent from the person producing confabulations to deceive the listener, he genuinely believes the memory is true and acts accordingly (Turner et. al.).

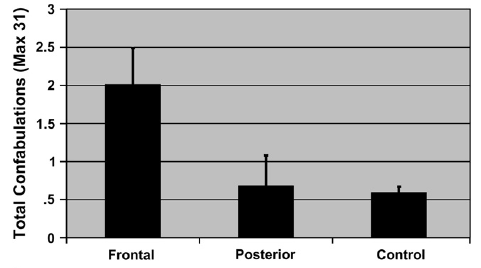

Research has shown that confabulation mostly occur in people with some sort of memory deficit. The people that have participated in experiments and produced confabulations have typically performed poorly on memory tests, suggesting that for confabulations to occur there must be some memory deficit present (Turner et. al.). Along with memory deficits, confabulation also seems to be connected with damage to the frontal lobe (Turner et. al.).

A good example of confabulation would be a case study by Baddeley and Wilson on the patient R.J. (Baddeley & Wilson). R.J. was a victim of a traffic accident where he got a severe head injury which left him unconscious for many weeks after the accident. He was studied by Baddeley and Wilson six months after the accident. R.J. was shown to be amnesic and had “bilateral frontal damage and a dysexecutive syndrome” (Baddeley & Wilson). When asked about the traffic accident he gave a very detailed but confusing explanation on how he overtook a lorry and got hit by a different lorry. He then proceeded on reciting his conversation with the driver of the lorry that hit him, which was highly repetitive:

“He stopped and I stopped and he said “I’m sorry mate” and I said “Don’t worry about it, it was as much my fault as yours” and he said “Well it was really”. So I said “Well there’s nothing much I can do about it”, so he said “Well there isn’t is there really” and I said “No, not really”, so he said, “Well what’s going to happen now?” I said “Well, as far as I’m concerned nothing will happen at all because it was my fault, or most of it was my fault”. He said “OK”, so I then said “Well, as far as you’re concerned there’s no need for you to do anything because it was my fault, or mostly my fault”. He said “Well, that’s fine”, he said it was and I said “Well yes it was indeed”, so he said “Are you going to do anything about it” and I said “No” and he said. . . . . ” “ (Baddeley & Wilson)

Given that R.J. was unconscious for several weeks after the accident his story of the whole accident would clearly be a confabulation. Baddeley and Wilson asked him about the accident several times and his accounts of it differed each time (Baddeley & Wilson).

Provoked versus spontaneous confabulations

Confabulations have two ways of occurring; provoked confabulations and spontaneous confabulations. Provoked confabulations arise when a person is forced to retrieve a memory, e.g. when a person that is asked about something in his past. This type of confabulation is the most common, and is the one most encountered in experiments and case studies. Spontaneous confabulations occurs without any external intervention by other people, i.e. a person who produces a confabulation might just act on a false memory, for example if they want to show someone something from their “past” (Kopelman). This makes it harder to research as it can not be shown in a lab environment, or through interviews with patients. Armin Schnider has shown that “spontaneous confabulation [can] be singled out as a distinct form of false memory after anterior limbic (in particular orbitofrontal) damage” (Schnider).

Why do confabulations occur?

According to Moscovitch and Melo there are two main components as to why confabulations occur; defects in memory retrieval (more specifically “Faulty output from the associative/cue-dependent retrieval system” and “Impaired strategic search processes”) and defective monitoring of retrieved memories (Moscovitch & Melo). Defects in memory retrieval are usually accounted for by amnesia, which is usually the case for people that produce confabulations. The frontal lobes play an important role in the memory retrieval process and they “act as 'working with memory' structures” (Moscovitch & Melo). More importantly, they are responsible for monitoring, evaluating and verifying the recovered memory traces (Moscovitch & Melo). A person with damage to the frontal lobes will therefore have no way of evaluating his retrieved memories, resulting in false memories being perceived as true.

An early hypothesis, which is still taught today, concerning confabulations is that people with amnesia produces confabulations to “fill in gaps” in their memory. In the example with R.J. for example, he would have had no memory of the accident, and therefore produced confabulations to make up for the missing memory. Experiments have shown that it is very unlikely that confabulations arise from a desire to “fill in gaps” in memory (Schnider et. al.).

For further reading

- The Truth about Confabulation: General article about confabulation.

- Confabulation: Damage to a specific inferior medial prefrontal system: Research article linking confabulation and damage to the frontal lobes.

References

Baddeley, A., & Wilson, B. (1988). Frontal amnesia and the dysexecutive syndrome. Brain and cognition, 7(2), 212-230.

Berlyne, N. (1972). Confabulation. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 120(554), 31-39.

Kopelman, M. D. (1987). Two types of confabulation. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 50(11), 1482-1487.

Moscovitch, M., & Melo, B. (1997). Strategic retrieval and the frontal lobes: evidence from confabulation and amnesia. Neuropsychologia.

Schnider, A. (2003). Spontaneous confabulation and the adaptation of thought to ongoing reality. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 4(8), 662-671.

Schnider, A., von Däniken, C., & Gutbrod, K. (1996). The mechanisms of spontaneous and provoked confabulations. Brain, 119(4), 1365-1375.

Turner, M. S., Cipolotti, L., Yousry, T. A., & Shallice, T. (2008). Confabulation: Damage to a specific inferior medial prefrontal system. Cortex, 44(6), 637-648.