Eliza "Do Little": Women's Roles and Representation in Broadway Musicals

Picture, for a moment, a Broadway stage. The curtain rises to reveal an Edwardian street corner: the opening scene of the iconic My Fair Lady. The audience guffaws at Eliza Doolittle’s classless antics, cringes at her accent, sighs in awe as she floats down the steps in her ball gown, and gleefully applauds when the show comes to a close. All file out of the theater with a sense of content in having seen a classic and quality piece of theatre except for, perhaps, the feminist who instead walks away with an odd taste in their mouth. Without a doubt, the Broadway musical is a staple of American entertainment. Broadway songs graced the radio waves for decades and with the new influx of musical movies, modern-day audiences are being introduced to the joys of a good musical number. Musicals can make their audiences laugh, cry, think, and possibly even change their perspective on the world, for they often reflect or are a reaction to the greater social context occurring just outside the theater doors, which is why the conclusion of My Fair Lady might leave some modern audiences scratching their heads. By the end of the show, Eliza has become an educated woman who can do anything with her life and instead returns to the man who treated her like a project more than like a person. Eliza, much like the female characters who would grace the stage after her, represents the ideal woman specific to the greater social context of the decade. Whether those images are progressive and empowering or suppressive and lackluster depends on the decade, as the image of women and their roles has constantly shifted on the stage.

The Early Years

American women did not begin to mobilize on a national scale until the 1880s and while the suffrage movement did not voluminously impact Broadway, its legacy left its mark in the occasional musical. Ziegfeld and his Follies were a far cry from feminist, but on one hand, his performances did present women the opportunity to make a living on their own. On the other hand, his women were essentially nothing more than extensions of the scenery: literally objectified, as they served as objects in a spectacular tableau. The Cinderella musicals of the 1920s provided a bit more substance for women in which a working-class girl is able to climb her way up the social ladder and is rewarded either with a man of her dreams or fame. Bypassing the fact that the woman’s “reward” is often times a man, these Cinderella musicals mirrored and encouraged real women to move up in society. The 1940s was host to at least one consciously feminist musical in Bloomer Girl, but it has sadly faded from the average theatre fan’s repertoire in favor of bigger musicals such as Annie Get Your Gun, which possesses a rather problematic plot in which the title character throws a contest and denies her own attributes in order to win the affection of a man.

Broadway's Golden Age

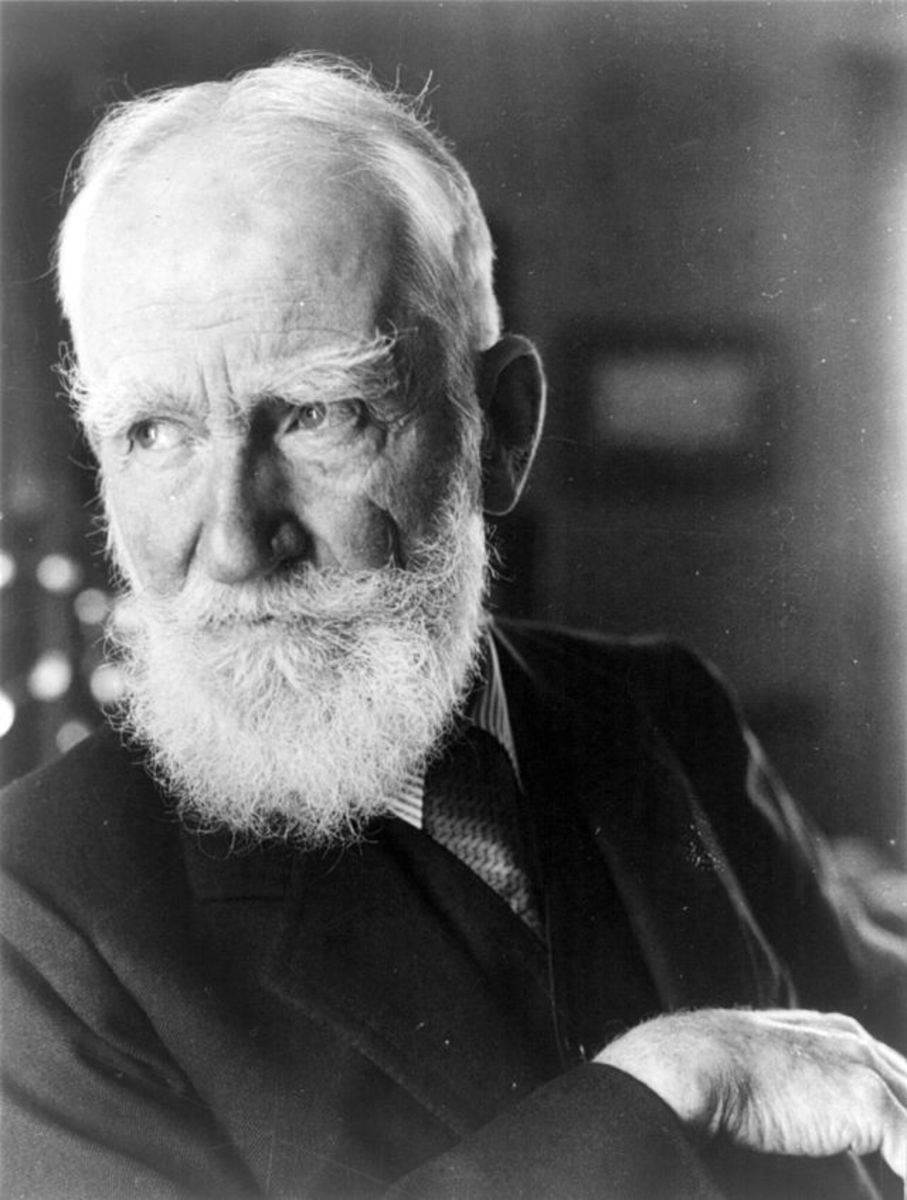

Women had found a niche in the workplace during the war, but the 1950s quickly re-established a woman’s place in the home. My Fair Lady is the shining example of a perfectly constructed musical that eventually outran Oklahoma! on the Great White Way. Its stunning songs and dazzling costumes no doubt kept audiences clamoring for a seat, but its ending is all too troubling from a feminist perspective. Eliza, as a working-class woman, represents the women of the Second World War who set down their rolling pins in favor of a riveter. Eliza is boisterous, uncouth, and everything a woman of the 1950s should not embody. Higgins then enters the picture and attempts to transform her, forcibly softening her to become more feminine to the point where he drives her to tears. His attempts are eventually successful and he immediately prepares to showcase his new, idealized woman. It is not until the morning after the ball, as Higgins congratulates everyone but Eliza on a job well done when Eliza finally realizes she has been used. The audience is given a brief glimmer of hope when she leaves, presumably to go make something of herself with her newfound elegance only to return to Higgins in the closing scene. Upon hearing her voice, Higgins avoids her gaze and barks, “Where the devil are my slippers” instead of turning and offering her the wildly radical gift of an apology for treating her as less than he should have treated her. Granted, it would be immensely out of character for Higgins to do such a thing, but that is exactly the reason why the final scene is so problematic. Higgins is, to put it simply, a displeasing person and exhaustingly unapologetic of his actions. One cannot fault Eliza for returning to him if one wishes to interpret her actions as love for him, but considering George Bernard Shaw wrote an entire preface to Pygmalion explaining why Eliza and Higgins should never be romantically involved under any circumstances, such an interpretation becomes something cringe-worthy to fans of the original play. The mere suggestion that Higgins and Eliza might grow to be romantically involved is an affront to the original work and, as popular as My Fair Lady may be, it possesses an ending that will have feminists reeling and Shaw perpetually rolling in his grave.

The Second Wave Hits the Great White Way

The 1960s launched the women’s liberation movement into the spotlight, gaining victories for women's legal cultural, and social rights such as when the Food and Drug Administration approved the birth control pill in 1961. Betty Friedan's book, The Feminine Mystique, inspired many women to take charge of their own bodies. And yet along with this new liberated view on sexuality, a double standard continued to persist that forced women to be pigeonholed as either pure or -- well -- not so much. Naturally, women’s representations in musicals reflected such a dichotomy by showing women either as agents of their own lives or punishing them for being too assertive or sexually active. Musicals like Sweet Charity and Cabaret focus on women who take control of their bodies while simultaneously showcasing the “single girl” fantasy of a woman free from societal constraints that permeated the decade. The heroines of Sweet Charity and Cabaret are far from chaste, yet their overt sexuality is celebrated on stage. Both characters are shown to overcome their obstacles and carry on despite being deprived of a successful romance conventional to musicals of the previous decade.

But then, on the opposite spectrum are characters such as Aldonza or Nancy in Man of La Mancha and Oliver!, respectively. If Charity Hope Valentine and Sally Bowles represent the celebration of the sexually free single girl, Aldonza and Nancy are incarnations of the double standard. Nancy, a lady of the night, is trapped in an abusive relationship with the sinister Bill Sykes, yet she laments that she will stay loyal to him as long as he needs her. Where Sally and Charity are lauded for their autonomy, Nancy is punished and given little agency over her own body. When she finally takes initiative and tries to protect the titular character of the play, she pays the ultimate price when she is murdered by her boyfriend.

Aldonza is, both within the context of the story and theatrically, an object to be acted upon by the men around her. She is introduced and described in relation to her body: an unappealing woman that stands in sharp contrast to the pure, virginal vision of Dulcinea that Don Quixote sees in her place. Throughout the course of the play, her rough identity is reinvented and molded by Don Quixote (much like Eliza by Higgins) until she eventually softens and becomes more feminine. Most troubling, though, is her infamously brutal assault scene, which is treated as more of an excuse for Don Quixote to swoop in and be her hero, a notion supported by the music in the scene, which stays primarily in major keys that highlight Quixote’s heroic valor rather than Aldonza’s brutal victimization.

Aldonza's Self-Deprecating Song

Various civil rights movements had entered the mainstream by the 1970s, harbingering in a new trend of Broadway musicals such as A Chorus Line and Company that presented an ensemble of women and men operating in a community or group that contributed equally to the musical’s plot and theme. Although Company’s central character is a man with very masculine problems; the women of the ensemble play an equally important role as the men. The musical’s theme deals with marriage, and the characters offer a varying range of perspectives on the subject that are far from an idealized vision of a whirlwind romance. A Chorus Line features the same ensemble dynamic and gives both women and men an equal share of songs, but neither musical can be considered feminist. Musicals that were more conscious of the women’s liberation movement such as I’m Getting my Act Together and Taking it On the Road or Mod Donna were not as successful and in the case of the latter, reviewers tore it to shreds and used the occasion to taunt the feminist movement. Except for the avid Broadway-junkie, such musicals have been forgotten and with the influx of mega-musicals in the next decade, quietly slipped into the background.

Conservative Backlash

The 1980s saw a shift toward conservatism: a direct reaction to the civil rights movements that had occupied America's social atmosphere for the last two decades. Legal victories obtained by these groups were whittled down throughout the decade with a purpose that seemed to suggest that every form of discrimination had been eradicated. Musicals of the 1980s reflected such a sentiment and delivered non-threatening female roles that ignored the progress feminists had made in the last decade. Besides being a time of attempting to ignore that pesky thing called feminism ever happened, the 1980s was also a time of a second British Invasion of sorts in which Broadway was overrun by mega musicals from overseas. Les Miserables and Phantom of the Opera both offered audiences the same passive and waifish characters that must have delighted audience members who were sick of the strong, independent woman type of heroine. Both musicals re-established the stereotypical binaries of an active man and passive woman. The men of these musicals function in the world while the women are regulated to a domestic space. The men are artists and politicians whereas women are their muses. Traditional gender binaries return with these two musicals, as does the dichotomy between the pure and un-pure types present in musicals of the 1960s.

The women of Les Miserables are supporting characters with sparse activity in the musical’s plot. Fantine is punished for her sexuality, and while the musical treats her misfortune as a terrible act of fate, she dies within the first twenty minutes of the musical and her character serves more as a catalyst to motivate the male protagonist rather than having any real agency of her own. Even most of the songs the women sing are about the men in their lives. Eponine’s motivation and character arc does not grow further than her love of Marius and every song given to her is devoted to how much she pines after him. Cosette’s character has very little to do throughout the show and she serves the sole purpose of playing the perfect ingénue who falls in love with one of the many male protagonists. Out of all the featured women in Les Miserables, Cosette is arguably the one who suffers the most from a lack of characterization due to her lack of a true solo: the song ‘In My Life’ is a duet with Marius while ‘A Heart Full of Love’ is a trio with Marius and Eponine.

Despite her large amount of solos and stage time, Christine in Phantom of the Opera plays a similar role to Cosette in that both are portrayed as the stereotypical ingénue that acts as the male protagonist's muse. Any woman who does not fit neatly into the ingénue or virginal role is portrayed as cartoonish or is aptly punished for their boldness. Carlotta, the boisterous diva is an object of ridicule and comic relief in the drama and her strong-willed persona and powerhouse of a voice are forced aside in favor of the meek Christine who can hardly squeak out the first note when she is initially asked to sing for the new house managers. Similarly, the brash Madame Thenardier of Les Miserables is painted to be an unsavory caricature of a woman who, interestingly, also devotes a large portion of her solo time singing about a man, in this case her husband. One could make the argument that most of the characters of Phantom are equally vapid and one-dimensional as Christine regardless of gender. The musical offers a myriad of stunning visuals that are, perhaps, at the cost of believable characters. The only role with some substance is arguably Madame Giry considering she actually accomplishes things that drive and aid the plot. She appears to be one of the few characters in Phantom to possess any sense of level-headedness as opposed to the two befuddled house managers. While she is an enjoyable character to watch, her issues lie in the fact that she is an unjustly small role. Stacy Wolf, author of Changed for Good: A Feminist History of the Broadway Musical, brings up the point that the historical settings of both musicals create a logical excuse for women not to do much, but in the context of a show where the characters are singing throughout the entire action, one would hope that the suspension of disbelief would not come crashing down due to the presence of a woman in the front lines of the 1832 French revolution. The largest issue Wolf points out about these two musicals is that the representation of these women is retrograde and any actions in these shows for a woman are purely emotional and, further, on one emotional level. The women in Les Miserables grieve for and pine after men while Christine alternates between loving Raoul and fearing the Phantom, all while singing at the same intense emotional level that could bring down a house.

In today’s age, Third Wave feminism is beginning to blossom and with it, a new type of musical that emphasizes individuality such as the popular and wildly successful Wicked. The “untold story of the witches of Oz” and its focus on women’s relationships with other women has perhaps heralded in a new era of feminist musicals that have hopefully brought the reign of characters such as Eliza and Christine to an end.

Referenced Works

- O’Neill, William L. Feminism in America: A History. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1989.

- Ryan, Barbara. Feminism and the Women’s Movement: Dynamics of Change in Social Movement Ideology and Activism. New York: Routledge, 1992.

- Shaw, George Bernard. Pygmalion. The Norton Anthology of Drama: Volume Two. Edited by Peter Simon. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2009.

- Wolf, Stacy. Changed for Good: A Feminist History of the Broadway Musical. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.