Night of the Living Dead: Re-living the Undead

Introduction

Thanks to satomko for his article on Night of the Living Dead, which inspired me to do one myself.

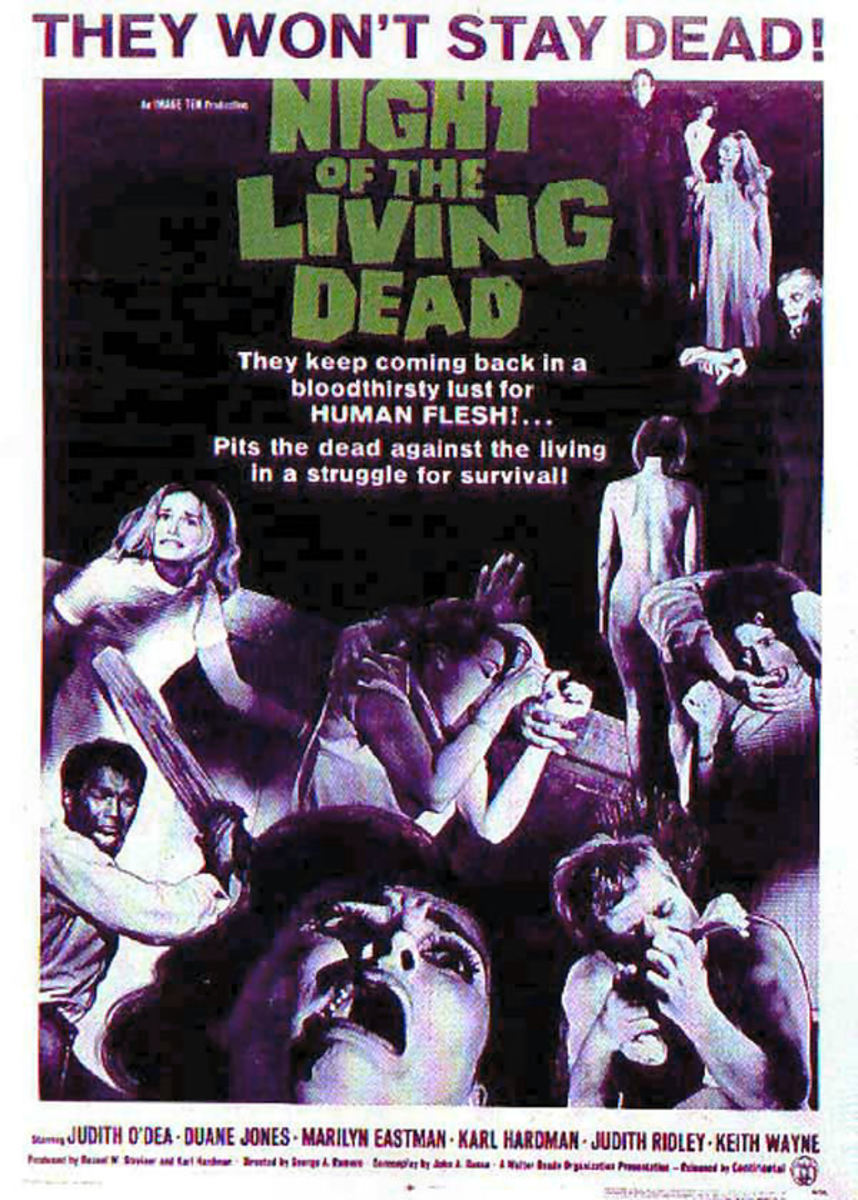

In case you're not familiar, Night of the Living Dead is the first in a series of horror films directed by George Romero that basically invented the zombie in motion pictures. The series contains Night of the Living Dead (1968), Dawn of the Dead (1978) (not the remake), Day of the Dead (1985), Land of the Dead (2005), Diary of the Dead (2007), and Survival of the Dead (2009). He was also the original writer and director of The Crazies in 1973, before it was remade earlier this year.

The following article is about how Night of the Living Dead is not just a cheapo independent horror flick; there's some very interesting social commentary going on that makes it quite unlike any other horror movie I've ever seen. Beware, this article contains SPOILERS, and you should definitely see the movie beforehand if you don't want the plot ruined for you.

Night of the Living Dead

George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) was a revolution in the genre of horror for several reasons. For one, it was the first to take material commonly associated with the exploitation movement (cheap special effects, independent production, sci-fi subject matter) and cast it in a more realist light. There were no heroes or villains, no grand solution to an impossible problem—instead there were only people, each one of them struggling to ‘survive’ in their own way. Even the supposed monsters garner our sympathies with their pathetic expressions of desperation and their inability to resist the urge to kill and feed. The realism gives the unbelievable and horrific events a refreshing ‘down-to-earth’ quality that makes the characters and settings more relatable to viewers, who were also struggling with violent world changes and horrifying possibilities in their own lives. To increase possibilities for identification with the subject matter even further, the subtly political themes of the film can be interpreted in many ways. One thing is for sure—the film captures/represents a fear of violence that is very much a presence in 1968, with the Vietnam War and race riots on everyone’s minds. Because Night was produced independently of Hollywood studios, the team of filmmakers behind it was able to reject many of the conventions of the horror genre and moviemaking in general, and instead make a film that had an incredible appeal to a youth market and a counterculture that were hungry for something more ‘real’: in both the sense of style of filmmaking and relevance to the cultural milieu.

The opening of Night of the Living Dead seems somewhat typical among exploitation horror films, but the genre bending in favor of realism becomes more and more apparent as the film goes on. There are a few things in the opening that cue us in to the unique nature of the film. The first encounter with a ghoul (they weren’t called zombies once in the entire film, Dawn of the Dead was the first official 'zombie' movie) introduces the possibility that the ‘monsters’ of this film are seemingly normal Americans, with no particular physical features that distinguish ‘them’ from the rest of ‘us’. Initially it is just the one ghoul that attacks Barbra, but soon enough more appear, and the latent fears of a generation are realized: the so-called enemy is living right here at home—and if you’re not careful you could become one. Night of the Living Dead was one of the first horror films to present Americans as a threat to other Americans (before, there was man vs. alien, monster, machine, etc). The terror in this notion is not limited to the fighting between man and homegrown zombie, but fighting between characters with their supposed humanity intact as well.

Consider, for example, the character of Harry Cooper and his relationship with the younger, educated, black hero, Ben. The threat of being eaten alive (literally) faces both of them, and yet they are unable to cooperate, instead bickering over whether to hide in the cellar or remain in the house. Neither of the two parties is necessarily right or wrong; we have no perfect hero to praise and no absolute villain to despise. The two characters represent conflicting ideals: “Harry aspires to the role of 1950s patriarch”, while Ben stands in for the youth movement and counterculture (Hervey 64). This aspect of the conflict provides a direct correlation to the real-life conflict of the moviegoers, many of whom, like Ben, were young progressives fighting against the ideals of the patriarchal nuclear family that Harry represents. This group’s fears are ultimately realized when Ben is proven wrong again and again and eventually dies, leaving them wondering if things are really so hopeless.

This fear of hopelessness is no drawback to the film but an enhancement. Until Night of the Living Dead, young viewers were hard-pressed to find a film that was true to life in its representation of their hopelessness. Many sci-fi, horror, and exploitation films ended happily, observing the Hollywood tradition of a successful hero and a saved world by the film’s closing credits. But Night’s independent production background allowed for it to take a stand against these traditions and provide something more current and relevant to its viewers. Attack on tradition is hinted at in the opening, with Johnny’s death following his impression of Boris Karloff. The Gothic, expressionistic look and feel of classic 1930s horror that Boris was part of is left completely in the dust; the dark and shadowy castles of fantasy replaced by the strikingly familiar setting of a family home. When Barbra first enters the house, we can see the expressionistic shadows of railings imprisoning her, but these disappear with Ben’s simple act of turning on the lights. Realism triumphs over the hyper-stylized and melodramatic in the world of Night of the Living Dead, allowing viewers to more easily identify with the subject matter.

One point on which it seems Night has failed to break with Hollywood is the explanation for the crisis: radiation falling to the earth from space. The film seems to have taken us back to Harry’s world—the world of the 1950s, where every threat was either alien or a radioactive mutant. The difference between the cheesy sci-fi horror B-movies of the 1950s and Night is in the presentation of this explanation. When the television news coverage shows us the general and the scientist discussing the Venus probe as an explanation, they can’t seem to agree, let alone propose a solution to the problem based on the information they have. Scientific and military power is of little to no use to the characters in Night; important officials are having just as much trouble cooperating as they are. The sense of hopelessness that the film is imbued with appears again here, and the worry that American officials spend too much time assigning blame, bickering, and hiding from the problem rather than trying to solve it. The fear of radiation is present in Night, but it is secondary to the current generation’s fears of threats primarily American.

The aggression of young Americans in 1968 was not aimed at a foreign threat, not even the one they were currently at war with in Vietnam, but rather the domestic government that was continuously threatening to draft them and send them to their deaths for reasons they disagreed with. And when they were finally given an opportunity to voice their opinions and escape the torment of this constant overbearing threat, they were overruled by what Nixon later called the ‘Silent Majority’. Hervey puts it this way: “The late 1960s saw an energetic, committed youth demand a new kind of America, only to be overwhelmed at the polls by the sheer numbers of the passively conservative; by the dead weight of past traditions that refused to be buried and returned to devour the future” (59). This quote equates the undead threat in Night with the Silent Majority, as they seemingly have no purpose in existing other than to undermine and destroy the human characters. But there’s ambiguity in this political interpretation: the violent, revolutionary ghouls tear down the walls of the 1950s style farmhouse, destroying the representation of the ideals that the counterculture would love to destroy. Whether the viewers choose to identify with the destructive ghouls or the threatened humans, one thing remains unambiguous; they are still fighting a war at home, Americans against Americans.

Besides the cultural war that was going on in America over Vietnam, there was a battle even more rooted in American soil: the one over civil rights. The fact that Ben, the young hero of the film, is black is hard to ignore, even though the filmmakers consider it a coincidence. The cooperative filmmaking behind Ben’s character led him to become an amalgamation of two different generations of black characters on screen: the hyper-masculine, active hero of blaxploitation films soon to come, and the passive, educated character often portrayed by Sidney Poitier. Ben is intelligent, a survivor, but also willing to pick a fight, sometimes for disagreeable reasons. His conflict with Harry signifies the real-world conflict over civil rights: Ben desires (and takes by violent force) the freedom to stay in the main house, to make important decisions, and to be the leader of his fellow survivors. But, this proves to be an unsuccessful strategy for Ben, as he and all of his companions end up dead. Ben himself is shot by a man mistaking him for one of the ghouls. The men who take it upon themselves to finally shoot Ben identify him as “other,” in this case a ghoul, and therefore feel threatened by him. This identification as “other” is a source of racial tension, and, even if we consider the film without a black main character, the conflict between men and zombie is a symbol for the ultimate fear that humans have for what is (potentially) different from them, for example, fear of another race. After Ben is killed, his body is piled up unceremoniously among many others and burned, in a process remarkably similar to lynching. Black or not, the attention payed to this moment is no coincidence. The way that this conflict ends brings us back to the idea of hopelessness, and the theme of the film: that only cooperation, not conflict, can solve (America’s) problems.

A film that has appeared in both arthouses and grindhouses for years, Night has a multileveled appeal and numerous interpretations. It became an escape from escapist Hollywood cinema; a return to reality begged for by a generation. It brings the ‘dead’ fears (and hopes) of this generation back to life, encouraging the masses to rise up against the status quo, or at least acknowledge that it’s only a façade falling to pieces before their eyes, just like the supposed humanity of the characters in the film. The way Night has revolutionized its genre, it practically demands a similar revolution from its viewers.

Works Cited

Hervey, Ben. Night of the Living Dead. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.