The Baroque Period of Music 1600-1750 European Classical Era Time Period - History

When considering the many periods of music which have existed throughout history, it is obvious that many periods have made long lasting contributions to music overall. However, the Baroque period is the most important in this respect. The Baroque period of music was the most influential because it marked the introduction of musical devices which have been used as the basis for most music since then, even in present times. The key devices introduced in the Baroque period include using more contrast in musical compositions, the development of standard scales and chords, and modulation within a piece. A few examples of this type of composition are the Brandenburg Concertos by J.S. Bach, Bassoon Concerto No. 11 by Antonio Vivaldi and for a more modern representation of the Baroque periods lasting influence, “The Song that goes like This” from the Broadway musical Monty Python’s Spamalot.

Spamalot - Song That Goes Like This

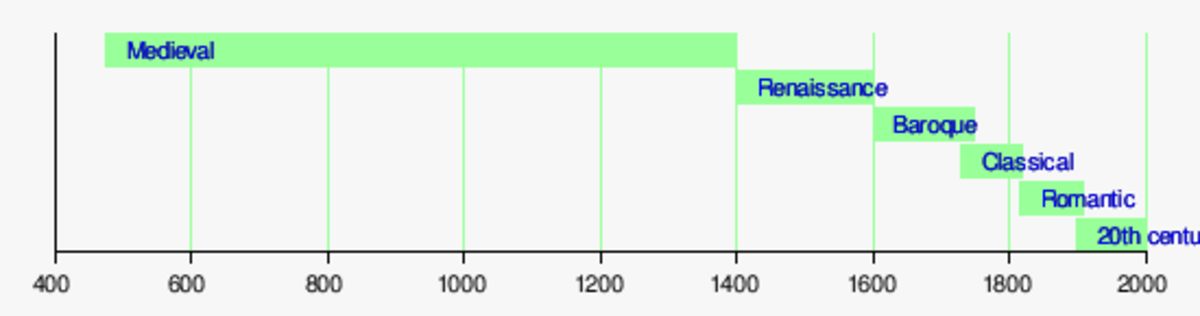

The Baroque period began in 1600 when music styles began to change from the more simplistic style of the Renaissance to the more intricate style known as Baroque. The Renaissance period of music was dominated by choral music and chants, as well as madrigals which were poems sung with instrumental accompaniment, usually for the purpose of praise (Adams 385). The music had simple rhythms and melodic lines. Music from this time was very often sung, and consisted of multiple voices sounding in a triadic harmony (Adams 384). Though this type of melodic harmony increased the complexity of the music, the music stayed within relatively simple confines in order to preserve the words instead of overshadowing them with lavish melodies.

As the fourteenth century drew to a close, a shift in power and thinking allowed music to shift from that of the Renaissance to what is known as the Baroque. To begin with, the two main composers of late fifteenth century music, Palestrina and Orlando Lasso, “had disappeared” (Winternitz 258). Major philosophers of the time such as John Locke, Hugo Grotius and Thomas Hobbes, began to question religion and the government, and developed theories of political philosophy that emphasized the individual persons influence, instead of just the king’s, and a break from religion and church rulings. All of these developments allowed for the creation of a new type of music. This new music was “…expansive and dramatic…” (Adams 439) and reflected “the seventeenth century taste for lavish, grandiose expression,” (Adams 439) contrasting with the confined music of the Renaissance.

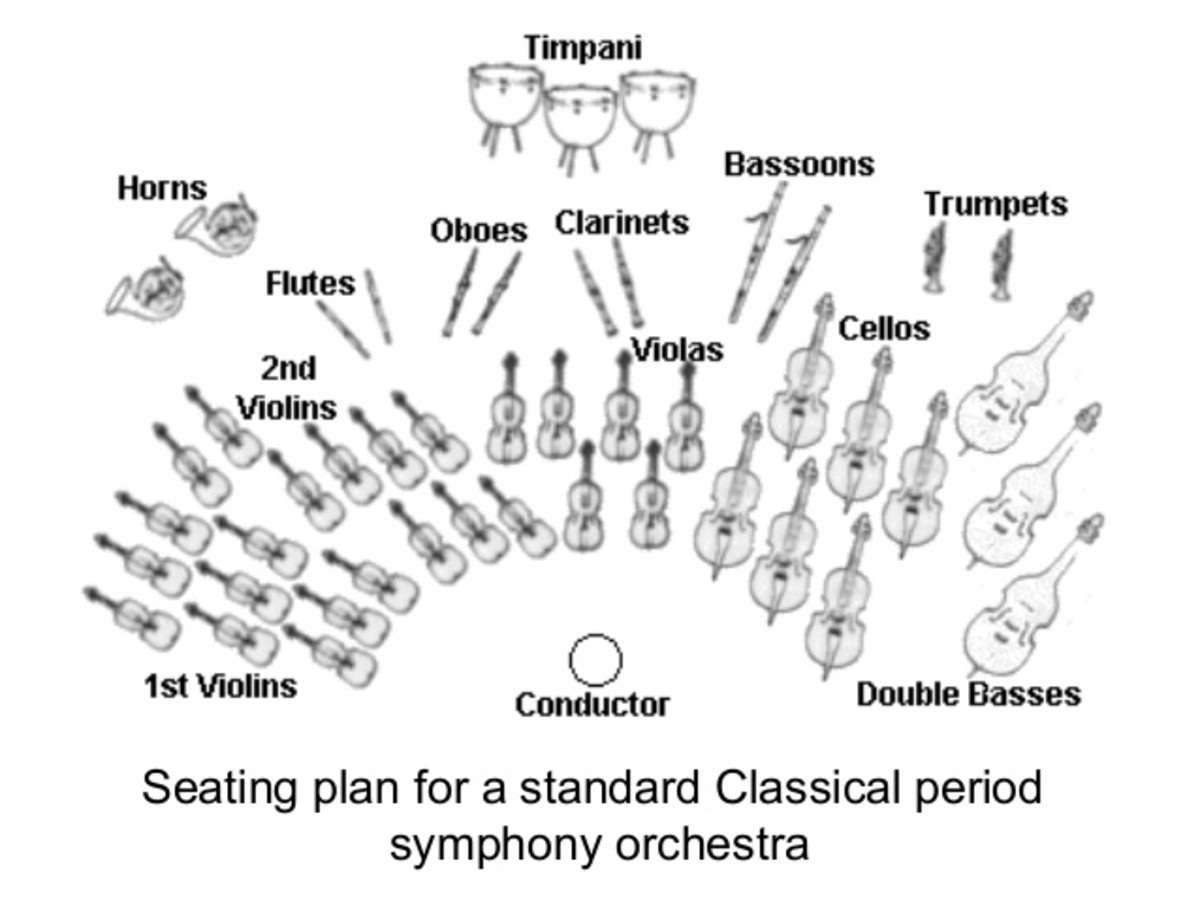

One way in which Baroque style revolutionized music was by using more contrast throughout a composition. This was due to the “…new principle of distinction between a protagonist melody and a background harmony,” (Winternitz 258). Baroque music marked the beginning of the use of separate melodies and harmonies as opposed to the polyphony used in the Renaissance period. Melodies were usually played by a group of instruments in an orchestra or chamber group or by a soloist in a new type of composition called a concerto. A concerto consists of a melody played by a soloist while the orchestra plays the harmony. Concertos became an extremely popular form of composition during this time and continued to be throughout musical history. Concertos incorporate several other forms of contrast introduced in the Baroque period. Contrast between “…loud and soft, fast and slow, declamatory and lyrical,” (Adams 439) became very popular during this time. Concertos are often composed with a fast movement, then a slow movement and finish with another fast movement. The fast movements are usually very declamatory and louder, especially the final movement, while the slower movement is more lyrical and usually softer. This form set the foundation for concertos and many other types of composition throughout history.

One example of a Baroque concerto is the Brandenburg Concertos by J.S. Bach. For example, the Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 follows this format of a fast movement, slow movement, fast movement. Within each movement the melody is carried by different sections of the orchestra, primarily the horns, winds and violins. There is also a distinct harmony carried by the other sections of the group. Throughout this concerto it is clear “…how individual instruments… trade the melody back and forth,” (History 40). There is dynamic contrast within the piece between loud and soft. The second movement is much slower and is more lyrical and sweeping, though the accompaniment harpsichord and bass string instruments maintain the metered feel to the piece, while the violins, winds and horn carry the melody. The third movement finishes the concerto with a declamatory and fast style, in typical concerto style.

During the Baroque period the foundation of chords and scales for almost all music was created. These scales and chords create tonality that is replicated in all music genres. Even “In hard rock, country, disco or most any other popular music, the same basic set of notes – scales- are used and even many of the same chord progressions.”(History 40). The most popular of these chords is a three note chord called a triad. The chords and scales of a piece determine how the whole piece sounds, and give the piece “… a sense of momentum, with one chord seeming to push towards the next…” (Adams 439). The chords also determine the mood of the piece, whether light and happy or dark and heavy. This mood can easily be changed by changing just one note in a chord by a small increment. Since the chords are often created by the musicians in the harmony, this gives a certain power to the harmony players, who may be overlooked because they do not play the more popular melody, yet they in fact control the mood of an entire piece of music.

A good of example of the use of chords and scales in music is the first movement, Allegro, of the Bassoon Concerto No. 11 by Antonio Vivaldi. The scales and chords throughout the piece illustrate how chords can affect the motion of the piece, giving a sense of building up on one chord to the next. The scales in this piece are played through chords both by the soloist bassoon and in the harmony by the orchestra. The first movement begins with a declamatory style as is typical, and continues in a fast paced style. The piece experiences a change of mood when a chord is changed from a major to minor chord and so it can be heard that the chords affect the overall piece. This concerto also displays the contrast discussed earlier. There is the contrast between the orchestra and bassoon, particularly the violins, and between the dynamics of the piece. This piece also has a ritornello form, which involves a section of the music which begins the piece and is repeated throughout the movement usually by the orchestra, in the times when the soloist is not performing (Adams 440). A ritornello “…takes full advantage of the Baroque love of drama and contrast,” (Adams 440) and also became very popular and widely used during this time and has continued to be used throughout musical history.

Another style which emerged in the Baroque period was the use of modulation in a composition. This was however very difficult in periods prior to the Baroque period and even in the early Baroque period. This was due in part to the fact that the Renaissance period had been relatively restrained and poor instruments made it difficult to change keys. It was during the Baroque period when the pitch of each note on the scale was decided, thus allowing composers to use set scales and keys in their works (History 40). Prior to this the pitch had been decided on by musicians at each performance and hence “…did not allow composers much flexibility, especially in moving from one key to another,” (History 40). In the development of scales and definitive pitches during this time, a system was also developed for tuning instruments, known as “even – tempered tuning” which “…evened out the intervals and allowed any scale to be used,” (History 40). This was one of the Baroque period’s biggest contributions to and influence on musical history since the scale and tuning systems developed during this time are still used today.

Baroque Music for Concentration

More Baroque on Amazon !

With set scales and pitches established, composers were now free to change, or modulate, the key of their pieces. Modulation is changing the key during a piece and then returning to the original key in order to “… establish a feeling of ‘home,’ depart from it to a contrasting realm, and then experience a sense of homecoming at the end,” (Adams 440). Modulation was a new concept, but became widely used and very popular. Modulation offers the audience a sense of exploration, if not some anxiety and suspense, while the notes are in a different key and then triumph and happiness at having returned to the original key. Modulation can also emphasize certain parts of a work and offers a bold climax to a piece with a friendly resolution to the original key at the end. Much like changing the notes in a chord, changing the key also changes the mood of the piece. For these reasons, modulation has been a popular technique for a very long time and can be seen in almost every composition.

Modulation can be heard both in J.S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos and Antonio Vivaldi’s Bassoon Concerto No. 11. In the Vivaldi piece, the key first changes near the end to a minor sounding key, creating a darker feel to the piece, and stays in this key for a few lines before changing back to the original key, a classic example of modulation. Also, in the Bach piece, modulation can be heard in the Allegro movement when the harmony changes to a minor sounding key, affecting the entire piece and modulating the key, only to return again to the original key a few lines later. This occurs several times throughout the movement, almost always occurring in the harmony line, showing how much power the harmony musicians do in fact have. A more popular and current example of modulation would be the “Song that goes like This”from the Broadway musical Monty Python’s Spamalot. In the song, the actors very pointedly modulate the key while singing the line “ …and then we change the ke-ey” and then continue to sing in that key before returning to the former one. This is both a classic example of modulation and an example of how the Baroque period has had a lasting effect on music, right up to current times.

The Baroque period was one of much musical change. New styles of playing were developed and much technical advancement was made. The Baroque period introduced the technique of modulation, through the development of set scales and pitches which are still the standards for current music. Baroque music incorporated much contrast into the music, contrast between melody and harmony, dynamics, and moods, which is still a technique used to give life to music. Also during the baroque period, patterns of scales and chords were developed that are still the standards for popular music today. All of these aspects make the Baroque period the most influential period of music throughout history.

More Hubs by LeisureLife

- Effects of the Automobile on Society and Changes Made by Generation

The invention of the automobile has brought more positive and negative effects than any other invention throughout transportation history. As the most widely accepted method of transportation, cars have... - Religious Myth and Structure and the Understanding of the World

Religion has been a part of most societies since those as early as the Neolithic period and perhaps for even longer. Religion has many qualities which capture the interest of human beings, such as its power to... - Mystery of Memory in Augustine's Confessions: Book X

Memory is a mysterious power, but one that is necessary for fully understanding oneself, as well as God. According to Saint Augustine, memory must be experienced through physical senses, though it itself... - Language in the Classroom

The article Why Do They Get It When I Say Gingivitis But Not When I Say Gum Swelling? explores how a students native language affects their understanding of Anglo-Saxon and Greco-Latinate... - The Breakfast Club (Movie) Stereotypes

As soon as the song Dont You Forget About Me is played, people who have seen The Breakfast Club (1985) instantly think of scenes from the classic film. When this song was paired with the movie,...

Works Cited

Adams, Laurie Schneider. Exploring the Humanities: Creativity and Culture in the west. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006. 385, 439- 440.

Bach, Johann Sebastian. “Allegro.” Brandenburg Concerto No. 2. Norbert Mattern, Vassil Ivanov, Jean de Ridder. Luxembourg Radio Symphony Orchestra. 23 February 2009 http://internal.fsu.classical.com/listen/player4/index.php?token=_R~CCiCCMZbZh_0Wr0R33ZV O9GidbZW6H~2&rnd=111

Bach, Johann Sebastian. “Allegro assai.” Brandenburg Concerto No. 2. Norbert Mattern, Vassil Ivanov, Jean de Ridder. Luxembourg Radio Symphony Orchestra. 23 February 2009 http://internal.fsu.classical.com/listen/player4/index.php?token=_R~CCiCCMZbOh_0Wr0Rd9O3 922OG69dHVMM&rnd=209

Bach, Johann Sebastian. “Andante.” Brandenburg Concerto No. 2. Norbert Mattern, Vassil Ivanov, Jean de Ridder. Luxembourg Radio Symphony Orchestra. 23 February 2009 http://internal.fsu.classical.com/listen/player4/index.php?token=_R~CCiCCMZbVh_0Wr0RMM~ MOZZW3M~39MbM&rnd=626

“History of Baroque Music in Brief.” Music Educators Journal 71.5 (1985): 37-41. 23 February 2009 http://www.jstor.org/stable/select/3396428?seq=4&Search=yes&term=Baroque&term=c oncertos&list=hide&searchUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicResults%3Fhp%3D25%26la%3D %26wc%3Don%26gw%3Djtx%26jcpsi%3D1%26artsi%3D1%26Query%3DBaroque%2 Bconcertos%26sbq%3DBaroque%2Bconcertos%26dc%3DAll%2BDisciplines%26si%3 D76%26jtxsi%3D76&item=92&ttl=3524&returnArticleService=showArticle&resultsSer viceName=doBasicResultsFromArticle

Vivialdi, Antonio. “Allegro.” Bassoon Concerto No. 11. Daniel Smith, Zagreb Soloists. 23 February 2009 http://internal.fsu.classical.com/listen/player4/index.php?token=_R~CCi~CZVGZh_0Wr0R~bC6O 2HOOGd2G~b3&rnd=202

Winternitz, Emanuel. “The Evolution of the Baroque Orchestra.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin New Series, 12.9 (1954): 258 – 275. 23 February 2009 http://www.jstor.org/stable/3257569?&Search=yes&term=Baroque&term=period&list=hide&se archUri=%2Faction%2FdoBasicResults%3Fhp%3D25%26la%3D%26wc%3Don%26gw%3Djtx%26jc psi%3D1%26artsi%3D1%26Query%3DBaroque%2Bperiod%26sbq%3DBaroque%2Bperiod%26dc %3DAll%2BDisciplines%26si%3D26%26jtxsi%3D26&item=30&ttl=31106&returnArticleService=sh owArticle