Video Games as an Art Form

Just as a precaution, the following may contain spoilers for any of the games mentioned.

As someone who’s played them ever since he was a child, video games have always been something that carries an intrinsically nostalgic value to them, but for someone like me they go beyond nostalgia and childhood memories, which seems strange or perhaps childish to some people as apparently video games are something to “grow out of”. While I was younger there was always a childlike wonder that accompanied playing video games, yet as I grew older—even when the novelty and amazement began to fade—it became clear to me why I was so attached to them and subscribe to them so much as a medium. Video games are a form of art; they aren’t going to become an art form, they don’t simply have the potential to become an art form; it has already happened. The sheer amount of aversion towards a statement like that is baffling, because to do so is to be ultimately hypocritical unless one’s list of what qualifies as art is so narrow that it contains one or two forms of media. Admittedly, video games as a whole still have a long way to go as a form of art, yet they’ve also developed quite well over the past couple decades, and more and more of them have become mouthpieces for transmitting and expressing creativity, ideas and truths to their audiences.

But first, what is art exactly?

While it’s true that video games are, in essence, a combination of multiple established art forms such as literature, film, music, and visual art; this isn’t exactly convincing enough to explain how video games can be artful. Instead, it’s more constructive to describe how video games might fit under the same category as the art forms mentioned earlier. It only seems natural to talk about what art really is before we even talk about what is considered art, and while this can seem futile as many people have varying definitions, I feel like I have to discuss what can be defined as art in order to proceed.

To me art isn’t exactly something that simply moves people emotionally or “speaks to the human condition”; but art is broadly something that creatively expresses ideas, emotions, sentiments, etc. through the self of the author(s) and these ideas can also extend from this author’s relationship and conversation between her and her audience. I have to note that this means as long as one is trying to express something through the action or object she creates, it is, in principle, art, and should be treated as such. However, this doesn’t mean that there’s no such thing as “bad” art or art that is executed poorly, but as I was thinking about what art is, it became hard for me to not contradict myself about what qualifies as art as I tried to alienate what I thought wasn’t art even though they still fit all the requirements, so I decided that as long as one tries to express ideas in the way I described, it counts. Perhaps it’d be an insult to artists and art critics and the like if I said that as long as Michael Bay was truly trying to express something in his Transformers movies, they qualify as art; but I figured that since people have already criticized it under artistic standards, I might as well give him that—they’re still pretty terrible films even if they are art, though.

The reason why I spent a whole paragraph (and I guess the following paragraph) to talk about what makes art art is the fact that it’s unconvincing and insufficient to simply say something like “Final Fantasy VII made me cry, so it’s art.” Many of my relatives cried at a wedding recently but does that mean the wedding itself is art? Not exactly. It’s a lot more complicated than that, and discussion about art in such a way—to decide to take some things and put it under “Art” and take out some other things—isn’t something to be taken lightly.

To use the same example as earlier, one could instead say, “Final Fantasy VII is art because story writer and producer Hironobu Sakaguchi expresses the loss of his mother and his concerns about the environment through Final Fantasy VII.” As Final Fantasy VII is part of one of the most successful media franchises in history, it’s important to realize that commercial products can be qualified as art, contrary to popular opinion; as many seem to deny not only video games but many other works of art the status of being art simply because the artists or their producers and publishers use the work in question as a means to earn money. Commercialism can ruin a work’s artistic integrity in a lot of ways, but that doesn’t mean that the work simply becomes a product and nothing else; artists need to earn and use money, too, after all. It’s strange to me why people are often so ready to denounce video games as an art form while lifting up other media such as literature, film, photography, and other more traditional art forms as part of “the arts”, as basically all of these things can be subject to the same commercialism, Hollywood and many books on the New York Times Bestsellers’ List being prime examples of such.

In a similar vein of criticism, many people are quick to say something like, “How can video games be art when there are things like Angry Birds or Call of Duty and other things that lack substance?” The fact of the matter is just because a medium can contain works or pieces that aren’t art or even poorly realized art, it doesn’t mean that the medium itself isn’t an art form. There are books that aren’t meant to be artful as there are movies that are simply mindless entertainment, and selfies are still photos even if they really aren’t artful at all; does all of this mean that literature, film, and photography aren’t art forms? Certainly not. As much of the video game industry is full of time sinks such as Candy Crush Saga andLeague of Legends, there are just as many if not more examples of killing time such in the film industry and other media.

Language and Video Games

Like their fellow media, video games can communicate through a sort of language unique to the medium. The most obvious example of language in art is probably literature; its language being, well, languages like English and French and Chinese, etc. But this is true of all media: painting and other visual arts use perspective, color and contrast among other things to express emotions and ideas; music theory, with all of its complexities with melodies and harmonies and counterpoints and whatnot, is the language of music; film uses montage and cinematography. Note that many of these languages also collide quite often: songs can have lyrics, films can have songs and scored music and most of them have scripts—a form of written and spoken language. The brilliance of video games is not only their encompassing of all of these forms as mentioned earlier, but their own language—their own way of conveying ideas in the form of gameplay, or how one plays the game—involves the audience in a far more engaging fashion than all the other forms of media.

Examples of gameplay’s linguistic capabilities stretch all throughout video games’ history, but there are some rather famous examples. Many of the older video games from the 8-bit (Nintendo Entertainment System, Sega Master System) and 16-bit (Super Nintendo Entertainment System, Sega Genesis) consoles often explained how to play the game through tutorials or instructions on-screen or in manuals, but games like the Mega Man series and Super Metroid are notable exceptions. A game mostly about exploration,Super Metroid has a scenario where the player is trapped in a lower level of a room and she needs to get back to higher ground.

The room has a shaft that seems to be the only way to ascend and while it’s certainly too high to jump up and you can’t climb up, there are these little monkey-like creatures who scale the shaft by jumping back and forth between the two walls. By mimicking the creatures, the player is able to return to the higher levels and also learned how to perform a maneuver that was never divulged to her, and is useful for the rest of the game. In short, Super Metroid uses gameplay to teach the player how to play the game without spelling it out to her with written language or spoken word, just as film expresses character motivations or subtext through its cinematography and imagery and how a music piece might inspire sorrowful thoughts by introducing a minor key.

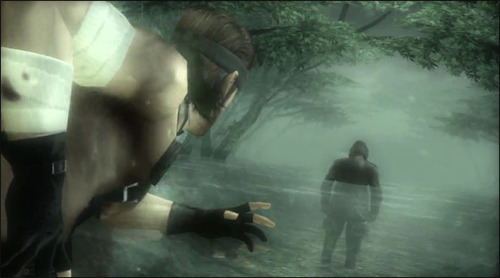

While earlier examples of gameplay conveyance were mostly for instruction, video games in the latter half of their lifespan express ideas more thematically. In Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater, the player character, Snake, has a near-death experience when he encounters the ghost of an elite soldier who has the powers of a medium, codenamed The Sorrow. The Sorrow forces Snake to “feel the sorrow of those whose lives [he had] ended,” and wade through a seemingly endless river as apparitions reach out to him and moan about their suffering.

The apparitions are actually the people that the player has killed up to that point in the game, and they actually recall how the player kills them with great detail; guards who’ve been shot in the head clutch their skull, and in one specific example, if one was killed when Snake was in the mountains, vultures could feed on his corpse, and the guard would scream “My eyes!” or something to that effect during The Sorrow sequence. The lengthy encounter actually lasts much shorter if the player didn’t kill anyone before meeting The Sorrow. In a sense, while it’s ultimately the player’s decision to kill guards on the way or sneak past them, this encourages no-kill playthroughs and seems to comment on violence and particularly violence in video games, a sentiment that would be echoed by the recent Spec Ops: The Line and last year’s Bioshock Infinite and The Last of Us.

It’s this aspect of player agency that makes video games’ artistic potential standout from the rest of their artistic counterparts. In essence, the player experiences the events that happen to the character that she plays; there’s a stronger connection between the central character or characters and the audience than there is in any other form of media. This is what makes video games what they are; after all, despite how generally terrible licensed games based on Hollywood films or television are, it’s understandable why there’s still some appeal there: people want to place themselves in the shoes of a character who was in some exciting action film or a superhero fighting crime and the like. Gameplay can drive the character motivations and thematic material home for the player because she essentially took the place of the audience surrogate and like how certain actions or decisions made by characters in films or literature may carry some symbolic significance, so do the actions and decisions made by the player in a video game with themes and issues it might want to tackle.

Not all games aspire to use the language of gameplay to convey ideas, because admittedly it’s much easier to speak with the languages of their fellow media and because, as a newer medium, many of its artists were directly inspired by artful works of film and literature to express more complex ideas, and thus use their respective languages. Regardless, many creators have used video games to talk about more pressing issues or even philosophical or ethical ideas over the past few decades. Final Fantasy VI touches on a host of ideas through vignette, if not rather lightly; nihilism, suicide, the significance of care, and even teenage pregnancy are all expressed through its largely text-driven plot and sprite imagery; its final sequence seems to reference The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri and Michelangelo’s Pièta among other things.

The first Bioshock explores Ayn Rand’s Objectivism and asks its audience, “Would it really work, even in an allegedly utopian society?” mostly through its cutscenes and scripted sequences. Final Fantasy Tactics has themes relating to class struggle, Machiavellianism, and corruption stemming from theocracy and other political forms. Shin Megami Tensei: Persona 4 has a small amount of gameplay-expressed ideas mainly about the nature of truth and searching for truth in life, and its narrative also touches on personal relationships, gender, sexual orientation, the media, ideas from Jungian psychology such as “personas” and “shadows”, and the self and its relationship with the Other.

In 2005, the late film critic Roger Ebert denounced the video game medium as a form of artistic expression during a Q&A session on his website:

“To my knowledge, no one in or out of the field has ever been able to cite a game worthy of comparison with the great dramatists, poets, filmmakers, novelists and composers. That a game can aspire to artistic importance as a visual experience, I accept. But for most gamers, video games represent a loss of those precious hours we have available to make ourselves more cultured, civilized and empathetic.”

In regards to whether or not there are games that have been considered masterpieces enough to the point that they should be compared alongside the ranks of the great artists of history, perhaps Ebert is right in saying that there currently aren’t really any games that fit the mold. Yet this is because there aren’t enough people even acknowledging their artistic potential to hail something as part of a supposed “artistic canon.” Video games are only still in their infancy as an art form and it’s only counterproductive to try to deny something as expressive and interactive as video games the status of an art form; what good comes from such an effort to alienate an entire medium from being artistic? Video games have already reached an artistic importance that transcends simple visual aesthetic value.

It’s true that video games have a tendency to expend countless hours from our lives, and this is something that is discussed at length among creators and players alike; there are no easy answers on how to solve these problems of narrative pacing and time-killing. But those hours that have already been spent on games such as the ones mentioned previously, contrary to Ebert, don’t represent a waste of time, but in fact they do have the potential to make ourselves more cultured and understand the world around us and the life ahead of us as long as people look into them analytically, and I know I’m not the only one. I’m not sure if any of the games I’ve played in nearly two decades can be placed among the pantheon of artists in our world’s history, but I can say that a few of these games listed here and many more have indeed affected mine and many other people’s lives in one way or another, and really that’s enough to warrant everyone’s attention and respect.

I intended to write this as the beginning of a series of video games as art and game design-related pieces so hopefully if I follow-through with that, the next one would probably involve how actually difficult it is to pace a video game compared to other forms of media, how this affects how difficult or enjoyable a game is, and talk further about how video games have a tendency to kill time in a more destructive manner than constructive. Thanks for reading.