- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Literature»

- Literary Criticism & Theory

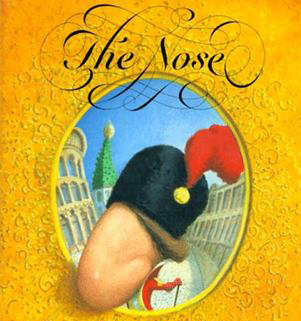

An Extraordinary Strange Event - A Look At The Fantastic in Nikolai Gogol's "The Nose"

Note: This article is on the marvelous (and hilarious) satirical short story, "The Nose," written by famed Russian/Ukrainian Author Nikolai Gogol. You can read the short story here: http://h42day.100megsfree5.com/texts/russia/gogol/nose.html

In his literary history of the fantastic, the philosopher Tzvetan Todorov defines a fantasy story as obliging “the reader to consider the world of the character as a world of living persons [reality] and to hesitate between a natural and a supernatural explanation [the marvelous] of the events described” (Todorov-33). To Todorov, true fantasy induces copious explanations and interpretations. Todorov’s definition of the fantastic revolves around three key elements: the presence of reality; the presence of the marvelous within this reality; and ultimately the hesitation between the melding of these two elements. Perhaps no other story embodies this definition to the fullest extent than “The Nose” by magical-realist Nikolai Gogol. Thus, “The Nose” is indicative of the “fantastic” under Todorov’s definition, in that Gogol, through varying literary devices, frames the focalization in vague ways, creating much hesitation between the real and the marvelous. Consequently, the presence of this hesitation and its unresolved nature, forces readers to perceive the story as ambiguous and open to many interpretations.

Gogol’s story of “The Nose” is one of satire, comedy, and utter strangeness. After waking to breakfast one morning, the barber Ivan Yakovlevich finds a severed nose in his bread. After believing he drunkenly removed it from one of his customers, he seeks to rid himself of the evidence of his crime by tossing the nose into the river. The next morning, Collegiate assessor Kovalev awakens to find his face missing its nose. Not sure of what to do, Kovalev nearly goes mad trying to find his nose. To his surprise, Kovalev finds that his nose is now walking the streets of Petersburg. Kovalev, like the reader, slips into a world where the lines between the reality and the marvelous become truly fantastical.

In order to properly fit Todorov’s mold of the fantastic, it must be exhibited that “The Nose” holds true to the three key elements of the fantastic: reality, the presence of the marvelous within this reality, and the hesitation created by the union of these two. And while all three elements are of importance, perhaps the hesitation is paramount, for it ultimately shapes readers perceptions of the story, and forces readers to rationalize. Thus, analysis of these elements will be done so according to said importance.

In terms of the first element, however, Gogol opens the story leaving no doubt that it is indeed set in reality. Much like the opening of a recited story, the narrator remarks, “On the 25th of March an extraordinarily strange event took place in St. Petersburg” (Gogol-199). Both cues to the story’s setting offer a sense of reality; while an “extraordinarily strange event” is sure to take place, it no doubt takes place in the confines of the very real city of St. Petersburg, within the real confines of time. The existence of reality in the story is exacerbated by the mentioning of several existing locations within the city, such as Nevsky Prospect (Gogol-203) and St. Isaac’s Bridge (Gogol-201).

Tangible characters and their realistic and remedial occupations also lend themselves to reality: Ivan Yakovlevich, a “terrible drunkard” and barber, (Gogol-201) and the narcissist Collegiate assessor Kovalev. Moreover, descriptions of then-current fashion and dress, as well as the use of carriages create a sense of reality. Thus, it can be concluded that the story no doubt fits the Todorov’s first requirement of the fantastic – the story is set within the bounds of reality.

Todorov’s second key element of the fantastic, the marvelous, is no doubt exhibited in Gogol’s story. After awaking one morning, Kovalev looks in a mirror to observe a pimple, only to find that his nose is missing: “…but with the very greatest astonishment he saw that in place of his nose there was a completely smooth expanse” (Gogol-202). Despite the fact that Kovalev’s nose had previously been described as being cut from his face by Ivan the barber, no gruesome and bloody cavern exists, only a smooth plane of skin. While such detail is small and vague, it nevertheless lends itself to the presence of the marvelous within the story.

Soon after as Kovalev goes out into the world, to his utter amazement, he sees a man “that was his own nose!” (Gogol-204) The marvelous has thus fully made its appearance as something between a man and Kovalev’s nose, pacing throughout the very real city of St. Petersburg. Surely, there exists no doubt that “The Nose” fulfills Todorov’s second requirement of the fantastic. Ultimately, the existence of such marvels will have much bearing on the final element of Todorov’s definition.

As stated previously, the final element, hesitation, is perhaps the most paramount. The hesitation created between reality and the marvelous can ultimately be summed up as a blurring, or inexplicable mixture of reality and the marvelous. The ways in which mental hesitation is created and framed between the real and the marvelous ultimately marks the direction the story will take, as well as its overall measure as a fantastic work. This is where Gogol truly shines as a master of the fantastic.

The first flash of hesitation between the real and the marvelous in Gogol’s story occurs when Kovalev wakes to find that his nose is missing: “He began to feel about with his fingers in order to find out: wasn’t he asleep? It seemed [emphasis added] he was not” (Gogol-202). Gogol’s language here is central. Awaking from sleep and finding that his nose is missing, it appears likely to the reader that Kovalev is simply dreaming. Yet, the author outright denies this. Or does he?

From the use of the word “seems” the author is neither stating that Kovalev is awake or sleeping. To Kovalev, all seems true, yet the reader is left wondering if this is truly a dream or not. Before resolving the situation, Gogol continues with his tale. Thus, this information remains hidden, and the situation ambiguous. Hesitation between reality and the marvelous is born.

Further on, after going out into the world, Kovalev stops to question whether his nose is truly missing: “But perhaps it was just my imagination: a nose just can’t vanish in some stupid accident” (Gogol-203). To the reader, the story appears to be giving way to some sort of dream or hallucination; hesitation will surely be resolved. But these hopes are again unanswered as Kovalev looks at his reflection in a bakery window, and finds that his nose still remains lost. Now, like the reader, Kovalev himself becomes the victim of the marvelous, and is also hesitating between reality and marvel. Gogol has thus created a connection of confusion between reader and character, adding more to the reader’s hesitation.

Perhaps the most confounding situation in the novel where the reader hesitates between reality and the marvelous occurs when Kovalev sees his nose walking the streets of Petersburg. Gogol’s description of the nose itself is key and truly exhibits his genius ability at ambiguous hesitation. In his description, Gogol writes, “a gentleman in uniform, bent over, jumped out and ran up the stairs” (Gogol-203). Kovalev then wonders to himself, “How was it even possible that his nose which only yesterday had been on his face and could not ride in a carriage or walk, -be wearing a uniform?” (Gogol-204) What is one to make of such descriptions? Is this figure a man with just a face and no nose, or is this figure simply a giant nose?

While the previous hesitations between real and marvel could have easily been rationalized as dreams or hallucinations, the hesitation here is unyielding. The nose itself, as well as its ambiguous description, is of great importance to the story’s fantastical nature. Here, the nose purely represents hesitation. The character intertwines reality - in its man-like figure, its uniform, and its occupation - and the marvelous, in it being a walking nose. But, through Gogol’s vague description, the reader is left wondering what Kovalev is truly seeing. Thus, the reader is hesitating, pondering on such irrationalities.

After several failed attempts to find his nose, and even confronting the nose itself, Kovalev becomes disillusioned with his situation. Just as the Collegiate assessor begins to realize a life with no nose, a police officer pays Kovalev a visit at his home. After asking if Kovalev has lost his nose, the officer explains his situation: “By extraordinary luck: he [the nose] was caught almost on the road. He had already taken his seat in the stagecoach in the name of a government clerk” (Gogol-212). Kovalev’s nose, it seems, has been captured. But, despite the nose being arrested in the shape of a man, the officer returns the nose in its original form by pulling it from his pocket (Gogol-213). With no explanation of how the nose became its original form again, Gogol simply continues, causing the reader to hesitate once more.

After the officer returns Kovalev’s nose, a doctor informs him that he can do nothing to help: “I advise you to put the nose in a bottle, in spirits, or better still, put two tablespoonfuls of strong vodka on it, and distilled vinegar…” the doctor explains (Gogol-215). After following the doctor’s orders, Kovalev simply accepts a life without a nose. Months later, however, Kovalev awakens one morning to find that miraculously, his nose has returned to its original residence.

While the reader searches for a rationalization, Gogol offers his final blurring between reality and the marvelous: “Perfect absurdities do happen in the world. Sometimes there’s not the slightest verisimilitude to it: at once the very nose which had been driving about the place in the shape of a civil councilor…turned up again as though nothing has happened, in its proper place, that is, right between the two cheeks of Major Kovalev” (Gogol-217). Thus, Gogol never explicitly states the cause, nor the resolution of the marvelous nose, only the outcome. In this way, neither a real or marvelous explanation is given; it is simply stated that the nose reappears on Kovalev’s face.

In his conclusion, Gogol’s narrator leaves the readers with: “But when you stop and think, there’s something to all this. No matter what anyone says, such things do happen in the world: rarely, but they do happen” (Gogol-219). Instead of erasing any hesitation the reader experiences throughout the story by means of simple explanation (as his original ending, with Kovalev waking from a dream, would imply), Gogol enhances such hesitation through ambiguity. Not only does he offer no rationalization, neither real or marvelous, Gogol also states that such extraordinary events simply occur, by means of a narrator who he himself seems hesitant about the story’s events. Hence, the story concludes in hesitation.

As one can see, Gogol has presented readers with a story filled with reality, marvel, and hesitation between the two. One must ask, however, what this does to the perception of the story itself. Because the author himself offers no true explanation of the events of “The Nose,” the story can be found quite ambiguous. The purpose of this ambiguity, however, is not to simply confuse reality and the marvelous, and therefore the reader.

This ambiguity ultimately forces readers to create many interpretations and explanations. Whether it is that Gogol is simply off-key and mad, has a castration fear from being a megalomaniac, has apprehensions of being a narcissist, or is writing a genius social critique, the interpretations themselves are not of true importance. The idea that the story induces numerous interpretations through ambiguity is the story’s greatest achievement. Thus, emphasis is placed solely on the infinite number of interpretations that can arise from the hesitation encouraged by Gogol.

In the end, through various techniques, Gogol has offered a story not easily explained or resolved. Accordingly, “The Nose” truly fits into Todorov’s definition of the fantastic. By mixing elements of reality and the marvelous, and doing so in vague ways that induce hesitation, Gogol’s “The Nose” lends itself to numerous interpretations by placing its overall significance on the interpretation - all indicative of genius and classic fantasy.

Matthew Gordon is the author of The Thin Blue Line: An In-Depth Look at the Policing Practices of the Los Angeles Police Department &

To Live, To Think, To Hope - Inspirational Quotes by Helen Keller.

© Matthew Gordon, 2011

Books By This Author:

Bibliography

· Gogol, Nicholai. "The Nose." in Worlds Apart: An Anthology of Russian Fantasy and Science Fiction. Ed. Alexander Levitsky. New York: Overlook Duckworth, 2007. 199-219.

· Todorov, Tzvetan. The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre. New York: Cornell University Press, 1975.