Essay on Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

“All Right Then, I’ll Go to Hell”: Individual Conscience and “Sivilization” in Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

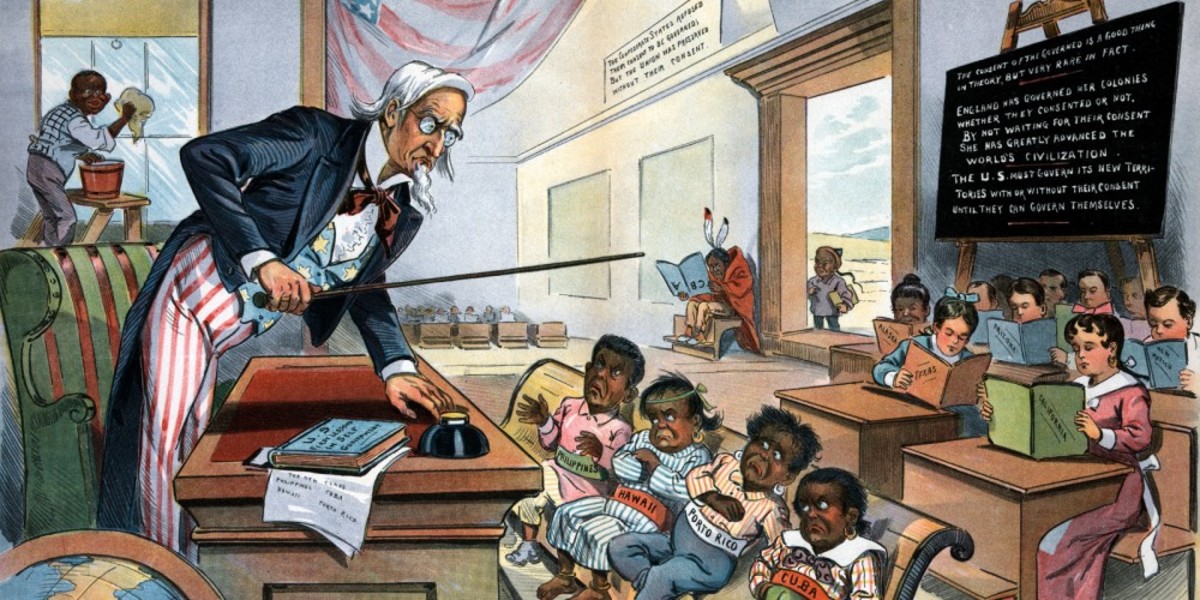

Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn begins with a “Notice” to readers that “Persons attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished; persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot,” an unusual sentiment to find in a novel written at the end of the nineteenth century, a period that has come to be known as “The Age of Reform” (43). Indeed, while the text does address a number of issues important to reformers, including racism, temperance, and education, Twain does not provide his readers with the same kind of clear-cut instruction on these issues as do many other contemporary writers. Instead, he writes with a general skepticism about the crusades for reform so popular in his time, preferring independent thinking and individual conscience to the doctrines of movements and the dictates of society.

In The Novel of Purpose, Amanda Claybough states that Huckleberry Finn is a direct reaction to the expectation that Twain, a celebrated writer, would become a “novelist of purpose,” writing books with a moral agenda (155). According to Claybough, Twain satirizes reform movements because he sees their potential to be reduced to entertainments used more as justification for self-congratulation at some pretended good than as a means of effecting real change (173). Claybough cites the camp meeting episode, in which the Dauphin convinces a crowd of churchgoers that they have rescued him from a life of piracy, swindling the self-satisfied crowd out of about eighty dollars in cash, as one instance of such self-congratulation (173), but other such instances are peppered throughout the book, from the new judge’s failed attempt to reform Pap, deemed by the judge to be “the holiest time on record” before he sees its abysmal failure and decides that “he reckoned a body could reform the old man with a shot-gun, maybe, but he didn’t know no other way” (63) to Tom Sawyer’s misguided pursuit of “adventure” at the end of the book, an act of entertainment that ultimately creates a great deal of trouble and ends in Tom being shot, but leads to no practical good for Jim, who was already free (283).

Throughout The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, we see the “sivilized” world portrayed as a misguided mass of preconceived notions, as shaped by authorities accepted as absolute, even if they are not understood by the individuals invoking them. Gregg Camfield provides, in his introduction to the novel, the example of Miss Watson misinterpreting a passage from the book of Matthew, “But thou, when thou prayest, enter into thy closet,” literally taking Huck into a closet to pray and thus entirely missing the true meaning of the Bible’s exhortation to its readers to pray in private. She holds the book’s authority to be absolute and calls Huck a fool for questioning it in spite of clearly not understanding it herself (29). It is perhaps fitting that, in a book so critical of self-congratulating reformers, Miss Watson misses the meaning of a Biblical passage forbidding self-vaunting religion. We see the same sort of strict adherence to a misunderstood text as gospel from Tom Sawyer in his reliance on adventure novels as “authorities” in the proper means of carrying out “adventures” from robberies to the freeing of slaves. Even when confronted with the reality that he doesn’t have the vocabulary to carry out the plans in the books, which insist on “ransoming” captured prisoners, a word with which Tom is unfamiliar, he insists that “We’ve got to do it. Don’t I tell you it’s in the books? Do you want to go different from the books and get things all muddled up?” (52)

While Twain’s portrayal of “sivilization” is one of misguided masses following without question authorities that they don’t understand and congratulating themselves on false reform and pretended adventures, his protagonist, Huck Finn, is removed from identification with those masses through his position as a child and furthermore, an orphaned child. Uneducated, and thus not indoctrinated into the assumptions of the people who surround him, Huck is able to scrutinize those assumptions with something like the objectivity of an outsider. Early in the book, he questions the moral and religious arguments espoused by Miss Watson and the Widow Douglas, unable to automatically accept statements that he can clearly see are objectively false, such as Miss Watson’s insistence that through prayer, Huck will be granted anything he asks for. “If a body can get anything they pray for,” he asks, “why don’t Deacon Winn get back the money he lost on pork? Why can’t the widow get back her silver snuff-box that was stole?” (54) His earlier comment to the Widow Douglas that he wishes to go to “the other place,” meaning only that he wanted a change and was unintrigued by a future in which “all a body would have to do there was to go around all day long with a harp and sing,” is interpreted as wicked by the widow, who scolds him, and it foreshadows a later point in the book when Huck makes another decision that the widow might consider “wicked” reiterating “All right, then, I’ll go to hell” (47, 230). Ironically, this decision, the choice to set Jim free from slavery, appears to postbellum readers as Huck’s most noble decision.

Seeing himself as an outsider and preferring life in the wilderness to attending school, reading the Bible, wearing “frills” (60), and otherwise behaving himself as “sivilization” would require him to, Huck is able to detect ignorance and hypocrisy in those who think themselves knowledgeable and also seems to have a better understanding of right and wrong through his own intuition than others do through reliance on authorities that they unquestioningly accept without truly understanding them. Instead of relying on the “wisdom” of the Bible and literary tradition which shape the values of a society that does not understand them, or on the words of “reforming” con artists like the Duke and the Dauphin, Huck is guided by the sympathy and friendship that he feels for Jim and, unable to ignore his conscience, resolves to “steal Jim out of slavery again; and if I could think up anything worse, I would do that too; because as long as I was in, and in for good, I might as well go the whole hog” (230). With that thought, Huck resolves to follow his own judgments, which “sivilization” would call wicked, but which readers are led to view as a rare voice of reason in a society full of blind followers and the occasional unscrupulous con artist willing to lead them.

Much like Henry James’s The Bostonians, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn calls into question the motivations of reformers and their audiences, pointing out that people are too easily willing to be led, regardless of their understanding of a doctrine, and also all too easily eager to congratulate themselves on any good that may or may not have been done. The “sivilization” of Twain’s South is less moral than it is unthinkingly fixed in its ways, and Twain’s novel seems to create an argument for individual choice over blindly adhering to the moral dictates of an ignorant crowd. Thus Twain’s opening “Notice” may be understood as an exhortation not to search for instruction within the text, but to think for oneself and interpret as one will. Twain does not want us to read literature in an eagerness to assimilate exactly the ideas and opinions of its authors and therefore warns against the search for an overt moral.

Works Cited

Claybough, Amanda. "Mark Twain: Reformers and Other Con Artists." The Novel of Purpose: Literature and Social Reform in the Anglo-American World. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2006. 152-84. Print.

Twain, Mark, and Gregg Camfield. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Boston: Bedford/St. Martins, 2008. Print.