Songs and Sonnets: Providing the Musical Context for Shakespeare's Twelfth Night

Literature and music have a very long history together. An author may reference a piece of music or make some allusion to a musical idea, or perhaps a composer will take a literary work and incorporate it into his or her music as some sort of program or libretto. However the two choose to come together, the relationship is and has been an amiable one. To narrow the idea further, the works of William Shakespeare have both impacted and been impacted by music.

Franz Liszt wrote a tone poem on Hamlet , both Peter Tchaikovsky and Sergei Prokofiev have composed ballets based on Romeo and Juliet , and, even more modern, composers like Cole Porter and Leonard Bernstein have introduced their versions of Shakespeare to Broadway.

Shakespeare himself quite skillfully incorporates the musical world of Renaissance England into his works, particularly his plays. Though many of these plays reference music in a big way, some even base entire scenes off of a single song (Ophelia’s song in Hamlet and Desdemona’s “Willow Song” in Othello ), Twelfth Nightor What You Will is unique in that it is framed by music. The play begins with Orsino’s famous monologue about music as the food of love, which would likely have been preceded and accompanied by instrumental music from backstage, and it concludes with an epilogue in the form of song, sung by the clown Feste. Musical references continue throughout the play.

It is unfortunate that literary scholars rarely get more than a cursory glance at some of these musical ideas, particularly when it comes to definable terms. Beyond being an interesting source of context and cultural information, these musical references can do much in defining characters, particularly characters like Sir Toby Belch and Feste, but also Orsino and even Viola.

![Portrait of a woman with a treble viol, c. 1720; Jan Kupeck [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Portrait of a woman with a treble viol, c. 1720; Jan Kupeck [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://usercontent1.hubstatic.com/5044470.jpg)

![Jan Dutch; Jan Verkolje (I) (16501693) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Jan Dutch; Jan Verkolje (I) (16501693) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://usercontent2.hubstatic.com/5044471.jpg)

Sir Toby

It is not long after Sir Toby is introduced that he makes his opinion of music clear. Olivia’s waiting-gentlewoman, Maria, criticizes Sir Toby’s friend, Sir Andrew Aguecheek, and calls him a fool. Sir Toby defends him with the support that “He plays o’th’ viol-de-gamboys, and speaks three or four languages word for word without book…” (TN 1.3.21-22). Later Sir Toby speaks condescendingly of Sir Andrew, but that is a different issue. The “viol-de-gamboys” is Sir Toby’s word for the viol da gamba.

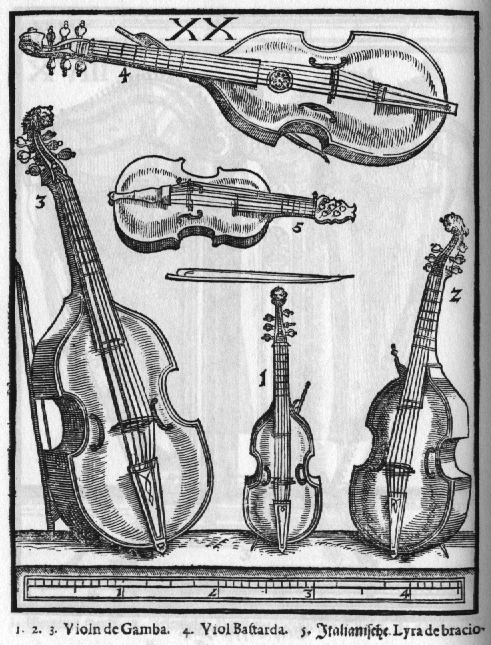

The viol da gamba is a member of the family of viols, which were the common brand of bowed instruments at that time. The viols were broken up into two categories: the viol da braccia (an instrument played on the arm, like the violin or viola) and the viol da gamba, a “leg” viol. This second type of viol was either placed between the legs or rested on the lap, depending on the size of the instrument. Though they were used as solo instruments, the viol da gamba was difficult to play single note melodies on because of its shallowly rounded bridge. This made it an ideal accompaniment instrument because the playing of double-stops was easier (Long 18).

Sir Toby’s mention of the instrument at this point in the play shows his belief that such a skill somehow enhances Sir Andrew’s level of education, and therefore his character. Such an idea would definitely be consistent with the time, for though itinerant musicians were not viewed with high regard, most gentlemen knew something of music, and a viol was a popular instrument choice (Elson 75).

Later in the same scene, Sir Toby displays his experience with dancing by mentioning the specific dances like the galliard, cinquepace, jig, and coranto (TN 1.3.105-112). The cinquepace is an early form of a galliard, and is so named because the dance itself consists of five main steps. A galliard is a lively dance in triple meter and consists of two or three evenly-measured phrases. Also in triple meter, the coranto is a more sprightly dance (coranto being the Italian form of the English country dance). The jig, yet another triple meter dance, was originally Scottish (Naylor 115-121). Dances like the coranto and the jig can be related to the stylized dances used in the suites of composers like Johann Sebastian Bach just a century later. In this passage, Sir Toby expresses his opinion that the ability to dance is a virtue that should not be hidden.

Next we see Sir Toby actually interacting with music itself when he calls for the singing of a catch, a type of round that was short and simple. These were generally folk-like in nature and, though popular, were not considered high art (Long 2). The character Malvolio illustrates this opinion when he chides the men for their singing and asks, “Do ye make an alehouse of my lady’s house, that ye squeak out your coziers’ catches without any mitigation or remorse of voice?” (TN 2.3.80-83).

So while Sir Toby approves of the gentlemanly pursuits of instrument playing and dancing, he also participates in the less gentlemanly alehouse songs. The choice of catch in this scene is one titled, “Thou Knave,” which is particularly appropriate for Sir Toby. The words say, “Thou knave, hold they peace, and I prithee hold they peace,” (Long 173) which is something Sir Toby is told to do more than once during the play. In the very same scene, only a few lines later, Maria says, “For the love o’ God, peace” (TN 2.3.77).

In the same act and scene, Sir Toby displays his knowledge of several other popular ditties by referencing “Three merry men be we” and “There dwelt a man in Babylon, lady, lady.” One particularly interesting lyric that he quotes is this: “‘O’ the twelfth day of December” (TN 2.3.76). At first glance, one might be tempted to relate this line to the title of the play, but the phrase “twelfth night” refers specifically to the celebration of Epiphany, which occurs in January. Unfortunately, there is no known song with this phrase in it. One scholar references it as a line from a “narrative ballad,” but leaves it at that. Others simply say the song “has not been identified.” I. B. Cauthen, Jr., suggests that perhaps Sir Toby is attempting to sing the ballad “The Twelve Days of Christmas,” but it comes out wrong in his typical Sir-Toby-garbled language, that is to say, he is drunk (Cauthen 182-185). This seems plausible, and would lead back to the original thought, since the twelfth day of Christmas is, in fact, Epiphany.

Feste

Another character who participates in the musical scene is Feste, the clown in the play. Most of the music that surrounds him serves to confirm his rank. He is often called upon to sing (it is only upon his arrival that Sir Toby calls for the singing of a catch), and it helps that he seems to enjoy bursting into song, whether asked to or not. In Elizabethan drama, the songs were given to “secondary characters,” generally one of lower rank, like a clown or a tradesman (Long 3). Feste’s choice of instrument (the pipe and tabor) also point to a lower rank (TN 3.1).

The pipe was considered a “vulgar instrument” by the upper class of the time, but it was a convenient one to play because it only required one hand. Having a hand free allowed the pipe to be combined with another instrument, often something percussive like the tabor (Long 22). The smaller tabors were generally the ones combined with the three-hole pipe (like the one Feste would have used), though the drum size could vary. Often larger tabors were used with a group of hautboys (an early from of oboe) because the reed instrument required a bigger sound. The tabor itself was two-sided drum made out of wood and skin (Long 26).

It is with his songs in addition to his wit that Feste teaches both the characters in the play and the reader. Perhaps in his music we see a more sober side to the clown. The first song he sings is at first glance a trite little love song, but in it Feste speaks of the fleetingness of youth. He says:

“What is love? ‘Tis not hereafter,

Present mirth hath present laughter.

What’s to come is still unsure.

In delay there lies no plenty,

Then come kiss me, sweet and twenty.

Youth’s a stuff will not endure (TN 2.3.43-48).”

The second song that Feste is asked to sing is also about love, but it takes a more heartsick view:

“Come away, come away death,

And in sad cypress let me be laid.

Fie away, fie away breath,

I am slain by a fair cruel maid (TN 2.4.50-54).”

The next comes two acts later, and is more of a ditty than the two ballads we have just seen. In this scene, Feste teases Malvolio by playfully singing “Hey Robin.” If Malvolio only listened, there would be some truth for him in the lyrics: “‘Alas, why is she so?’ . . . ‘She loves another’” (TN 4.2.70 and 72). At the end of the same scene, Feste quotes a parting verse to Malvolio. Though there are no stage directions to suggest that this verse was sung, the author of Shakespeare’s Use of Music, John Long, believes that Feste’s propensity for song would indicate that it very well may have been sung (Long 179).

Finally, Feste closes the play with a song for epilogue. In this he discusses the aging of men from child to adult to lover to elder, and implies that no matter who are or what stage of life you are in, everyone suffers. The song is permeated by a sort of double refrain that says, “With hey, ho, the wind and the rain” and “For the rain it raineth everyday” (TN 5.1.376-395).

Orsino

Though Orsino is not as involved in the actual music making in this play (which is common for a character of elevated rank in an Elizabethan drama), he does have a lot to say about music (Long 3). Orsino opens Twelfth Night with a very famous monologue about music as the food of love.

He continues with this philosophy of music later when he calls for a specific song to be sung (he ask Viola, as Cesario, to sing, but the ballad is eventually sung by Feste). In this scene Orsino gives music a very high power. He speaks of it being able to relieve his passions. Viola responds to him in kind when she says, “It gives a very echo to the seat where love is throne” (TN 2.4.20-21). Finally, Feste sings the asked for song, which mirrors the very Petrarchan idea of love that Orsino embodies when he is pursuing Olivia (he is not nearly so melodramatic when he expresses his intentions towards Viola, thought at that point he has only just found out that she is, in fact, a woman).

Viola

Finally, comes Viola who does not participate in the musical activities at all. When she is Cesario she is once called upon to sing, but is relieved of the duty by Feste’s presence. She is important to the this conversation, however, not so much because of what she does or says, but because of her name which is a homonym with a musical instrument.

The viola is a member of the violin family. Violins of this time had a very harsh sound, and were not really in general use in England until the latter half of the seventeenth century. The viola is a slightly larger instrument than the violin, but is played with the same general technique. The choice of such a name for Viola’s character is particularly poignant, because the instrument, though still a treble instrument, has a slightly lower (and more masculine) range than the violin.

Sources

Cauthen, I. B., Jr. “The Twelfth Day of December: ‘Twelfth Night’, II.iii.91.” Studies in Bibliography. Virginia: Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia, 2 (1949). 182-185.

Elson, Louis C. Shakespeare in Music. London: David Nutt, 1901. Facsimile. Chestnut Hill, MA: Elibron Classics, 2007. Print.

Long, John H. Shakespeare’s Use of Music A Study of the Music and its Performance in the Original Production of Seven Comedies. Gainsville, FL: U of Florida P, 1961. Print.

Naylor, Edward W. Shakespeare and Music. New York: Da Capo Press and Benjamin Blom, Inc., 1965. Print.