Roman Literature: What Does It Say About Rome?

When we look at some of the great works of ancient Roman literature, specifically the works which fall into the epic poem genre and those of a satirical nature, we begin to notice a striking difference in what these two different literary approaches tell us about classical Roman culture, but which of the two provides a more accurate portrayal? Did the ancient Romans fit more within the uplifting, heroic tone and emphasis put forth by authors like Virgil in epic poems like the Aeneid, or did the culture have more in common with the Rome we see in satires and farces like the Apocolocyntosis and Satyricon? How would historians view our own culture if presented with only a great American novel of colonial heroism and a series of scathing satires like South Park, and would it be a true depiction of real life? Should a line be drawn between what a person or a people (in this case classical Rome) considers a virtuous, heroic ideal and the standard that people really live up to, or are intentions all that really matter? Considering all of this and more, I would argue that while satirical works probably do provide a more accurate depiction of Roman culture as it really was, the works of epic poetry by classical Roman authors like Virgil still hold a great deal of relevance that should not be ignored.

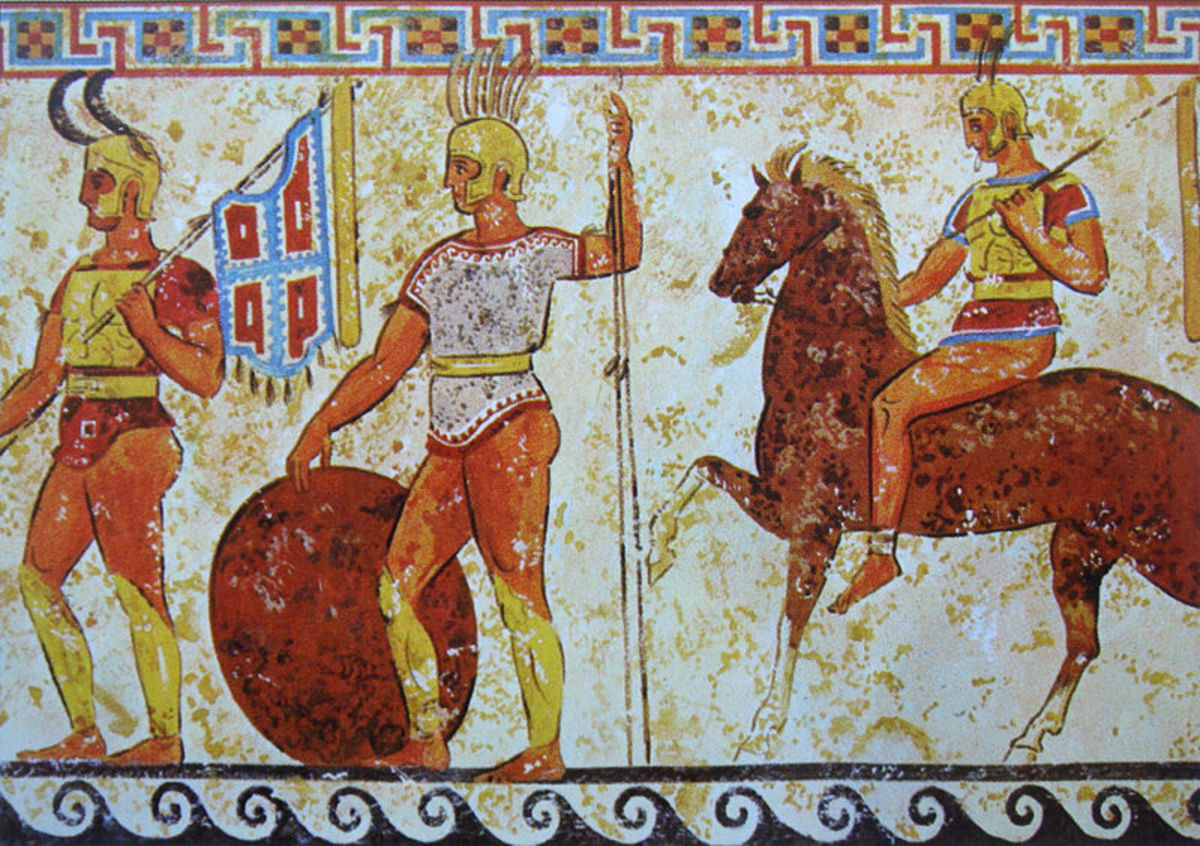

When we consider any work of literature, be it epic poetry, satire, or anything else, attention should always be paid to the general tone and emphasis of a piece, as well as the intentions of the author. So what kind of people was epic poetry written for, and was it different from the audience that satire was intended for? We know that most if not all of the authors whose work has survived from ancient Rome as a civilization were wealthy and attached to a patron, often being men from within the social circles of the Emperor himself. In order to continue on as authors, they had to, of course, do a certain amount of playing to the tastes and whims of the powerful elites within society, the men of old money and patrician lineage that had a certain romantic view of the heroes of the old days. As such, the warriors of epic poetry are Aeneas-like figures brimming with virtus, and a dim view is given of the up and coming new rich seen in characters like the Satyricon’s Trimalchio and the very real figure known as Narcissus (who we see in the Apocolocyntosis.) When we look at both Virgil’s Aeneid and works like the Satyricon or the Apocolocyntosis in this light, it is easy to separate them not only by focus, but also by the goals of the authors. The Aeneid, being a work of historical significance seen more or less as fact by the Romans of the classical period, as well as a piece wrapped heavy in the concepts of the Roman ideal, wasn’t something that was meant to be laughed at. The Aeneid was written for a very specific purpose– it is a myth-laden account of the creation of the Roman people that takes place before the story of Romulus, Remus, Rhea Silva, and the other players in the legend of the founding of Rome. Written hundreds of years after the events that the Romans, at least, seemed to believe had actually taken place, it is a piece that is meant to inspire pride, to instruct and show what it meant to be of Roman descent. The Satyricon, however, has a very different purpose. Unlike the Aeneid, it is a work of literature that is meant to be laughed at, and it seems to have been constructed by the author with the tone, points and intentions of someone not only interested in garnering laughs, but also at poking at some of the greater issues within society (like the fact that educators and artists never seem to get paid enough, and the unrefined brazenness of the New Rich.) Unlike the Satyricon, the Aeneid is very strong in its presentation of what we’ve come to see as traditional Roman values, the virtus of severitas, gravitas, and especially pietas. We see this in the fact that, even though Aeneas is in love with Dido, he does not shirk his duty to the future Roman people and chooses instead to sail on to his destiny without her. Sure, some might see Aeneas’ abandonment of Dido as ignoring his duty, his pietas, but I think the fact that, as the task of bringing his people to the future site of Rome was one that both his people and his gods, indeed all future generations of Romans depended upon, it took precedence over a questionable marriage with a woman who was a little more than a foreign queen of a nation that Rome would later war bitterly with. Aeneas is even repeatedly associated with the notion of pietas, being called “the pious chief”(Aeneid 11.3) and he demonstrates how fitting the title is every step of the way, even making sacrifices to the gods when they withdraw from the conflict to allow things to work out between mortals (as they did in book 10.)

As a whole, the Aeneid is just packed with strong, virtuous men like Aeneas who win through while expressing proper Roman values and depictions men who, like Turnus, go against those values and therefore fall. It is no wonder that Augustus loved it– the Aeneid is so very full of the Roman ideal, and it raises Roman values to a pinnacle while casting down the wicked at the point of a sword or spear, more or less. Through the killing of Turnus in the end of the Aeneid, for example, we see a clear blow dealt for both pietas and severitas. We see this in the fact that, though initially Aeneas was willing to spare Turnus, he notices “The golden belt that glitter'd on his side, / The fatal spoils which haughty Turnus tore/ From dying Pallas,”(Aeneid, 12.1365-1367) and then forgoes mercy to fulfill his duty in an unflinching act of virtus, slaying Turnus then and there and satisfying his duty to both Pallas (as his charge/student) and Evander (as Pallas’s father.) Everything within the text seems built to further values and an almost nationalistic pride in Roman citizens, the people who would not exist without the grand line of “Roman triumphs rising on the gold” (Aeneid VII.830) as portrayed on the shield given to Aeneas as the most powerful depiction of virtus in the text.

Satirical pieces like the Apocolocyntosis and the Satyricon, however, were not necessarily constructed to so directly further good Roman values or show the people what a good Roman looked like. Instead, they took an opposing approach, exaggerating and inflating the mundane and the fallibly human while observing the human condition at its worst in order to bring that which is most blindly unethical to the pubic eye. The demonstration of virtues do not figure as directly in satire as the way that they are seen in the actions of the heroes of epic poetry, and rather it is this absence which, more often than not, inspires humor. There is no severitas, pietas or gravitas in the way Corax (Eumolpus’s hired free man) complains constantly about having to carry such a heavy load and even lifts “his leg again and again, and filling the road with a filthy noise and a filthy stench.”(Satyricon, XIV) and yet the moment gets its point across because it is funny, because even though it is not the pinnacle of the Roman ideal by any stretch of the imagination, it is real. Unlike the characters of the Aeneid, the Satyricon’s cast are lecherous and lusty, greedy and forever indulging their various appetites in luxurious and what might seem to be decidedly un-Roman (but in fact thoroughly Roman) ways. It is in this way that satires like the Satyricon do, however, present a much more valuable and accurate view of what Roman culture was really like merely via the fact that, instead of being concerned with or driven by heroism and matters of an epic nature, they focus on the mundane, and it is this focus on the everyday that creates the humor which powers them. They bring forth and elaborate on the baths, the faux athletics, the parties and a thousand other licentious activities that the Romans indulged in during the imperial period, right down to the detail of the slaves who run back and forth with silver bowls to catch their masters’ urine. Sure, there are characters whose deeds are inflated to epic proportions (like Pyrgopolynices from Plautus’ Miles Gloriosus and, in places, Claudius in Seneca’s Apocolocyntosis,) but the humor comes from the ridiculousness of these inflations and the fact that the audience knows the truth is actually much more ordinary than what has been jokingly presented. It is this constant use and representation of the ordinary that universally gives the humor its impact, meaning that, as readers, we’re more immersed in something akin to ordinary life for the ancient Romans with satire than with epic poetry, even if only because of the settings. We don’t see the little things of daily life in broad, sweeping, heroic pieces like the Aeneid, and I doubt Virgil would have ever considered adding a scene to his epic where Aeneas did anything more lusty or gluttonous than his trist with Dido. Only in satire do we see the kinds of foods that people ate, details, however exaggerated, of the lives of slaves, the kinds of activities that people engaged in, the athletic sports, the leisurely bathing, or any of the little details, like the fact that the Romans had libraries or ate while half-reclining on dining couches. While the Aeneid strains to provide a heroic ideal of what it means to be Roman, satires like the Satyricon and the Apocolocyntosis show us a vision (albeit a humorous and slightly exaggerated one) of how it really was, and therein lies the key. In tracking down which genre is more faithful to reality, it would simply be a matter of looking at the level of exaggeration involved in the presentation of a given story. As an epic concerned with war and heroic deeds which provides a main character brimming with ideal, the Aeneid is far more fantastic and far further from reality than the presentations in satires like the Satyricon, where the educated and thoughtful are poor and rich freedmen use their newfound wealth and bravado to try to put themselves on the same level as those of older money.

While both Virgil’s Aeneid and Petronius’ Satyricon take a very open observational approach to the characters who exist as the focuses of each story, leaving their actions mostly open for interpretation instead of dragging them out and highlighting them as positive or negative as works like the Apocolocyntosis do (setting aside, of course, all the references to Aeneas’ piety, which don’t come across with the impact that Seneca’s condemnations of Claudius do,) we can draw a dichotomy here too between the ideal that Roman people would have seen as being the epitome of Roman values (in the form of Aeneas) and the complete opposite (which is embodied by all of the characters in the Satyricon.) This near-impartial means of viewing either story could be seen as both beneficial (the author strived for a closer and less heavy-handed approach to the subject) or as perhaps not so beneficial, as we have no real guide (except actual historical accounts and what we can glean from what is left of their civilization) of whether it was normal for Romans to be full of virtus or completely lacking in it. Assuming that most people fell somewhere in the middle (as they do today), we may look at events like the dinner with Trimalchio and the scene which features his mock funeral in book 10 and wonder how well it reflected the attitudes of normal people in classical Rome. Granted, we know that very, very few people were as well off as Trimalchio, but everyone had patrons, and if even the poorest person were to be given an invite to a dinner such as this, how would we know that things like the wild boar which is presented at dinner with birds sewn into its flank are meant to be over the top and humorous and not just a really bizarre aspect of cultural custom?

Another cultural aspect that both epic poetry like the Aeneid and satires like the Apocolocyntosis and Satyricon take very different approaches to the presentation of is religion and Roman beliefs regarding an afterlife. While the Apocolocyntosis presents gods and goddesses in a similar and fantastic fashion to that of Virgil’s Aeneid, other pieces such as Miles Gloriosus and The Satyricon present them in a fashion that seems more accessible and acceptable to modern readers steeped in a background of technology and science. Sure, Pyrgopolynices constantly refers to Jupiter and other gods in his speech, and Encolpius himself has to deal with the wrath of Priapus, but it doesn’t go any further than that. Like Homer’s Odyssey, the Aeneid is full of gods, goddesses and other fantastic beings that interact with humanity and act like men and women of abnormal power and influence. In the genre of epic poetry, the world of the mystical and the supernatural has a much stronger impact on the world of man than it does in satire, where everything is reduced to the most ordinary and very little escapes being poked fun at. Looking at the popular gravestone inscription which states: “I was not, I was, I am not, I care not” and the popularity of philosophies like Epicureanism that leaned more toward the physical than the spiritual, history itself seems to paint a picture of a classical Rome that, in practice, may not have held out much hope for an afterlife, and here I think we have one of the strongest cases for the Satyricon being closer to the reality of classical Rome than the Aeneid. While we may never know if the original Satyricon in its collected glory ever contained a chapter where Encolpius makes his own Aeneas/Odysseus type journey into the underworld, the extant text as it stands features almost no mention of spiritual elements, and those few that it does mention are almost caricatured, like the use of Priapus and his curse upon Encolpius which reflects Poseidon’s wrath against Odysseus. Another reference to Roman spirituality can be seen where the Satiricon mentions the Lares or “Household Gods,” though this happens only in passing, saying that they were brought in during the dinner with Trimachio by slaves who “set on the table images of the Lares with amulets round their necks, while the third carried round a goblet of wine, crying, ‘The gods be favorable! the gods be favorable!’”(Satyricon, IX) Presented this way, the Lares almost become part of the circus that unfolds in the Satyricon, revered, but in an almost mocking sort of way. The Aeneid, however, actually goes in a strong and positive direction with the Lares, emphasizing the importance of these household gods, not only by making more references to them than the Satyricon, but by actually containing a line within the text where Aeneas demonstrates their importance to Roman tradition by saying: “My household gods, companions of my woes, / With pious care I rescued from our foes.” (Aeneid, 80.) As expected of a true Roman who values his Lares like family, Aeneas saves them as he leaves, but doesn’t parade them around and dress them up and make a big show about them. He has that sober-mided seriousness, the severitas to treat his Lares with the respect that they deserve (unlike those of a freedman like Trimalchio.)

All in all, looking at epic poetry like the Aeneid and satires like the Satyricon and the Apocolocyntosis and asking which is closer to the truth of what it was really like in classical Rome quickly becomes akin to looking at a great American film like Forrest Gump and a pair of satires like South Park and Team America: World Police and asking which more accurately represents contemporary America. Are we, as a people, more like the celebrities and the paragons of American moral virtues we celebrate so widely, or are we more the modern day incarnations of Trimalchio, Eulompus, Encolpius and Ascyltos, chasing after our own personal Gitons? The truth is, I think, that we, as was the case with the people of classical Rome, are all individual shades caught somewhere between the ideals of society depicted in the epics and the exaggerated human-ness of satire. We, like the Romans, know what is right, have ideals and heroes that we look up to, and yet we are all still so fallibly human.