Two novels about racism

Not easy - but definitely worthwhile - reading

I have recently read two novels about racism, both published in the 1950s, one describing the persecution of Jews by the Nazis, the other the oppression of blacks by the South African apartheid regime. I do not make any facile identification of the two sets of experiences, but rather draw from the two books some of the effects of racism and prejudice on those who suffer under racist regimes.

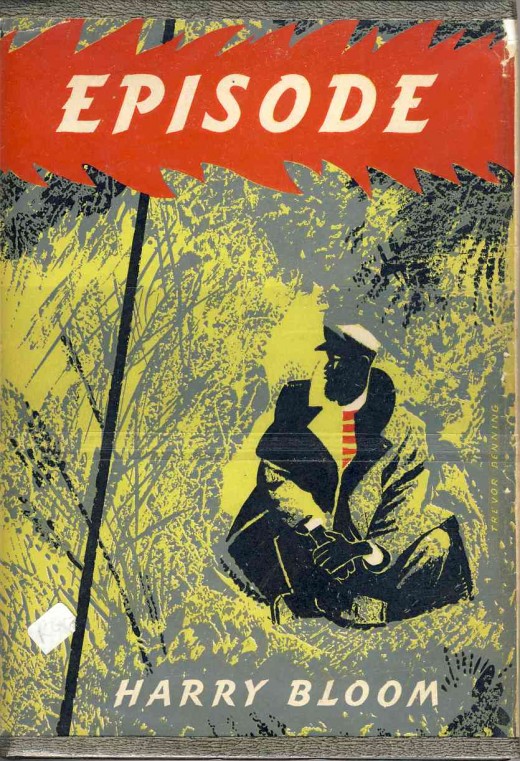

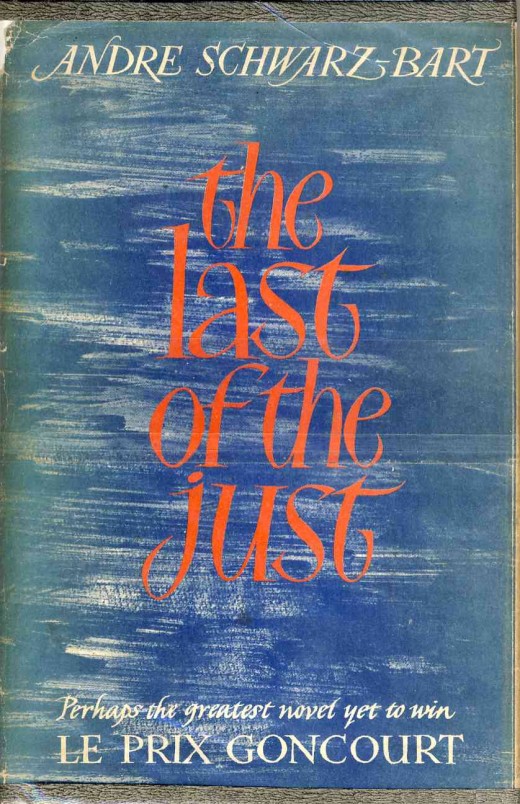

The two books are Episode by former Johannesburg lawyer Harry Bloom (Collins, 1956, re-issued as Transvaal Episode) and Andre Schwarz-Bart's Le Dernier des justes (1959, Editions Du Seuil; The Last of the Just, 1960, Martin Secker and Warburg).

Neither book is particularly easy reading, but both are very worthwhile reading. They are both also clearly fiction, though equally based on the real experiences of real people.

An interesting parallel between the two books is also that a key figure in each story offers himself up, almost sacrificially, to the oppressors, and each is killed for his action.

The authors

Harry Bloom was born in 1913 and studied at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg after which he practised as an advocate. He married his first wife Beryl in 1940. Bloom went to Britain to work as a war correspondent during World War II.

Bloom wrote Episode after the Defiance Campaign against the pass laws in the early 50s. The novel was banned by the apartheid regime for being “seditions” and won the British Authors Club Prize for the best novel of 1956.

Bloom worked with Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela as a lawyer and was a close friend of Bram Fischer, one of the defence team at the Rivonia Trial which led to Mandela's incarceration on Robben Island.

In 1960 Bloom wrote the play King Kong which became the celebrated “jazz opera” of the same name. In 1962 he wrote, while in prison for his political activities against the apartheid regime, his second novel, Whittaker's Wife .

In 1963 Bloom left South Africa for good, leaving Beryl and their two children behind. He died in 1981.

Andre Schwarz-Bart was born in France in 1928, just four years after his parents had moved there from Poland. He joined the resistance in the early years of the war and his first novel, Le Dernier des justes, was based on his experiences during the war.

Andre was the only survivor in his family, the rest all perished in Auschwitz.

Schwarz-Bart married fellow-novelist Simone and went to live with her in her native Guadeloupe, where he died in 2006. Their son Jacques is a jazz musician who plays saxophone.

With his wife he wrote Pork and Green Bananas (1967) and possibly also with her collaboration A Woman Named Solitude ( 1971). His last work, In Praise of Black Women , was published in 2001.

The novels

There are, as noted above, some interesting parallels between the two novels, as well as very important differences. The first, and most obvious difference, is that Episode is a novel of Africa, and of South Africa in particular. It resonates with the characteristics of the South African experience of racism, in which the oppressed are the majority, the indigenous people, whose land has been expropriated from them and on which they find themselves landless and rightless. The Last of the Just , by contrast, is a very European novel, rooted in the experiences of a minority people who are, like their African counterparts, landless and rightless, due to the viciousness of Nazi racial ideology and practice.

The resonance of the Jewish experience of discrimination with the experience of South African blacks is interestingly highlighted by many Jewish anti-apartheid activists. An example is Ronnie Kasrils, former freedom fighter and later Cabinet Minister in the ANC-led government of South Africa after 1994: “I always took the injunction of loving one's fellow human beings as oneself to heart. South Africa made me see that injunction specifically in terms of applying it across race, colour and creed. … I think it's an important part of being a decent human being, or striving to be one. I am positive about people, their life force. This is the Judaism in me – the belief that human life has tremendous value, that human beings can soar to the clouds irrespective of the barbarity that they can sink to. I've found that in life.” (From an interview published in Cutting Through the Mountain, edited by Immanuel Suttner, Viking, 1997).

The late Ronald Segal, another Jew intimately involved in the struggle for liberation in South Africa, put it this way: “...I believe now, that a people with a past infused by oppression and suffering is charged with a special responsibility, to remember and remind: to redeem that past with a creative meaning; to recognise and insist that we must treat one another as equally human, beyond differences of race or nationality, religion or culture, if we are not to become mere beasts that talk.” (From the Preface to his great book The Black Diaspora, Faber and Faber, 1995).

While The Last of the Just follows the history of anti-Semitism through some seven centuries, culminating in the horrors of the holocaust, Episode is concentrated on the events of a few days, though within the context of a few years.

Episode

“His story never happened, yet every word of it is true.” - Alan Paton, cover notes.

The "real character" of Episode, as noted by renowned South African writer Alan Paton, “... is the location itself (that part of every South African town set aside for the African people) ... and Mr Bloom portrays it with a fidelity and a skill that command my admiration.”

In his foreword to the Fontana edition of King Kong (1961) Bloom wrote this about the townships in which blacks lived (the term “location” was replaced by “township” by most blacks, seeing the former word as somewhat demeaning): “Africans lead bitter, frustrated and tragic lives under apartheid, but hopelessness is not the spirit of the townships. On the contrary there is a feeling of youthful strength and courage, of communal warmheartedness and laughter, of indestructibility. I cannot explain why this is so, except perhaps by saying that in spite of the ugly interim in which they live, Africans seem to feel instinctively that the future belongs to them.” (Author's italics).

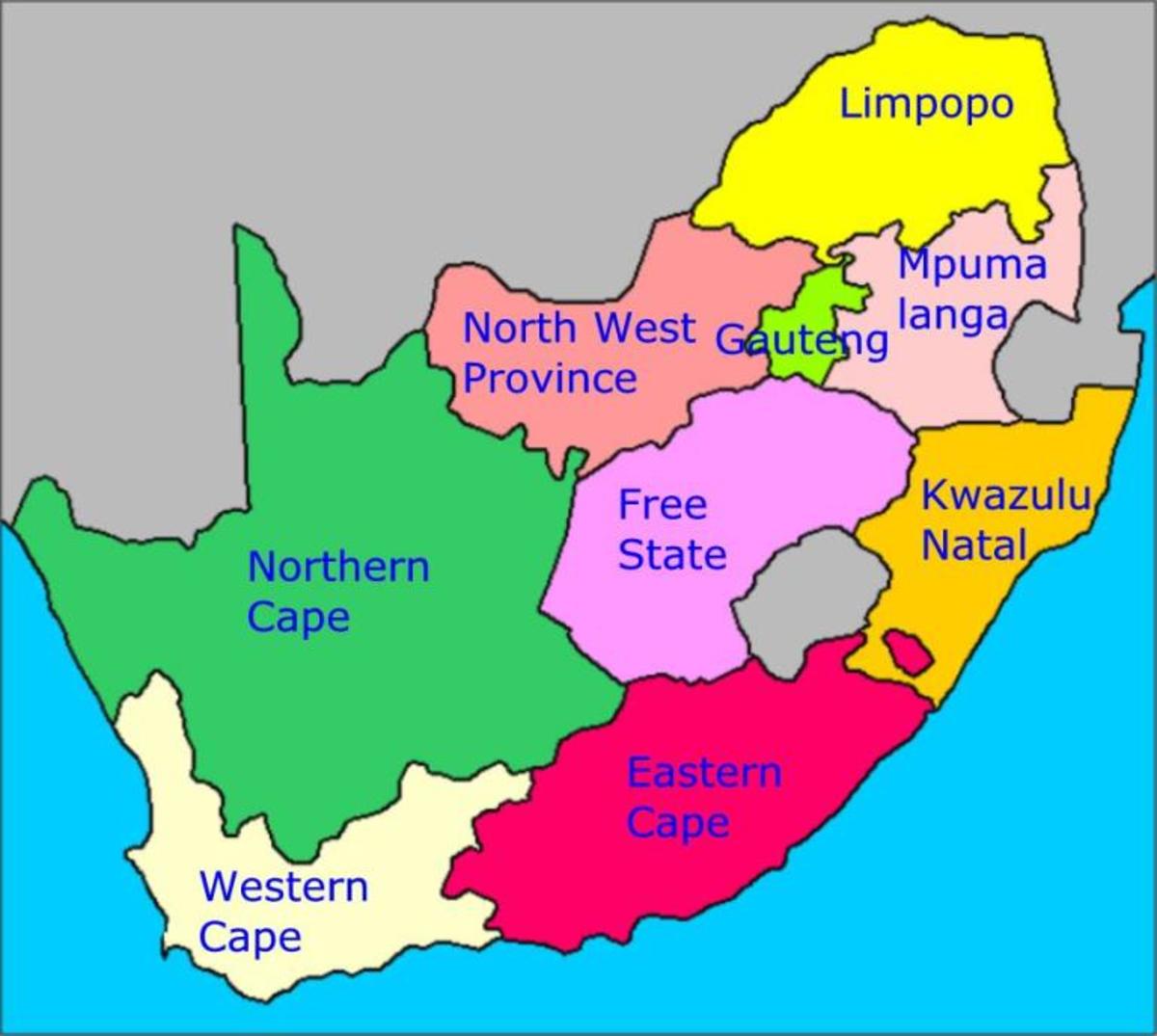

Episode chronicles events in the small town of Nelstroom (a fictional place loosely based on the real town of Nelspruit in the Mpumalanga Province, formerly the eastern Transvaal) and its “location”:

“The whole town has a clean and tidy look, and with the mountains behind and the green valley rolling out below, it is pretty and sheltered and peaceful. This is Nelstroom as the passing traveller sees it. This is the town that the visitor likes to remember. But there is another town, a submerged half, an ominous counterpart that lives within its shadow. The people of Nelstroom seldom speak about this other town. They would prefer not to think about it. But it is always present, somewhere, in their thoughts. Like captor and captive chained together, the two towns are never free from one another.”

The town and its shadow self are represented in the novel by, respectively, the “location superintendent” Hendrik du Toit, and the representative of the ANC in the location Walter Mabaso.

“Hendrik du Toit was not a typical superintendent, but then there is no such thing. Every superintendent works out his own problems in his own way, and Du Toit's way was about as good as any man's attempt to handle the dilemmas of his peculiar job.”

“One day in the hot, dry November of 1952 a new man came to live in the location...He travelled by train from Johannesburg and it was late afternoon when he reached Nelstroom...There was something about this man that drew eyes to him, but it was hard to say just what it was.” Thus Mabaso arrived to take on his key role in the location.

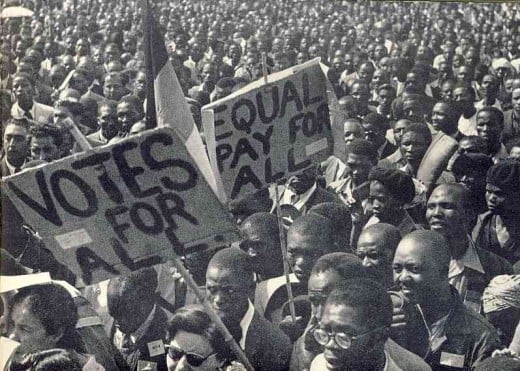

The timing is critical for an understanding of the novel. In 1950 the government had passed the Suppression of Communism Act which defined as communist any activities designed to bring about “any political, industrial, social or economic change within the Union (of South Africa – this was before the declaration of the Republic, which came about in 1961).”

The three-hundredth anniversary of the landing of Jan van Riebeeck at the Cape was due to be celebrated on 6 April 1952 and the government planned huge celebrations to mark the occasion.

In response the ANC and its allies initiated the Defiance Campaign, designed to follow Gandhian civil disobedience lines, to protest the growing number of discriminatory laws and regulations under which blacks suffered. By December 1952 more than 8000 had been arrested, 26 Africans and six whites had been killed.

So the horrible events in Nelstroom took place against that backdrop of tension and fear on the part of whites and enthusiasm and anger on the part of blacks.

The specific incident which sparked the riots which form the major part of the novel was the decision by Du Toit to implement the extension of passes to women, who had until then not had to carry them, as was required of all black men. Du Toit called a meeting of the location's residents to announce his decision and it is during this meeting that the confrontation between himself and Mabaso takes place:

“If you don't leave immediately, I'll have you arrested for incitement,” Du Toit says to Mabaso, who has made it clear that he has some questions for which he demands answers.

“I'm not going to stand here and argue with you,” says Du Toit. “If you want to know anything come and see me in my office.”

Mabaso responds: “Oh no, sir. Don't go away. I'm not the only one who wants to know – the whole location wants to know.” The crowd, by now restive and angry, starts to chant “Phendula, phendula (answer, answer).”

This leaves Du Toit with a quandary: “He could not answer: he could not go away. To answer or to go, whatever he did, would be to surrender to Mabaso.” He attempts, and fails, to have his location police arrest Mabaso. Meanwhile the crowd becomes extremely angry and volatile. “He (Du Toit) looked at Mabaso – their eyes exchanged a look. The look in Du Toit's eyes asked Mabaso to restore order, but Mabaso made no move.” At this moment Du Toit perceives himself to be in Mabaso's hands. As the town is locked in a fatal embrace with the location, so Du Toit is locked into his shadow, Mabaso.

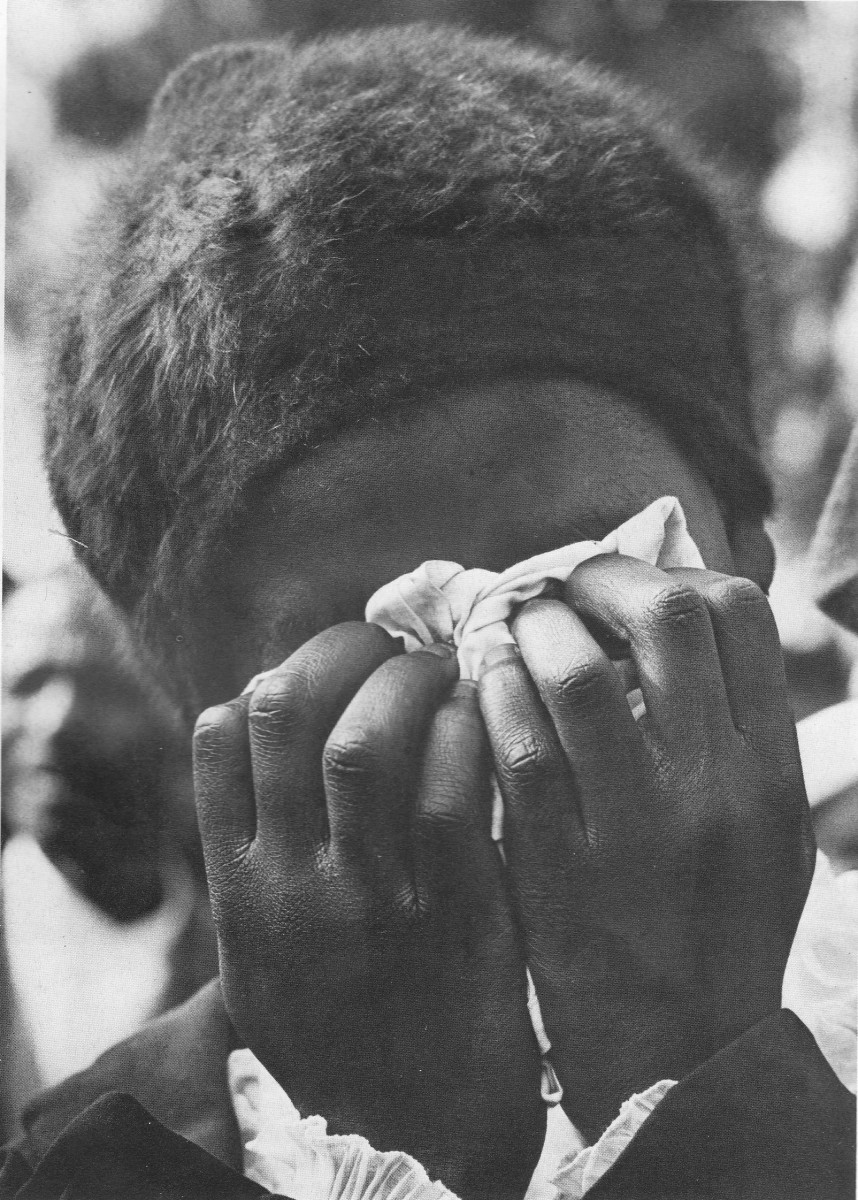

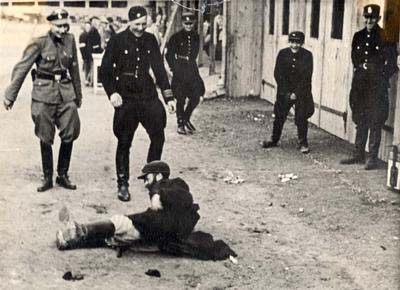

That night, in a sort of panic, the police conduct a “raid,” a house-to-house search of the location, conducted with many random acts of violence on both sides. As a result large numbers of location residents are arrested and taken to the police station in the white town.

Flames engulf many of the houses and other buildings, including the administration offices where Du Toit had worked. Du Toit's career ends in defeat and humiliation, Mabaso's in arrest and death.

A note at the beginning of the novel reads: “1953 was a quiet year. The previous year had been one of upheaval and violence, but in 1953 everything quietened down, as if exhaustion had forced a rest upon the contenders. Nobody had won and nothing was decided, but an hour of uneasy quiet settled on the land. And then the flames leapt up, briefly, in a town called Nelstroom.”

NOTE: Episode was re-issued under the title Transvaal Episode.

Books by Andre Schwarz-Bart

The Last of the Just

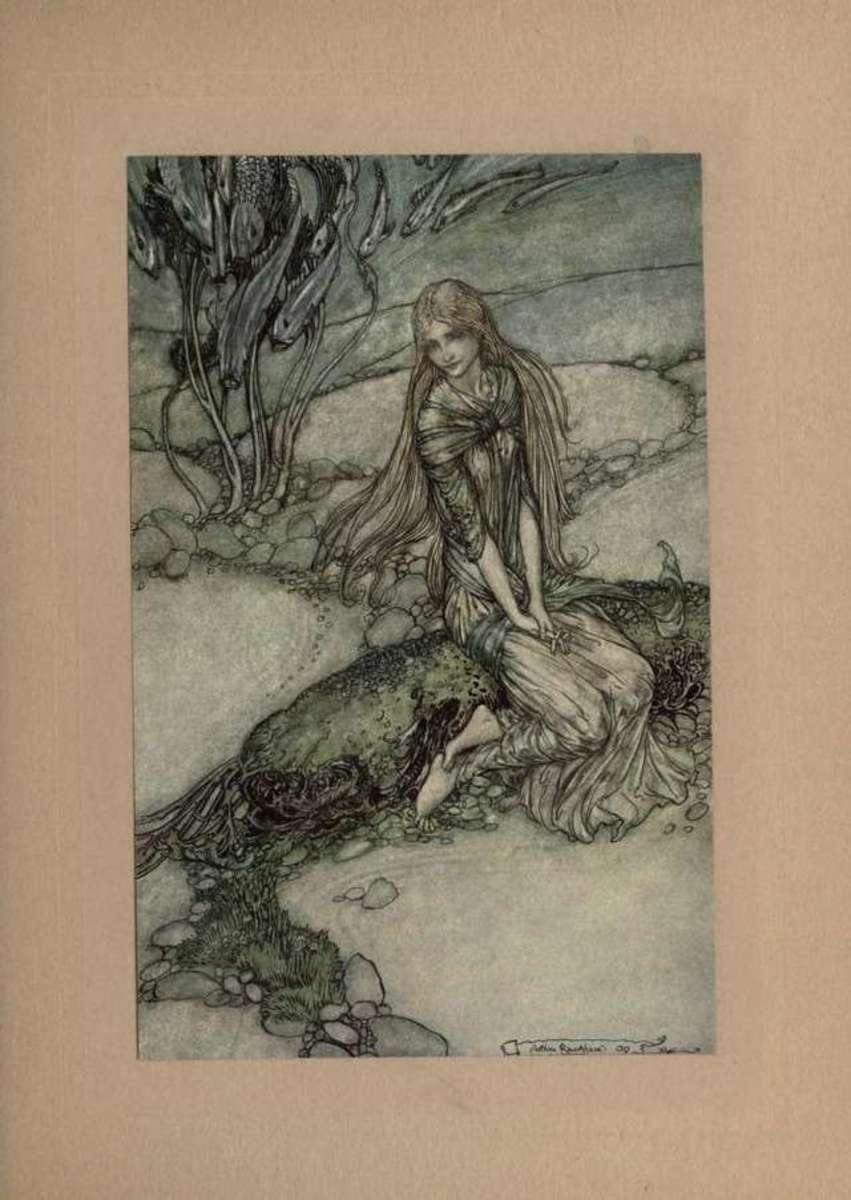

“Our eyes register the light of dead stars.” So opens The Last of the Just . And the novel from the first sentence on is full of death. It's full of life, too, though.

Of course, the reference to “star” is possibly also a reminder of the fact that Jews after about 1938, and certainly in Poland after the invasion in 1939, were required to wear the “yellow star” of identification as a Jew. Unlike the blacks in South Africa, whose difference was obvious, Jews were not that different from the rest of the European population. The wearing of the star made them immediately noticeable, the way a black skin set the oppressed apart in South Africa.

As Jennifer Rosenberg has written in the article “The Yellow Star”: “One day there were just people on the street, and the next day, there were Jews and non-Jews.”

This book tells the story, in the words of an unnamed "friend" of main protagonist Ernie Levy, of the systematic and centuries-long discrimination against the Jewish people in Europe. Schwarz-Bart used the legend of the Lamed-Waf, (Lamed Vav Zaddikim - ל״ו צַדִּיקִים) the 36 “just men” “who are to be found in each generation according to the Babylonian Talmud, upon whom the Shekhinah (Divine Presence) rests, and whose very existence in the world prevents its destruction” (from the Encyclopedia of Judaism), to underpin the history of persecution, starting in “...the old Anglican city of York. More precisely,, on 11 March 1185.”

Other versions of the legend has it that the “Just Men” are isolated and unknown to each other. In Schwarz-Bart's novel they are all part of the Levy lineage, descended from Rabbi Yom Tov Levy, who led his congregation to take refuge in a tower in York after a fiery anti-Jewish sermon by .Bishop William of Nordhouse had incited the Christians of the city who “...moiled through the church square; within minutes, Jewish souls were accounting for their crimes to their God, who had called them to him through the voice of his Bishop.” The Rabbi, after they had spent seven days in the tower, blessed them all and slit their throats, committing suicide himself once all the others were dead.

One baby survived this catastrophe, the Rabbi's infant son Solomon Levy, from whom the protagonists of the rest of the novel are descended.

By the time the Nazis have taken power in 1933, the Levy family is living in the town of Stillenstadt: “One of those charming German villages of a vanished age.” Here Benjamin Levy, father of the final hero of the novel, Ernie Levy, sets up his business as a tailor, marries Ernie's mother, who is known always as “Miss Blumenthal”, and looks after his parents, the patriarch Mordecai and his wife Mother Judith.

In this “charming village” the family comes face to face with the brutality of the Nazis, with their incredible cruelty and pervasive evil.

The nightmare starts to overshadow the family, though they do not always recognise it for what it is – a terminal dream. The patriarch Mordecai especially seems to be unruffled by the gathering forces of doom. An approaching Nazi gang, singing obscene anti-Jewish songs, is approaching, and the patriarch doesn't understand the implications, to Ernie's amazement: “Once more, Ernie was astonished at the calm of the patriarch, who never seemed to be upset about anything that did not bear on the observance of the Law.” Mother Judith is the one who takes charge and gets the family into a neighbour's house and away, for the moment, from the gang.

By the end of the novel Ernie is the last of the family Levy still alive and he too dies in the gas chambers of Auschwitz. The last of the just to die. The world has no more just people – or has it?

“At times, it is true, one's heart could break in sorrow. But often too, preferably in the evening, I cannot help thinking that Ernie Levy, dead six million times, is still alive, somewhere, I don't know where...Yesterday, as I stood in the street trembling in despair, rooted to the spot, a drop of pity fell from above upon my face; but there was no breeze in the air, no cloud in the sky...there was only a presence.”

A presence

I think that presence is the love and empathy of those who say “No” to racism and prejudice, those who say “No” to judgement; those who say an even louder, more emphatic “Yes” to life, to acceptance, to the humanity of all. Perhaps these two books can help us to a deeper sense of our common people-ness, to our essential oneness, across all boundaries and barriers.

Neither book is perfect, and we would be silly to expect perfection from any book. They do however, convey in simple and human terms the ravages of racism, the damage to people caused by prejudice and judgement. This they do in terms which rise on occasion to the poetic, in the sense that the stories and the words provoke profound feelings – at least they did in me – of shame at my complicity in the kind of prejudice which causes such horror, at my lack of courage in facing it in myself, of my judgement of others. Unforgettable, these stories are unforgettable, and no-one should ever forget the two manifestations of racism that were Nazism and apartheid – two of the greatest (though, sadly, not the only) crimes committed against humanity in the 20th Century. May they never happen again. There has been enough sorrow in the world and we need to be more than “mere beasts that talk.”