Learning to Write Fiction

The First Fiction-Writing “How To”

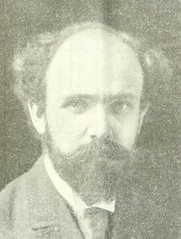

Who was Alpheus Sherwin Cody?

Show, don’t tell. Write what you know. Don’t quit your day job.

Sherwin Cody advised and instructed beginning fiction writers to follow each of those now cliched writing truisms. In his 1894 How to Write Fiction, Especially the Art of Short Story Writing, Cody advocates clarity in writing (perhaps a good excuse for him to drop his first name Alpheus), and claims he can help you shorten the time required to become an experienced fiction writer. Learn how to write your own book. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

The seeds of the emergence of fiction writing guides came about a decade earlier from literary giant Henry James and critic Walter Besant in their 1885 book The Art of Fiction in which they argue that writing fiction was a "trainable art." But of course it took an American, Michigan-born orphan Sherwin Cody to turn the concept into a money maker based on the most extreme form of marketing, lying about who you are (a technique politicians use regularly).

Cody was 26 when he published his instruction book under the pseudonym "An Old Hand" and the publisher boasted that the author was a "well known novelist." In fact, Cody had only a book of self-published poetry called Life’s Philosophy to his credit. While he obviously was not a well known novelist, Cody clearly had the tools to become one, mainly he could lie, and he could lie on a grand scale, pushing ethical boundaries. One could argue that his first book was fraudulent (think James Frey’s "memoir").

Once How to Write Fiction was published, Cody tried following his own advice, but he quickly found out that giving advice, knowing how to write a damn good novel is much more difficult than actually writing it. He was better at giving advice than following his own advice. Cody, having already proclaimed himself a brilliant fiction writer, must have been crushed when his 1896 novel In the Heart of the Hills (fittingly an Hortio-Alger type story) failed. But he must have also learned something about himself.

His next book, The Art of Writing & Speaking the English Language, was published in 1903, seven years after his failed novel. He writes, "You and I were not especially endowed with literary talent... But we want to write and speak better than we do." That sounds like a man who has come to terms with himself. His humorless advice about humor is indicative, "The master of humor can draw upon the riches of his own mind, and thereby enliven any subject he may desire to write upon."

So, while Cody abandoned his hopes of becoming a great writer, he didn’t give up his hopes of helping others become great writers. ("If you can’t live the dream, make a living off the dreams of others.") He compares writing to a trade. "How have greater writers learned to write? How do plumbers learn plumbing?" He asserts that some great writers "who didn’t start with a peculiar genius, have learned to write" like plumbers watching a master-plumber and trying "to do likewise."

For example, this suggestion to copy The Red Badge of Courage. "After reading this passage over a dozen times very slowly and carefully, and copying it phrase by phrase, continue the narrative in Crane’s style through two more paragraphs, bringing the story of this day’s doing to some natural conclusion." The apprentice plumber mimicking the master plumber. I confess to hating these sort of exercises. For me, and I suspect many young writers, something similar happened naturally. I would read a particular writer, then find my own writing sounding suspiciously like theirs. It didn’t take too long to figure out that I was being instructed by the masters.

To be fair, however, Cody wrote just as he advocated -- clear, correct, and colloquial. And his guides were packed with advice and practice still relevant for today’s would-be writers (and copied in countless "How to Write" guides since then). In The Art of Writing & Speaking the English Language, Cody tells the reader to "rewrite this little story, locating the scene in your own home town, and describing yourself in place of" the main character. Many of us have been in classes that give similar instruction, haven’t we? (By the time I eventually took a fiction writing class, I still hated exercises, but saw the potential gain in my participation -- two short stories originated from that class.)

In a way, Cody had what most fiction writers must have today; that is, superior marketing skills. "Traditional" publishers are under siege by hoards of self-publishers (online, ebooks, hard and soft cover) and partly as a result have less and less money to market new authors, pushing more and more new authors into self-publishing. Clearly, new writers need to emulate Cody, become expert advertisers and develop marketing skills (maybe even lie a little?). At any rate, the online world has made all writers advertises of some sort. (Cody might be delighted to know that he’s on Facebook.)

Even though Cody aspired be a fiction writer, he became an entrepreneur, an advertiser, a writer and marketer of business letter guides, business practices, commercial hiring tests, English home-study courses, workbooks, and so on. His last book was published in 1950, Letters: Writing to Get People to Do Things.Perhaps by the time he died in 1959, he knew where he’d failed In the Heart of the Hills, but he’d also got lots of people to do things that made him successful. However, while Sherwin Cody knew how sell his "how to" books, even this master at marketing couldn’t sell his own bad fiction.

Learning to Write Fiction

Thousands of "How to Write Fiction" books have been written, dating back to Sherwin Cody’s 1894 How to Write Fiction, Especially the Art of Short Story Writing. Cody hadn’t published any fiction when he wrote his "how to" book. And two years later, his novel failed miserably. Cody never wrote fiction again. Or at least he never tried to publish his fiction. (In today’s electronic world, he might have tried "self-publishing" on Smashwords or CreateSpace.)

Through his failure, however, Cody discovered something about himself. He was darn good at writing "how to" books. Since Cody’s time, countless successful and not so successful writers have written instruction manuals on how to write. And of course MFA programs abound.

MFA programs at the very least can teach you the basics. The "good ones" cost more, and allow you instruction from "established" writers. But of course there is no guarantee you will learn anything beyond the basics. As in any "profession," learning the literary tricks and infusing passion into your work require you to sell your soul to the devil and endure a lifetime of pain, which is of course hyperbole.

Perhaps the best (and cheapest) approach is to learn from all those how to books. They should at the very least urge you to read either great literature or the books in your niche or genre. (I relived heavily on literature, but of course also read genre novels and guidebooks.) How to guides can help you avoid amateurish errors (professional errors are often hailed as "groundbreaking"), give you a strong foundation to build on, and set you forth on a lifetime of exquisite misery, for there is no misery as grand as the struggling artist, poet, writer.

To build your foundation, you write and write and write and, if you’re lucky, about 2% of it might be good. Hopefully, the more you write and critique yourself and allow others to honestly rip into you, the better writer you will become. Join critique groups, take a workshop or two, give your work to trusted friends, and make sure they understand you want the truth no matter how insulting. Agree with them when they call you a masochist. Avoid the rationalization that your work is as good as the crap published. (So your work is as good as crap?) Above all, show some self-control and avoid self-publishing based on the praise of a few friends and relatives.

A lot depends on your age. If you are 40 or older and you’ve never written a scrap of fiction in your life, then take workshop after workshop, read book after book. You don’t have the time to learn by trial and error. I wasted lots of time avoiding workshops, but I have a convenient excuse -- there weren’t many workshops available at the time and demanding my attention. That makes me sound somewhat intelligent, sort of like a self-taught visionary. Like most of us, I thought I was smarter than I was.

However, to give myself a little credit, masters of any craft have one thing in common -- they start early and "practice" nonstop. While I haven’t mastered all that much, or at least all I need to, I did start early. About ten. Presumably I should have acquired some skills.

Translating your fiction writing skills into commercial success however is a matter of persistence, networking, politics, marketing talent, and pure luck. Expecting commercial success is, as my wife is fond of pointing out, like expecting to win the lottery.

Praised in St. Louis Post-Dispatch

Cover Your Book: How important is the cover?

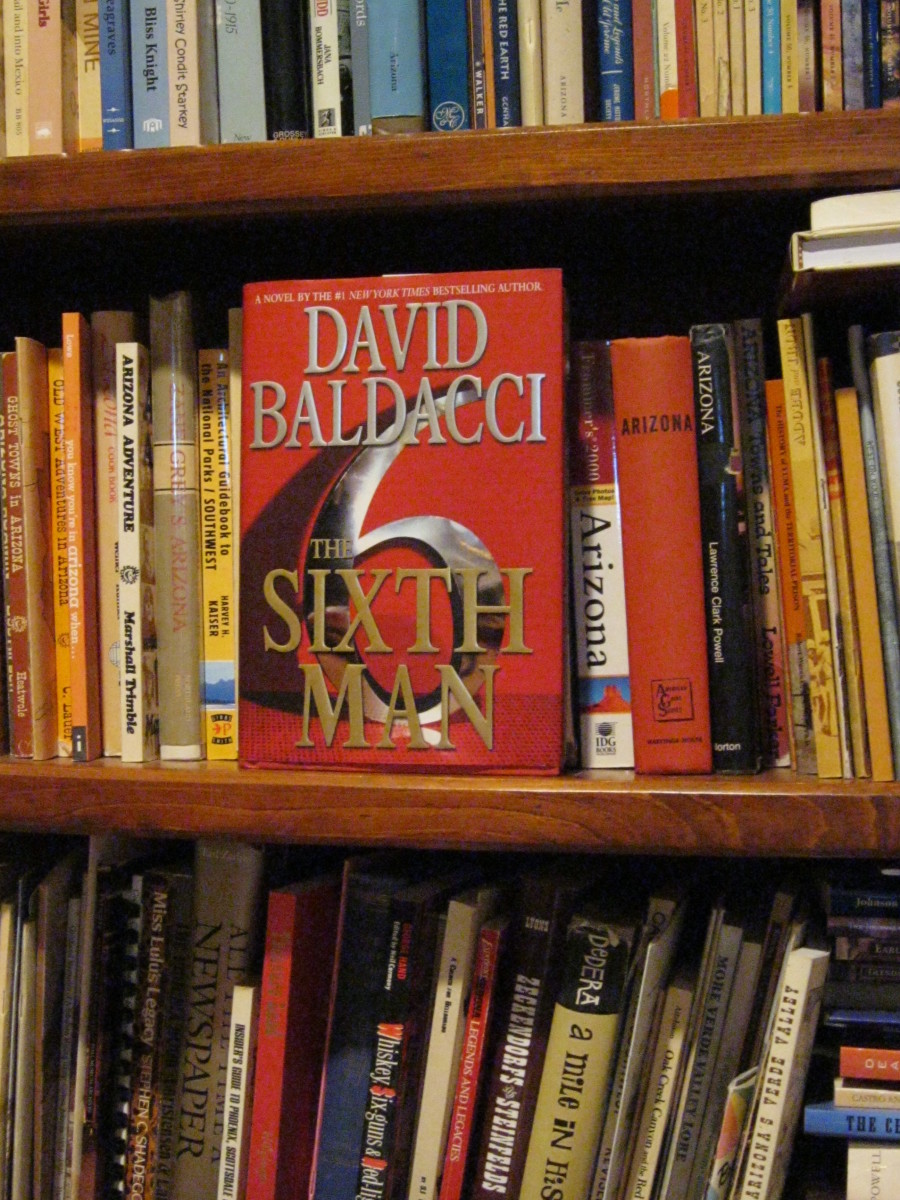

Recently, I read a Huffington Post article by Mark Coker, founder of Smashwords, suggesting that your book cover might need to be upgraded in order to boost sales. This isn’t the first time I’ve read articles extolling the virtues of having an exciting, first class, professional, super expensive book cover. But is it really necessary? What ever happened to the time honored cliché about not judging a book by its cover? Generally, clichés are true, right? I suppose a bad cover can keep me from buying a book but in those cases, usually the entire binding and production process is off-putting and amateurish. And I’m sure there have been times when I bought a book based solely on the cool cover. But I can also remember being disappointed by the ugly prose inside.

While covers are consistently praised for their supposed ability to boost sales, they have also been at or near the bottom on lists for “reasons people buy books.” One study was particularly interesting; I printed it out and pinned it on my bulletin board. Unfortunately, I have no idea where it came from. But the cover was at the bottom of its list. Below “reading group pick.” The two top reasons? Author reputation and personal recommendation.

So before shelling out loads of cash that starving writers don’t have, shouldn’t we ask, “Is an expensive cover a good investment?” Especially when places like Createspace offer covers “free” using theirs or your own photos and art.

So far, except for “Where the River Splits” which came from my publisher, I’ve “created” my own covers. As may seem obvious, they are included here at the bottom, in more or less actual size. I consider them average. Do they inhibit sales? Do the covers merely cover my ass (CYA), or does it convey a sense of professionalism?

Jeffrey Penn May Covers