- HubPages»

- Home and Garden»

- Home Decorating»

- Interior Design & Decor

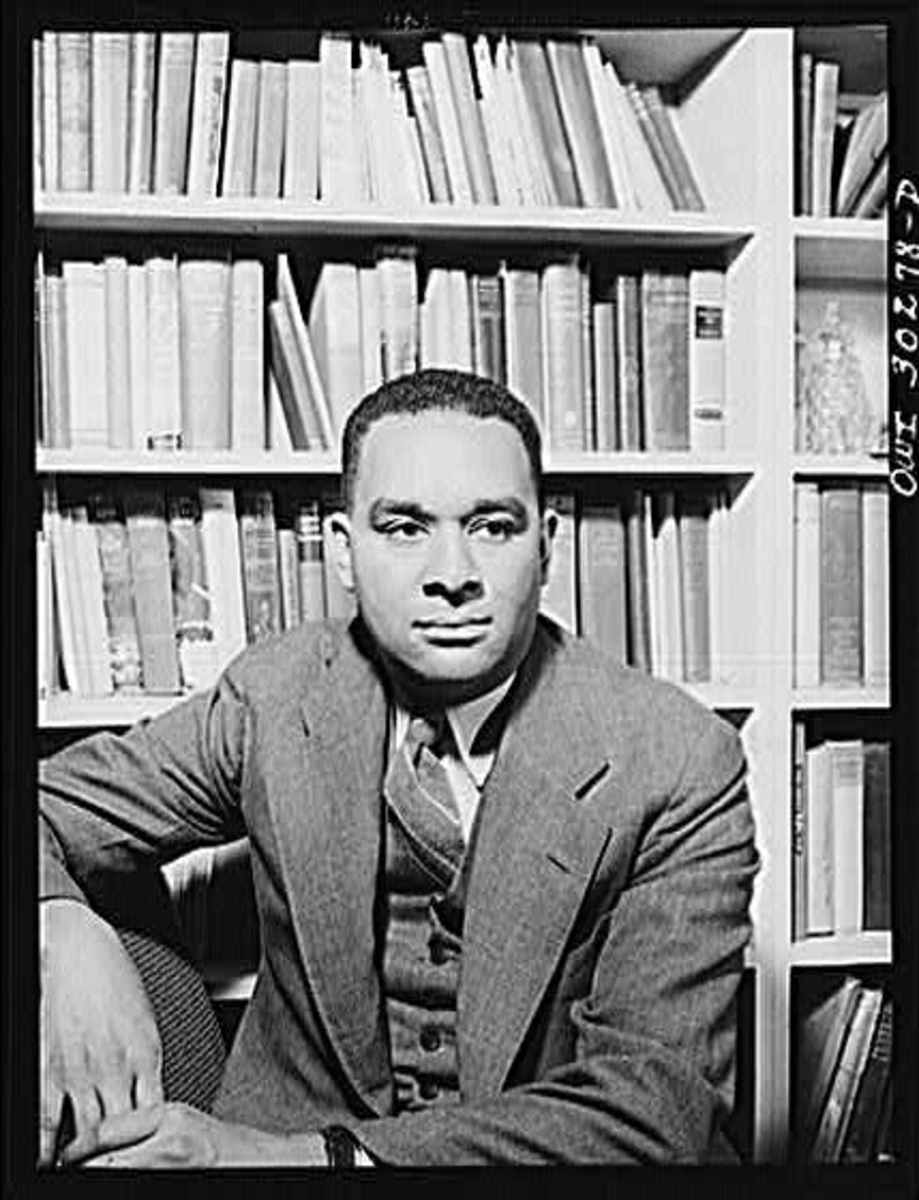

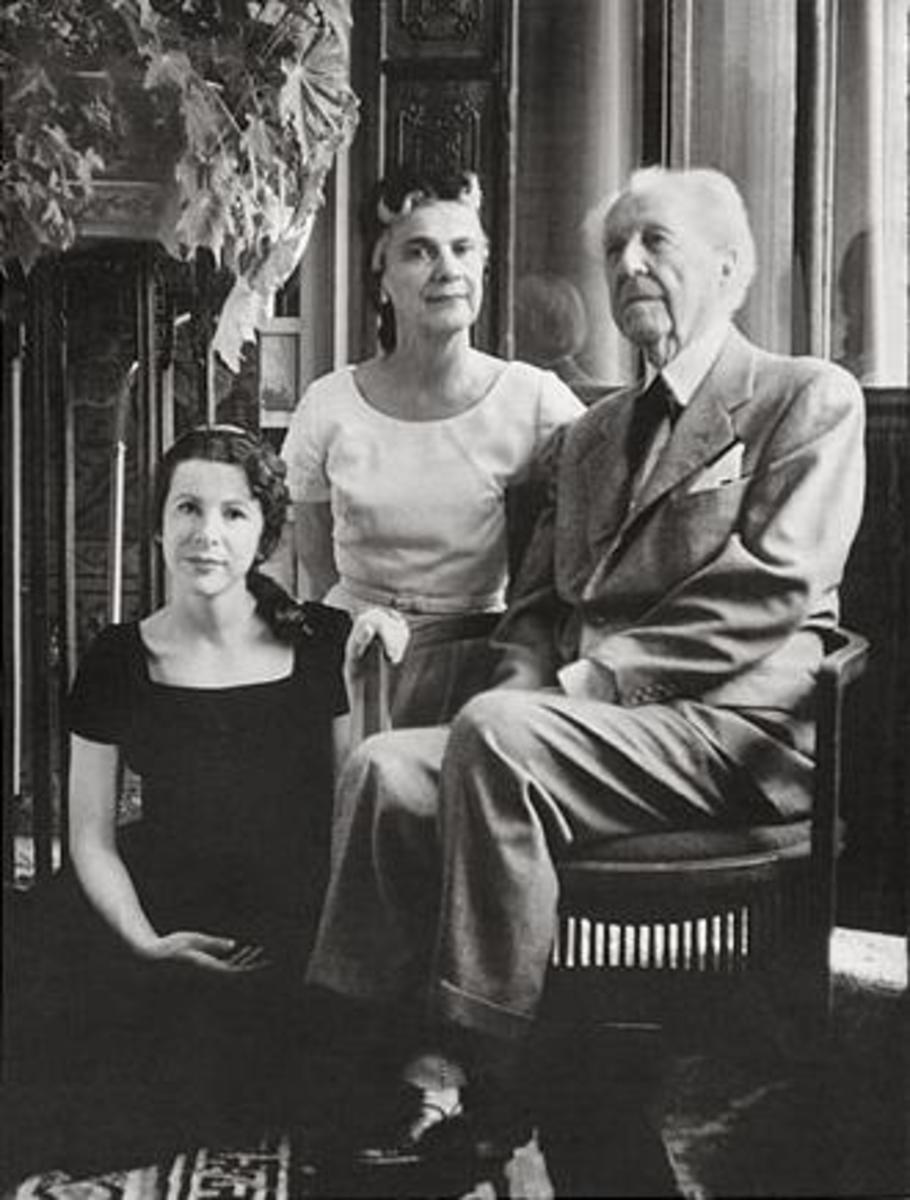

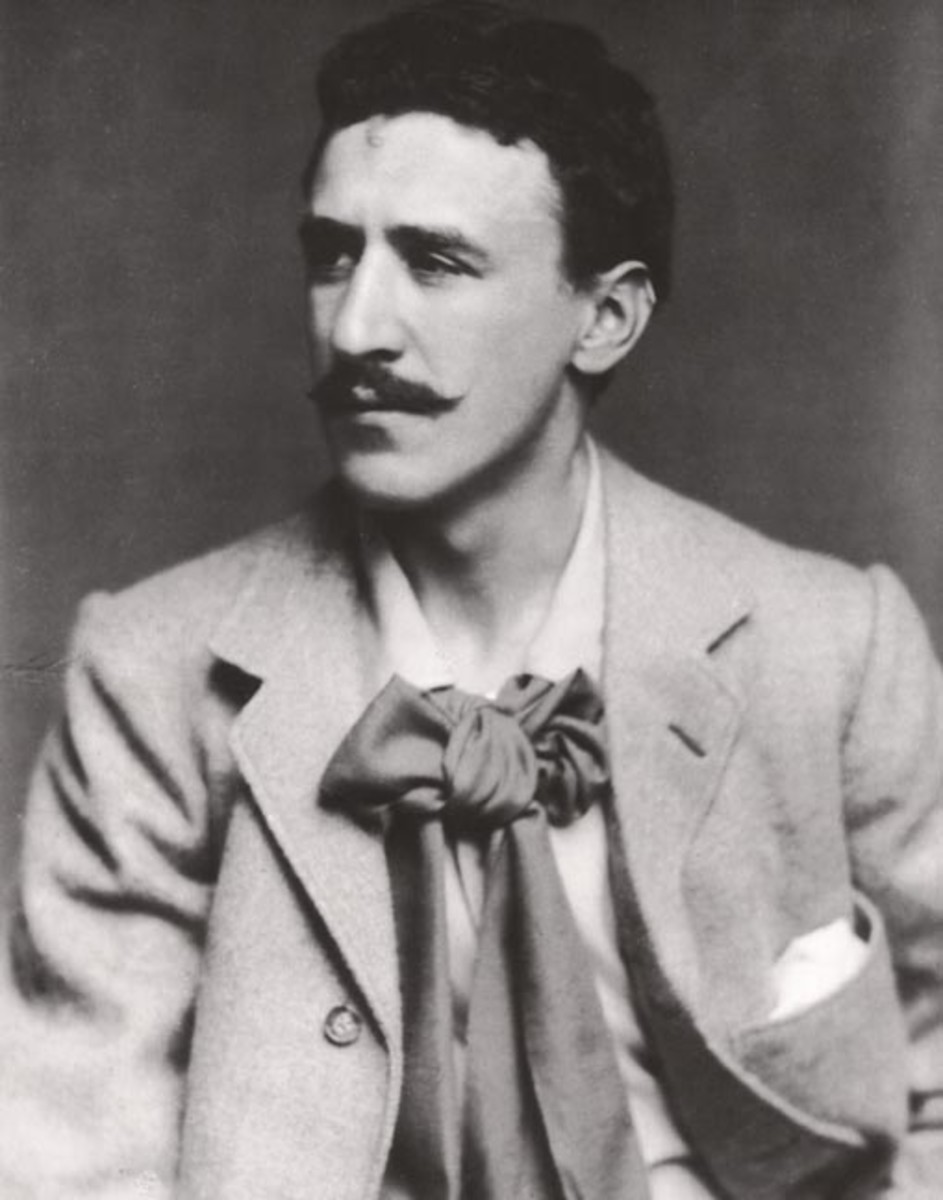

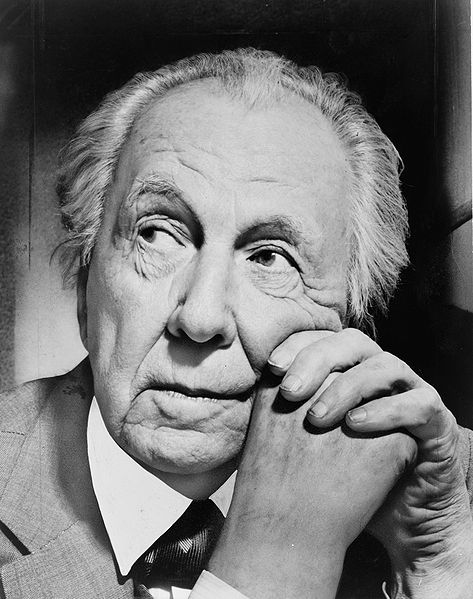

Frank Lloyd Wright: Reverence and Function

Frank Lloyd Wright belongs to the story of Modern architecture; he is an icon and an American great that among the few defined 20th century design. Wright believed as the Bauhaus designers did that in so far as architecture form should follow function and furthermore, that it be accessible to all strata of society. He also aimed to make architecture organic, that it should respond to the environment that surrounds it, and that a designer should find inspiration from nature, the landscape. Wright made use of primary materials but also of manufactured modern materials like cast concrete and Pyrex, and also integrated into his design new technologies like electric lighting. Hence, his philosophy and method reflected a keen awareness of the processes of what was becoming known in the 20th century as industrial design.

From early on, Wright designed homes based on the American way of living in terms of what were really idiosyncraties of 20th century life and certainly also reflective of an American vernacular - he strove to to create an “American architecture" where they had really been none so defined. His Prairie Houses mimicked the landscape of the American Mid-West, ergo the Prairie, with their short proportions and horizontal flow. The Wright aesthetic was ever present: organic adherence, geometric elements, and a reverence to the intended function of a space. In the Prairie Houses, floor plans were open, not segmented. The Robie House in Chicago, built in 1910, is considered the best example of this Wright style. The red-brick veneer exterior stresses the horizontal with its low hipped roof and overhanging eaves, and an open and flowing configuration defines the main floor. Wright's early 20th century designs like the Robie House were discussed in a two volume reference book called “Wasmuth Portfolio” of 1910, and this became a vehicle by which Wright's work was presented to European architects including students of the Bauhaus and the De Stijl school in Holland, who were subsequently influenced in developing their own aesthetic (that would eventually inform Modernism and International Style).

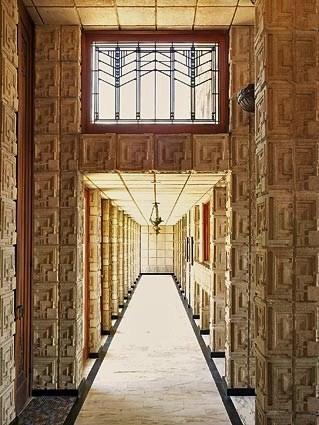

A lull in Wright’s career roughly between 1910 and 1930 was due personal tragedy (a fire and the murder of his wife) but also to a change in popular taste that strayed from the Wright aesthetic. It was also the Depression. Yet this pause was not fruitless and Wright went to work as an architect in Japan. The Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, one that Wright spent designing during his years abroad, was one of the only structures to survive the 1923 Tokyo earthquake. This demonstration of the stalwart nature of a Wright designed building enhanced his reputation as an architect in the U.S and he returned to practice stateside. Settling in Los Angeles, Wright founded a successful practice. Wright's style morphs again with advancement in building materials, and he created what he called the Textile Block Method, in which building walls were made of Wright designed precast concrete blocks textured with brocade-like patterns. Wright designed several homes in southern California using this method including Hollyhock House, Ennis House and La Miniatura, and all three mimic a sort of "Mayan" style, expressed most boldly through the use of the textile blocks. Obviously, these houses are a remarkable part of Wright’s repertoire yet here we see Wright’s novel use of mass-produced and modern materials – he envisioned a socialist style architecture as low production costs using such materials like concrete allowed for affordable housing.

By the 1930s, the momentum of Wright's career slows. He was invited to submit work to the Museum of Modern Art in New York as part of its 1932 exhibit on modern architecture. His application was rejected by MOMA but their exhibit came to include designs from other prestigious Modern architects like Walter Gropius and Mies van der Rohe. The documentary by Ken Burns on Wright's life asserts that he intentionally withheld his best designs because he didn't want to participate in the exhibit, that he was making an intentional and disparaging statement about the emerging Modern architecture that he thought was made up of “soulless cardboard boxes." Ironically, MOMA came to recognize Wright as a corner stone to Modern architecture, his role in the development of International Style and its philosophy that form follows function and that houses are “machines for living,” as Le Corbursier said. Indeed, despite his initial repugnance,Wright came to respect International Style and incorporate the new aesthetic in his own way.

It was after the MOMA event in 1932 that Wright’s career seemed to take a turn into a period in which he would design arguably some of his greatest structures: the Johnson Wax Building, Taliesen West, Fallingwater House and The Guggenheim Museum. He also designed several Usonian houses, a title of his invention referring to some 60 houses similarly styled intended for occupation by middle-income American families. The homes were L-shaped and single storied with flat roofs. Wright’s use of an elongated overhang to create a garage is what he called a “carport,” a word still in use today. The Ranch House, a common type of single story American home, is thought to have originated from the designs of Wright’s Usonian houses.

In building Fallingwater, commissioned in 1935, Wright sought to integrate the beauty as well as native elements of the place into the structure, as the lot was situated in the woods. The home is a mastery of organic design and it presents as Wright intended, built partially over a waterfall and a rock ledge, a central fireplace made with boulders found from the site. The house does reflect in some ways Wright’s fondness for Japanese design in the way that the house effortlessly merges with the landscape (also in the way the Japanese marry interior and exterior, in their open rooms and stark ornamentation): large windows and penetrating views, terraces that project out over the adjacent stream, walls made from quarried local stone. The design of Fallingwater also expresses the bent of International style with its unornamented cantilevers, a plethora of glass with the incorporation of a multitude of windows, with their thin metal frames.

Wright’s place in the history of design was tenuous for much of his career, but so determinedly did he pursue his craft, fueled perhaps by his own arrogance and competitive drive that he was able to reinvent himself like a phoenix from the ashes when he was in his 70s, his career culminating in the building of the Guggenheim Museum that he designed when he was in his late 80s. In the end, he brilliantly merged his early inclination towards romanticism and organic architecture with use of modern materials and an awareness of International Style.