Suicide Prevention: A Global Health Challenge

Suicide: A Health Issue

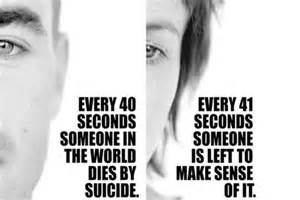

Suicide is a serious public health concern that affects all age groups, including young adults. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2009) deaths from youth suicide are only part of the problem as more young people survive suicide attempts than actually die. The CDC (2009) states “each year, approximately 149,000 youth between the ages of 10 and 24 receive medical care for self-inflicted injuries at emergency departments across the United States” (para. 2).

The topic of suicide can be uncomfortable to discuss with young people and therefore may be excluded from family discussion and formal education. Victims are often blamed while their family and friends are left stigmatized (CDC, 2009). The result is no open communication regarding suicide. The CDC (2009) mentions “an important public health problem is left shrouded in secrecy, which limits the amount of information available to those working to prevent suicide” (para. 5).

Prevent Suicide

Suicide: The Data

Intentional self harm was the 10th leading cause of death in 2010 in the United States (Murphy, Xu, & Kochanek, 2012). It is the third leading cause of death for youth between the ages of 10 and 24 (CDC, 2009). The national 2009 Youth Risk Behavior Survey which sampled a group of students in grades 9 through 12 indicated 13.8% of students seriously considered attempting suicide, 10.9% made a suicide plan, and 6.3% attempted suicide during the 12 months preceding the survey (Eaton et al., 2010, p. 9). Due to these facts, the nation’s public health agenda objectives for Healthy People 2020 include adolescent suicide prevention efforts (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012).

The risk for suicide is apparent for all youth, but some are at a higher risk than others. Karch, Dahlberg, and Patel (2010) state boys and men between the ages of 15 and 19 are five times more likely to commit suicide than females and four times more likely if between the ages of 20 and 24 (as cited in Stanhope & Lancaster, 2012, p. 835). The CDC (2009) mentions that girls are more likely to report attempting suicide than boys. Cultural variations also exist as Native American/Alaskan Native and Hispanic youth have the highest rate of suicide-related fatalities (CDC, 2009). For White, African-American, and Hispanic female youth, the prevalence of attempted suicide is greater (Stanhope & Lancaster, 2012, p. 835).

Suicide epidemiology is important to identify groups such as youth that are at risk. Epidemiology assists nurses to understand the social and environmental factors that affect individual and collective health and disease so that health promotion and disease prevention measures can successfully be implemented (Stanhope & Lancaster, 2012, p. 254). Incidence of suicide is certainly underreported due to religious, social, and other restraints, but risk factors have been identified in youth that can contribute to suicidal behavior. The CDC (2009) mentions several risk factors: history of previous suicide attempt, family history of suicide, presence of depression or mental illness, alcohol or drug abuse, stressful life event or loss, easy access to lethal methods, exposure to suicidal behavior of others, and incarceration (para. 4).

How About You?

Have You or Someone You Know Experienced Suicidal Ideation?

Suicide: What the Literature Says...

For nurses to promote healthy communities and impact concerns such as suicide, nurses must review and evaluate research. Stanhope and Lancaster (2012) state data relevant to changes in health status is valuable in creating the knowledge base for validating the field of community health promotion (p. 458). The School Health Policies and Programs Study is conducted every six years to assess school health programs including suicide prevention (Kann, Brener, & Wechsler, 2007). The study showed that only 55% of states required suicide prevention education in high schools (Kann et al., 2007). Suicide prevention education demands more attention as there is a high incidence of suicide death among youth.

Sise et al. (2011) researched the utility and acceptability of a suicide prevention tool with college freshmen. In the study, 97% of entering freshman at a public university completed a survey of suicidal behavior, help-seeking, and willingness to use a magnet inscribed with suicide warning signs and two prevention services to call for support (Sise et al., 2011). Sise et al. (2011) found 63% of students felt they would call services or the crisis line if someone they knew experienced suicidal thoughts, 82% would encourage the friend to call, while 38% would call for themselves. The study raised awareness about suicide risk signs and symptoms and about counseling services available (Sise et al., 2011).

Public health nurses working on suicide prevention for youth should advocate for educational programs to coincide with prevention tools. King, Strunk, and Sorter (2011) examined the immediate and 3-month effect of a suicide prevention and depression awareness program on students’ suicidality and perceived self-efficacy in performing help seeking behaviors. The researchers conducted a pretest, immediate posttest, and 3-month follow-up test to 1030 high school students following comprehensive and thorough education about depression and suicide using Bandura’s self-efficacy model (King et al., 2011). The program lessened students’ suicidality and activities of sadness and hopelessness while increasing self-efficacy and behavioral intentions toward help-seeking behaviors (King et al., 2011). The study also found that when school-based prevention programs also teach problem-solving and coping skills, reinforce strengths and protective factors, and address risk-taking behaviors, suicide vulnerability may be reduced (King et al., 2011).

Empowering adolescents to lead their peers in lessening the social stigma behind suicidal ideation can also impact the public health nurse’s agenda to prevent youth suicides. Wyman et al. (2010) trained peer leaders from diverse social cliques to conduct school wide messaging to change the norms and behaviors of their peers through activities with adult mentoring. The study improved peer leaders’ adaptive norms regarding suicide, connectedness to adults, and school engagement (Wyman et al., 2010). The intervention also increased perceptions of adult support for suicidal youths and acceptability of seeking help for all students (Wyman et al., 2010).

Quality of instruction is important when teaching health education courses such as suicide prevention. Stanhope and Lancaster (2012) state “health teaching communicates facts, ideas, and skills that change knowledge, attitudes, values, beliefs, behaviors, practices, and skills of individuals, families, systems, and/or communities” (p. 197). Hammig, Ogletree, and Wycoff-Horn (2011) examined the impact of professional preparation and class structure on health content delivery. The study determined professionally prepared health education teachers were more likely to deliver content required in the National Health Education Standards which includes suicide prevention (Hammig et al., 2011).

Prevent Suicide

Why Should I Care About Suicide Prevention?

Youth often experience stress and confusion due to situations in their lives which lead them to consider suicide as the only solution. Suicide prevention programs need developed and implemented due to the growing risk of suicide with age (Pirruccello, 2010). Although public attention and awareness of suicide has increased in the past 20 years, suicide is still the third leading cause of death in the United States for youth 10 to 24 (CDC, 2009, para. 1).

Nurses must participate in the promotion of suicide prevention programs. Stanhope and Lancaster (2012) mention suicide affects the community, the family, and individuals (p. 835). For every suicide committed, there are six people left affected by the event (Eaton et al., 2009, p. 9). Stanhope and Lancaster (2012) state nurses are ideal health care practitioners to lead in health promotion through education since they educate clients across all three levels of prevention and work with individuals, families, groups, and communities (p. 352).

Picking a Target Approach and Population...Pekin, IL

Let's pretend for a minute that we are planning this in my hometown:

The population of interest for implementation of a suicide prevention program is high school freshmen in Pekin, Illinois. Pekin is a town of 34,094 people, 21.9% below the age of 18, which resides in Tazewell County, Illinois (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). Tazewell county’s rate of suicide per 100,000 people in 2002-2006 was 11.6 (Illinois Department of Public Health, 2009). In 2009, the Tazewell County Coroner stated that suicides in Tazewell County had nearly doubled in number (Harris, 2010). High school freshmen are targeted as the entry into high school may pose as a stressful event thus increasing the risk for suicidal behaviors.

The suicide prevention program will be implemented during the health education course required of all Pekin Community High School freshmen. For primary prevention, health teaching must be used to promote protection as primary prevention prevents health threats and promotes health (Stanhope & Lancaster, 2012, p. 191). Since youth spend such a large percentage of each day in school, the school provides ideal opportunities for quality suicide prevention messages (King et al., 2011).

To gain access to the students, the principal of the high school must be notified of the plan. A meeting would be scheduled in which discussion of the issue, data, research, and education would be initiated. Presentation at the next school board meeting may be necessary also. Once the program has been accepted, the high school staff must be notified and educated regarding their role if a student was to approach them with suicidal ideation. The program would then be scheduled within the health education classes, implemented, and evaluated.

Stakeholders must be engaged during the program management. Notification and involvement of stakeholders is the first step in the CDC framework for evaluation in public health (Stanhope & Lancaster, 2012, p. 561). Parents, teachers, students, health department representatives, and school officials will be involved in planning, funding, and implementing the program. The program must then be described and the evaluation design focused (Stanhope & Lancaster, 2012, p. 561). The program’s goals and mission must be evident at this point in the evaluation. Stanhope and Lancaster (2012) mention the next steps include gathering credible evidence, justifying conclusions, and dissemination of findings (p. 561).

Prevent Suicide

Suicide is Forever

Suicide is a serious health concern affecting all populations, especially youth. While gaps in research may exist, professionals must review research and suicide epidemiology to identify and impact this global health issue. Public health nurse professionals can be instrumental in promoting and implementing suicide prevention programs in communities to target populations at risk. Reduction of this health concern is necessary, as suicide is a very permanent solution to a temporary problem.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). Suicide prevention. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pub/youth_suicide.html

Eaton, D., Kann, L., Kinchen, S., Shanklin, S., Ross, J., Hawkins, J., & ... Wechsler, H. (2010). Youth risk behavior surveillance -- United States, 2009. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 59(SS-5), 1-142.

Harris, S. (2010, December 10). Local suicide rate increasing. The Pekin Daily Times. Retrieved from http://www.pekintimes.com/news/x615396257/Local-suicide-rate-increasing?zc_p=0

Illinois’ Department of Public Health. (2009). 2008 Suicide prevention report. Retrieved from http://www.idph.state.il.us/about/chronic/Suicide_Prevention_Rept_2008.pdf

Kann, L., Brener, N., & Wechsler, H. (2007). Overview and summary: School health policies and programs study 2006. Journal of School Health, 77(8), 385-399.

King, K., Strunk, C., & Sorter, M. (2011). Preliminary effectiveness of surviving the teens suicide prevention and depression awareness program on adolescents’ suicidality and self-efficacy in performing help-seeking behaviors. Journal of School Health, 81(9), 581-590.

Murphy, S. L., Xu, J., & Kochanek, K. D. (2012). Deaths: Preliminary data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports, 60(4), 1-68. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr60/nvsr60_04.pdf

Pirruccello, L. (2010). Preventing adolescent suicide: a community takes action. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services, 48(5), 34-41. Doi: 10.3928/02793695-20100303-01

Sise, C., Smith, A., Skiljan, C., Sack, D., Rivera, L., Sise, M., & Osler, T. (2011). Suicidal and help-seeking behaviors among college freshman: Forecasting the utility of a new prevention tool. Journal of Trauma Nursing, 18(2), 89-96.

Stanhope, M. & Lancaster, J. (2012). Public health nursing population-centered health care in the community. (8th ed.). Maryland Heights, MO: Elsevier.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2011). State & county quick facts. Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/17/1758447.html

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2012). Office of adolescent health. Retrieved from http://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/resources-and-publications/healthy-people-2020.html

Wyman, P., Hendricks, B., LoMurray, M., Schmeelk-Cone, K., Petrova, M., Yu, Q., Walsh, E., Xin, T., & Wang, W. (2010). An outcome evaluation of the sources of strength suicide prevention program delivered by adolescent peer leaders in high schools. American Journal of Public Health 100(9), 1653-1661.