- HubPages»

- Travel and Places»

- Visiting North America»

- United States

The French and Indian War and The Deerfield Massacre

We recognize the name Massasoit —if at all—as the Indian chief who celebrated the first Thanksgiving with the Pilgrims in Massachusetts Bay Colony. Squanto, also an Indian, we recall—if at all—for teaching the Pilgrims how to hunt and plant in their new land. But it wasn’t all cranberry sauce and pumpkin pie. Well, probably none of it was.

I use the term Indians not out of disrespect or obtuseness, but because it was the generic term used, however wrongly, at the time, and because it is shorter than Native American , albeit a more accurate term.

In 1621, Massasoit, the great sachem or leader of the Wampanoag Confederacy, whose followers recently had been decimated by disease, forged an alliance, with the English settlers at Plymouth. He and the confederacy helped the Pilgrims survive, but the alliance also promised that neither would harm the other and that they would offer assistance against attackers.

A relationship poisoned

Despite almost constant friction over the settlers’ growing appetite for land (and refusal to surrender Squanto, who was accused of being a traitor), Massasoit observed the treaty until his death. When he was gravely ill in 1623, Edward Winslow, an official from the Plymouth Colony who was the primary author of A Relation or Journal of the Beginning and Proceedings of the English Plantation Settled at Plimoth in New England (which includes his account of the First Thanksgiving),nursed him to health. Massasoit vowed never to forget his kindness.

When the great sachem died in 1661, his eldest son, Wamsutta, who took the English name Alexander, briefly succeeded him. Wamsutta’s relationship with the English was less sanguine than his father’s, and the colonial court in Boston accused him of conspiring with the Narragansett against the English colonists. While in custody, Wamsutta suddenly became seriously ill. He died shortly after his release, amid speculation that he had been poisoned.

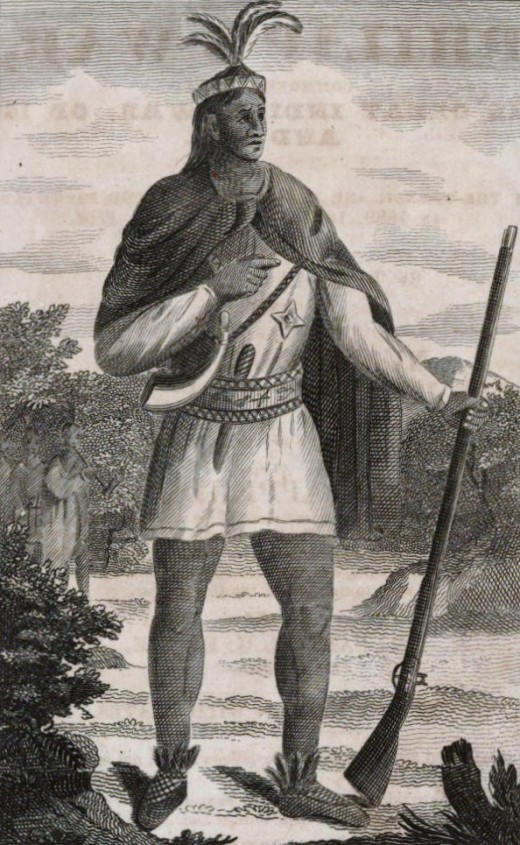

Massasoit’s next eldest son, Metacom, who adopted the English name of Philip, replaced his brother as sachem In 1662, The colonists’ greed for additional land and his brother’s suspicious death were both significant factors in precipitating the brutal campaign that became known as King Philip's War, but it was another event that ignited the uprising.

"Praying Indians" and westward expansion

In his History of the Town of Medfield, Massachusetts, 1650-1886, William Tilden writes that in June 1675, three Wampanoags had been hanged for the murder of John Sassamon, a Christian and Harvard-educated member of their tribe. They had believed that Sassamon had warned white settlers of an imminent Indian uprising. Indian attacks began the day after the Wampanoags were hanged.

A hundred miles west, when a British officer demanded that the local Norwottuck surrender their weapons and submit to British authority, the officer he dispatched, Captain Thomas Lathrop, found that the villagers had fled to join the Pocumtuck Indians, a little less than a dozen miles north on the Connecticut River.

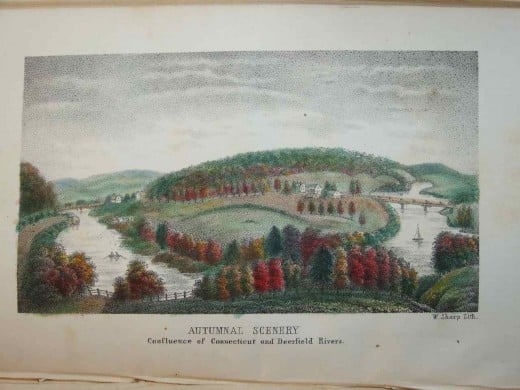

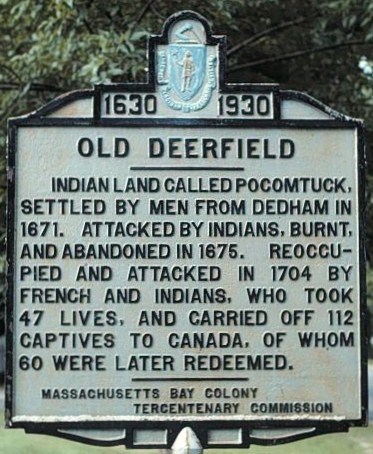

English settlers had first come to Pocumtuck in 1673, after some Nipmunc Indians who had been converted to Christianity set up a community near Dedham, close to Boston. When some of the English citizens of Dedham demanded an equivalent parcel of land to compensate for that the “praying Indians” were occupying, they received a charter to settle on a square mile of Pocumtuck land they called Deerfield at the confluence of the Connecticut and Deerfield rivers.

King Philip's War

In July, Metacom joined with the French to fight the English colonists in what was called Metacom's Rebellion, or King Philip's War.

On September 1, 1675, the same day that the Angel of Hadley helped repulse the attack on the Hadley congregation about a dozen miles south and seventeen days before the Bloody Brook, the Indians attacked Deerfield village, burning several houses and killing one of the settlers. After the settlement was burned to the ground in a second attack later that year, the English settlers abandoned the settlement.

By summer’s end, the Nipmucks and even the Wampanoags’ traditional foes, Rhode Island's Narragansetts, had joined the campaign. By November they had retaken the upper Connecticut Valley, and the Norwottuck and Pocumtuck returned to Deerfield and resumed farming. In May of the next year, 1676, the English settlers attacked while they were at their fishing village at Peskeompskut (now Montague), killing hundreds.

The war ended that year, about 14 months after it had begun, but Metacom did not get out alive. When killed one of his men for advocating surrender, the man’s brother told the English where to find the Indian camp. The English encircled the encampment, and, when Metacom tried to break out, he was shot through the heart—by the man whose brother he had killed for advising him to pack it in.

The angry settlers quartered Metacom's body, and displayed his severed head on the village green at Plymouth for years after. His family was sold into slavery.

The war devastated the Massachusetts Bay colonists. More than a dozen towns and close to 1,200 homes were destroyed. At least 600 of the English men and well over three times as many of their women and children were killed. But for the Indians, it meant almost total destruction, leaving only a few small villages scattered through the colony.

The Deerfield Massacre

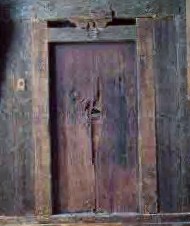

The English resettled in Deerfield in 1682. In 1690, they erected ten-foot palisades around eleven homes. But during Queen Anne’s War, or the War of Spanish Succession, two-dozen years later, Deerfield suffered its most devastating attack, remembered as the Deerfield Massacre.

Early in the early morning of February 19, 1704, French soldiers led 200-300 Indians from more than a half-dozen tribes to attack the English settlers at Deerfield, where a deep accumulation of snow allowed them to scale the palisades. Among the Mohawks who participated in the raid were two women, charged with selecting captives to be adopted as family members to replace children who had died. The attackers killed 43 settlers and 5 soldiers, (some reports give slightly higher numbers) and took 111 men, women, and children captive. .Those who died in the attack are buried in a mass grave in the Old Burying Ground just off Deerfield Academy’s campus.

Most of the surviving English women and children were sent to safety in settlements farther south in the Connecticut Valley, with about two dozen men staying behind in Deerfield

Over the next two months, the Indians and their French allies marched their captives about 300 miles, to Montreal in New France. Nearly two-dozen captives died on the trek, including many injured women and children who were killed because they could not keep up. When they reached Montreal, The captors divided the prisoners among them.

Epilogue

n 1707, Governor Joseph Dudley, ransomed the 60 surviving captives, among them the Reverend John Williams, who maintained that the attack was divine retribution for weak faith among his congregation. He wrote “The Redeemed Captive Returning to Zion,” about his experience.

The minister’s daughter Eunice was among a number of captives who chose to remain with their Indian families. Her adoptive mother had treated Eunice—who would later marry a Mohawk—as if she were the daughter she had lost to smallpox.

Rev. Williams’ journals and letters make clear that, even those who chose to return to Deerfield had developed close bonds with their captors, many of whom, including his, made repeated visits to their former captives, who treated them as honored guests.

For the most part, the English colonists never seemed to understand their culpability in driving the Indians to desperation as their lands were being eaten up by their expansion, or the role of the French during the French and Indian Wars, who were likely motivated by fear of losing their trading partners as much as they were by politics.