The Rise and Decline of Electric Vehicles

Considering how primitive the means of transportation was centuries ago, it is such a wonder how modern vehicles came to be. Especially if you study how electric vehicles work, it is truly amazing how all this came from scratch. True to any invention however, it all starts with one great idea that transforms into a reality.

The Earliest Models and Actual Vehicles

The dream to create vehicles that run on electric power did not come from a single mind. Various people contributed to the concept, although it was Anyos Jedlik, a Hungarian inventor, who first came through with an actual model car. In 1828, he invented a simple type of electric motor and used it to power up a small model car. Thomas Davenport, a blacksmith, followed up the idea a few years later in 1834 when he built a similar model which ran around an electrified track. A year after that, Professor Sibrandus Stratingh and Christopher Becker used primary cells to power up a small electric car.

In 1837, a chemist from Aberdeen named Robert Davidson built the first electric car powered by batteries. Later on, he used the same science to build a locomotive which he called Galvani. Weighing 7 tons, its test run was done on the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway, although its general use was not seen to be possible because of the limited power that its batteries gave. Despite this fact however, railway workers were threatened by the thought of having a working electric locomotive and destroyed it to make sure that their employment remains secure.

A British inventor named Robert Anderson also contributed to the science that was being developed, building an electric carriage between 1832 and 1839. In 1840, a patent was finally released in England for using rails as a source of electric current. In the US, a similar patent was granted in 1847.

The Earliest Practical Electric Cars

One thing that remained to be a hindrance to building an actual functional electric vehicle is the source of power. It was not until 1859 when the idea of using rechargeable batteries was raised when Gaston Plante, a French physicist invented the lead acid battery. However, the capacity of these batteries was still not enough to power an entire vehicle effectively. The battery design was then enhanced by Camille Alphonse Faure, also a French scientist, significantly increasing the battery’s capacity to supply power.

A few other electric vehicles were invented after this, but were mostly for display purposes. Franz Kravogl, an Austrian inventor, created an electric two-wheeled cycle that was exhibited at the World Exposition in Paris in 1867. A three-wheeled version was made by Gustave Trouve, a French inventor, which was exhibited in the International Exhibition of Electricity in 1881, also held in Paris.

It was in 1884 that the first practical electric car was finally built by Thomas Parker, an English inventor. He was also responsible for enhancing the London Underground to make it electric-powered, as well as the tramways in Birmingham and Liverpool. He used his personal design on rechargeable batteries to give it the capacity that it needs to power such vehicles. His inventions were also partly due to his advocacy to minimize the effects of pollution by coming up with more fuel-efficient alternatives.

The Start of Commercial Production

In 1882, the Elwell-Parker Company was established to initiate the production and selling of electric trams. It eventually merged with other similar companies to form the Electric Construction Corporation in 1888, helping it monopolize the electric car market in the United Kingdom. The country, along with France, was the very first who supported and pushed for the continued development of the market. Germany closely followed suit when their first electric car was built in 1888 by an engineer named Andreas Flocken.

One of the major roles that electric trains played was in transporting coal out of the mines. This because helpful in the industry mostly because of the fact that it did not use up what little amount of oxygen was inside the mines.

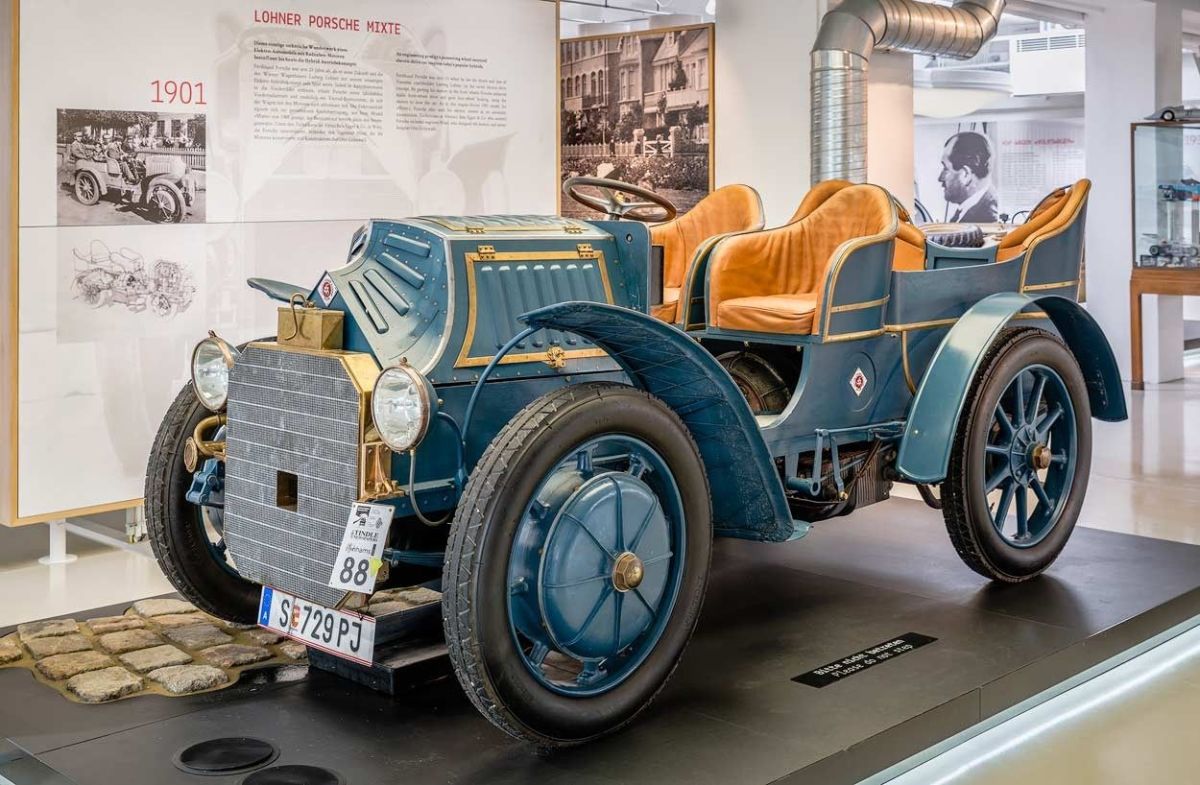

The designs of electric vehicles continued to be enhanced and improved as inventor after inventor aimed to build a better vehicle than the last. An example was Camille Jenatzy’s rocket-shaped car, which he named Le Jamais Contente. It was the first that broke the 62 mph (100 kph) mark, reaching a top speed of 65.79 mph (105.88 kph). Ferdinand Porsche’s design also contributed greatly in the development of electric cars, with his all-wheel drive vehicle also breaking and setting a few records of its own.

The Growth of the Electric Car Market

It was William Morrison from Des Moines, Iowa that finally created America’s first electric vehicle. It was a wagon that carried up to six passengers and reached a speed of 14 mph. Americans eventually took notice of electric vehicles when A.L. Ryker introduced them to the first electric tricycles in the country in 1895. By this time, Europeans have already been using electric vehicles for around 15 years.

In the 1897, electric taxis hit the streets of London. These battery-powered cabs roamed the streets of London with their signature humming sound, which was why they were eventually known as “hummingbirds”. New York City also rode with the trend and started running 12 electric cabs by Samuel’s Electric Carriage and Wagon Company. It was eventually reformed as the Electric Vehicle Company in 1898, a point when the company already had 62 cabs operating.

A gasoline-electric car was introduced in 1911 by the Woods Motor Vehicle Company in Chicago, but it was expensive, slow, and difficult to maintain. Electric cars remained to be the popular choice despite the slow speeds, considering that it did not have the same noise, vibration and smell that gasoline cars were notorious for. It was also easier to start an electric car, as a gasoline-powered one needed a hand crank for the engine to start, taking up too much effort.

Electric cars became known as city cars considering that the range they were limited to did not matter much in a city setting. It was also eventually considered as a woman’s vehicle because it was easy to use and operate.

In 1912, home after home started being wired for electricity, which caused the electric vehicle market to boom. Although the science started in the UK, it was the US that proved to have accepted the trend the most. There were a lot of electric-powered carriages that became known for their elaborate designs and luxurious interiors, often used by the upper-class.

The Decline of the Electric Vehicle Market

In the 1920s, road infrastructure was greatly improved, introducing the need for vehicles that had a higher range. It was also a period when massive petroleum deposits were being discovered all over the world, making gasoline the cheaper option especially for long distances.

Charles Kettering eliminated the need for a hand crank to start gasoline-powered vehicles when he invented the electric starter in 1912. Hiram Percy Maxim also invented the muffler in 1897, which greatly decreased the noise that these vehicles gave out. Henry Ford also started mass production of gas vehicles, bringing their prices down. In contrast, the price of electric vehicles rose at a steady pace. All these contributed to the decline of the electric vehicle market. Around 1910, electric vehicles were only manufactured and sold for specific applications such as milk floats and golf carts.

The electric vehicle market definitely had a good run. At the end of the day however, the masses chose practicality and range and made the gasoline-powered cars the better options until today.