- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- Life Sciences»

- Paleontology»

- Prehistoric Life

Dinosaurs of the Year: 2018 Edition

2018 had a crowded but uneven field of new dinosaurs: There were enough new sauropods and theropods described (i.e. officially named and announced to the general public) for each to have their own end-of-year retrospective articles. In contrast, there were surprisingly few new ceratopsians, hadrosaurs, or other ornithischians named this year (though there were seven new ankylosaurs).

Therefore, the most important new dinosaurs of 2018 were three sauropods and three theropods, albeit with a longer than usual list of honorable mentions.

Ingentia and Ledumahadi

(Argentina and South Africa, 210-205 million and 200-195 million BCE -- "before the common era"; same dating as "BC")

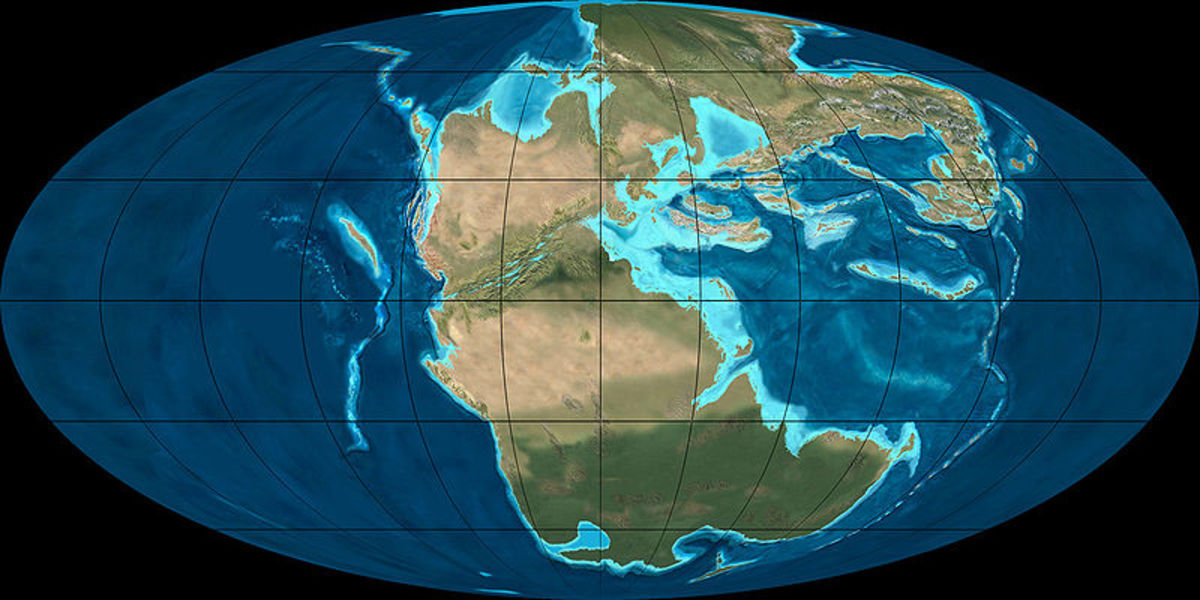

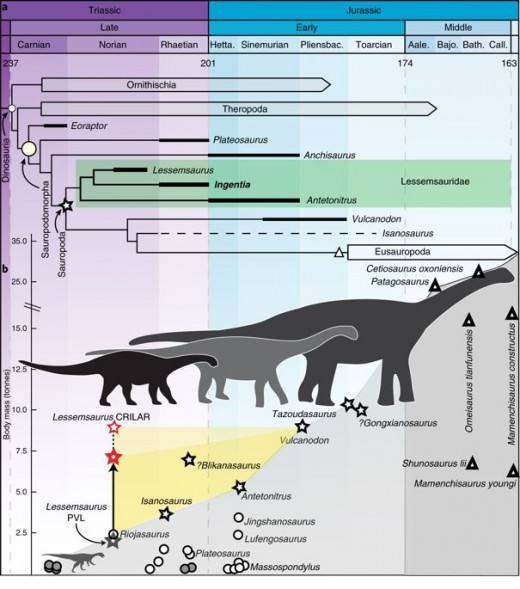

The earliest confirmed dinosaurs emerged in the middle of the Triassic Period (252-201 million BCE). The first sauropods appeared during the last ten million years of this period, diverging from less specialized, mostly bipedal sauropodomorphs (sauropods and their close relatives) like Plateosaurus.

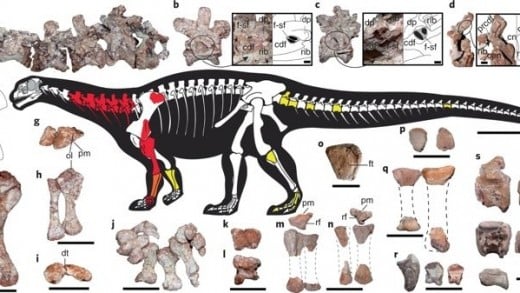

Ingentia (“huge one”) roamed northwestern Argentina between 210 and 205 million BCE, and measured up to 33 feet long and 11 tons. Though measly by the standards of later sauropods, these figures represent a quantum leap for dinosaur size during the Triassic. Most of the dinosaurs of this period, carnivore and herbivore alike, had to compete for resources with older reptile lineages such as the rauisuchians and the dicynodonts (the largest of which, the 9-ton Lisowicia, was also described this year). To date, however, Ingentia is biggest known dinosaur — and land animal — of the entire Triassic Period.

Ingentia was not a “missing link” between more primitive sauropodomorphs and more advanced sauropods, but had certain similarities to each: Like other sauropods, it was too bulky to walk on only its hind legs. Based on growth rings in its bones, however, Ingentia grew on a sporadic, seasonal manner similar to earlier sauropodomorphs. Most strikingly, however, Ingentia and its closest relatives were extremely stocky and bowlegged, walking in a more crouched position than more columnar-limbed giants like Diplodocus or Brachiosaurus.

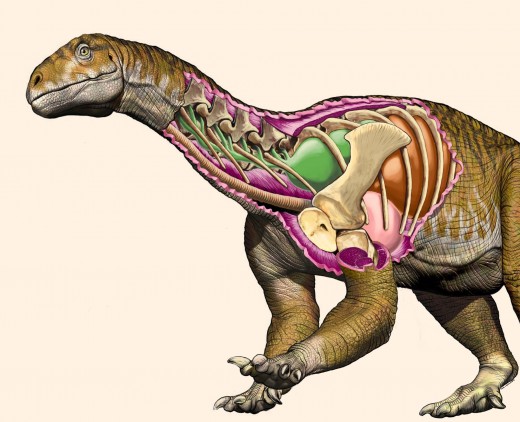

Ledumahadi (“giant thunderclap”) dwelt in South Africa’s Free State about five to ten million years after Ingentia and grew even bigger — up to 13 tons. It, too, was the largest animal on land at the time but lacked the more upright gait of later sauropods. By the beginning of the Jurassic Period (201-145 million BCE), a volcanically-driven mass extinction had wiped out most of the dinosaurs’ competitors from the Triassic. The presence of similar, even larger dinosaurs like Ledumahadi just after this cataclysm is a testament to the resilience of these animals.

It should be noted that several news stories about both Ingentia and Ledumahadi stopped short of calling them sauropods, since the boundary between true sauropods and other sauropodomorphs isn’t universally agreed upon by experts. Yet the five Argentine paleontologists who described Ingentia also coined the lessemsaurids, a new sauropod family to encompass both Ingentia and Ledumahadi, as well as the earlier-described Antetonitrus and the group’s namesake Lessemsaurus (named, in turn, after science writer and dinosaur exhibitor Don Lessem). Even if this new group’s status as sauropods is disputed or eventually rejected by most paleontologists, the lessemsaurids have the distinction of not only reaching huge size before any other dinosaur group, but also doing so independently of the sauropod line that produced Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus, and countless other giants.

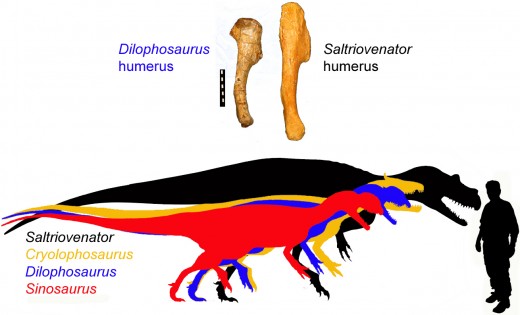

Saltriovenator

(Italy, 199-197.5 million BCE)

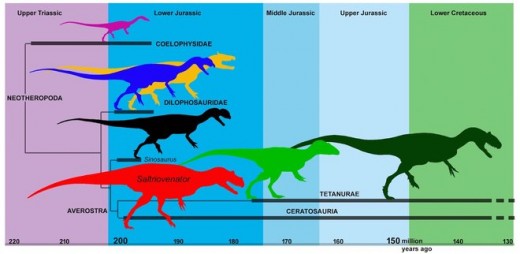

As the sauropods grew larger throughout the Jurassic Period, so too did the theropods, the group that includes the vast majority of meat-eating dinosaurs. These animals were lower-to-middle tier predators during the Triassic, and after the extinction event that wiped out their non-dinosaurian competitors at the end of this period, they began to grow larger than any living terrestrial carnivores.

Saltriovenator (“hunter from Saltrio”) is now the largest of these early super-predators. As of writing, it is known from 132 bone fragments from a single sub-adult individual, including pieces gnawed upon by marine invertebrates after the animal died and floated out to sea. Over 200-odd million years, the dinosaur’s skeleton was further ravaged not only the formation of the Italian Alps but also dynamite used at the marble quarry where it was discovered. Nonetheless, enough pieces of the Saltriovenator’s skeleton survived to indicate it was an exceptionally large theropod for its time. The paleontologists who described this dinosaur estimate that it reached around 25 feet long and one ton in weight, dwarfing other big theropods of the Early Jurassic.

This predator is also only the third dinosaur known from Italy thus far and the oldest member of the ceratosaurs (“horned lizards”). The ceratosaurs evolved outside of the line that produced Allosaurus, T. rex, and birds and survived as late as 66 million BCE, when they and all other non-avian dinosaurs went extinct.

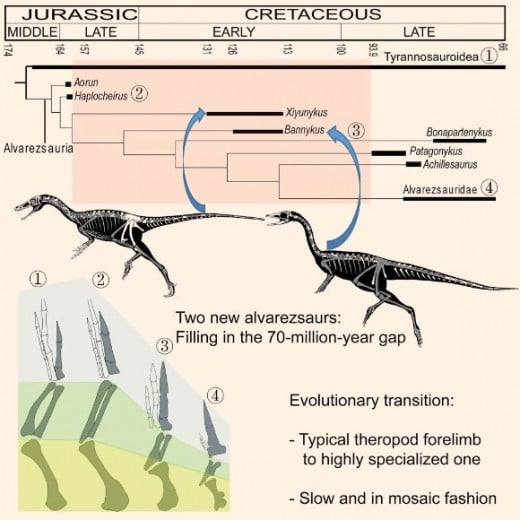

Xiyunykus and Bannykus

(China, 131-113 million BCE)

The alvarezsaurs are among the most bizarre dinosaur groups, as well as one of the least publicized. Distant relatives of both tyrannosaurs and birds, these theropods were nimble, long-legged animals typically less than six feet long. Most of the later alvarezsaurs had long, narrow snouts and stunted arms tipped with enormous claws. Many paleontologists have suggested that the alvarezsaurs were the anteaters and aardvarks of their day, using their jaws and claws (and maybe even long tongues) to raid termite nests.

This year, scientists described two important new alvarezsaurs from the Early Cretaceous Period (145-100 million BCE) of China. Xiyunykus (“claw from western central Asia”) and Bannykus (“half claw”) both lived around 120 million BCE and were about five feet long.

Xiyunykus seems to have resembled earlier alvarezsaurs like Haplocheirus and even distantly-related small theropods like Velociraptor, with long arms ending in three-fingered hands and a neck only slightly longer than its skull. The slightly later Bannykus, on the other hand, had shorter arms and a longer neck, as well as probably a smaller, narrower skull. And though Bannykus still had three fingers on each hand, the inner digits were significantly longer than the other two. Much later, more specialized alvarezsaurs had would take this adaptation to new extremes, developing huge-clawed thumbs which made up most of the hand while the other two fingers were reduced to tiny stubs, if not absent altogether.

Together, Xiyunikus and Bannykus start to bridge a 70-million gap between early and late alvarezsaurs, providing key snapshots in their transition from generic small theropods to some of strangest, most specialized dinosaurs of all time.

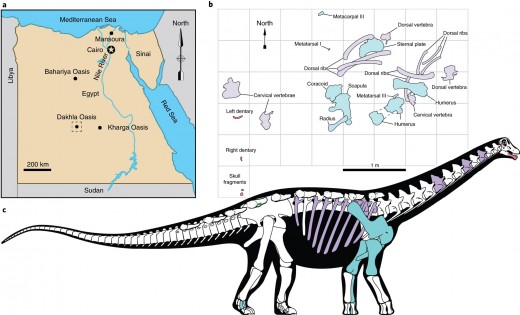

Mansourasaurus

(Egypt, c.80-73 million BCE)

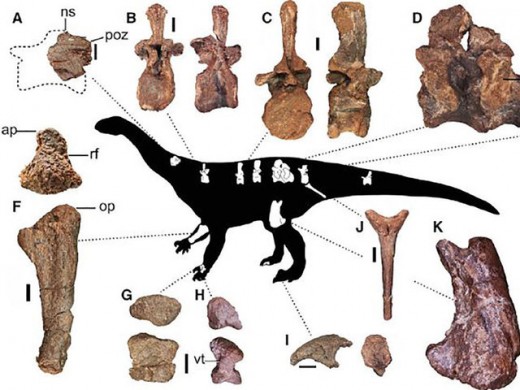

By the Late Cretaceous Period (100-66 million BCE), the only living sauropods left were the titanosaurs. These sauropods include most of the serious contenders for the title of biggest dinosaur and are particularly well-represented in Late Cretaceous bone beds in South America. Their history is a lot less clear in other parts of the world, however, such as North America, Australia, and Africa (though Rapetosaurus, one of the titanosaurs with the best-preserved fossils, lived in Madagascar).

Mansourasaurus (“Mansoura University lizard”) is now the most complete sauropod — and dinosaur — known from the mainland of Late Cretaceous Africa, a time and place with a fairly patchy record of dinosaur fossils. In 2016, a team of American and Egyptian paleontologists discovered multiple specimens of this titanosaur in the Dakhla Oasis, including ribs, shoulder and arm bones, and even fragments of the skull — a part of sauropod skeletons usually too small and delicate to survive fossilization. Astoundingly, the most complete Mansourasaurus specimen was about the same length yet half the weight of the much older Ingentia (though some the animal’s front leg bones were not fully fused, indicating that their owner was still growing when it died).

Another surprise is that Mansourasaurus seems to have been more closely related to titanosaurs from Europe than any discovered in South America thus far. South America and Africa were connected during the Triassic and Jurassic Periods, producing similar dinosaurs on each continent. By the mid-Cretaceous, however, the African mainland was an island continent. Mansourasaurus is not only an ambassador from a hazy chapter in fossil history of Africa, but also an indication that this region was more connected to the rest of the planet than one might expect.

What was the most important dinosaur described in 2018?

HONORABLE MENTIONS

Acanthopilan- Nodosaurine ankylosaur from Late Cretaceous Mexico.

Akainacephalus- Ankylosaurine ankylosaur from Late Cretaceous Utah.

Arkansaurus- Early ornithomimosaur from Early Cretaceous Arkansas.

Bagualosaurus- A primitive sauropodomorph from mid-Triassic Brazil.

Caihong- Anchiornithid theropod preserved with iridescent feathers, a feature it evolved before and independently of birds.

Choyrodon- Hadrosauroid from Early Cretaceous Mongolia.

Crittendenceratops- Centrosaurine ceratopsian from Late Cretaceous Arizona. It was rather small by ceratopsian standards, measuring about the same length and weight as a cow.

Diluvicursor- Basal ornithopod from Early Cretaceous Australia.

Dynamoterror- 30-foot-long tyrannosaur from Late Cretaceous New Mexico.

Invictarx- Nodosaurine ankylosaur from Late Cretaceous New Mexico. It lived at the same time and place as Dynamoterror.

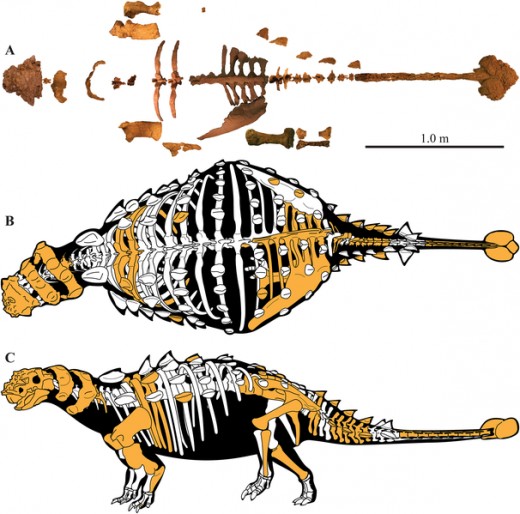

Jinyunpelta- Earliest known ankylosaur with a tail-club, from mid-Cretaceous China.

Lingwulong- The oldest-known dicraeosaurid, as well as the first known diplodocoid from Asia.

Macrocollum- The earliest-known long-necked, herbivorous sauropodomorph, from mid-Triassic Brazil.

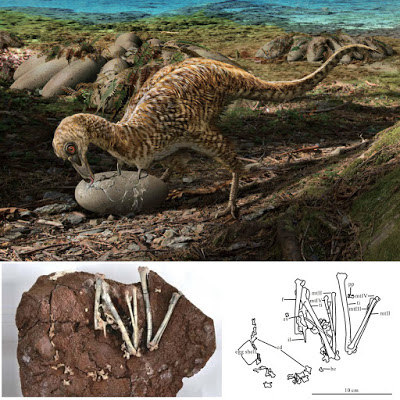

Qiupanykus- A third Chinese alvarezsaur described this year, this time dating from the latest Cretaceous. It may have been a nest raider, since its bones were found in close association with other dinosaur eggs (ironically laid by an oviraptorosaur, a name which means “egg-thieving lizard”).

Tratayenia- Late, large megaraptoran from mid-Cretaceous Argentina.

Volgatitan- Advanced titanosaur from Early Cretaceous Russia and the oldest-known titanosaur from the Northern Hemisphere.

Weewarrasaurus- Basal ornithopod from mid-Cretaceous Australia whose bones were opalized in the process of fossilization.

Yizhousaurus- Primitive, short-skulled sauropod from Early Jurassic China.

RENAMED DINOSAURS

Maraapunisaurus- A renaming and re-description of ”Amphicoelias fragillimus”, a candidate for the largest known dinosaur known from a single giant, now-lost vertebra. Paleontologist Kenneth Carpenter reinterpreted the animal as a rebbachisaurid instead of a diplodocid. If correct, then Maraapunisaurus is the oldest and largest known rebbachisaurid, as well the first one known from North America.

Platypelta- Ankylosaur from Late Cretaceous Alberta whose bones were formerly assigned to Euoplocephalus.

SOURCES

“Akainacephalus johnsoni: New Armored Dinosaur Species Discovered.” Sci-News.com, 6 Dec 2018.

Apaldetti, Cecilia, Ricardo N. Martinez, Ignatio A. Cerda, Diego Pol, and Oscar Alcober. “An early trend towards gigantism in Triassic sauropodomorph dinosaurs.” Nature, 9 July 2018.

Brantley, Max. “The Arkansaurus dinosaur is officially official.” Arkansas Times, 19 Mar 2018.

“Caihong juji: Jurassic Bird-Like Dinosaur Had Iridescent Feathers.” Sci-News.com, 17 Jan 2018.

Dalman, Sebastian G., John-Paul M. Hodnett, Asher J. Lichtig and Spencer G. Lucas (2018). “A New Ceratopsid Dinosaur (Centrosaurinae: Nasutoceratopsini) from the Fort Crittenden Formation, Upper Cretaceous (Campanian) of Arizona.” New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, Vol. 79, 2018, pp. 141–164.

“End-Triassic Volcanism Triggered Dawn of Dinosaurs.” Sci-News.com, 21 Jun 2017.

Gates, Terry A., Khishigjav Tsogtbaatar, Lindsay E. Zanno, Tsogtbaatar Chinzorig, and Mahito Watabe. “A new iguanodontian (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Early Cretaceous of Mongolia.” PeerJ, Vol. 6, 3 Aug 2018.

Geggel, Laura. “'Miracle' Dinosaur Whose Bones Survived Being Blown Up Discovered in Italian Alps.” LiveScience, 19 Dec 2018.

Greshko, Michael. “Bizarre 12-Ton Dinosaur Crouched Like a Cat.” National Geographic, 27 Sept 2018.

Kaplan, Karen. “This dinosaur from Egypt is a really big deal — in more ways than one.” Los Angeles Times, 29 Jan 2018.

de Lazaro, Enrico. “Elephant-Sized Dicynodont from Triassic Period Discovered: Lisowicia bojani.” Sci-News.com, 27 Nov 2018.

de Lazaro, Enrico. “Giant Dinosaurs Appeared at Least 25 Million Years Earlier than Previously Thought.” Sci-News.com, 9 Jul 2018.

McCall, Rosie. “New Species Of Dinosaur Challenges What We Thought We Knew About Titanosaurs.” IFL Science, 7 Dec 2018.

McDonald, Andrew and Douglas G. Wolfe (2018). “A new nodosaurid ankylosaur (Dinosauria: Thyreophora) from the Upper Cretaceous Menefee Formation of New Mexico”. PeerJ, Vol. 6, 3 Aug 2018.

Mueller, Rodrigo T., Max C. Langer, and Sergio Dias-da-Silva. “An exceptionally preserved association of complete dinosaur skeletons reveals the oldest long-necked sauropodomorphs.” Biology Letters, 21 Nov 2018.

“New Carnivorous Dinosaur Unveiled: Tratayenia rosalesi.” Sci-News.com, 16 Apr 2018.

“New Dinosaur Species Discovered in Australia.” Sci-News.com, 16 Jan 2018.

“New Dinosaur Species Discovered in Australia: Weewarrasaurus pobeni.” Sci-News.com, 6 Dec 2018.

“New Species of Titanosaur Unearthed in Egypt: Mansourasaurus shahinae.” Sci-News.com, 30 Jan 2018.

Penkalski, Paul (2018). “Revised systematics of the armoured dinosaur Euoplocephalus and its allies”. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. Vol. 3, Issue 287, pp. 261-306.

Pretto, Flavio A., Max C. Langer, and Cesar L Schultz. “A new dinosaur (Saurischia: Sauropodomorpha) from the Late Triassic of Brazil provides insights on the evolution of sauropodomorph body plan.” Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 25 May 2018.

Rivera-Sylva, Héctor E., Eberhard Frey, Wolfgang Stinnesbeck, Gerardo Carbot-Chanona, Iván E. Sanchez-Uribe, and José Rubén Guzmán-Gutiérrez. “Paleodiversity of Late Cretaceous Ankylosauria from Mexico and their phylogenetic significance.” Swiss Journal of Palaeontology, Mar 2018, Vol. 137, Issue 1, pp. 83-93.

Switek, Brian. “Newly Discovered Tyrant Dinosaur Stalked Ancient New Mexico.” Smithsonian Magazine, 9 Oct 2018.

Switek, Brian. “Paleo Profile: The Jinyun Shield.” Scientific American, 16 Mar 2018.

Switek, Brian. “Paleo Profile: The Mansaoura Lizard.” Scientific American, 2 Feb 2018.

Switek, Brian. “Paleo Profile: The Rainbow Dinosaur.” Scientific American, 19 Jan 2018.

Switek, Brian. “The Latest in Horned Dinosaur Fashion.” Scientific American, 11 Apr 2018.

Switek, Brian. “The Most Massive of Dinos Evolved Earlier Than Previously Thought.” Smithsonian Magazine, 9 Jul 2018.

Tarlach, Gemma. “Ingentia Prima: A Dinosaur Making It Big On Its Own Terms.” Discover Magazine, 9 Jul 2018.

Tarlach, Gemma. “Meet Saltriovenator: Oldest Known Big Predatory Dinosaur.” Discover Magazine, 19 Dec 2018.

Tarlach, Gemma. “Slow (Thunder)Clap for New Giant Dinosaur Ledumahadi.” Discover Magazine, 27 Sep 2018.

Taylor, Mike. "What if Amphicoelias fragillimus was a rebbachisaurid?" Sauropod Vertebra Picture of the Week, 21 Oct 2018.

“Two New Alvarezsaurian Dinosaurs Unearthed in China.” Sci-News.com, 27 Aug 2018.

University of the Witwatersrand. “Ledumahadi mafube—South Africa's new jurassic giant.” Phys.org, 27 Sep 2018.

Zhang, Qian-Nan, Hai-Lu You, Tao Wang, and Sankar Chatterjee. “A new sauropodiform dinosaur with a ‘sauropodan’ skull from the Lower Jurassic Lufeng Formation of Yunnan Province, China.” Scientific Reports, 7 Sep 2018.