Sigmund Freud's The Uncanny and Clive Barker's Hellraiser

Clive Barker’s gothic film Hellraiser presents the audience with many frightening elements typical of the horror genre. The disturbing mutilation of human flesh and supernatural conflict with demonic beings from a veritable hell characterize the film as horrific. Said frightening elements interact with the character Julia Cotton in a manner representative of how the repressed desires of one’s infantile complexes later manifest themselves as something unrecognizable to him or her in the process outlined by Sigmund Freud in The “Uncanny”. Julia must face a secret from her past when it literally returns to her as something grotesque and unrecognizable, setting the stage for a series of events which exemplify Freud’s notion of the uncanny.

It is necessary to first clarify why Clive Barker’s Hellraiser does not evoke an uncanny response from the audience. The film is indeed a frightening display of images and situations, but it works within clearly defined parameters. The audience understands that it is a horror film that is self conscious of the fact that it works to entertain through a series of events that are understood to be impossible in reality. Through the invention of the disfigured Cenobites, his own concept of hell, and a man’s return from this hell, all set in the world we know, Barker has “[chosen] a setting which though less imaginary than the world of fairy tales, does yet differ from the real world by admitting superior spiritual beings such as daemonic spirits or ghosts of the dead” (Freud 950). Said beings have their place and role in the world constructed by Barker, and therefore “lose any uncanniness which they might possess” (950). Considering the film through this understanding, in relation to Freud’s theory of the uncanny in fiction, “we adapt our judgement to the imaginary reality imposed on us by the writer, and regard souls, spirits and ghosts as though their existence had the same validity as our own has in material reality” (951). Therefore, the audience reacts to the film as a work of fiction and is able to view it from a comfortable position of disbelief due to the blatantly impossible supernatural elements therein.

The film may not in itself be uncanny, but the experience of Julia is. Promptly following the scene where Frank is torn apart by the Cenobites and presumably taken to their hell, the audience meets husband and wife Larry and Julia Cotton for the first time. They come to the house where Frank (Larry’s brother) disappeared from, which belonged to his late mother, and explore the interior before mutually agreeing to live there. It is during the moving process that Julia reveals to the audience through reminiscence that she had an explicit sexual affair with Frank soon before her marriage to Larry. Julia must be careful to keep the memory of her affair “concealed and kept out of sight” (933), which is theatrically symbolized in the film when Julia surreptitiously pockets a folded photo of Frank in the presence of her step-daughter, Kirsty, who interrupts her reverie. Once alone, Julia returns to her memories of Frank and the details of their sexual encounter. She is interrupted again, this time by Larry who requires assistance for a minor injury to his hand. It is after they both leave for the hospital that the audience sees what appears to be a decomposed corpse break through the floorboards, in the room where Julia was thinking about Frank, and gradually develop into a partially flesh-covered skeleton, which is later discovered to be Frank himself, who has escaped from the Cenobites and their hell. Freud asserts that this is not true of all fiction, however “death and the re-animation of the dead have been represented as most uncanny themes” (948). I argue that this explicitly literal re-animation of Frank is uncanny because “[it] is that class of frightening which leads back to what is known and long familiar” (930). It is obvious through her vivid memories how well Julia knew Frank and she is the person who has the most interaction with Frank throughout the film upon his return.

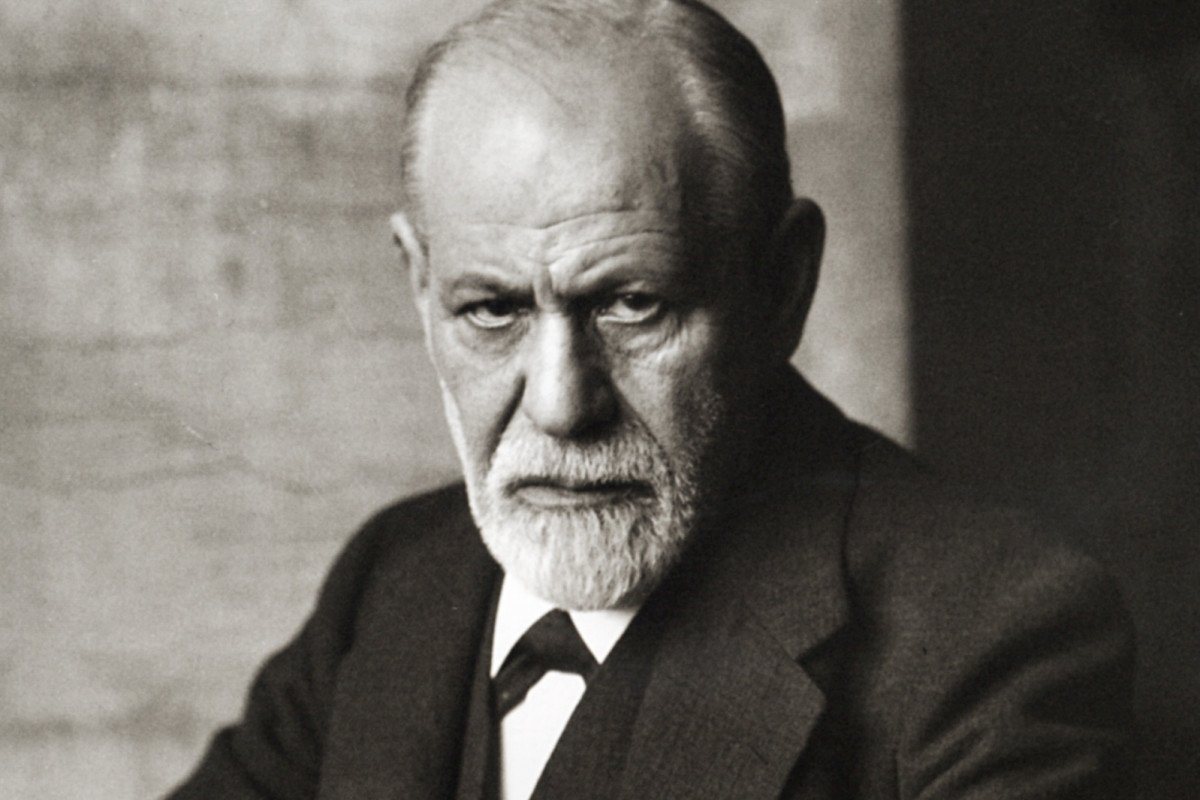

Sigmund Freud (approx. 1920)

It is clear that Julia does not repress her past affair with Frank and her continuing desire for him, in the sense that Freud suggests, but she still has her feelings and past actions regarding Frank return to her as something frightening (944). In Julia’s case, her situation is much more literal than the psychological anxiety Freud asserts is the result of repression. For Julia, her continued desire for Frank is fulfilled as he himself, albeit not as she remembered or desires him, physically returns to her. Julia’s reaction to Frank when she first discovers him is of obvious horror, fear, and revulsion, which intensifies after he tells her who he is. Julia’s situation is a physical representation of the mental process Freud asserts is the result of repression, and is therefore a representation of the uncanny.

Not only does Frank return, he calls on Julia to fulfill a promise she made to him during their affair. Remembering her ambiguous promise to do anything for him, about thirty minutes into the film, is the reason Julia agrees to feed people to Frank in order to fully restore him to his former self. This aspect of Julia’s situation with Frank directly exemplifies part of Freud’s notion of what is uncanny. It is certainly frightening for a woman to lure men into her home under false pretences, and then proceed to kill them, but it is Frank’s ability to draw out the entire life force from the bodies and his ability to finish off the third victim, who Julia failed to kill, that makes her “evil intentions” (945) uncanny: “In addition to this we must feel that [her] intentions to harm … are going to be carried out with the help of special powers” (945). Julia’s capacity for murder is made uncanny by Frank’s supernatural ability to, in a way, consummate her murderous actions.

Julia is distressed and disgusted after her first kill, as is indicated by her reaction to it and desire not to do it again, but she is much more calm the second time she leads a man to Frank and kills him. After this second murder, halfway through the film, there is a scene where Julia is sitting alone looking very pensive, even smiling before the scene cuts back to her and Frank discussing their future plans. Julia has clearly lost her disgust for Frank, as well as her scruples about murder, and is enthusiastic about their plan and her obligation to him. Killing men and having Frank consume their essence also desensitizes Julia to violence that she once found revolting, as she claims: “I’ve seen worse,” after Larry comments: “I thought this kind of stuff made you sick,” while watching a boxing match on television together. Freud comments on the work of Ernst Jentsch who claims that “the better oriented in his [or her] environment someone is, the less readily will he [or she] get the impression of something uncanny in regard to the objects and events in it” (931). Therefore, as she grows accustomed to Frank’s grotesque appearance, and her disturbing task of killing people for him, her sensitivity to the uncanniness of her environment fades as she accepts her own baleful part in the uncanny situation.

The role of Sigmund Freud’s notion of the uncanny in Clive Barker’s Hellraiser is strictly internal. The audience is not susceptible to an uncanny reaction from the film, but the interaction between Julia Cotton, her past, and the uncanny return of her past theatrically represent Freud’s notion of the uncanny as the conscious reaction to repressed desires. In conclusion, the uncanny nature of the film comes not as a reaction from the audience, but as a veritable representation of one’s uncanny reaction to repressed desires.

Works Cited

Freud, Sigmund. “The ‘Uncanny’”. The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Ed.Vincent B. Leitch. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001. 929-52. Print.

Hellraiser. Dir. Clive Barker. Perf. Clare Higgins, Oliver Smith, Sean Chapman. New World Pictures., 1987. AVI.