- HubPages»

- Books, Literature, and Writing»

- Commercial & Creative Writing»

- Creative Writing

Blossoming of Little Minds (6)

And the story continues . . . and concludes

The theme of this concluding chapter of the story "Blossoming of little minds", is special-children, the endeavor to integrate them into mainstream schooling, and the means adopted to teach them otherwise when such attempts fail.

There must be two new nursery rhymes in every new chapter and there are.

If you wish to revisit the first chapter at this point, please click on the following link:

If you wish to have a re-look at the second chapter now, please click on the following link:

If you wish to have a re-look at the third chapter now, please click on the following link:

If you wish to have a re-look at the fourth chapter now, please click on the following link:

If you wish to have a re-look at the fifth chapter now, please click on the following link:

If not, please scroll down to read the sixth chapter titled "Special who?".

A thoughtful bow to the brave-hearts in our midst . . .

Special who?

Balaranya Nursery School's tryst with special children began in the very first year of its inception.

"Our daughter Swati is retarded. Her mental growth is that of a four year old. We only want her to be with other children of her intellectual capacity, and believe that it would make her happy. We have no expectations absolutely about her academic growth, and are reconciled to her being the way she is. Would you please consider letting her be with normal children? You can even use her for small odd jobs and errands," pleaded the mother of a special child.

Being the kind who couldn't refuse a request of this nature, Suhasini had agreed, and asked the parents to bring their daughter the next day morning. She also felt reasonably confident of handling the child, because one of her teachers, who had joined the school not many days ago, had such a child of her own - with a very mild affliction though, and explained to the others about her experience in caring for such children.

The parents had come the next morning, but apparently without the child. Accompanying them, was a woman of about twenty-five, or more.

"Where is your child?" asked Suhasini.

"This is Swati," said the mother, pointing to the other woman, and noticing the subdued surprise in the principal's eyes added, "I suppose I did not mention yesterday that she is twenty-six. We forget that ourselves sometimes."

"Say hello to this Auntie," commanded the mother.

"Hello, Auntie," said the girl, in a voice which was like that of a grown up, while the manner of speech was akin to baby talk.

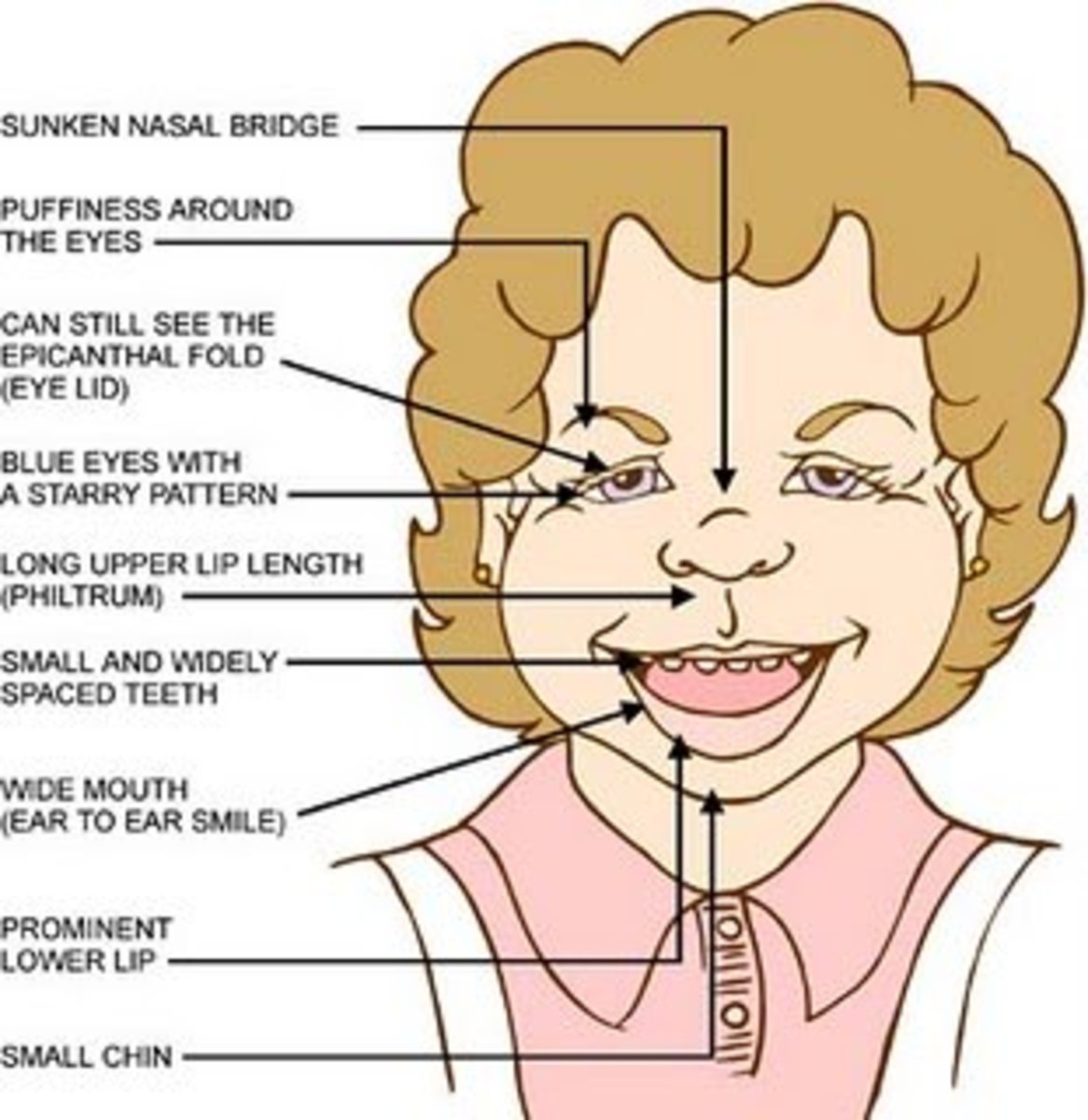

Suhasini watched the woman's face intently. Her small upturned nose and wide mouth, made her look a bit odd, but at first glance; none would have said that she was mentally handicapped.

Indian society, with its emphasis on strong family bonds, had retained the convention of addressing elders as "uncles" and "aunts." In Indian languages, there were specific terms for identifying, maternal, and paternal varieties of aunts and uncles, grandpas and grandmas, grand uncles and grand aunts . . . the list was quite long. With English gradually becoming the preferred language of instruction in most urban schools, the manner of addressing elders - that included female teachers, was simplified to the usage of just two terms - "uncle" and "aunt," but retained its familial flavor. Over the last decade, however, they had begun to make way for the more impersonal and businesslike, "sir," and "ma'am."

The Swati episode dated back to the predominantly "Auntie" era.

Suhasini was at a loss for words, and also found herself in a deep predicament. She had promised the parents that she would admit their "girl," but how would the other teachers react, when they found that the child was a grown up woman of the same age group, as some of them? How would the parents of other children respond?

"Please! Don't disappoint us," pleaded Swati's parents.

Suhasini decided to be open and fair.

"We will take her for a month to begin with. If we find that we are unable to cope - which would primarily be due to our lack of experience in dealing with such children - then I am afraid we will have to discontinue the arrangement," she declared as her eyes involuntarily wandered, and apprehensively looked up the "child" that was being referred to.

"Anything you say," said the relieved father.

"Also, if parents of any of the other children were to complain about her, or this arrangement were to affect the goodwill that the school has in this locality, we will be forced to terminate our understanding immediately."

"She is not the violent type, and will not cause any problem," assured the mother.

Swati was admitted to the UKG class the same day, on a month's probation. The teachers were initially confused about whether to refer to her as "a child," "a girl," or "a woman." Her child-like behavior sorted out the problem by itself. Before the week ended, she was being treated, as any of the other children.

Very friendly, and with a keen sense for music, she would lead the other children in reciting rhymes to tunes. Her fine motor skills, however, were not very developed. She would be of help in the classroom doing odd errands for the teachers. All seemed to go well, until the teachers decided to seek her help to feed the other children.

Swati helped, but helped herself too, when she found anything irresistible in the lunch boxes. A contemptible deed, if attributed to a twenty-six year old woman, but a common trait in a child of four. The children complained to their parents. She was immediately taken off this task, but the damage was done. Some parents, who felt uncomfortable with Swati being with their children from the beginning, but could not muster the courage to say it openly, now saw justification to vent their misgivings.

Suhasini called Swati's parents and terminated the arrangement forthwith. The experience, very limited though it was, of managing a retarded child was to be useful to the teachers in the years to come. It was only a decade later that they got to know that Swati suffered from a condition known as Williams Syndrome, a genetic disorder that causes medical and developmental malady. An upturned nose and wide mouth were distinct facial characteristics of this disorder.

First described in 1961, its estimated rate of incidence was one in twenty thousand births. Life expectancy of individuals afflicted with this disorder was that of a normal person. At that time, the Indian population was seven hundred and fifty millions with a birth rate of about twenty-five per thousand. Suhasini quickly did some mental arithmetic to conclude that there were roughly one thousand children born with Williams Syndrome every year in the country, and even if the population were to stagnate at this level, there would be about fifty thousand individuals alive with such a disorder at any point of time, considering fifty years to be the average life expectancy of such individuals.

These were the figures for just one disorder leading to developmental retardation. There were several others.

It was an appalling thought.

Even during those days, Dayanidhi Ramadas' favorite pastime had been to philosophize. That was the disorder he was born with. Though generally vexatious, he had his sporadic occasions of worth too. Confronted by Suhasini with the depressing statistics on people with developmental disorders, his attempted holistic perspective did provide her with some solace, though she was not entirely convinced with it.

"Disorders have existed all along, even before they were closely analyzed and named. Reckoned as a percentage of population, they would be constant in every age. In ours, they become conspicuous, because of their vast numbers. Their lives and worlds would be the same now as it has always been. This remark is not meant in a deprecating sense, for it applies to the apparently normal beings too," the middle-aged-man of those days had expounded.

"Knowing about them in detail would certainly help in attempting betterment of their lives, wouldn't it?" Suhasini had retorted.

"Take the case of one of your teachers - Harita is her name, is it not? You have extolled her limitless patience, and profound understanding, in dealing with disabled children, and the difference that she has made to their lives. You have also said that she has not acquired this ability, but is just made that way. Am I right?"

"Yes," affirmed Suhasini, receptively.

"If you were to compare her contribution to that of another person who has acquired descriptive details about the disorder, and attempts a symptomatic approach at betterment, you would find that, but for the jargon - which is useful in describing the process to others, Harita's care and tending would be overwhelmingly more effective," Dayanidhi had said.

"Ha! You seem to imply that the study of such disorders, and their dissemination, is nothing more than a glamorous activity with no practical utility," Suhasini had protested.

"No, I didn't say so. Study and dissemination certainly has its uses - more than one use in fact. Firstly, it tells us more about the processes of life. Secondly, it creates awareness in people about the plight of those who are not as privileged as they themselves are. Thirdly, it makes us look at possibilities of intervening during the pre-natal phase to avoid such births, depending upon the ethical implications of such attempts," Dayanidhi had explained.

"Don't you see any other differences in approach to the care for the disabled between earlier times and now?" Suhasini had persisted.

"Yes, I do. As I see it, the proportion of ambition and high expectation in the motivational characteristics of today's society is substantially more compared to earlier times. It was acceptance and contentment that was more pronounced in the past. I have no experience of having lived then, but this is my surmise of human history. Each paradigm sets its own priorities. Society expects a particular kind of result from the approach that it adopts, dictated by such priorities. But these do not directly concern those that are afflicted with the disorders, nor those who care for the afflicted," the part-time philosopher had concluded.

But for minor perceptive differences, this deduction had appeared to be fairly satisfactory, and soothed her disturbed mind. It had also provided the clarity of thought to take a decision, to confidently admit and care for children with disorders at Balaranya Nursery School.

One of the first such admissions was a girl named Vedika. In addition to being one affected by Cerebral palsy that had resulted in her inability to control muscle coordination, and in her mental retardation, she was also blind. There wasn't much that they could do for the child, her only unimpaired faculty for communicating with the world being her sense of hearing.

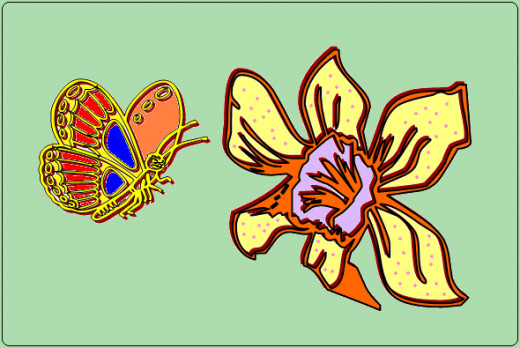

Whenever she was in the midst of children reciting or singing rhymes, there would be a marked glow on her face, and a smile on her lips, that indicated her delight. One could only speculate whether she understood anything about what was being said. Perhaps, she had her own special means of comprehension. She was particularly ecstatic, whenever the rhyme of a flower in the garden was sung.

In a garden green,

A flower was abloom.

Her petals made for her,

A pretty costume.

A beautiful butterfly,

She took for her groom.

All around the flower,

He was seen to zoom.

The butterfly had wings

With many red dots.

The flower's petals too

Had a lot of pink spots.

When they were together,

It was tricky for the eye,

To tell apart the flower

From the butterfly.

In the brightness of the morning,

The butterfly would soar.

He would reach for the clouds,

Until he could fly no more;

From the heights of the blue sky,

Down he would glide.

And alight upon a little leaf,

By the flower's side.

The ants were so thrilled,

The trees were overjoyed.

Even the bees, though disturbed,

Weren't truly annoyed.

The wedding of the couple,

They all came to see.

The flower and the butterfly,

Lived long happily!

It was such a touching sight to witness the spark of joy in the child's face. It gave a new unexplainable meaning to life.

Vedika was with Balaranya Nursery School for about a year. The family moved out of the city, and the teachers never got to see, or get any news about her, after that. But her happy face would always be etched in their memory.

Before the girl had been admitted, Suhasini would often wonder, what had - in the context of cause and effect - retarded children to offer to the world. She had the answer restated every day that Vedika attended the school.

In later years there had been between three to five new admissions of special children every year - a majority of them being either those with Down syndrome, or those who were autistic.

Suhasini had read that Down syndrome was one of the most common disabilities-causing genetic disorders, with an estimated incidence of one in thousand births, which was about twenty times more than that of Williams Syndrome. A quick calculation gave her a staggering figure of one million individuals with this malady in India alone.

Though mental retardation could be severe in certain cases, it was seen to be typically mild or moderate. This enabled Down syndrome children, to more easily integrate with the normal children.

Autism, the teachers learnt, was a disorder that was even more common than Down syndrome, its prevalence being one in five hundred children, with a particular predisposition towards male children. It was not a genetic disorder, but caused due to structural abnormalities in the brain. There was also no medical test for diagnosing autism. But like Down syndrome, Williams syndrome, or Cerebral palsy, there was no cure for this condition. Children learnt to cope with it, and get on with life, as best as they could. Teachers, who made an effort to understand them, helped them in their endeavor.

A small and innocuous advertisement, hidden in one of the middle pages of a Sunday newspaper caught Suhasini's attention. For her, reading the edition from end to end was one of the main occupations reserved for that glorious day of the week, when the whole world was supposed to relax.

The advertisement was about a workshop to be held by two renowned special children educators in the country, who were known for their simplicity of approach and dedication to the cause. The theme of the workshop was mentioned as, "Teaching strategies for differently-abled children," with particular emphasis on those showing symptoms of dyslexia, Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD), and Down syndrome'. A telephone number was mentioned for making reservations.

Suhasini immediately picked up her cell phone and made reservation for all her teachers and herself for the course that was scheduled for the following Sunday. She would send the course fee across the next day with Abida.

The week sped by, and the Balaranya Nursery School staff found themselves seated in the small auditorium of a high school, that had graciously agreed to the request of the special children educators to let them use the school's premises for their training course.

An attendant had placed a plastic folder with a notepad, a ballpoint pen, and a bottle of mineral water on each desk, as soon as the participants had trooped in and taken their seats. A man of about fifty and a woman, who might have been a little older, made their appearance immediately afterwards, sporting welcoming smiles that they genuinely meant, and walked up the two steps to the dais.

"Welcome! All of you," began the woman, "I am Meherunissa Ali, and this is Hari Prasad Sharma. We will be your hosts for the workshop on "Teaching strategies for differently-abled children." Let us begin by sharing our ideas about what we think ability is, and what is it that we find different in the abilities of those whom we categorize, as "differently-abled." Does any one of you wish to voice your opinion?"

A diffidence-induced silence pervaded the room. Some looked out of the window, some scanned the ceiling, and others surveyed their feet, while the more courageous stared at the couple on the dais unblinkingly.

"Relax, folks. This isn't a lecture. It is a workshop, and we are among friends. So feel free to voice your opinion. It is only by sharing our thoughts that we all learn," coaxed Sharma, in his inimitably disarming style.

His charm seemed to be warm enough to immediately thaw the stillness from the gathering. One woman put up her hand to draw attention, and said, "Ability, I would say in this context, is the capacity to interact with society on one hand, and the environment on the other, to promote one's interest. Extending this idea further, I would categorize those who lack this capacity as disabled, though it is fashionable these days to use the term differently-abled."

"Thank you, my friend. Could you please introduce yourself?" said Sharma.

"I am Amala Goswami, and I work as an instructor for special children at the Gandhi Memorial School," the woman responded.

"Thank you, Amala. Meher and I agree with your observation on the definition of the word 'ability,' in the context of this workshop. But we also feel that we need to go deeper, and further elaborate, on the phrase 'promote one's interest.' Do you agree Meher?" Sharma passed the mantle, to his colleague beside him on the dais.

Over the last year, from the time they had begun conducting such workshops regularly, the two of them had become adept at making the sessions very interactive and interesting, seamlessly shifting the responsibility of conducting the workshop between them for short spans.

"Yes, Hari. But let us hear what the others in the gathering have to say. How about the gentleman over there, in the last row?" said Meher, gesturing to one of three men in the room.

"I agree with what Amala mentioned, except for the fact that I believe disabled children lack the understanding about what is in their interest. It is like going around in circles. They do not have the capacity to interact with their environment and society, as normal children do, and they do not seem to know what is good for them. The role of an educator in such circumstances can be quite frustrating, given the expectation of parents," said the man, and then added, "I am Martand Waghle, from Jupiter High School."

The room suddenly seemed to have come alive. All it needed was one participant to be persuaded to speak his or her mind, and the rest unconsciously felt emboldened to voice theirs. There were five raised hands now, awaiting their turns to speak.

Some opinions were variations of the perspective of the first two; others further broadened the focus of enquiry. Very soon, a point was reached, which if allowed to persist, would have led to utter chaos. The two coordinators watched the action from the elevation of the dais, and when they felt that the participants had been made to shed their inhibitions in sufficient measure - "to loosen 'em up," was the term that they used in private for this state of affairs, Sharma held up his hands to arrest the tempo of exchange, and said, "All right friends. Now, that we have your different impressions on the matter, let us take the next logical step of consolidating all of them, and see whether a consensus can be arrived at. We will identify the areas, where the ideas converge, and those, where they sharply deviate. Meher will be our analyst."

"Well," began Meher, "all of us are agreed on the point that special children - I will not say lack the ability, but would rather declare that they are slower than an average person in their interaction with the environment. We cannot create a new ability in a person. We can only attempt to enhance what already exists, and hasn't been able to attain its potential. This slight shift in our perception has the double effect of elevating a special child to a pedestal of hope, and our approach to teaching and helping such children, to a platform of optimism."

She paused for a few moments, for her words to sink in. Sharma intently watched the faces of those seated in the room, for any expression of dissent; most seemed in thoughtful agreement. Only one demurred.

"Do we have a consensus on this here?" asked Sharma, directing his gaze on the source of possible discord.

"Are we not just painting something that is inherently dark to give it a façade of gaiety?" asked Martand Waghle.

"Isn't that what we all do, every day of our lives, Martand?" retorted Sharma, in a voice that was at the same time friendly and reproving. "Why are high-healed footwear sold by the millions each day? Why are swanky limousines bought on borrowed money? Why do people insist on being addressed by the titles conferred upon them, or revel in appending their educational qualifications behind their names? Why do many of us get our clothing designed in the same fashion, as those worn by people who take our fancy? Are we not trying to be what we are not? Are we not painting our inherent self to create a façade of what we would like to be, but which we can never be?"

The words had been spoken very softly, but seemed to have the power and intensity of a sledgehammer. It assured the two coordinators the full and purposeful attention of their class for the remainder of the workshop that was to stretch across the next three hours.

"If we are agreed on the first premise, shall we proceed to the next point?" asked Meher, breaking the pervading silence.

Thirty-eight heads nodded in unison.

"We had a disagreement about what constituted 'promoting one's interest.' Hari's eloquence a few moments ago provides a perfect backdrop to analyze this question. What constitutes an individual's interest?" asked Meher, directing the question at all those present with a gaze that panned the room.

A response took a relatively long time in coming, as everyone was on guard about what each said, after the stinging rebuttal a while ago. Martand Waghle would not have dared opening his mouth again that day.

"I suppose it is what we perceive to be satisfactory to us. I use the word 'perceive,' because it need not be necessarily satisfactory in actuality."

It was Amala Goswami again, trying to be cautious, and providing ample flexibility to wriggle out, if the situation got knotty.

"Exactly, Amala. You don't need to be tentative," said Meher, and turning to Sharma passed a mock stricture on him "Hari! Don't you see that you have scared them all into muteness?"

Sharma prolonged the charade for a few instants more, by putting his hands up, and bowing down in mock submission. The tension of the last few minutes melted away, with smiles blossoming on every countenance.

"We also need not be apologetic about our seeming self-centeredness in pursuing what appears satisfactory to us." continued Meher, "But the point is, we forget the fact that the disabled too have their own point of view about what is satisfactory to them. We are being unfair, when we project our notion of satisfaction upon others, particularly the disabled, who do not have the wherewithal - as normal people do and also make use of with vehemence, to counter such an infringement upon their rightful independence. Are we in accord on this point as well?"

"Do not be scared of Hari Prasad Sharma. I will handle him," she added, as a precautionary jest, which had its desired effect on the audience as a whole, and Martand Waghle in particular.

"Let me express a genuine misgiving, and I am ready to be corrected by Hari," said Waghle, chuckling. "We only mean well, when we suggest and perhaps, impose our views upon those whom we love, or upon those who are under our care. Surely, there is something like a common good, is it not?"

"I apologize, if I sounded harsh, but that certainly was not my intention. Certain ideas need to be put forward with the right amount of intensity for it to be meaningful. It was just one of those situations earlier, that made me say what I said the way I did," replied Sharma, looking at the audience in general.

Then turning to Waghle, he said, "Yes, there is indeed a common good, when all those who represent the 'common', think about, aspire for, and pursue, some ideal alike. With a normal person, we can ascertain this similarity of purpose. With disabled persons, and particularly with disabled children, we do not bother to find out, and even if we tried, we cannot fully comprehend their desire. That is our disability."

"Bravo!" said Waghle, with a spontaneity that reflected his real appreciation.

It was not without reason that the duo had become renowned for their work in the field of care for disabled children. This had come without any manner of intentional advertisement. All those attending the training sessions and workshops conducted by them for special instructors, went back completely satisfied, convinced, and enthused about their profession, which was the best form of advertisement that any one could hope for.

"I feel that we have laid the strongest possible foundation for the edifice that we are going to build over the next three hours," said Meher. "We understand each other perfectly, and are friends. We have established and are convinced about the two basic principles that are going to guide us in whatever that we do from now on. Let me write these two principles on the board, so that they become etched in our minds, never to be erased."

So saying, she took a felt pen from its stand near the light bluish-grey colored board on the wall behind the dais, and wrote upon it in bold letters, repeating what she wrote aloud - word by word.

"Disabled children do not lack the ability to interact with their environment; they are only slower than an average person in doing so."

"We do things that promote our interests. Our interests are ideas that appear satisfactory to us. We are being unfair, when we project our notion of satisfaction upon others, particularly the disabled."

The open page of thirty-eight writing pads mirrored the board in generality. There were inescapable variations though - some inscribed along the length of the pad, while some did along its width. Some used cursive writing, a few used blocks. They slanted left, slanted right, or did not slant at all; diminutive, relatively normal or oversized letters; legible to the world at large, or illegible even to the one who wrote it. In effect, there were thirty-eight unique reflections of a single effect - the very taste of life.

"We will now discuss another point," said Meher, replacing the fat felt pen in its stand. "It could be construed to be a corollary to point number two on the board, or considered as an independent axiom."

"What do we do, when we are confronted with a problem - it could be the simplest of things, such as carrying a cup to the lips to sip a hot beverage, or a complex, life threatening situation like being assaulted by a terrorist?" she asked, with an enquiring look on the attentive faces.

"Shanta," Meher's wandering eyes rested on one of the woman participants, who had introduced herself earlier during the discussion, "What would you do in the latter scenario?"

"Close my eyes, and pray to God, perhaps," replied the woman.

"And you Swastik, you look very athletic, and if I remember correctly, your resume mentions that you are also a judo instructor, what would you do in a situation such as that?" questioned Meher, turning to the man sitting near the door.

The man colored a little, before saying, "I may try to overwhelm him, if that was possible."

"Good. We have two different reactions to a given problem. If every one of you were to answer this question, I am sure there would be as many different responses, which maybe categorized into three or four distinct types, but certainly unique in themselves," continued Meher. "We use logic to analyze a problem confronting us on the basis of our past experiences and our inherent qualities to arrive at a solution appropriate for us. The logical process is standard, but the inputs to it, and correspondingly the output that it generates vary with individuals. Let us, for the sake of simplicity, call the whole process - including the unique set of inputs and output - as the individual's logic. So, each person has his or her own logic."

"Now apply this reasoning to a disabled child. It will have its own logic too, limited by its short experience, and restricted intrinsic qualities. If we have to help a disabled child, we need to understand its logic. Only then, can we hope to make some headway. Does the argument sound convincing?" enquired Meher.

"I am Suhasini Ranganathan from Balaranya Nursery School," said Suhasini, who was taking part actively in the discussion for the first time. "Don't we try to mould our children - even the normal ones - according to the beliefs that we hold dear? We don't attempt to identify their logic in this process, do we?"

Meher glanced at Sharma, and caught his eye, her look silently communicating, that he had better take over.

"Agreed, Suhasini. Parents do want to mold their children according to what they feel is the right way to live. I had been to a junior college in New Delhi. Students are segregated into four sections. The elite section has all the toppers from the tenth standard who are entirely focused on what they wish to achieve, whether or not their parents support their choice. The remaining sections are mostly filled with students who are quite disinterested in what they have been forced to pursue by their parents. They spend more time outside the college than inside. If that is called molding, then I disagree. If all parents attempt to understand the logic of their children, and help them in achieving what they enjoy doing, the world would be a happier place." Sharma's voice had adopted his characteristic tone - friendly, yet stern. "When dealing with disabled children, as their teachers, we are obliged to follow axiom two that we have agreed by consensus to be correct and appropriate, as we are being paid for it."

Suhasini did comprehend Sharma's bent of thought, but she was not entirely convinced.

Sharma sensed her uncertainty, and said, "I know that we are walking on thin ice here. Perhaps, there will be more clarity, if we consider an adult-adult interaction. Let us look at a hypothetical situation, where both Shanta and Swastik are confronted by a terrorist. One prays to God for a miracle, while the other prepares to tackle the offender. Maybe Shanta, even upon knowing that Swastik can save her, would rather prefer a miracle from God - such as lightning from the sky, or the parting of the earth - to neutralize the terrorist, than being indebted to Swastik."

There were smiles all around, and Swastik blushed some more.

"All that Meher and I wish to emphasize, is that we treat a child - normal or disabled, as an equal which has its own logic, its own way of looking at the world, its own inherent and unchangeable qualities, which are as important and vital to it, as our own are to ourselves."

The crease of uncertainty appeared to have greatly diminished on Shanta's brow.

Discussions continued for a while longer, following the regular pattern of Meher analyzing an idea, participants articulating their opinion about it, and Sharma, summing it up.

And then it was lunchtime.

"That concludes the morning session folks," announced Sharma. "Let us all fortify ourselves for the session to follow in the afternoon. The school has arranged some excellent lunch for you. Our assistant Ghanshyam will show you the way."

As the gathering crowded around the door on its way out, Swastik turned to Sharma, and asked, "You have an excellent insight about the way minds of disabled individuals work. How long have you been involved in working with them?"

"All my life; I am a dyslexic," said Sharma with an expressionless face. Many heads turned towards him in bewilderment.

"And if I am what you have assumed me to be," he said after a pause, "then I owe it to those who followed the axioms that we have discussed so far, to help me in my formative years."

The afternoon session of the workshop was an equally interesting, and interactive affair. The two educationists shared their experiences, and also confided that, though they had opted to teach in a school for special children under the conviction that their skills would be better utilized in such an environment, they also shared the opinion that it was wrong to segregate children thus. They felt that every child - normal or special - had some disability or the other. Those with exceptional intelligence were extremely few, and even they would surely have some disability. They believed that to a large extent, our definition of cleverness and stupidity was influenced by our focus on what we considered to be the aim of life.

If at all there is a need for segregation, it should be such outstanding children, who should be provided a different environment that is commensurate with their extraordinary abilities in specific domains. That would be a much better and purposeful utilization, of teaching skills. Instructors too could experience a greater fulfillment in such an environment.

All other children should be classified not by age, as is generally being done, but by their capacity to understand and absorb knowledge, and taught using techniques that were now, exclusively meant for supposedly abnormal children. This would, in their view, substantially bring down the dropout rate, make children enjoy what they learn, and become better citizens and human beings.

Views were changing slowly among educationists at the helm of affairs. But change required time. A change suddenly wrought, and forcibly imposed would lead to other complications. People like Meher and Sharma could only hope that someday, such a complete change would indeed come. Until then, they would have to be content with contributing their own little individual assistance towards furthering the cause.

The special educators also mentioned the effectiveness of "Animal Assisted Therapy," that made Suhasini recollect the visit of the Zoo-man some months ago.

"How many of you have had pets?" asked Sharma.

There were only five hands raised.

Sharma made a face expressing his utter disappointment at this.

"Those of you who have not had this experience have missed something in life. At least all educators of special children should make it a point to have a pet. You will be able to understand the needs of the special children much better by doing so, because their ability to interact with animals can have a very positive impact upon their quality of life. It can change behavior, and create a sense of responsibility. Special children are often extremely trusting, and easily achieve a level of intimacy with animals, which normal children, as well as adults cannot," said Sharma.

"The special bond that is formed, contributes to the pets' effectiveness as co-therapists. It is, as though the animals are able to sense the relative helplessness of the children, and volunteer to help."

It was a thoroughly satisfied set of participants, who returned to their respective homes from the workshop that evening. A new spark had been lit in each of them; a new conviction had taken root in their hearts.

As a parting gift, the special educator duo had presented every participant with a folder that contained a copy of a book that they had authored recording several case studies, and a booklet that listed all known disorders that led to mental developmental problems, with a brief on each of them. It also had a little book of rhymes with five poems for children that the duo had composed. The teachers of Balaranya Nursery School found one of them particularly appealing, and it was soon appropriated into the school's already large ensemble.

I like an apple,

The green one more than red.

Mamma lets me have one,

Before I go to bed.

She says it will make me

Very healthy and strong.

And I'll never need

A needle poke, life long.

I like an orange,

'Cause its called and colored so.

With many sections stacked inside,

Neatly in a row.

Mamma peels the skin first,

Then sets the slices apart.

She puts them into a pastry shell

And serves it, as tart.

I like Jackfruit,

But not its pungent smell.

Tis fun to watch mamma remove,

The segments from the shell.

She washes them and then extracts

The seeds from the meat,

And serves the flesh with honey.

Oh, aren't they yummy to eat!

I like grapes,

Those bunch of little balls.

You pluck one from the bunch

And another by itself falls.

Papa likes its juice

Fermented into wine.

And sips it from a crystal glass

In the evening, when we dine.

I like mango,

Very yellow and ripe.

With a few red spots

And many a green stripe.

Green for sourness,

Yellow for sweetness chaste.

Red to show that together

They give a tangy taste.