A Forkful of Peas and a Pickle Dish

Whether at the White House, the Elysée Palace or Windsor Castle, preparations for a state banquet will begin many months in advance. The guest list and placement, the menu and the wine, of course, but considerable thought is also invested in the table setting to present a dazzling and, on occasion an intentionally intimidating, display as assembled guests process into the banqueting room.

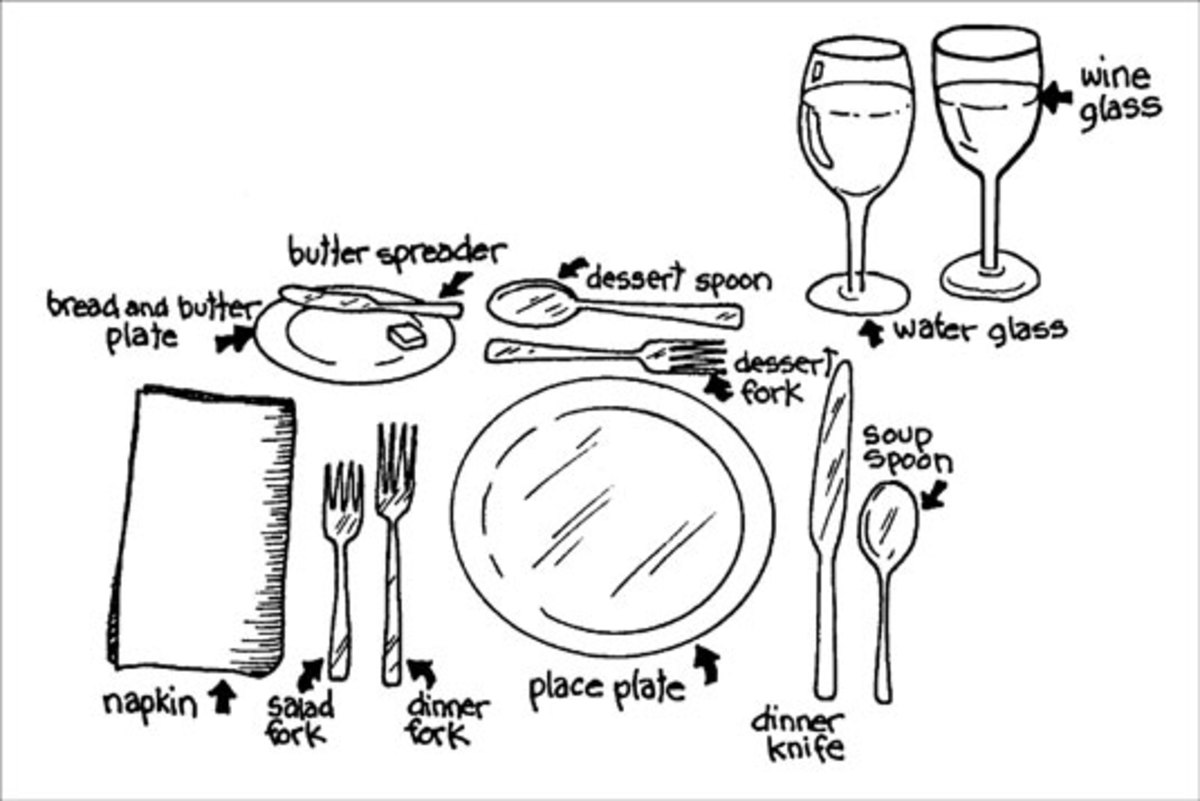

From the grandest occasion with a hundred dignitaries seated at a long u- or horse-shoe shaped table, to a less formal affair of multiple tables of eight or ten guests, attention to detail will be painstaking and setting the tables will begin several days in advance. Each guest will be seated before a placement which may include up to six glasses, damask linens, gilded chargers, magnificent silverware and a daunting array of cutlery. Depending on the menu, there may be three of four forks and even more knives, as well as silver gilt knife, fork and spoon for the fruit course.

Such splendor is in marked contrast to the medieval period when, other than the spoon, a familiar implement throughout Europe from the days of the Roman Empire, food was eaten with the fingers. By the Middle Ages, a small refinement among upper classes insisted that only the first three fingers be used, and to use all five was considered vulgar. Other times, different etiquette - it was considered bad manners to wipe one's fingers on anything other than the table cloth and in his book, De Civilitate Morum Puerilium (On good manners for boys), Erasmus advised that good manners dictated a spoon be wiped before passing it to one's neighbor! On the niceties of such small considerations do societies learn to rub along together.

At the time his book was published in 1530, the medieval banqueting style was an extravagant display in which huge quantities of dishes were placed on the tables, sweet and savory, all served together in a gargantuan excess. The knife that the male diner used at table was the same blade carried with him at all times, whether a dagger or stiletto or other small weapon of choice. It was good manners for the man to select and cut choice morsels and serve them by knife tip to the lady seated next to him, since she would bring no knife of her own to table.

Small forks for dining had first appeared in Italy in the eleventh century, brought by the Greek bride of the doge, scandalizing Venetian society which considered the practice an unnecessary affectation, and the poor bride's early demise was judged to be no more than divine retribution. The fork, like the bride, disappeared from mention and memory, until it slowly began to gain some acceptance, and by the sixteenth century it had become widely adopted as an essential and practical dining tool.

The French had shared the Italian's initial scorn for such a needless implement until Catherine de Medici, betrothed to the future king Henry 11, brought her Italian forks with her on her arrival at the French court in 1533. Hardly an instant success, the fork may have been regarded more as a curiosity that nevertheless began to gain acceptance throughout the century.

The initial reluctance to embrace the new implement might more easily be explained if one recalls that the design of these forks derived from the two pronged shape of the larger kitchen forks, carving aids used by the ancient Greeks and the Romans. Ideal for securing meat while it is sliced and speared on the tips for serving, a smaller version but in the same basic design is less well suited for the more delicate negotiation of transferring food between plate and mouth. Nevertheless, the fork gradually and irreversibly gained ground to become standard at court and on the dining tables of the wealthy by 1600. Thomas Coryat, an Englishman setting out in 1608 upon the equivalent of the first Grand Tour through Europe, (a practice which was to become standard part of a gentleman's education in the C18th), introduced the first forks to England on his return C1610-11, after seeing them in Italy. By 1630, the first fork had reached America, where for some time Governor Winthrop owned the only example.

The elementary design of the fork was adequate for its purpose - to pin-down and convey slices or large chunks of food from communal dish to individual trencher, in a diet high in meats. Vegetables were considered to be indigestible comestibles, suited only for the poorer household and the peasantry, a Middle Ages disdain which survived well into the sixteenth century. Contemporary accounts on early seventeenth century European table customs noted that while the French and Germans ate their soup with a spoon, the Italians used a fork. This appears a curious observation but presumably pieces of meat would be speared on the fork and the remaining liquid then drunk straight from the bowl, following the old medieval habit.

This aversion to vegetables had changed by the second half of the seventeenth century, evidenced in reign of Louis XIV. The king took an avid interest in his royal vegetable gardens, and under his royal lead, the court became obsessed with garden peas. Such was the mania that developed, that it became fashion in Paris for aristocracy to indulge in 'snacks' of after dinner green peas, often to excess with the inevitable consequences, not least severe attacks of indigestion. Even the king himself was not immune from the results of over indulgence in peas, having to summon the royal doctors to administer emergency relief. What is almost certain, is that these late night gustatory pleasures were consumed, if not with fingers, then surely by spoon for gluttony would seem to rule out any pretensions to manners, the addicted surely too impatient to first chase and then spear each little green pellet upon prong tip, if the prize was not to be lost in the gaping abyss between the two tines.

The reign of Louis X1V thus saw the coincidental arrival at the French court of two new introductions to the dining table, a topic du jour among the Sun King's courtiers: green peas and the first four-prong fork. A devilish combination still with the potential to bring anguish for many a diner at a formal, grand occasion today. It would be pleasing, and perhaps not too fanciful, to attribute a causal link between the slowly increasing subtleties of the dining room, the arrival among those dishes of garden peas and the further innovation to the design of the fork: a cause and effect between peas and prongs. What is certain is that at sometime during the height of the green pea mania, in the latter end of the seventeenth century, the first four prong fork appeared in France - an enhancement in function and design which did away with much of the need to switch between fork and spoon, the curved tines forming a bowl shape making it easier to scoop up food which then stayed on the fork during the passage from plate to mouth. Three and four prong forks had appeared in Germany by the 1800s and from there into the rest of Europe, England and eventually to America.

In the C16th and C17th, travelers and guests had been expected to include their own cutlery as part of their luggage. This had a practical purpose during the journey itself, since knives and spoons provided by inns, where weary coach and chaise passengers might be obliged to break their journeys, were often filthy. The wise, wealthy or experienced voyager would be sure to carry his own implements. The C18th saw the first concept of the dinner party, in a form we might recognize it today and these lavish affairs, elaborate meals with their extensive variety of dishes, required suitably extensive dinner services and dining rooms. It was no longer practical for guests to bring their individual cutlery and now this too was expected to be provided in matching sets by the host.

The early French manufacturies at Chantilly and St Cloud produced the first European porcelain cutlery handles, initially following the style and decoration of the imported Chinese porcelains. By 1750s, soft paste porcelain handles were also being produced at the Bow and Chelsea works in London, in blanc de chine styles with raised prunus blossoms, in blue and white and polychrome decoration.

The early C18th pistol grip handle shape, or hafts, changed towards the end of the century with flattening and straightening to the hafts, but the pistol grip, a comfortable and natural fit in the hand, would reappear periodically and become once again the favoured handle shape for a time in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century.

In the series of three bankruptcy sales of 1764 of 'John Crowther, of Cornhill, the final sale in May that year records among the 'finest porcelain' were to be sold quantities of decorative figures, candlesticks, dessert wares were ' a quantity of knife and fork handles, some neatly mounted.'

The banqueting style at the C17th French court had been refined and, to some extent, simplified as the vast number and variety of dishes were pared down, but its roots still lay in the excess of the medieval feast, with guests expected to serve themselves buffet style from the array of different dishes all presented at the same time. Dining à la française became the accepted norm across most of the C18th royal European courts and aristocratic households, and had been adopted by all upper and middle class dining rooms by the start of the 1800s. Where France led, fashionable Georgian England must follow and the French chef producing French cuisine, served in the French style became the social requisite. Service was punctuated by several course but within each course, twenty or thirty different dishes continued to be placed altogether on the table, within a certain set of rules which dictated that the display should be artistically arranged and symmetrical but without repetition - each end of the table may be set with a pie but no two pies may be the same. After service of the fish and soup course, with maybe twenty or more different dishes, the meat courses were brought in. These might include a variety of roasts meats, sweetbreads, kidneys, cutlets, stews and even curries. The table would then be cleared - the first 'remove' - and an array of sweet and savoury dishes appeared, jellies and creams among vegetables and game. At the most formal meals, a second and third remove might follow, with fresh fruits and nuts in a dessert course and further dishes such as spicy devilled anchovies for those gentlemen still of peckish disposition. In theory, diners might ask for an out of reach dish to be passed nearer but it is probable that in many instances enjoying a dish of choice might have been impractical. One can only pity the lady guest unfortunate enough to be seated before a steaming platter of tripe a la lyonnaise, when heart and female stomach might be more favorably inclined towards the more delicate dish of roasted song bird placed, out of reach, before the host.

With the development of the French cuisine came an expansion in the use and variety of sauces for each dish, in many instances a necessary accompaniment for foods, especially the meat which formed the main part of the meal. A robustly flavored sauce helped to mask any unpleasant aspects to fare which frequently could be past optimum condition. Francois Pierre de la Varenne, chef at the French court, wrote the first cookery book to record the significant advances in cuisine. Published in France in 1651, La Varenne recorded for the first time the use of a roux, flour and fat, to thicken a sauce. On its subsequent publication in England in 1660, the book was an instant success and sauces became an essential addition to every aristocratic table, at a time when fashion dictated that menu and service must only be French. The upper class households employed French chefs although the middle and working classes continued to favor the traditional English fare and regarded with some distaste the pretensions of those socially superior, a disdain exemplified by the comments of the C18th author Hannah Glasse who, in her cookery book 'The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy' published in 1747, wrote bitingly of the contrast between the French and domestic kitchen, that she had heard of one French cook that used six pounds of butter to cook twelve eggs when anybody knew, that understood cooking 'that half a pound is enough.' She added, 'but then it would not be French.' Seen from modern perspective, everything is relative.

By the eighteenth century, cutlery and flatware, porcelain sauce boats and pickle dishes were required accoutrements. Although service à la française allowed for some tolerance in the placement, haphazard arrangement and application were not uncommon even at the grandest or most fashionable tables. The change to a new style service of banqueting service in the nineteenth century, when fashionable society was introduced to service à la russe. A sequence of dishes would now be served in place of the simultaneous display, bringing with it a more stately and ordered demonstration of opulent dining in which the formal table setting now played an important part.

Each dish in each course now made its own entry in service, new cutlery and flatware was designed for the different courses, introducing the fish forks (fashionable dining now considers these to be bad form but no doubt this will change again in the next generation), salad and oyster forks, pickle forks, pastry forks, fruit knives and forks. Food was now served to each individual guest and if condiments or tracklements were to be served as an accompaniment in a course, each guest had his own portion in a separate, especially designed dish. Although porcelain sauce boats had largely ceased to be produced by the time service à la russe had become established, small porcelain, or more commonly pearlware and creamware, pickle dishes were a standard part of any service. These charming little pieces are highly collectible, prized for their variety of shapes and decoration, and the ease with which they can be accommodated, even in collections where space is restricted. Perhaps of even more merit is their affordability in comparison to the often painfully high prices, asked and realized, for C18th and early C19th porcelain handled knives and forks.

Useful links

- Green peas nutrition facts and health benefits

Sweet, succulent green peas or garden peas are indeed packed with several vital nutrients, plant-sterols, vitamin C, vitamin A and essential minerals such as iron, zinc. - Kitchen Garden of King Louis XIV

The Potager du Roi near the Palace of Versailles, produced fresh vegetables and fruits for the table of the court of Louis XIV. - Cutlery MEDIEVAL DESIGN

Medievaldesign offers a large selection of 12th -15th century clothing, furniture and many other historical products. - Brass, pewter & cutlery in the collections - Victoria and Albert Museum

Objects from the V&A's brass, pewter and cultery collections: Presentoir, Carving Knife and Fork Handles of ivory and piqué work, silver, red and green painted enamel, steel blades, etched and part gilded Germany, dated 1682.Inscribed German &