Food Health Claims: Fact or Fiction?

Extraordinary Claims Require Extraordinary Evidence

Or rather, they require scientific evidence as set out in Article 13 of the EU Regulation on nutrition and health claims made on foods (1924/2006) as amended by EU Regulation 1047/2012. Please click on the links in the previous sentence if you want to know more about the intricacies of food labelling rules in the EU - but if you'd rather skip that, it basically means that all health and nutrition claims made by a manufacturer or vendor must be clear, accurate and based on scientific evidence. Any claims must be true and not misleading, and easily understood by the consumer.

It is also forbidden to claim or imply that food can treat, prevent or cure any disease or medical condition.

These rules exist to protect consumers and ensure consistent quality in production. The legislation means that there are some things that you just can't say on packaging or in marketing material, even with the best of intentions. But we've all heard anecdotes about so-called superfoods, or the latest celebrity health fad. Most of these claims have a very shaky foundation, if they have one at all, but there are a few that stand up to scrutiny. Prepare yourself for a Feast of Facts. And keep your elbows off the table!

Proceed With Caution

There is no food that will cure any illness. If you're sick, see a doctor. Any benefits listed in this article are largely preventative, and marginal in comparison to simply eating a healthy, balanced diet.

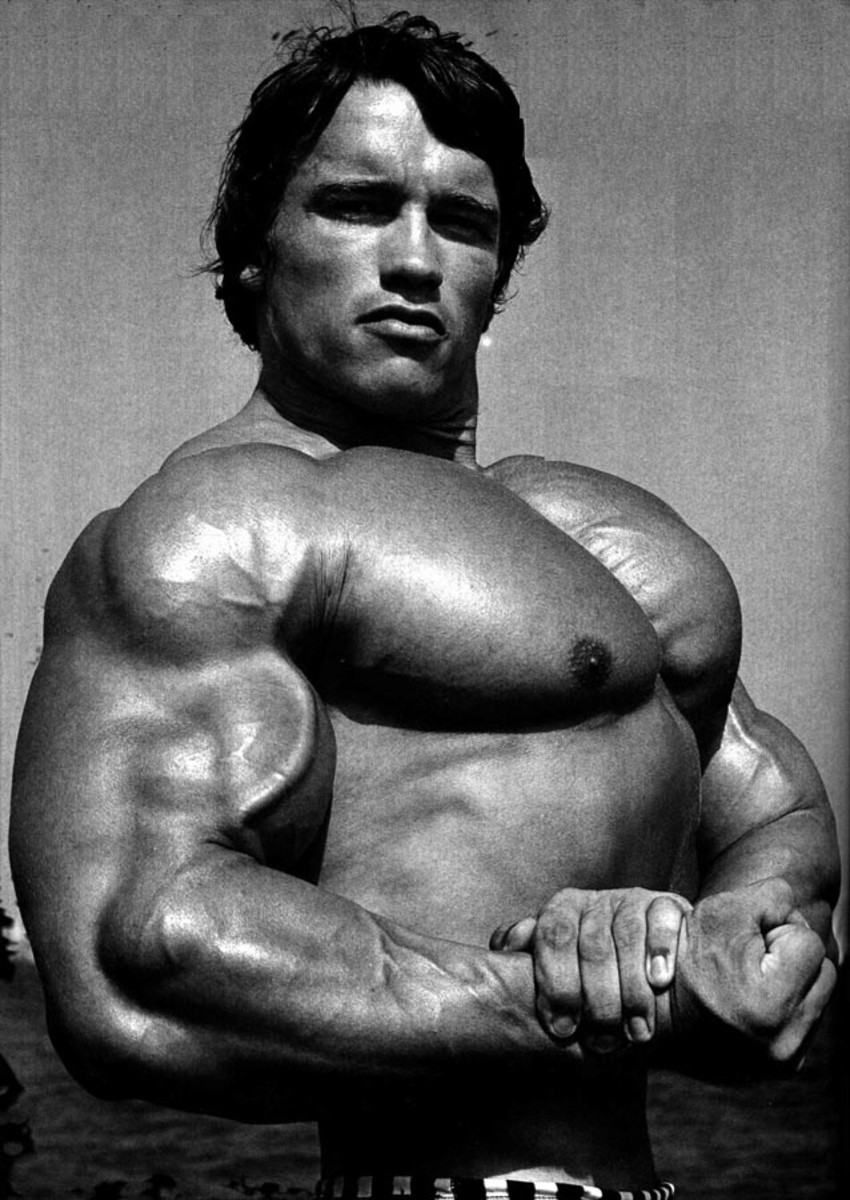

Food Folklore

Have you heard the one about carrots improving your night vision? I grew up believing this, and yet it stems from British WWII propaganda designed to confuse the Germans - which itself sounds like an urban legend because it's a pretty bizarre use of military intelligence! This article from Smithsonian Magazine reveals all, and paints a picture of social history during that era. Check it out:

A WWII Propaganda Campaign Popularized the Myth That Carrots Help You See in the Dark

But it wasn't just the British government that were at it - foodie fibs have often come from advertisers hawking their wares:

Eight of the most outlandish food health claims - Think today's faddy diets and superfoods are bad? In years gone by, the public was told that Coca-Cola cures impotence, biscuits prevent masturbation and pomegranate juice helps you cheat death.

Also take a look at The Angry Chef's website - it's funny, informative, and 100% fiction-free:

The Angry Chef - Exposing lies, pretensions and stupidity in the world of food.

The truth is that nonsense claims about food are everywhere. From old wives' tales, to celebrity juice cleanses, to wellness gurus. But some of it, albeit a tiny fraction of the overwhelming torrent of drivel, is backed by science. Lets begin with so-called superfoods.

Superfoods

We hear a lot about so-called superfoods in the media, in fact the first page of Google search results for "superfoods" yielded all of these!

Every food is super!

beetroot

| blueberries

| broccoli

|

chocolate

| goji berries

| coffee

|

garlic

| green tea

| pomegranate

|

wheatgrass

| tomatoes

| kale

|

black beans

| salmon

| oats

|

acai berries

| seaweed

| chia seeds

|

mangosteens

| maca powder

| kefir

|

hemp seeds

| nutritional yeast

| greek yogurt

|

quinoa

| strawberries

| watermelon

|

spinach

| pistachios

| eggs

|

almonds

| ginger

| pumpkin

|

apples

| cranberries

| cauliflower

|

lentils

| kiwi fruit

| Swiss chard

|

collards

| mustards

| radish

|

cabbage

| sweet potato

| squash

|

sardines

| mackerel

| noni fruit

|

dragon fruit

| rambutan

| olives

|

prunes

| walnut

| Brussels sprouts

|

bok choy

| avocado

| scallops

|

brown rice

| oysters

| edamame

|

bran flakes

| sunflower seeds

| asparagus

|

bananas

| skimmed milk

| potatoes

|

flaxseed

| cherries

| wheatgerm

|

black tea

| peanut butter

| blackberries

|

grapes

| soya milk

| Brazil nuts

|

canola oil

| oranges

| watercress

|

turkey

| barley

| shiitake mushrooms

|

seabuckthorn

| baobab

| papaya

|

raspberries

| black pepper

| mint

|

fish oil

| pineapple

| sauerkraut

|

water

| spirulina

| parsley

|

olive oil

| grapefruit

| arugula

|

coconut oil

| carrots

| mulberries

|

cilantro

| buckwheat pasta

| onion

|

mango

| honey

| turmeric

|

I'd not heard of many of these, and that is one of the tools in the superfood marketing toolbox - if it sounds a bit exotic, it's likely to attract attention, can be linked to some ancient wisdom claim, and the consumer just doesn't know any better.

Something's not right here...

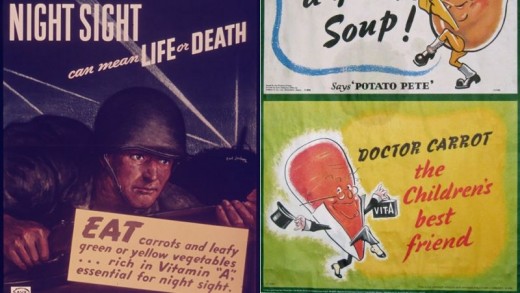

That's a lot of foods claiming to have some miracle health benefit. Surely with that ubiquity we'd all be living to 120? Funnily enough, that list constitutes all the ingredients necessary for a healthy and balanced diet, which is kind of the point - bingeing on a single foodstuff isn't going to bring you much benefit. If you eat one food to the exclusion of others, you risk becoming malnourished, and if you consume more of a vitamin or mineral than your body needs, it just ends up flushed down the loo. Your body can't store it or use it all up in one go. Interestingly enough, large quantities of Vitamin C are known to cause diarrhoea. Enjoy that mango smoothie!

You HAVE to click on the link in the source. It's so weird!

What's Super About Superfoods?

Not very much. There is no legal or scientific definition of a superfood, although it is widely understood to mean "a nutrient-rich food considered to be especially beneficial for health and well-being" (Source: Oxford Dictionaries). Cancer Research UK says that "the term ‘superfood’ is really just a marketing tool, with little scientific basis" (Source). Due to the strict food labelling laws that we have in the EU, the term "superfood" can only be used on food packaging or advertising if it relates to a specific health claim as permitted by the categories in the legislation. These permitted categories are quite narrow and prescriptive, so it makes the use of vague terms impossible: the types of claims allowed are very specific and don't allow for general terms like "superfood" or "improves brain health" unless the manufacturer can demonstrate that the product contains a particular nutrient that has been scientifically proven to show the claimed benefit.

The permitted health claims are related to the energy and nutrient content of the food, and a full list can be found here: European Commission | Food Safety | Food | Labelling and nutrition | Nutrition and Health Claims | Nutrition claims

To save you a little time, the main points are listed below.

What can go on the label?

Energy Content

| Nutrient Content

|

|---|---|

The energy it provides, e.g. '100 calories per slice'

| The nutrient or other substance that it contains, e.g. 'contains Vitamin B12'

|

The energy it provides at a reduced or increased rate, e.g. 'reduced calorie'

| The nutrient or other substance that it contains in reduced or increased proportions, e.g. 'reduced salt'

|

The energy it does not provide, e.g. 'calorie-free'

| The nutrient or other substance that it does not contain, e.g. 'fat-free'

|

The permitted health claims fall into three categories:

1. 'Function Health Claims',

- Relating to the growth, development and functions of the body

- Referring to psychological and behavioural functions

- On slimming or weight-control

2. 'Risk Reduction Claims' on reducing a risk factor in the development of a disease.

3. 'Claims referring to children's development'.

There is more information on the criteria for falling into one of these three categories in the following link. It does go into quite a lot of detail, but you get the idea; if it ain't backed by science, it ain't going on the label.

As you've probably figured out by now, there is very little that we can legitimately call a superfood.

So why so much hype about superfoods?

While suppliers, retailers and advertisers are forbidden from making outlandish health claims related to their products, TV programmes, books, and health & wellness websites can be a lot less cautious in their approach. These ideas don't come out of nowhere - people are publishing and distributing this information, usually to sell a product. Because there's a separate industry devoted to promoting this stuff, merchants don't need to make these claims. All the health food shop needs to do is state that they sell certain products, and people will buy it because there is not just advertising, but a lifestyle to buy into.

Wellness Means Wealth-ness (for the salesperson)

![The global wellness industry is worth $3.7 trillion [source: https://www.globalwellnessinstitute.org/press-room/statistics-and-facts]. That's a lot of kale smoothies. The global wellness industry is worth $3.7 trillion [source: https://www.globalwellnessinstitute.org/press-room/statistics-and-facts]. That's a lot of kale smoothies.](https://usercontent1.hubstatic.com/13617388_f520.jpg)

How Do We Know Which Reports To Trust?

There are some illnesses that can lead people to rely heavily on one type of food at the exclusion of others. But most people eat lots of different foods, and don't take part in randomised controlled trials. That makes any anecdotal evidence weak, and adds difficulties in pinpointing specific benefits in people who eat varied diets. However, there are some types of long-term study that can assess the effect of a change in diet or inclusion / exclusion of a particular nutrient (cohort studies), and we can also consider the results of laboratory studies - but there are pitfalls. Generally press reports tell nothing like the whole story, and the only way to know what a study yielded (or was even designed to test for), is to read the scientific paper yourself. Not everyone has a background in academia or statistics, and without the right analytical skills, it's difficult to interpret the results (and probably quite tedious). There are some pointers for what to look out for, though:

Confounding factors - when an external factor that the experiment didn't account for, has an effect on the results, implying causation when there is none. e.g. it has been shown that those who drink a glass of red wine each day are at reduced risk of heart disease. But... those who are more affluent, and by extension in better general health, are the demographic most likely to drink red wine daily, so it might not be the wine that's causing the benefit.

Self-reporting studies - people's memories and levels of bias can affect the results for all kinds of reasons; ranging from underestimating portion size, to giving the interviewer the response they think they want to see. Additionally these studies involve a much larger degree of subjectivity than something that can be measured, such as a blood test result.

Proxy outcomes - sometimes when we test a hypothesis, it's not possible to directly measure the thing we're researching. But we might be able to test for a different variable that suggests the variable in question is affected in the same way. For example, analysing the width of tree rings as a proxy for climate conditions in each year of the tree's growth. The problem occurs if the two variables do not actually correlate, or if the proxy variable actually measures a confounding factor; then the experiment suggests an association when there is none.

Extrapolating from laboratory & animal studies - while experiments in the lab and/or on animals do give us useful information, care needs to be taken when applying the results to humans. There are a number of reasons why the results of lab studies do not necessarily apply to real-life situations, and why animal studies don't always apply to humans. These types of experiment are a springboard for further studies in humans; by themselves they don't always represent actual outcomes.

Dosage and exposure - an experiment in the lab may expose an animal to excessive or lethal doses of a substance, well above the equivalent dosage that would reasonably apply to humans. But without this information, it is easy (far too easy!) to infer that an experiment has demonstrated the toxicity of a substance, when in reality humans would never come into contact with a dosage of that magnitude. Everything is toxic in great enough quantities, even water.

Sample size - the optimum sample size for an experiment is a trade-off between cost and accuracy. Excessively large samples don't add anything to accuracy, but waste resources in duplicating data points. Samples that are too small sacrifice accuracy because they do not include enough subjects to be representative of the population they are selected from.

Funding & independence - any scientist worth their salt will (and must) disclose potential conflicts of interest, including where they obtained funding (I'm funding my own research so only have my own implicit biases to blame). But it's not always clear in press reports (partly for brevity's sake). Be on your guard: there are have been cancer studies funded by the tobacco industry, climate change studies funded by oil companies, and nutrition studies funded by manufacturers of sugary products. No prizes for guessing what the conclusions of those reports were.

Researcher bias - this can be very subtle, but is ultimately driven by the experimenter knowing the result they'd like to see, and unknowingly influencing the experimental design and execution to be more likely to yield that result.

Preliminary results - is this the first study that's been undertaken on the subject? Are there any other reports that confirm this result? Does there need to be further work carried out to put the result in context?

Cherry-picked studies - this is a deliberate choice to misrepresent the data. There could be 300 studies that give one result, but a report might select the one that doesn't to suit its agenda. Consensus is important, as is replicability. One study by itself is not enough.

Poor experimental methodology & control - this can be very difficult to spot without reading the original paper from which the claim is taken, and having an understanding of how a good experiment of this type should be conducted. Often, public awareness of this problem only occurs much later when other scientists have attempted to repeat the experiment, or have reviewed the original experimenter's methods. A famous example of this is the controversy over the alleged carcinogenicity of phenylalanine, derived from poorly-controlled experiments on rats.

And Don't Even Bother With The Tabloid Press

If you believe what the papers say, you're just one bacon sandwich away from certain death. Or immortality, depending on which study is being touted as the absolute truth this week. For a demonstration of this culinary contradiction, check out this list of substances that allegedly cause and/or cure cancer, according to the Daily Mail:

Kill Or Cure? Help to make sense of the Daily Mail’s ongoing effort to classify every inanimate object into those that cause cancer and those that prevent it. Check out the list of things that both cause and cure cancer - new items added all the time!

So, it has come to this.

Some foods that do have an exceptional benefit

What does the science say?

As has been pointed out several times in the text above, there are hardly any foods that can perform nutritional magic. But there are some interesting examples of foods that may exhibit useful and unique benefits. The studies that have been completed to date are subject to the same pitfalls as others, but we can only go on the available evidence, and there is scope for further inquiry.

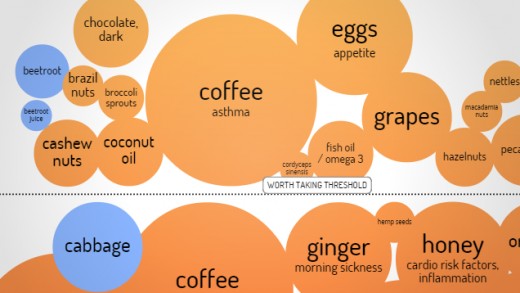

Snake Oil Superfoods?

The image above contains a link to an infographic at Information Is Beautiful, which ranks so-called superfoods on the available scientific evidence. If you hover over each food's name, you can see more information on the claimed benefit, and links to the related studies. What's important is that the claims are specific and graded in terms of how strong the evidence is.

What foods should I worry about?

You shouldn't worry about any one single food in isolation, the same as you shouldn't try to consume more of any one single food to the exclusion of others. Increasing the amount of so-called superfoods in your diet likely won't do you any harm, and because most of them are plant-based, there's going to be an overall benefit in respect of getting more fibre and more varied nutrients into your system.

But there are some elements of our diet that we do need to be worried about. The World Health Organisation has identified the greatest risks to health from food as:

- cancer

- diabetes

- cardiovascular disease

- obesity

- osteoporosis

- dental disease

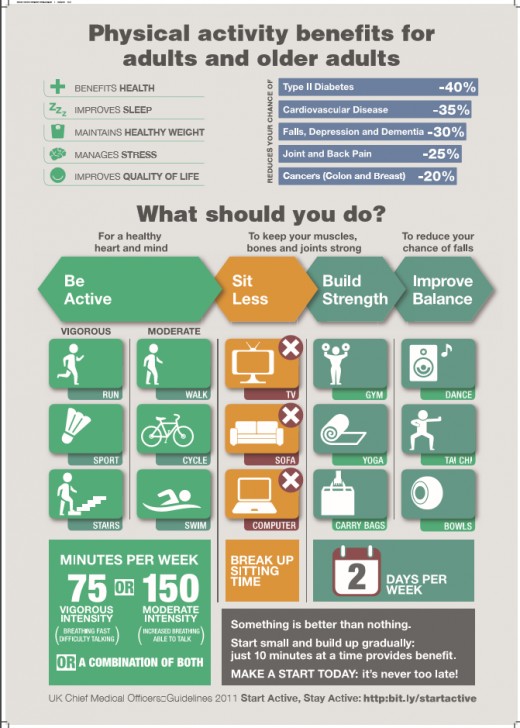

Physical inactivity also has a role to play in many of these, and the message is clear: consuming too much high-calorie, high-sugar, & high-fat foods can lead to chronic conditions that are preventable not through eating miracle superfoods, but an overall balanced & healthy diet. Making minute changes in the form of increasing a single ingredient is tinkering around the edges at best; we need to focus on the bigger problems of unhealthy lifestyle and diet.

Diet facts and evidence | Cancer Research UK

Eating more fruits and vegetables may prevent millions of premature deaths | Imperial College

What should I eat as part of a healthy diet?

You need to consider three things:

- The calorie & nutrient content of your food,

- What types of food you consume,

- How much exercise you do.

Guideline Daily Amounts

Typical Values

| Women

| Men

| Children (5 - 10 years)

|

|---|---|---|---|

Calories

| 2000

| 2500

| 1800

|

Protein

| 45g

| 55g

| 24g

|

Carbohydrate

| 230g

| 300g

| 220g

|

Sugars

| 90g

| 120g

| 85g

|

Fat

| 70g

| 95g

| 70g

|

Saturates

| 20g

| 30g

| 20g

|

Fibre

| 24g

| 24g

| 15g

|

Salt

| 6g

| 6g

| 4g

|

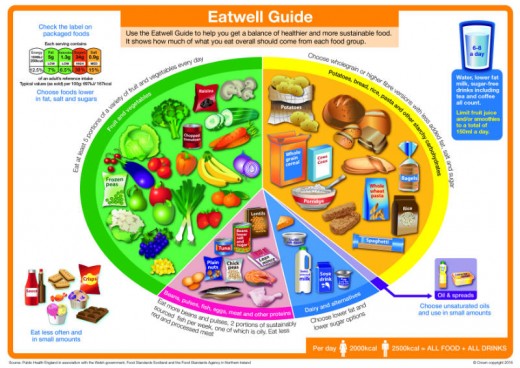

The Eatwell Guide

How Much Exercise Do I Need?

The guidance above is a good starting point to work towards a healthier lifestyle. If you are able to do that and stick to it, you're doing the best you can to prevent illness now and later in life. Of course, everybody is different, and if you don't think that your body matches that of the 'average' adult, you can adjust the values to suit you. The advice can be boiled down to "eat good food, do some exercise" if you're not about the numbers. Too much or too little of most things unhealthy, so keep it in moderation!

If you want to work out your recommended calorie intake, use this calorie calculator. It takes into consideration your height, weight, and activity level.

To Summarise:

- There's no such thing as a superfood

- You need to eat a healthy and balanced diet

- Don't eat too much, or too little

- Do some exercise

And that's it! Wow, that is so much easier than juicing your entire food intake!

Ain't No Disputing This Food Fact:

Further Reading

You may be interested in the following links:

10 foods touted as health miracles, then vilified as health hazards - salon.com

What are superfoods? - NHS Choices

The Pool - Health - When the cult of “wellness” becomes unhealthy

And Remember...

...take all food health claims with a pinch of salt!

© 2017 Katy Preen