Stress and Heart Disease

What Are the Terms?

Heart Disease

Before discussing the link between stress and heart disease, we must operationalize (define the terms) stress. The reason for this is that when one does a literature search in PubMed using the search terms “stress and heart disease” one will get nearly 40,000 references. The outcome of stress contributing to cardiovascular disease has been defined as vital exhaustion, oxidative stress, increased risk of psychiatric disorders, or multiple other physical stressors that impact cardiovascular functioning. This paper will discuss the effects of chronic psychological stress and its effect on cardiovascular functioning (the ability of the heart and cardiovascular system to work properly).

Stress

Psychological stress has also been difficult to define as basically because there is no objective measure of such stress. Perhaps the classic approaches are the best. Hans Seyle (1956) defined a stressful event as one in which an environmental demand surpasses the inherent regulatory capacity of the organism. Seyle also defined a psychological model of the reaction to prolonged stress, the General Adaptation Syndrome, that is still referenced today (Seyle, 1956). First the organism experiences a state of Alarm in response to a stressful event and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis) is activated. If stressor persists the body attempts to adapt to the demands of the situation via hormone release and goes into the Resistance stage. This stage cannot be maintained indefinitely and eventually the organism’s resources will become depleted (Exhaustion stage). Early autonomic nervous system symptoms may appear such as perspiration, increased heart rate, and others. Eventually if the stress continues etc long-term bodily damage may occur in one or more systems including the cardiovascular system via decompensation.

Others, such as Lazurus (1966) added the notion that in order for something to be stressful it must be accompanied by a cognitive appraisal as being potentially threatening and that one does not have the resources to cope with the threat. This cognitive element of stress is extremely important because it helps explain the subjective notion of stress as well as the effects of stress on the body. Thus, we will define psychological stress as an event where the perception of the person) is that its demands exceed the person’s coping abilities and is chronic (as opposed to an acute event).

Psychological stress affects individuals in many ways.

Physical Reactions to Stress

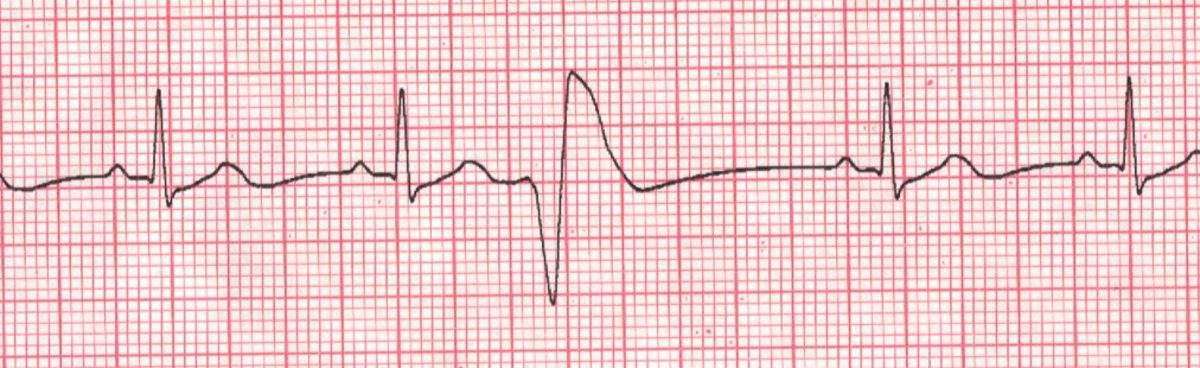

The physical response to stress has been recorded in a number of body systems, but the HPA response to stress is most often discussed as it leads to a cascade of detrimental effects in other bodily systems. The HPA response to stress is organized hierarchically: Stress leads to increases in hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) secretion that leads to a release from the pituitary of adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) and finally leads to the adrenocortical release of cortisol. In people with chronic stress there is a hypersecretion of CRF (which is determined via levels of CRF in cerebrospinal fluid and a dulled ACTH response to CRF stimulation (Miller, Chen, & Zhou, 2007). These abnormal circadian cortisol cycles are also linked with fatigue, vulnerability to a number of health issues, and poor motivation (Miller et al., 2007). Thus, chronic stress results in hypersecretion of CRF and adrenocortical hypoactivity. This leads to persistent hyperactivity of the HPA axis and chronic over-activity of CRF-containing neurons in limbic and hypothalamic brain regions and under-activity in other brain areas. Anatomical connections between brain areas such as the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and amygdala, facilitate the activation of the HPA axis (Miller et al, 2007).

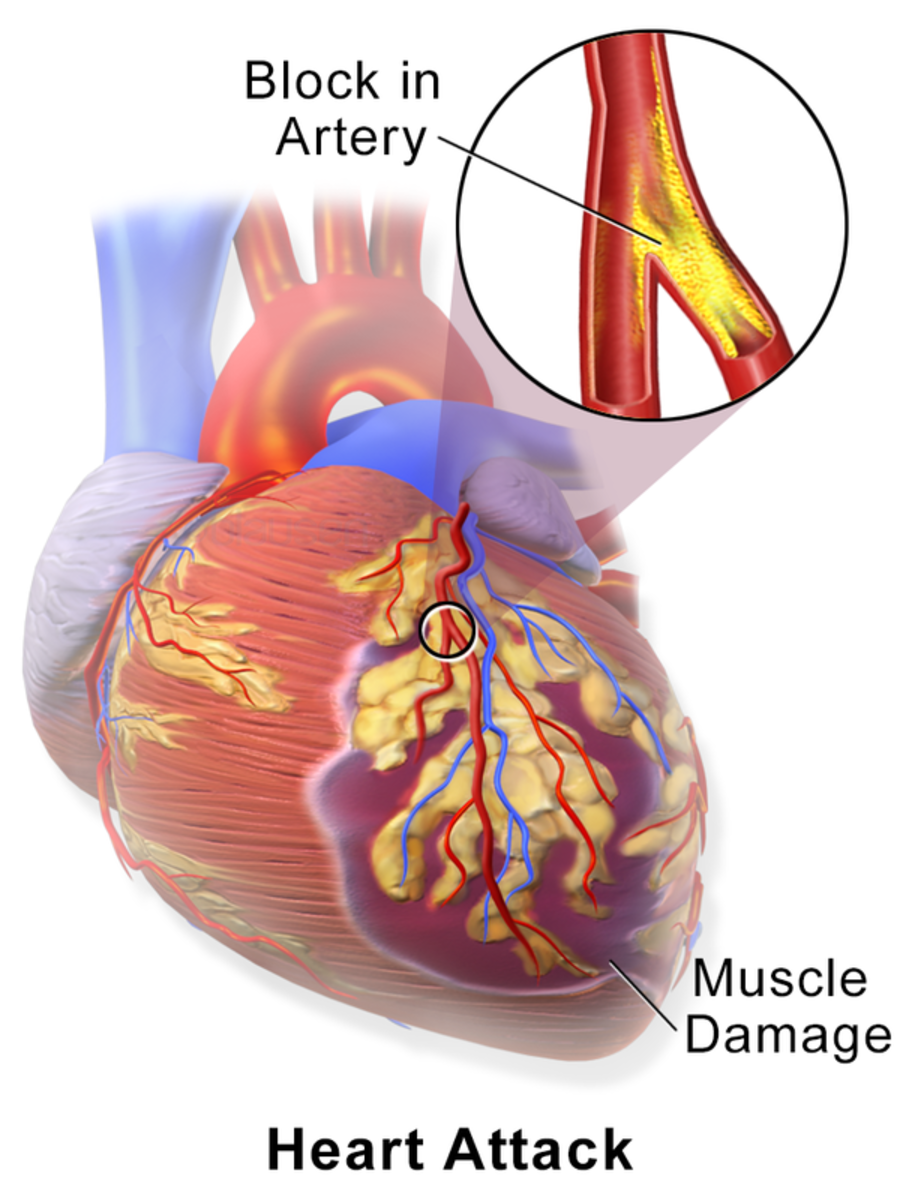

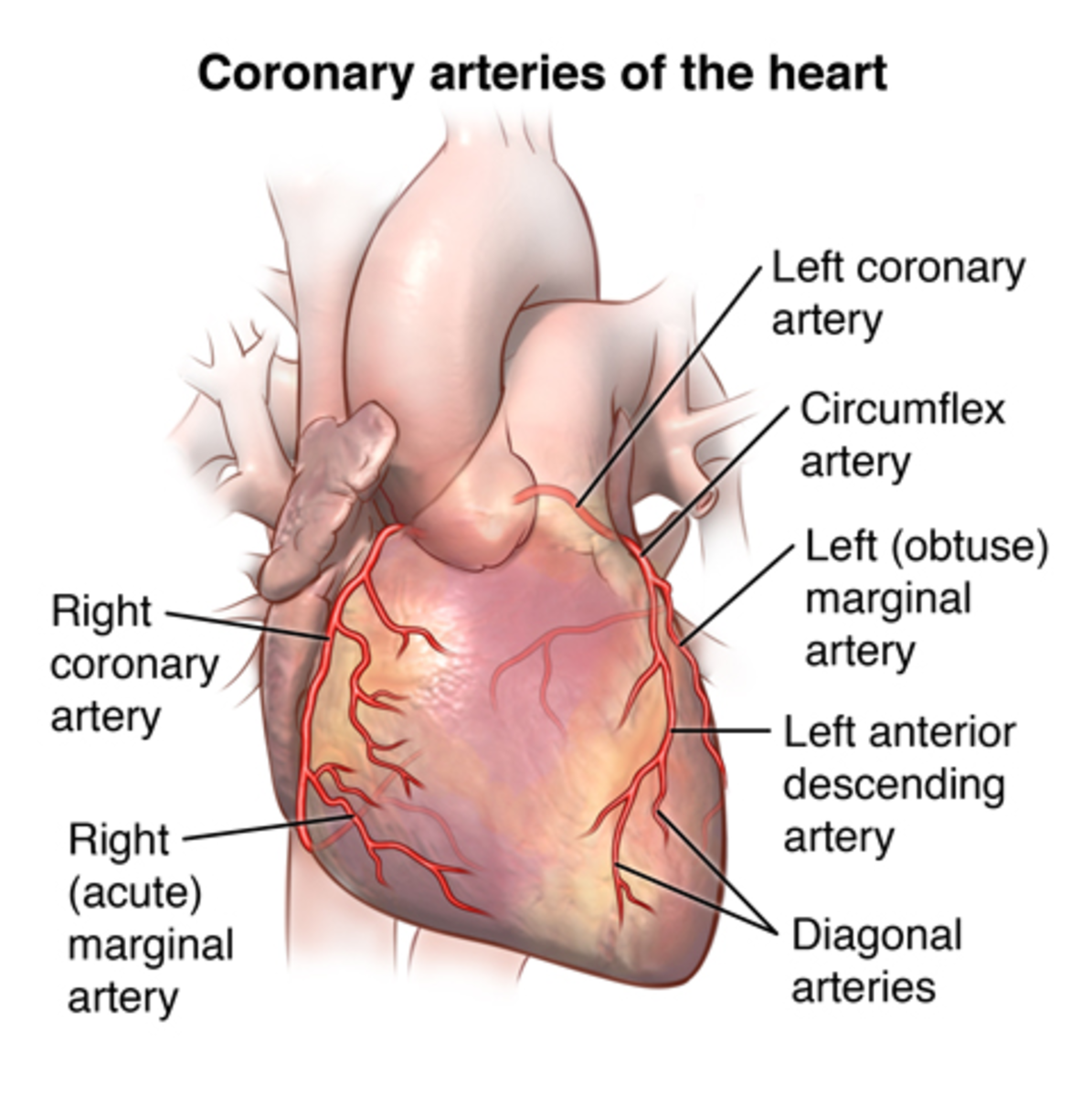

Moreover, other pathways that are affected by stress have been discovered. For example, both animal and human and studies have demonstrated that stress leads to alternations in the mechanisms involving blood flow. In these studies, psychological stress and coronary artery disease combine to reduce blood flow. This occurs mainly via coronary artery spasm or artery constriction as a result of endothelial (the inner lining of the artery) dysfunction (Smith & Ruiz, 2002). Consequently, stress can lead to major vulnerability factors via several routes that affect the cardiovascular system.

Rosengren et al. (2004) investigated the relationship between chronic stressors to incidence of myocardial infarction (MI) in a sample of nearly 25,000 individuals from 262 medical centers in 52 countries. Stress was defined broadly but was assessed over four different areas. After adjusting for gender, age, smoking habits, and geographic region it was found that those who had suffered a MI reported significantly more stress over all four areas. Chronic stress at work or at home was associated with over two times the risk for developing an MI in the sample. Of course this study is correlational. One potential issue is that after having an MI the person looks back on their life and assesses what issues (stress, diet, habits, etc.) that could have “caused” the event. Thus, such self-report data is inherently confounded. Some studies have attempted to prospectively assess stress levels and then follow large samples and record the incidence of cardiac events.

Work-related stress has been operationalized in some studies as occurring in positions that have high demands but offer workers little control over their situation. There have been several studies that have followed this route. For instance, Theorell et al. (1998) studied males who were 45 to 64 years old and who had been working full time (defined as greater than 35 hours per week). First-time MI suffers were significantly more likely to have high work demands and low personal control. Bosma, Peter, Siegrist, and, Marmot (1998) found a two fold increase in the risk for new coronary heart disease in men who worked in jobs where they put in high effort and received low or little rewards for their efforts. There was an interaction between the aspects of the job and personality factors such that the high-risk subjects were more likely to be hostile, competitive, and overcommitted to their jobs despite a lack of or poor promotion prospects and low levels of acknowledgement for their efforts. Thus, the connection between stress and MI could be mediated by other factors.

Stress and Heart Disease

With respect to non-job related stress and cardiovascular problems, several areas have been studied. For instance, millions of people are caregivers for a family member or other person. One of the most common of these situations involves someone who cares for a spouse with dementia. This is quite distressing as continuous downward course of the patient is extremely stressful for the caregiver. Schulz and Beach (1999) followed 400 such caregivers and 400 matched controls over a four year period. The caregivers exhibited a 63% higher mortality rate compared to the controls and this increased mortality was predominantly evident in the caregivers who suffered from previously documented cardiovascular disease. Shaw et al. (1999) followed these caregivers over a six year period and found that the distressed caregivers had an increased risk for developing hypertension, which of course could contribute to cardiac disease. Von Kanel et al. (2005) found that distressed caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients exhibit greater sleep disturbances, elevated D-dimer levels (which is a procoagulant factor), and higher levels of plasma inflammatory cytokines, all of which contribute to MI.

Many other studies have documented the relationship of chronic stress to cardiovascular disease in human subjects and in animal models that allow for manipulation of variables not possible with human subjects (e.g., Smith & Ruiz, 2002). However, there are several caveats to these findings that need to be considered:

- The data is not conclusive regarding the relationship between stress and cardiovascular disease. For instance, it would be wrong to state that “stress causes heart disease” based on empirical findings in human populations. Stress is a risk factor that increases the probability of cardiovascular in some populations. However, it has been long recognized that stress can increase the probability of other health-related issues and not heart disease (e.g., Seyle, 1956). This is markedly different than a casual effect. Moreover, the exact mediating variables that interact with stress have not been determined. For instance personality variables appear to interact with stress in increasing the risk of cardiovascular disease.

- As a risk factor for heart disease stress appears to be as important as other risk factors such as cholesterol levels, but not as robust as risk factors such as smoking (Siahpush & Carlin, 2007). Moreover, risk factors like smoking are known to decrease stress, and yet they increase the risk of heart disease and MI. Studies often control for behaviors like smoking when testing the effects of stress. Thus, stress has to be examined in terms of how it modifies other behaviors that are risk factors for health issues.

- Stress is everywhere, but the crucial factor regarding the effect of stress appears to be the perceptions of the sufferer. Thus, the type of stressor appears to be less of a factor than the reaction of the sufferer. Because stress is so prevalent we should not operate under the assumption that is cannot be modified like genetics or age. It is important to recognize that stress can be modified and its effects diminished. Perhaps the real benefit to identifying stress as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease is that there are ways to decrease stress which have been demonstrated to decrease the risk of MI.

The cardiovascular response to stress appears real, exquisitely complicated, and modifiable to a point. When a significant stressor continues or the person broods there are potential adverse cardiac issues and other health problems. But stress is not specific in its effects; that is that some people may experience ulcers, others heart issues, and others may have other health-related effects from stress. Since the effects of stress are potentially modifiable, high risk populations should receive assistance altering their behaviors and altering their cognitions.

References

Bosma, H., Peter, R., Siegrist, J., & Marmot, M. (1998). Two alternative job stress models and the risk of coronary artery disease. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 68–74.

Lazarus, R.S. (1966). Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Miller, G. E., Chen, E., & Zhou, E. S. (2007). If it goes up, must it come down? Chronic stress

and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis in humans. Psychological Bulletin 133

(1), 25-45.

Rosengren, A., Hawken, S., Ôunpuu, S., Sliwa, K., Zubaid, M., Almahmeed, W. A., Blackett, K. N., Sitthi-amorn, C., Sato, H., & Yusuf, S. (2004). Association of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocardial infarction in 11,119 cases and 13,646 controls from 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet, 364,953-962.

Schulz, R. & Beach, S. (1999). Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The caregiver health effects study. JAMA, 282, 2215–2219.

Seyle, H. (1956). The stress of life. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Shaw, W., Patterson, T., Ziegler, M., Dimsdale, J., & Grant, I. (1999). Accelerated risk of hypertensive blood pressure recordings among Alzheimer caregivers. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 46, 215-227.

Siahpush, M. & Carlin, J.B. (2007). Financial stress, smoking cessation and relapse: Results from a prospective study of an Australian national sample. Addiction, 101, 121-127.

Smith, T.W. & Ruiz, J.M. (2002). Psychosocial influences on the development and course of coronary heart disease: Current status and implications for research and practice. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 548-568.

Theorell, T., Tsutsumi, A., Hallqist, J., Reuterwall, C., Hogstedt, C., Fredlund, P., Emlund, N., & Johnson, J. J. (1998). Decision latitude, job strain, and myocardial infarction: A study of working men in Stockholm. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 382–388.

Von Kanel, R., Dimsdale, J., Adler, K., Patterson, T., Mills, P., & Grant I. (2005). Exaggerated plasma fibrin formation (D-dimer) in elderly Alzheimer caregivers as compared to non- caregiving controls. Gerontology, 51, 17-13.