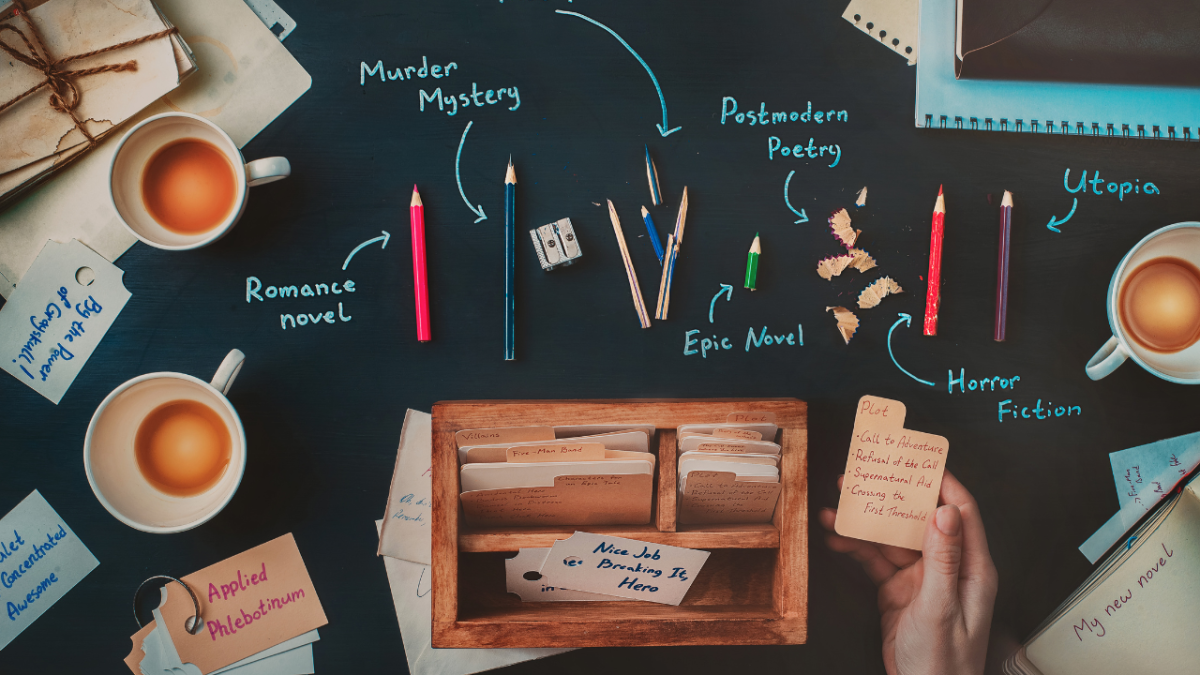

Plot, Character or Both? Fiction Writing Basics

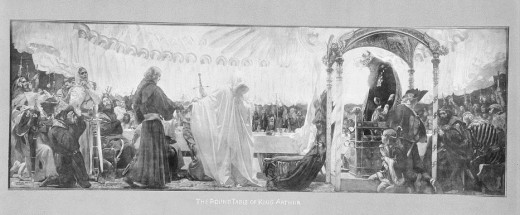

The early epics

Throughout literary history, writers have created works of literature that are either plot-based or character-based. The earliest epics like the Iliad and the Odyssey, Song of Roland, and Beowulf, though bursting with adventures, focused on heroic characters and their humanity. We remember Achilles, Odysseus, Roland, and Beowulf as people, and while we might forget all of their many accomplishments, we can still see and hear them in our minds.

Medieval romance

The later heroes in medieval romance like Lancelot, Tristam, and Percival, were not nearly as important as the adventures they had. As Dr. Charles Baldwin wrote, “They are habitually and typically personages rather than persons.” We are far less interested in their character than we are of their heroic actions. We want them to save the damsel, slay the dragon, and find the Holy Grail. We’re not as interested in how they feel about killing a dragon or whether the relationship with their mothers spurred them to rescue the damsel or they feel any angst at finding the Holy Grail. Many of us could retell these stories from start to finish, but how often could we remember which particular knight did which daring deed? These romantic knights were caricatures instead of characters, merely human bodies going through heroic motions.

Much of modern fiction—if not all—falls into these two basic categories: plot-driven or character-driven. Why can’t fiction be both? Can fiction be both? Is there a formula for synthesizing the two?

Character-driven fiction

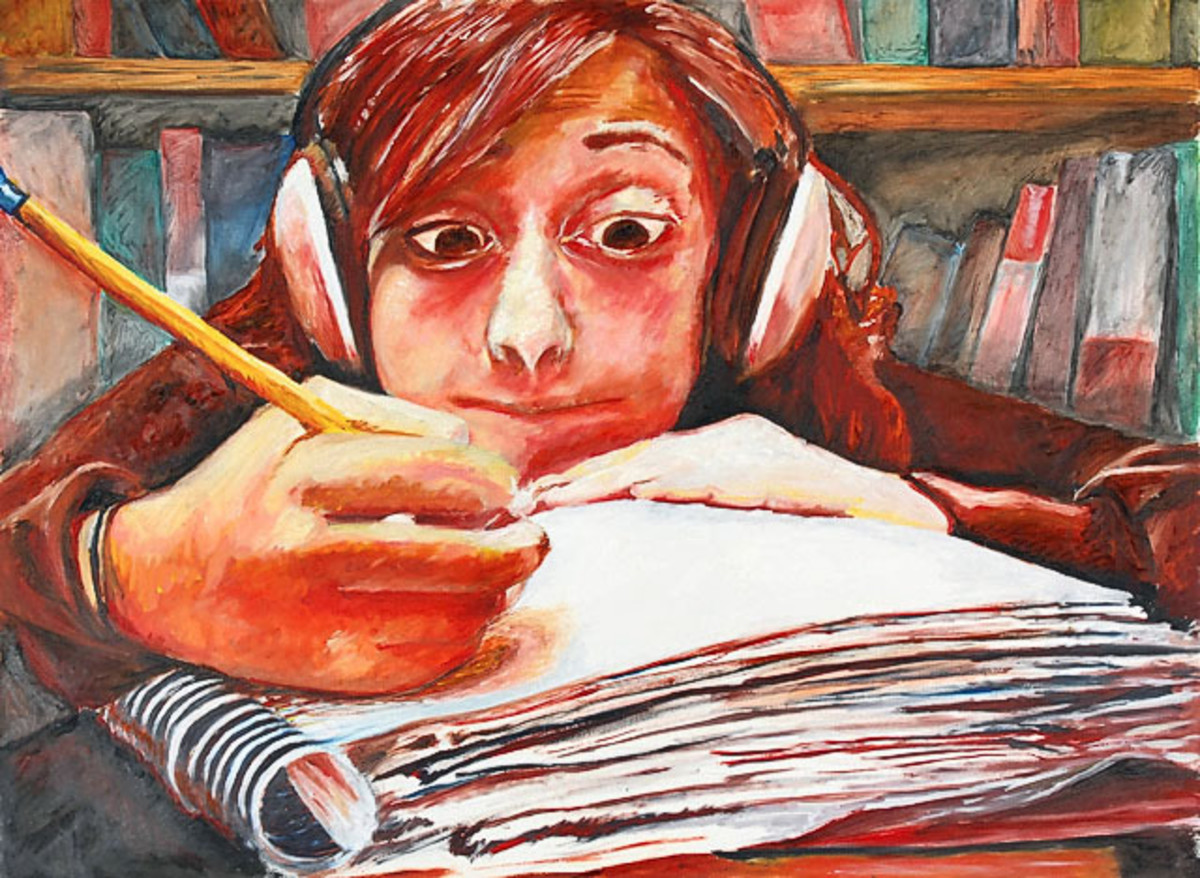

In character-driven fiction, a character must appeal to us through speech, action, and gesture. A writer must express a character though significant actions and words, mannerisms, and even dialect. Writers don’t have time (unless they are reincarnations of James Joyce) to recreate the minutiae of daily life. Writers can also reveal a character by the reactions of other characters. Modern fiction writers like to delve into a character’s psyche, thoughts, dreams, and desires—myself included. However, sometimes going too deeply into a character’s mind isn’t that exciting for a reader. While it does reveal hidden facets and nuances of a character, it does not necessarily move the story along. Too much thought can ruin the plot!

The most skillful fiction writers reveal their main characters gradually over the course of the work. They give enough back story to get us going and then allow their character to move through the world of the narrative. They don’t give excruciating autobiographies from page one and then start the action forty pages later. They don’t tell us, “She was born on the fifth of May in Bayou Blue Parish, which was first settled by the French in 1727 and later inhabited by the Chickasaw, who fought a long and protracted battle with the Cajuns over crayfish trapping rights, a fight that continued until she was two and climbing weeping willows better than any girl in Louisiana.” They leap to an inciting incident, a moment later in her life that establishes the kind of woman she has become. Her past might indeed be a key to her present state, but the past shouldn’t dominate the action from the beginning. Readers want to read about the here and now when they read page one.

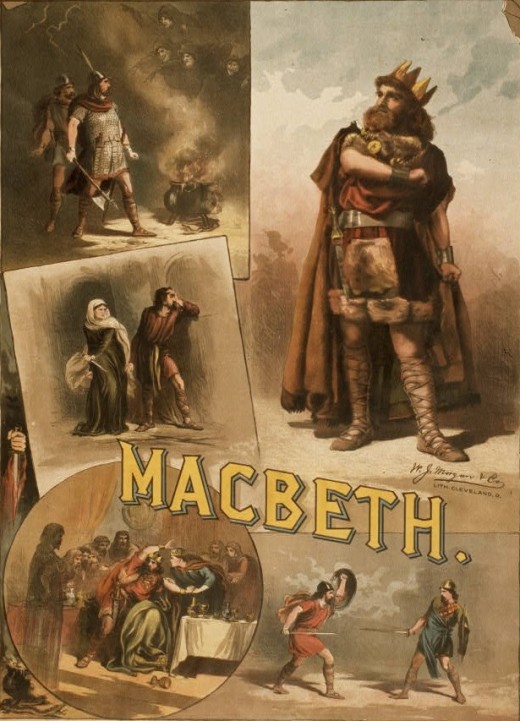

When we first meet Macbeth, for example, he and Banquo have just come from a victorious though bloody battle. We don’t know Macbeth’s history, who he’s married to, where he was born, what his dog’s name was, what he enjoys eating on Thursdays, or what motivates him to get out of bed in the morning. We only know that he’s a tired soldier and loyal friend—and then he meets the witches whose prophecies ruin the rest of his life. Shakespeare’s play takes off immediately from this incident, and we see how Macbeth gradually changes for the worse because of those prophecies and meets a tragic end.

If we drop our main character into the middle of things, or in medias res as most of the old epics begin, not only do we allow our readers to get a snapshot of our main character, but we immediately begin the action as well. And once the action heats up, we can reveal more and more of our character. In other words, the action fuels the character fueling the action. The character makes things happen, and the things that happen make the character come to life.

Plot-driven fiction

I believe that every story should move toward one main event. Teachers like me have called these main events “climaxes” for ages. Whatever you wish to call them, what you write must have one specific destination. Thus, in plot-driven fiction, every word, action, gesture, scene, paragraph, and sentence must proceed to that main event or destination. The main event itself should be the first thing a fiction writer imagines before writing the first word. Without a specific ending in mind, a writer really has no story. A plot-driven writer must know where the story is ultimately going before he or she gets there.

I worked with a writer who had written 300,000 words with no ending in sight. “I want this to end!” she cried. I located a major main event about halfway through and wrote, “The end.” On the next page I wrote, “Book Two.” I then advised her to begin her sequel, which she did not originally intend to write, just after this major event. Many months later after some serious soul-searching and painful revisions, she had two novels with two amazing climaxes, and both are now selling briskly on Amazon.com. She had lost sight of her destination, but once she found her bearings, she realized she had written two exciting journeys, each with its own glorious climax.

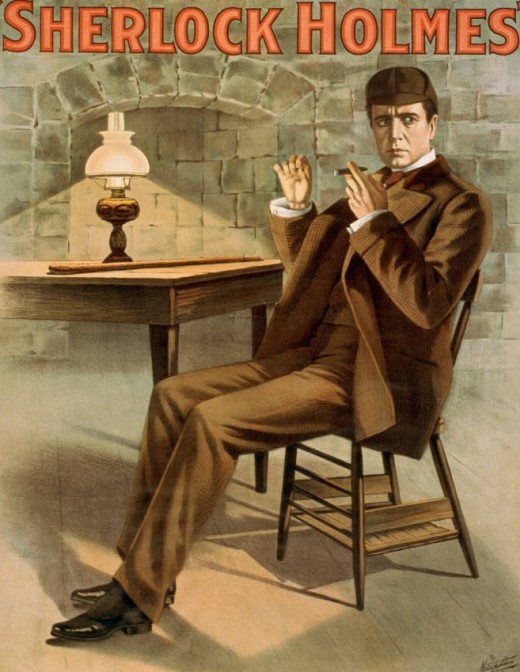

Writers of plot-driven fiction must spend inordinate amounts of time plotting their events. Some writers make timelines or cover their walls with Post-It’s full of dates and even times down to the minute. Writers of thrillers, for example, must whisk us along at a breakneck pace to a satisfying end, and each thrill should improve upon or top the one before. The climax, then, should never be a moral summing up of the action with one character going on and on and explaining every preceding event: “Mr. Johnson is the killer, and here are the many and various reasons why, and I shall tell you these reasons in laborious detail for the next thirty pages …” The climax should be a logical and artistic solution of everything that came before it. It should also contain the most action in the novel. How often have we closed a book and shrugged because the main event wasn’t that eventful? While the writing may have been stellar and the adventure pulse pounding, the ending left us sighing because it ended with a whimper instead of a bang. Save the best action for last, and your reader will appreciate the entire work.

Four steps to combine character and plot

How, then, do we create wonderful, interesting characters within action-filled fiction?

1. Put your main character immediately into an action scene on the first page.

Get our attention and begin developing empathy and even sympathy for your character while the character does something. It doesn’t have to be monumental, but the scene has to move. She pulls into a drive-through and tries to order the “healthiest” meal. He walks outside and notices someone has keyed his car. She tries to give reasons to her child on why it’s not nice to terrorize the cat with a fork. He sees a pretty woman and follows her into a coffee shop. Drop him or her into a scene and let them move.

2. Seamlessly move from this scene into another active scene, gradually letting us hear and see your character as he or she encounters more problems or meets new characters.

Occasionally drop in back story or background on your character, or let other characters provide this back story. A simple phone conversation, for example, can reveal so much about a character’s past while keeping the plot moving. I like mixing back story into simple walks around the neighborhood where my characters live. The reader sees the scenery, gets a decent idea of the setting, and “hears” my character’s thoughts simultaneously. If her phone should ring, the reader gets to see and hear yet another side of her character through her conversation.

Having a character simply scan his or her living space often reveals character: “She tossed her keys into an empty coffee mug, trashed a stack of mail except for a phone bill and a copy of Architectural Digest, and tripped once again on the seam in the carpet leading into her TV-less living room.” Without telling you, I’ve told you a great deal about her, haven’t I? Perhaps she no longer drinks coffee, or she drinks so much coffee that she has mugs to spare. Perhaps she’s an absentminded architect. She doesn’t own a TV? Who doesn’t own a TV? With one sentence, I’ve revealed what I want the reader to know—and created a bit of mystery in the process.

3. As you write, always keep your main event or climax in mind.

Remember your ultimate destination. Ask yourself, “Is this scene leading in some way to the main event? Or is this scene only helping to develop my character? If the scene is only a character study, do I really need it?” In other words, you have to ask yourself, “Is what I’m writing this second advancing the plot and revealing my character or not?” If it doesn’t do both, you need to get back on track so you don’t lose your reader’s attention.

4. When you reach the climax, make sure your character has changed or evolved since page one.

People change in real life when they go through trials and tribulations, so your character must change or evolve, too. If they begin as shy and withdrawn, they could be completely out of their shells by the climax. If they begin as proud and cocky, they could have tragic or humble ends. If they begin out of love and lonely, they could be in love and hooked up in the end. The reader must be able to see and feel how this character has survived the preceding pages. The main event must have a profound effect on the character. Otherwise, the main event—and the reader’s empathy and sympathy for the main character—will suffer greatly.

Stay focused and weld your character to the plot, and you will have an unforgettable character and an unforgettable climax—resulting in an unforgettable character-driven and plot-driven story.