France and the Coming of the Second World War Review

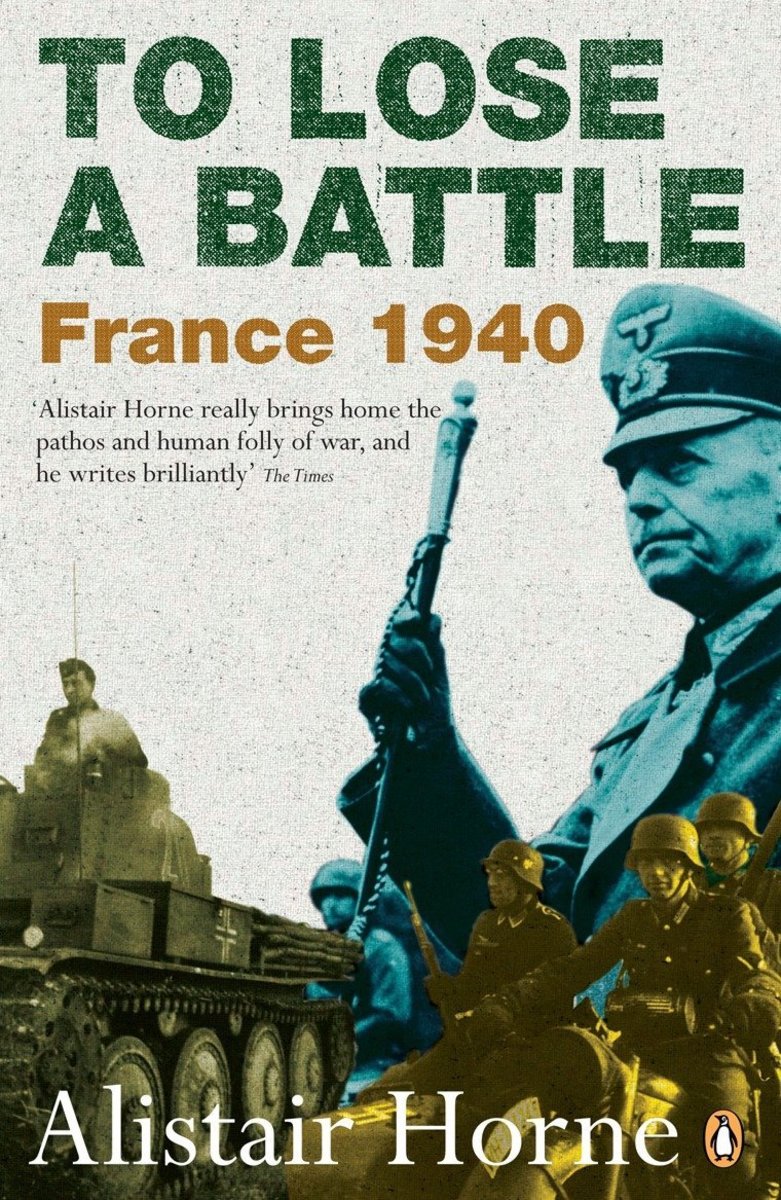

There is no topic in human history, I am convinced, which has been studied to the same extent that the Second World War has been. There have been so many books written about military operations, economics, diplomacy, politics, war crimes, and a million other subjects, that it resembles more of a deluge and flood than a literary press. But if there is one aspect of it which is somewhat less known, at least among the most popular ones, then it is the finer details of French diplomacy before the Second World War, which can be mostly boiled down to in popular conception to the French appeasing Germany out of fear of Hitler, and playing into stereotypes of French cowardice and tendency to surrender. History was hardly as simple as this of course, and was much more complicated and nuanced than this story. it is in examining this nuance and the more complete story of what happened in the 1930s in French diplomacy, that the book "France and the Coming of the Second World War, 1936-1939", by Anthony Adamthwaite. This book is becoming a rather aged one, from 1977, but still merits examination into whether it is a useful book to read to understand the subject.

Unsurprisingly, the book is organized roughly along chronological lines, starting with "The Setting", devoted to laying out the structure of France, fittingly labeled "Dilemma" as Chapter 1. France faced the problem of a stronger international stature than its own resources necessarily supported, making war catastrophic against Germany and lack of resistance meaning steady decline, while internal economic, political, and social struggles handicapped its political strength.

Chapter 2, "Quest for Security", covers the French attempt to assure their independence and interests against Germany, relying on the League of Nations for collective security, seeking to enforce treaties, and building up allies around Germany. They faced difficult limits to French power in problems like the Ruhr, the question of relations to Italy and whether it should be courted or opposed, the need for British friendship and alliance,and ultimately were only able to come up with half-way measures that did nothing to solve their problems.

Stemming from this, "Wit's end", Chapter 3,starts with the dramatic German occupation of the Rhineland in 1936, laying out the reasons for why the French did not intervene, and the Popular Front's trio of efforts to attempt to save French security - dealing with the Spanish civil war, reaching an understanding with Germany, and strengthening their Eastern alliances. All failed, and relations with Italy were poor over Ethiopia: the French government appeared to have no solutions to its domestic and external problems.

This led to a new strategy: "Wait and See", starting in Chapter 4, lays out the increasing French dependence on Britain and the passivity injected into French policy as a result, as the French increasingly had to come to grips with their incapability to protect their Eastern alliances and their inability for dynamic action.

The inevitable result of this occurred in Chapter 5, "Retreat" which covers French diplomacy concerning the Anschluss of Austria. Here, the French and British not only failed to cooperate to attempt to defend Austrian independence but generally relations declined afterwards, the French and Soviets proved incapable of cooperating, and Italy continued to remain hostile: Most importantly the internal situation continued to be shaky. In this context, continued French retreat and loss of influence in Central Europe seemed inevitable.

Part 2, Personnel of Machinery of Policy Making, takes a more detailed look at the individuals behind French foreign policy.

Chapter 6, "Enter Daladier and Bonnet", sees the previous Popular Front under Leon Blum fall, and a new government of Daladier, more to the right of the previous government, and Bonnet, his foreign minister eager for a rapprochement with Germany and friendly relations with Germany, take the reigns. Much of the chapter is dedicated to analyzing the two, who would go on to lead the country for the next few years until the outbreak of war and beyond, and it paints a much more positive image of Bonnet than is normally credited to him.

Chapter 7 "The Cabinet" discusses both the French governmental structure with its notoriously anarchical governments, French cabinets were much less stable, much less controlled, there were fewer institutional measures to coordinate policy, much more was ad hoc, and the prime minister was weaker, and strained under a general double role of controlling both the premiership and an important ministerial position. Under the strain, France's government started to slide towards authoritarian with national decrees serving to concentrate executive power into Daladier's hands, who used it ineffectually. The rest of the chapter dealt with various personalities found in the French government.

Chapter 8, "Parliament" takes a look at the French parliament, which was little involved in foreign policy. Although it sometimes did play a role, like during the occupation of rump Czechoslovakia, normally it was not even summoned during crises and left foreign policy to government initiative.

The French foreign ministry, named after its location in Paris, takes center stage in Chapter 9, "Quai d'Orsay", with its perspective on some of the key individuals involved in the French foreign ministry: here it tends away from a classification of those who were firm against Germany and those who favored appeasement, pointing out that the lines were much more fluid. Traditional diplomacy had been much weakened by the 1930s, but there was still a role to play in shaping public opinion and dealing with allies. In this regards, the foreign ministry

The final chapter of this section, chapter 10, "The Armed Forces", lays out the state of the French military, starting with some of its economic and spending elements and later going onto its organization, leadership, strategic balance, and the military's role in policy making.

The third section of the book returns to the chronological order, in "Undeclared War".

"Czechoslovakia, 1938", the 11th chapter, paints a picture of French diplomacy preparing to abandon Czechoslovakia, more eager to utilize it as a bargaining chip to secure closer ties with the British than to actually support its ally. Indeed, on multiple occasions the French would privately to the Czechoslovak government make it clear that they had no intent of actually fighting to defend their ally.

"Better Late than Never," Chapter 12, continues with the French efforts to avoid war while extracting British cooperation with them, ultimately leading to the Munich Conference. For France, the problem was how to secure peace without dishonor: this was achieved in tatters by the conference instead of simply a German occupation of the Czech territory. In France, public opinion greeted the event with delight, overjoyed to avoid another war, but it was only a precursor to future conflict.

Chapter 13, "Strategy and Diplomacy", looks at the military situation during the Sudetenland crisis itself, The French general staff had no intention of actually helping Czechoslovakia, and the French estimated the German air force as far more powerful than their own, with the Soviets, the only potential other factor to help, being dismissed for military, political, and ideological reasons. But the book makes the claim that even if France and Britain were more militarily powerful, it wouldn't have saved Czechoslovakia: the interest was in securing a European entente from a position of strength, not to fight another war.

The catastrophic strategic impact of the loss of Czechoslovakia as an ally is brought out in Chapter 14, "L'Effort Du Sang", with the quandry of what to do to replace the loss of the Czechoslovak ally. Here, it was clear that the only substitute was Britain, which would have to pay the blood price if it wanted to be able to keep France's support. This was amplified by war scares of German marches West. Meanwhile, relations with Italy continued to remain hostile, despite the end of the Spanish civil war and attempts at negotiation.

"A Free Hand in the East?", as chapter 15 is titled, saw the French return once again to a policy of wait and see: neither conclusively abandoning their remaining alliances in the East nor seeking to prop them up. The French were content to simply wait for the Germans to make their moves, and to attempt to channel them to peaceful and gradual expansion instead of military aggression.

"Penguins and Porpoises" Chapter 16, covers the final attempts to secure peaceful agreements with Germany, looking back at the Franco-German feud and post-war efforts about reconciliation. France and Germany did sign a pact expressing their friendly relations on December 7, 1939, but it was a hollow one, economic diplomacy failed, colonial concessions were opposed in France and infeasible, and cultural diplomacy amounted to nothing.

"A Change of Course", Chapter 17, relates the hardening of Franco-British attitudes towards Italy and Germany as a result of their occupations of Czechoslovakia and Albania. Britain finally introduced conscription and agreed to guarantee Poland against German aggression, but talks with Russia did not go well and the French Prime Minister continued his opposition to a rapprochement with Italy, despite Bonnet, the foreign minister's, intense interest.

"Calm Before the Storm", as is labeled Chapter 18, looks at the rather peaceful and uneventful few months preceding the outbreak of war. Appearances were deceiving: it was above all else because Hitler had abandoned attempts at diplomacy with France. Many French leaders still hoped for a detente but had no opening available. Other diplomatic tracks were applied, above all else attempts at reinvigorating alliances with Poland and the USSR, but the USSR negotiations constantly were wrecked upon the rocks of difficulties in strategic agreement between France, Britain, and the USSR and strategic incompatibility. With other powers, negotiations were slow, halting, or amounted to nothing, from Turkey, to Japan, to the US. And while relations with Britain had much improved, there remained quarrels over relations with Italy and military command in war-time.

Negotiations with Moscow are related in Chapter 19, "Last Days", which covers the ultimate debacle of Anglo-French-Soviet discussions, with the Anglo-French arriving late, negotiating ineffectually, and cooperating little. Poland too, refused to cooperate with the Soviets. Negotiations failed, the USSR turned to Germany instead, and the remainder of the chapter relates the last days of peace and the minutiae of the French lead up to the declaration of war on Germany.

The conclusion lays out the general lines of the book: that French appeasement politicians were genuinely interested in and believed peace to be necessary for France, that France was unwilling either to abandon her Eastern alliances nor fight for them, and that it was France's internal weaknesses which led to her inability to oppose Germany, predicated on the realistic assumption that another war would mean the end of France as a great power and a vast price to be paid for victory.

Diplomatic history has received some criticism over the last few decades, because it tends to focus above all else upon the actions of individuals, to miss the forest for the trees, to ignore structural factors and care too much about minutiae. This is essentially the case for France and the Coming of the Second World War, which also is what I see as a rather typical British history, since it focuses on individual personality and writes extensively about that. It makes for a book which is rather narrowly focused, sometimes tedious, which is neither revisionist nor mainstream, to a certain extent nondescript, lacking a major theorem or link to broader principles.

Some of this can be refreshing however. The book isn't really a revisionist book - its basic line is that the French wanted to avoid another war, and sought a diplomatic settlement with Germany that would lead to a lasting European peace. The foremost individual promoting such a strategy was Georges Bonnet, who has been roundly pilloried as gutless, spineless, morally bankrupt, cowardly, and dishonest. The book doesn't completely exonerate Bonnet, who is is noted as being rather a dishonest figure himself, especially in his post-war memoirs, But it does note that Bonnet was hardly a cowardly or irrational man, but instead driven by a consistent and logical program, the belief that France desperately needed to secure a rapprochement with Germany and to prevent another war. In this, it portrays a more balanced and nuanced perspective of French individuals advocating appeasement than what is often perceived.

It also includes a number of fascinating small details that make up the real benefit of such a book, such as for example the relations between France and Britain with the numerous jabs and hostile comments about the French made by the British, and various anecdotes, such as Bonnet remarking that in the event of war he would end up in the Seine - not because of the Germans, but when the working class rose up and threw him there, reflecting the fears of the Republic of property in front of popular revolt. Indeed, the book as a whole should be given credit for this: it is I feel one of the talents of the British in writing, that they have such excellent abilities to write portraits of historic individuals.

In the end, the book is a decent and detailed diplomatic history of the French in Europe in response to the Germans, albeit one which is narrow in its subject focus and which has had many decades pass since its writing. It backs up its assertions with plentiful facts, and stakes out a position which is slightly revisionist upon the topic of Bonnet, while simultaneously not excessively pressing on the envelope of the debate about French diplomatic history for the period. There is much which has to be done to compliment this book, but as a whole it makes for a useful addition to the library of diplomatic works focused on France, the lead up to the Second World War, and the Interwar.

- Amazon.com: France and the Coming of the Second World War, 1936-1939 (9780714630359): Anthony Adamth

Amazon.com: France and the Coming of the Second World War, 1936-1939 (9780714630359): Anthony Adamthwaite: Books

© 2019 Ryan C Thomas