German Orientalism in the Age of Empire Review

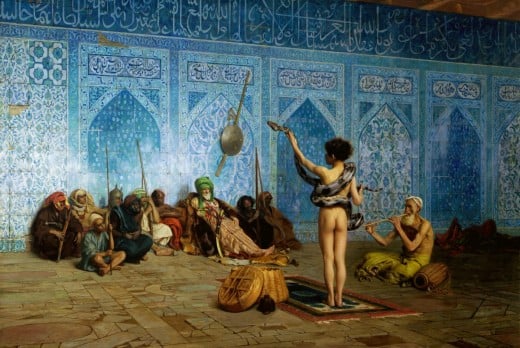

Orientalism, as in the academic discipline which studies the East and its cultures, languages, history, peoples, arts, and sciences, was once a relatively innocuous field, principally focusing on religious studies. Over time it developed an increasing study of secular affairs, and Western interest in the living, actual, Orient grew, as opposed to the dead one found in the pages of the Old and New Testament alone. But it wasn't until Edward Said published his book Orientalism in 1978 that our understanding of Orientalism as a discipline was hit by the equivalent of a hydrogen bomb, when Said redefined it as being responsible for establishing representations that enforced power structures of Western dominance over the Eastern world, turning them into subjects with depictions of them in the West that serve as covers for Western expansion - servile, backwards, un-dynamic, barbaric, unchanging, stagnant, and hence in need of Western dominance and control in order to reform and uplift them. Whether one necessarily degrees with Said's premise or not, the way which the field of Oriental Studies is itself put into historiography has been revolutionized, and any book about it has to, obligatorily, treat with Said's idea.

Suzanne L. Marchand's book German Orientalism in the Age of Empire: Religion, Race, and Scholarship, studies however, a nation which was unique among the great intellectual powers of the era, in not possessing extensive imperial interests in the East until very late in the 19th century. This was Germany, which Said put little attention into analyzing, yet which was an important nation for the study of the East, one of the three great nations in such regards, alongside Britain and France. Marchand does not directly dispute Said's claim, and indeed her introduction makes it clear that her book deals little with Said's premise itself directly, but the German Orientalism which she presents, one focused upon theological studies, ancient societies, textual analysis, and largely divorced from the ability to influence power and culturally marginalized in Germany compared to the classics, is one little in accordance with Said's view. Marchand's work provides for an incredibly detailed, and sophisticated study of German Orientalism, one which is not beholden to Said's ideas.

The lengthy introduction lays out the idea that we have been too concerned with binaries in the Occidental-Oriental relationship,and that we have done too much to assume a unified European discourse on the orient, when conversely the field was riven by its own internal debates, thus meaning that the author does not use Foucauldian discourse analysis, calling into question its universal application to the study of history. Thus it instead focuses on what it sees as a more nuanced view of Orientalism, one which perceives it as having greater traditional links to religious studies than simply being a secular project, and that the orientalists who it studies themselves were critical of their own society, even if they did often accept some basic divisions (such as a rational West and spiritualist East, but even there they sometimes saw the West as being its own fallen or decadent society from a time such as that of Christ). it ends with declaring what it wants to focus on in this study, such the various fields of orientalism, and its focus on the actual practice of Orientalism in Germany.

Chapter 1, Orientalism and the Longue Durée continues an overview of orientalism, seeing it as a phenomenon much associated with religious studies. This did start to change towards the second half of the 18th century with a secularization of the field, nationalism, and increased acceptance of non-Christian authors, part of dramatically increasing degrees of information on the East. Its different civilizations rose or declined in standing, China being very high in European estimations when falling dramatically, while India’s rose, and Persia first rose then declined; Jews, Arabs, and the Ottomans were drawn into European disputes as well. Particular prestige was attached in orientalism to age. Central Europe had a particular relationship to the East, due to its lack of colonial engagement and yet its direct military struggle with the Ottomans, and German scholars seemed to focus above all else upon the study of the East as a way to better comprehend the bible, touting their “objectivity” and with numerous liberals being the proponents of a tolerant and near-pluralistic view, condemning English colonialism.

Chapter 2, “Orientalists in a Philhellenic Age”, deals with the increasing domination of Hellenism in Germany during the early part of the 19th century, where Orientalists confronted a focus on the Greeks rather than their own interest in Eastern civilizations. They summoned up initially a wide range of defenses, including the believe in the indivisibility of Asia and Europe, of a project of cultural rebuilding of Germany through study of India, and of the profound mysteries of Asia and their influence on the Greeks, but were forced to retreat to positivistic, careful, and rational examination. At this point the chapter moves to the examination of the lives and experience of orientalists themselves, a dedicated bunch who continued their scholarly research despite, or perhaps because of, the complete absence of actual German colonial connections in the East.

Chapter 3, “The Lonely Orientalists”, provides a perspective of orientalism as a limited and vulnerable field, and of some of its components. One group were Jewish orientalists, who formed a group outside, but engaged with, Protestant orientalists, even if they failed to attain their own secular position in German academia, but which orientalism welcomed more than other fields. They focused on aspects that other Orientalists neglected, such as the Hellenistic period or Corboda. Others were Arabists, or Indologists. They had to deal with the emerging Aryan (Indo-European) and Semitic people divide, in some ways contributing to it themselves in an emerging specialization of knowledge which divided the world. Some went to as far as East Asia, but only a small amount compared to the Near and Middle East. Most of this deals with the examples of individuals, which is a recurrent source throughout the book, and these were a varied bunch, ranging from textual scholars, to adventurous voyagers, to gritty and unromatic travellers, to poets maintaining some of the spark of previous Romanticism, to a host of other categories. But asides from their biblical work, they were largely cut off from the ability to change society and to kindle interest: their defining feature was their weakness, not their dominance.

Chapter 4, “The Second Oriental Renaissance”, details the later part of the 19th century, when German orientalism finally began to blossom in size, even if it was always a relatively circumscribed discipline. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose: the religions and overlap with theology continued, but now a hugely increased amount of information and a willingness to privilege non-European sources over European ones could lead to new histories, such as that of Islam or a reworking of the history of ancient Israel which placed the Old Testament into a much later date and revisualized the role of faith for the ancient Jews. Assyriology came into the mainstream during this period, and interest in these states was also marked by a proto-Weberian type model of focus on the development of the state, and marked by their level of dynamicness in regards to their degree of individuality. Increasing academic projects in the field both continued to push it forwards in scholarly terms, but also decreased its accessibility to the public.

Chapter 5, “The Furor Orientalist” reflects a return to a more romanticist idea to pervade Orientalism, having finally achieved sophistication to advance upon the positivist model previously en vogue. Instead of philogism (the study of written texts), their interest was drawn to more speculative questions concerning the New Testament and Christianity in general, in what the East had contributed to them. They also started to engage in popularization of their works, driven by an expanding book and journal market. Universalist models of cultural development were rejected (where ideas develop organically in grounded cultures), in favor of a diffusion model where they spread from one to another, tremendously useful to revive the older Creuzer idea of a Western cultural debt to the Orient. In particular this was used for heralding Babylon as the source of much knowledge, by the Panbabylonism, in another attempt to dethrone both Greece and Israel from their centrality in the understanding of the ancient world.

Chapter 6, “Towards an Oriental Christianity”, returns to the ever present theological debate of orientalism, in this case principally applying the same concepts of diffusionism as previously done. Jewish debts to the Persians and other people of the ancient Middle East, as well as the potential that Jesus took his teachings from Buddha and other syncretic origins of the faith (making it into an Oriental religion), all due to diffusion and adoption, were hot theological topics. So too was the question of Saint Paul and whether he had created the historical person of Jesus. Interestingly, these could fit into the idea of a renovation of the faith in its removal of the elements of miracles to transform it to match the times, but it also shook traditional theology to the bones.

Chapter 7, “The Passions and the Races”, tracks how race evolved to become a major interest among the Orientalists, after initially being a marginal affair - existing, but never really of great note. Again, much of the interest in races, such as Aryan and Semitic races, was defined in terms of philosophy and religion, contrasting Aryan religious thought of a gentle god and immortality to a vengeful Semitic god and materialism. Interest in India was particularly pronounced, again for its spiritual values, Aryan and uninfected with Judaism. Defense of Semites was by contrast, confined to a narrow band of Jewish scholars.

Chapter 8, “Orientalism and Empire”, makes the case that German orientalists were themselves little involved or even affected excessively by the construction of the German empire, focusing on subjects not related to it (academia purposefully driving them to research on “useless” subjects), different regions, with wildly varying ideas, although they still did see some use of their ideas made in colonization. Germany established a school for Oriental languages and a colonial university, although the latter did not prove greatly successful. The Middle East was a subject for German orientalists on the modern world principally in relation to their research into Islam, often seeing it in negative terms as shackling the Middle East, or at most as a second rate version of Christianity which could be harnessed and used by the Europeans - although that was joined with integrating it as a religion into the scope of world history, an important development in intellectual history. East Asia had been largely previously neglected, but did grow to have a number of Sinologists and Japanologists, although the principal latter figure, Erwin Baelz, was himself opposed to the German colonial project in East Asia.

Chapter 9, “Interpreting Oriental Art”, relates how Oriental art was initially perceived purely in the decorative sense, and it wasn’t until near the end of the 19th century that it began to be seen as art at all, equivalent to Western classical-derived art, and to be displayed - although the display attempts of it failed themselves to achieve much popularity. A particular example presented is that of Persian rugs, which were a commodity which became a search for authenticity as well, as older, traditional methods of their production fell into disfavor, causing a scramble to buy them up. Art was not free of racial elements, such as Josef Strzygowski, who helped to racialize art history with his vaunting of “aryan” art, much of Iranian origin, as compared to “semitic” art. Europeans were engaged in a scramble for antiquities and art, and one of the most intriguing German examples was the Turfan Expedition to Central Asia which effectively looted a vast amount, literal tons, of art, manuscripts, and monuments, in the last decades of complete Western dominance in the semi-colonial nations.

Chapter 10, “Orientalism and Others” principally is devoted to the study of Orientalists during the First World War, although it really broadens itself into a much more expansive look into Ottoman-Turkish relations. It starts out by laying out the increasing relevance of the Orient in responding to European claims, and then Orientalist projects during the war to make themselves useful for the war effort, particularly in relationship to promoting the Turkish-German alliance intellectually. There were intense anxieties from various orientalists about the war being the end of Western civilization’s dominance and a revival of the East, but also simultaneous hopes expressed by others about the East’s capacity to rejuvenate a morally bankrupt West. As with other things, German Orientalism is hard to precisely pin down to a single discourse: both involvement in imperialism and participation in the construction of a more global and equal discourse on cultures and civilizations.

A final epilogue reviews the state of German orientalism since the Great War. During Weimar it experienced something of a reprieve, even if it was badly battered by the war itself, and for once it could claim greater connection to the spirit of the times than the classics, and new and innovative methods joined it. Weimar might have been, although it did have some inherent limitations, the development of a multicultural and anti-Eurocentric view as a defining feature of Orientalism: instead the Nazis arrived to power and purged the field, converting it to a purely racialized subject, and yet one which they also ultimately cared little about. German Orientalism’s venerable history and tradition, its leading role, largely came to an end and has not yet since recovered: it had joined the grave alongside the ancient civilizations that had for so long constituted its favored object of study.

The amount of research which Marchand has put into this work is breathtaking. It is difficult to describe the incredible breadth of this work, with such a huge number of individuals who are portrayed throughout the pages, or the impressive number of different ideologies and ways of thought. The latter is certainly one of the most inspiring, that Marchand could navigate with such ease through theological orientalism, positivism, romanticism, and a host of other schools of thought, each one being covered with amazing depth for how it was changed and configured. Vast quantities of detail and events pop up throughout the pages, describing actions, places, people, society, institutions, and concepts at great length.

It both displays the vast sweep of German orientalism in a detail which enables both a rich scholarly understanding while presenting the neophyte with a comprehensible narrative of the development of the thought and its relevance to society. The second point is in particularly highly importantly, for German Orientalism has a subtle and nuanced perspective on the relationship between society and orientalism and how the two impacted each other. Projects such as the study of India in the early 19th century as part of seeking a united spiritual body of Eastern wisdom to counter the advance of Kantian and Napoleonic rationality (in this case carried out by George Friedrich Creuzer) are ones which are explained in the context of society, as is how society received them and what the ultimate results were. The same can be said about theological concepts in the various debates over the Bible, or art history, or concepts of multiculturalism. This is tied intimately into what sort of orientalism existed: the book discusses the schools of thought which were developed and their generational differences with a steady and authoritative hand.

Such a display is backed up and humanized by describing the various personnages involved, displaying a dazzling variety of German orientalists from the 18th to early 20th century, with their biographies, type of work, and views. While inevitably these are short, window which is provided into the lives of those under study is invaluable. The sheer number can work against it admittedly, as can tend to overwhelm, and furthermore by reducing it to personal views the danger is that one gets a warped view of the subject study - often times Marchand takes pain to note that the individuals that she presents are a minority fraction, and one greatly different than that of the rest of the field, such as Erwin Baelz, a Japanologist profoundly different in his anti-colonial, anti-eurocentric, and actual residence in Japan and deep understanding of modern Japan, who varied very much from the profile of the standard orientalist. But these can be worked around, and certainly Marchand cannot be accused of neglecting the diversity of opinions which were at home with the German orientalists.

With continuing research and interest into Orientalism, the book is one that for those willing to take the time to read it, it can form a strong comeback to many of the arguments which Said proposed, by conversely demonstrating the detachment of the Orientalist scholars from forming modern representations about the East, their varied discourses, and the starting points of theology forming their interest, rather than the modern Middle East, India, or China. At the same time, it doesn’t necessarily dispute Said’s claims of an “othering” perspective of the East being formed, and it shows the way that some stereotypes and perspectives, particularly of the Semites, were formed. It neither reinforces nor destroys Said’s arguments, but complicates them, although admittedly generally in a way which seems to reduce their potency by showing the ways in which orientalism could be detached from formal colonial power structures.

Having a strong understanding of various elements at play in the history of German Orientalism and theological studies is important for fully understanding the importance of the book: in this I must confess to not having nearly the required amount, and thus for example, the discussion on theological developments is nearly entirely lost upon me in its deeper details. But while the subject is a complex one, the author’s pen is not intimidating, and she does enable even the neophyte like me to understand the concepts with which she is working. Similarly, the text is liberally spotted with German words, which although generally not per se necessary to understand the text, do show that some comprehension of the language is useful to its full understanding.

Furthermore there are shortcomings which are inherent. To start with, the volume is devoted purely to academic orientalism, and even there principally of the text-bound variety. There is very little of popular interest in the orient either from outside of the academic spectrum, or how academics engaged with this. As noted previously, some attention is placed upon what the broader projects were for Orientalists in reference to society, such as the idea of reconstructing European culture upon the example of a single, unified whole as presented by India, to resolve the question which had been important in Europe of a division between the sources of European heritage - Christianity or the Classics. So too there is some theological discussion and its relation to the public. But these are all very top-oriented works which come from above to descend to the people. Perhaps this shouldn’t be called a shortcoming, instead rather a specialization, but it is something to be aware of before reading it.

It is admittedly, extremely long, and although for the neophyte it is understandable - I consider myself to be one in relation to the field of German cultural studies, although I do know more about orientalism as a theory and the debate occasioned concerning it by Said so perhaps for others it would be more difficult to read - it is also something which is truly best as a reference book. Otherwise, keeping track of the huge list of individuals portrayed throughout would be both impossible, but also probably useless - while many of them are interest, the dozens, perhaps scores, of personnages can tend to blend into each other. One is best reading the book if one is deeply interested in the field of German orientalism. There is so much information available that it is difficult to absorb otherwise, although it is, as noted, possible for an amateur like myself to read it and comprehend what it is saying. In particular, one group which can find it intriguing is one which one might not normally assign to the subject of Orientalism: that of theologists, since the book does such a good job of showing how theology interacted with Orientalism. Other than those in the field itself of orientalism, and theologists, and those studying German history, it is also a useful intellectual history. While long and hard to read, its sheer level of detail and its wide net makes it a fascinating work for anybody willing to dedicate the time to working through it.

© 2018 Ryan Thomas