Greek Prostitutes in the Ancient Mediterranean, 800 BCE–200 CE Review

Greek Prostitutes in the Ancient Mediterranean 800 BCE-200 is a collection of essays edited by Allison Glazebrook and devoted to the subject of the history of the oldest profession in the Greek world. It offers multiple snapshots, rather than a cohesive history of the subject, not by failure but rather due to intent. Studying such a subject is important to understand social, cultural, and sexual life throughout history, and to better enable us to grasp our own society: it shows that throughout history and places people have shared both commonalities and differences between our view of sexuality and their own. Greece, as this book notes, certainly had a wide variety of differences, in how sexuality was conceived and how it fit into society. As noted later on there are certain inaccuracies to this title, but the book does embrace a wide range of material on the field which makes it useful for scholars, although for the general public it might be a read of lesser utility. The book includes a chapter written by the author of another bookon Greek pro stitution, but is quite a different book.

The introduction lays out the relevance for the work, as it is important for both gender and sexual history and broader history in general. There has been too much focus on the upper Greek escorts, the “heteirais”, and insufficient upon the rest of Greek pliers of the oldest profession, their representations, and relationship to society. Thus the book professes to wish to try to correct this

Chapter 1, “The Traffic in Women: From Homer to Hipponax, from War to Commerce” by Madeleine M. Henry notes that the principal objective of Homerian war was to secure booty, not land, and an integral part of this was the enslavement and capture of women. War was in a sense indistinguishable from raiding, and the capture of slaves was an integral part of inter and intra-Greek commerce. Raiding formed a vital way to gain access to women, and it was not until later, such as the 6th century BC in Athens, that alternatives such as a state regulated brothel system (established in legend by Solon who established important laws for Athens - whether true or not it is clear that there was developments of prostitution during these centuries) were developed that provided an alternative.

Allison Glazebrook writes chapter 2, “Porneion: Prostitution in Athenian Civic Space” that the oldest profession was divided into an array of different labels for both its act and for the houses of ill repute where it took place in. The Greeks did not always have dedicated brothel architecture like the Romans, and instead their function could be identified by the people working there: thus these establishments could be intermixed in tenements. There may have been some dedicated architecture for this type but archaeology is still not capable of confirming this. One potential building is Building Z, which is elaborated upon in the text, as one of the few examples of a large building which might have been just such a house. But even this building had other functions, such as textile production, and as a tavern, indicating that prostitution spaces were often shared spaces. The customers, argue the author, were not simply the poor but rather a broad social spectrum, visiting houses of ill repute that were diverse in their accommodations and quality, and often hardly the dismal image portrayed.

Chapter 3 “Bringing the Outside In: Andron as Brothel and the Symposium’s Civic Sexuality” by Sean Corner discusses the role of the symposium, a gathering of citizens for a social meeting, in the “andron” (a part of a Greek house, used for entertaining and greeting) as being a reflection of a sexuality at odds with the domestic sexuality found normally within a citizen’s house. Wives were of course associated with domesticity, and while Greek husbands did not have to be faithful, the house was normally off limits to his forays. The symposium represented a unique time when heteirais were allowed access to the home, forming a distinction from the domesticity of relations for producing children with one’s wife to that of enjoyment and condoned private sexuality of the male citizen in their power over an available woman, forming a key element of anti-domestic sexuality that was distinct from either a wife or a courtesan and instead reflected the prerogative of the private citizen who was free to act to his own desire.

Continuing in the 4th chapter “Woman + Wine = Worker in Classical Athens?” by Clare Kelly Blazeby, there is a discussion of whether the portrayal of wine with women inherently means that these women are pliers of the oldest profession or of dubious moral character, as has been previously assumed. Conversely, women in ancient Greece certainly indulged in drinking (including male stereotypes about that being produced), as was the case in the broader world of the time, and while symposiums might have been male-exclusive, there were plenty of other occasions where drinking, including mixed drinking, would have been acceptable. Our view has thus been excessively influenced by the Symposium ideal.

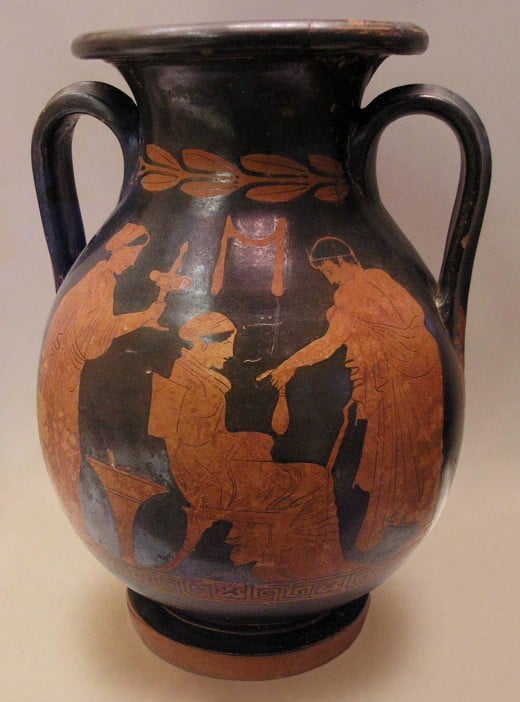

Chapter 5 “Embodying Sympotic Pleasure A Visual Pun on the Body of an Auletris” by Helene A. Coccagna continues on in the subject of discussing artistic depictions, in this case in a Greek pottery piece which shows a woman surmounting an amphora and entering it inside her. Coccagna claims that the trope had been used elsewhere, such as with satyrs, and was a Greek stereotype of women as lustful creatures (part of a discussion on the Greek view of creatures driven by their animalistic urges, often represented by the stomach), that it represented the pleasure of both wine and women at Greek symposiums, and that the vase had connections to anatomical functions such as the stomach.

Chapter 6, “Sex for Sale? Interpreting Erotica in the Havana Collection” by Nancy Sorkin Rabinowitz discusses a variety of different classical scenes and the ambiguity found in determining their status as scenes of prostitution and in the relationships between men and women within.

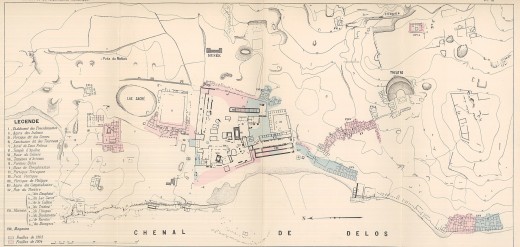

Chapter 7, “The Brothels at Delos The Evidence for Prostitution in the Maritime World” by T. Davina Mcclain and Nicholas K. Rauh covers Delos and a variety of different archeological elements, such as frescoes and a building with a variety of small chambers attached to a men's club, utilized as evidence for prostitution.

Chapter 8, “Ballio’s Brothel, Phoenicium’s Letter, and the Literary Education of Greco-Roman Prostitutes: The Evidence of Plautus’s Pseudolus” by Judith P. Hallett discusses a (Roman era) play where a pliers of the oldest profession named Phoenicium wrote a letter, used by the author as part of a discussion on education and training for the workers of the oldest profession.

Chapter 9 “ Prostitutes, Pimps, and Political Conspiracies during the Late Roman Republic” by Nicholas K. Rauh deals with the political chaos of the 1st century BC, where a wide range of different factions were hostile to the oligarchical Roman republic. A claim from the members of this oligarchy was that their opponents were united in a social cross section stemming from houses of ill repute and taverns, engaging in socially questionable acts and encapsulated fears over alien subversion of the political system, a fear often expressed in conspiracy theory type views. This helped to undercut and undermine their opposition.

Published by the same author of Prostitution in Ancient Greece, Chapter 10, “The Terminology of Prostitution in the Ancient Greek World” by Konstantinos K. Kapparis examines how the Greeks referred to prostitution and what sort of words existed for it. The Greeks produced a stunning number, up to 200 (10 times our own allotment), indicating different levels ranging from common pliers of the oldest profession to courtesans, and euphemisms, as well as names for houses of ill repute (with “workshop” being the most common). Their terms for male pliers of the oldest profession took on an increasingly moralistic tone as the millennium before Christ came to a close, replacing previously light-hearted appellations. Eunuchs too received their fair share of names, perhaps because of their peculiar gender status. The chapter ends with an extensive list of all of the terms the Greeks used.

The conclusion, “Greek Brothels and More” by Thomas A. J. Mcginn conducts a summary of the articles which are presented in the book, and lays out that their value lies in analyzing the degree of marginalization or legitimization of prostitution in the ancient Greek world. The limits of available information always circumscribe our understanding, but he hopes that the book enables us to form a better picture of the practice. A references list, contributors list, index, and suggestion of other books on the classics follows.

Review

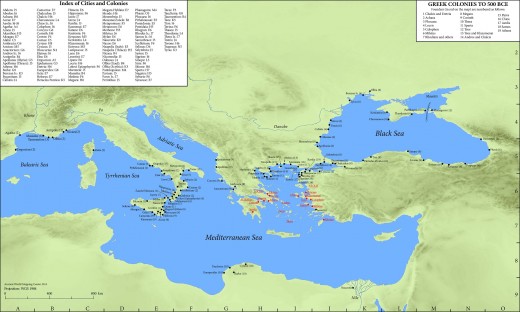

To start with, this book’s title and its contents diverge. The book concentrates not on the 800 to 200 AD period, but principally upon 600 BC to about the first century before Christ. The only section which can be interpreted from earlier is Homer, who was admittedly from the 8th century BC, but who was after all, involved principally in representing events from some four to five centuries earlier. It also goes beyond Greece itself, to Rome, and yet conversely within the Greece world, while it does move away from Athens somewhat (specifically with its chapter on Delos) it continues to focus principally upon the cultural capital of the ancient Greek world as the standard for the rest of Greece. I must personally admit my disappointment to some extent, as I thought that the book with its focus on the ancient Mediterranean, would place more attention on a broader selection of sites, and upon transnational connections, spawning borders, societies, and forming networks across the Mediterranean - something which has become the increasing focus of many modern such works. Similarly there are chapters that don’t deal with prostitution at all: prostitution is an exchange of resources, typically money, in exchange for sexual acts. Thus although covering enslavement may be intriguing, is it really prostitution….? Similarly the extensive literary analysis of a woman having intercourse with an amphora only vaguely relates to the subject. But my disappointment in such regards does not render a book bad, for there are other attributes which the volume does have. Do they make up for this unfaithful following of the title?

There are some quite good sections in the book. Relating the distribution and zoning of brothels in Greece is fascinating. So is the discussion of sexuality in symposiums which is a very interesting demonstration of how sexuality, domesticity, and citizenship intersected. And as providing for an idea of changing sexuality and how pliers of the oldest profession are portrayed, as well as a reference, the chapter on terms and portrayals of pliers of the oldest profession in Ancient Greece does much to enlighten one’s understanding of the subject and provide for scholarly material.

Not all chapters are as intriguing. For example, the very first chapter, declaring that raiding focused heavily on the capture of women as slaves is almost tautological: women were a valuable prize for raiding. This should come as a shock to nobody: women have almost always been a prize for raiding expeditions throughout history, and to anybody with a basic knowledge of the Iliad and the Trojan War, the capture of Helen of Troy is well known. Perhaps it is a distinction between the classics as a discipline and other sections of history, in that the focus is on presenting elements of the classical tales such as the Iliad in a new light, even if the new historical information gained is not great. And the chapter on Phoenicium’s Letter is only extremely vaguely related to prostitution, and the author seems to find it difficult to relate it to anything else except in the threadbare links of potential education among pliers of the oldest profession. It is much more a literary work analysis. Women + Wine to analyze drinking patterns may raise an interesting point, but it also has a stunningly short reference section and is rather speculative.

Sometimes the books run into direct contrast, such as for example on symposiums - Athenian banquet events - which Konstantinos K. Kapparis' book sees informal and less classist and sexist attitudes in, while s in the Ancient Mediterranean regards them, as being aristocratic exclusivity. For different interpretations it is intriguing.

This book could have done its subject better, and there are chapters which to me seem unnecessary or flawed. But it is broad enough in its range of information and changes from the previously stilted and upper class perspective which was common in other volumes on the subject. For those interested in Ancient Greece, sexuality in Ancient Greece, the history of the world's oldest profession, and literary and artistic analysis of vase art and Graeco-Roman literature, it makes a useful scholarly tome. Its just a shame because it could have been more in my opinion.

© 2018 Ryan Thomas