Information Brushed Against Information

INTRODUCTION

"When information is brushed against information, the results are startling and effective." Marshall McLuhan.

Woody Allen’s Bananas begins with the televised assassination of a Central American president, a scene that could have been reminiscent of a tragically beautiful Gabriel Garcia Marquez novel or the stark realism of the Zapruder film of JFK’s assassination, but the director immediately throws a curveball by inserting sportscasters into the scene, including a hilariously invasive Howard Cossell, who gives a play-by-play of the events as if it were a boxing match on the Wide World of Sports. By then, Allen had already made a wacky, original film by redubbing a Japanese spy film into What’s Up, Tiger Lily?, but what possessed him to juxtapose two seemingly incongruous media, the film itself, which depicts an assassination, with a television sports report? It’s an absolutely brilliant bit of filmmaking

Ever since I saw that scene, and several other similar scenes in various Woody Allen films—notably a number of scenes from Annie Hall and the entire premise of Crimes and Misdemeanors—I’ve been fascinated with the use of multiple media types within a single work, a branch of art without a single name; “multimedia,” “mixed media,” and “media hybrids” come to mind, but perhaps it is best that it is not pinned down. It isn’t my intention to set rules or guidelines, but rather to explore the various ways in which forms of media can be combined and especially the effect that such a combination/ juxtaposition can have on the audience. Nevertheless, for clarity if nothing else, I will be using the term “intermedia,” which I define vaguely as the combination of two or more media in the creation of a singular work. It’s a term I’m borrowing from the Fluxus artist collective, the loose group of artists that partly “inspired” John Barth to write his famous metafiction manifesto, “The Literature of Exhaustion.”

I should point out that I will be using the term “media” rather liberally; for instance, performance art isn’t technically a medium, with some extreme examples being wholly unrecordable and ephemeral, lost forever to time. On the other hand, I will also be including the various genres of a medium as if they were each a distinct medium in their own right. For instance, in the print medium, there are typically considered to be four genre: fiction, drama (printed plays and screenplays), poetry, and non-fiction, creative or otherwise. Despite being the same medium—print/text—we as readers approach, view and consume each genre as differently as we would if we were walking through an art museum, circling around the marble statues to see every angle, stepping closer to the impressionist paintings to see the brush strokes, and wondering how many shots it took to take that one incredible photograph.

Do you read a poem several times before moving on, and out loud? Even if you do, I bet you don’t do that for each chapter of a novel, do you? Why is that? When you read a play, don’t you imagine how it would look and sound on stage at your favorite theatre? I know I do. When you read a piece of creative non-fiction, the aesthetics of fiction rarely concern you. You don’t worry about plausibility or dramatic structure or symbolism, or how it fits into the current modes of literature; you—hopefully—wonder about the author’s welfare after having endured the events of the book.

This audience response is perhaps the single most important aspect of intermedia. An audience often has preconceived notions and prejudices about each medium (“Opera sucks,” “Why are there so many words? Why can’t there be more pictures?”), and as such, they may have a different reaction to the exact same information simply because of the medium chosen. There is something powerful, and occasionally blinding, about these preconceptions. I know some people who refuse to read fiction, but will pick up and read anything based on a true story; on the other hand, there are those, especially in academia, who reject all forms of creative non-fiction as navel gazing at best, lurid self-promotion at worst. A sharp writer—or an unethical writer—can use this to their advantage or their disadvantage. For instance, let’s say that James Frey had published his book, A Million Little Pieces, as he’d originally intended—as fiction. It’s hard to imagine the same kind of controversy erupting from the public learning that—GASP!—the author had filled his fiction with bits and pieces of his life, but just that slight difference, in releasing it as a memoir, created inescapable differences in expectations and aesthetics that caused many to judge the same exact words on the page much more harshly.

GALLERY 1

Click thumbnail to view full-size

A BRIEF HISTORY OF INTERMEDIA

The concept of combining different media into a single work has been around for centuries. Without going back into ancient and prehistoric times (one could argue that music (sound) and dance (movement/performance) were likely the first combination of art forms, but did dance begat music, or was it vice versa?), we can point to the history of books for early examples. The illuminated manuscripts, such as the Book of Kells—which was made into an excellent animated a few years ago—were hand-copied texts with beautiful script, decorated borders, and fine illustrations. Taoist scrolls combined fluid paintings of landscapes or animals with poetry.

After the invention of the printing press, many books still incorporated illustrations, if only in the form of a frontispiece. Less obvious examples include fictional works that imitated non-fiction forms (travel writing, epistles, newspaper articles, diaries, etc.)—Gulliver’s Travels by Swift, Frankenstein by Shelley, and the novels of Samuel Richardson—as well as books that combined poetry, prose and/or drama, either in the form of epic poetry (The Odyssey, Paradise Lost) or by including poetry/prose/drama sections, sometimes on the same page (I am currently without a substantial part of my book collection, and I can only give modern examples for now: Pale Fire by Nabokov, Naked Came the Stranger by “Penelope Ashe,” and the three books by Woody Allen, Side Effects, Getting Even, and Without Feathers).

One of the first and most influential academics to study media and its effects on art and audience was Marshall McLuhan. In the chapter “Hybrid Energy” from his book Understanding Media, he refers to works of combined media as “media hybrids” (59). Specifically, he discusses the “crossings or hybridization of the media,” especially in such inherently multimedia art forms as film and television, as being an agent of “great new force and energy” in not only art and culture but in society as well (57). Media, which he metaphorically defines as the “extensions of man,” are “make happen” agents, but not “make aware” agents (57). By this, he means that the media themselves are an action, separate and independent from the intentions, ideas, feelings, aesthetics, etc. that the artists are trying to make the audience aware of—in other words, they have certain effects on the audience regardless of intention.

McLuhan also posits that the interactions of media “[spawn] new progeny.” The theory is that when “two seemingly disparate elements are imaginatively poised, put into apposition in new and unique ways, startling discoveries often result.” We already have some commonplace forms of intermedia, which through time and familiarity have become their own distinct medium: illustrated books (including comic strips and comic books), operas and musicals, movies and television programs, animation, and magazines. They were all born out of a fusion of pre-existing media and, almost always, the invention of some new technology, as McLuhan points out in his works. Media evolves with technological advances; in support of this, McLuhan quotes Sergei Eisenstein’s Notes of a Film Director, in which the famed silent director writes, “As the silent film cried out for sound, so does the sound film cry out for color” (57). The mixture of media therefore is a step in the evolutionary process of the current spectrum of media.

In the mid-Sixties, the Fluxus artist collective expanded on McLuhan’s ideas and made what they called “intermedia” their mission, believing that art’s “separation into rigid categories” was a symptom of class divisions and social problems and, as such, something to struggle against (Higgins, “Synesthesia”). The collective— George Maciunas, Dick Higgins, George Brecht, La Monte Young, among others—saw their art as descending from “dada, futurism and surrealism,” and staged “happenings” that often included performance arts, visual arts, and literature as a way to include the audience in the work (Higgins). One such example was Dick Higgin’s drama, Stacked Deck, which was written “as if time and sequence could be utterly suspended, not by ignoring them (which would simply be illogical) but by systematically replacing them as structural elements with change” (Higgins). This was accomplished with use of colored light cues, so that every night the order of the scenes could be altered to suit the reaction of the audience (Higgins). Robert Filliou’s Ample Food for Thought, according to John Barth, consisted of “a box full of postcards on which are inscribed ‘apparently meaningless questions’ to be mailed to whomever the purchaser judges them suited for” (Friday 66, 65).

Later that decade, John Barth, in his essay “The Literature of Exhaustion,” laid the groundwork for what would later be called “metafiction” by comparing the literature-within-literature works of Jorge Luis Borges with the output of the “technically up-to-date non-artists” Fluxus collective. In contrast to his condemnation of the Fluxus collective, Barth celebrates Borges’ story, “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote,” a story that, like Gulliver’s Travels or Frankenstein, is written in a mock non-fiction form; in this case, it is written as a fictional essay comparing Cervantes’ famed novel to that of the fictional Menard’s word-for-word copy of Don Quixote (72-73). The crux of the story is that the essayist-narrator constantly faults the original, older work as being old-fashioned, while praising the newer copy for its ingenuity and originality (72-73). Barth’s own work has similar characteristics; Chimera is a re-imagining of three ancient tales, including a retelling of the Bellerophon myth in prose, letters, interviews, and diagrams. Through its use of various print media in a fictional setting, metafiction, then, becomes fiction commenting on fiction, or fiction that explores the boundaries of the medium.

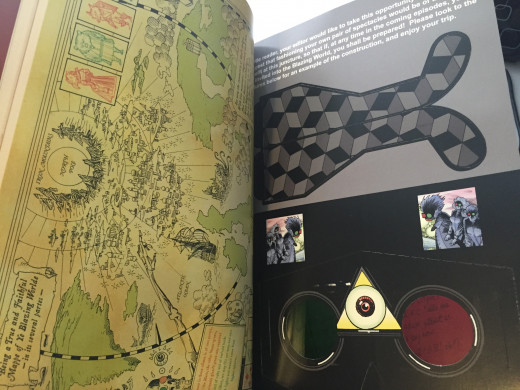

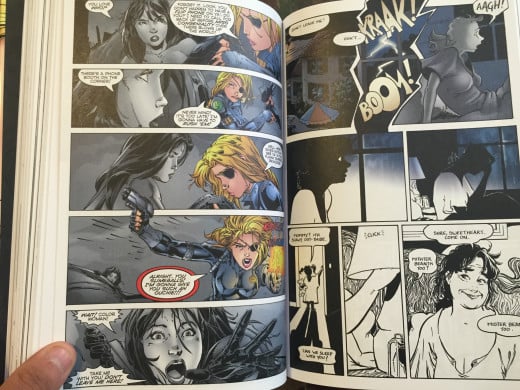

In the decades since, intermedia has been used in a variety of ways and extents, from the (fake) family pictures (Carol Shields’ The Stone Diaries) to the inclusion of complete, though sometimes completely imagined, books-within-books (Markus Zuzak’s The Book Thief and A Tale of One Bad Rat by Bryan Talbot). More complex examples of intermedia include “found” novels, such as Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves, in which the reader is presented a collection of writings, photographs, and ephemera to sift through, most pertaining to an unseen and likely fake short film that purportedly documents a supernatural event. Others have shown the literature of an alternate timeline or a completely different world; Alan Moore does this in Watchmen, showing us a world that could have been if costumed heroes and super humans were documented fact, partly through the literature of that world—the pirate comics that rise up in place of superheroes, chapters of a costumed hero’s memoir, political writing from both sides of the aisle, rap sheets, scientific papers, and more. As a comic book nerd, I like to call this version of intermedia “geek completism,” which is just the desire to collect and compile all the information having to do with a subject. While a technically impossible endeavor, John Barth proposed metafiction (or “the literature of exhaustion”) as a similar endeavor—as the implication of completeness, finality,

What are the effects of all of these disparate elements on the audience—do they question what’s real and imaginary? Do they open their minds to see that the impossible is possible, as in the case of the house that is demonstrably larger on the inside than the outside? Maybe we’ll see.

GALLERY 2

Click thumbnail to view full-size

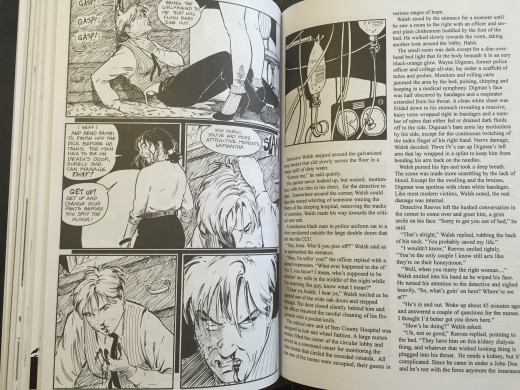

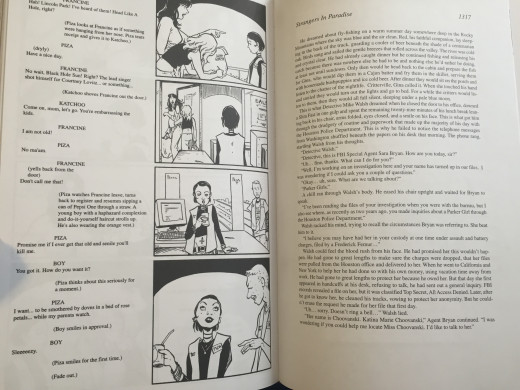

ELEMENTS OF PRINTED INTERMEDIA

What sets intermedia apart from traditional novels, short story collections, or poetry collections are elements that force the reader to view the work outside of their usual aesthetic and narrative mindsets. These elements are nothing new, and in many cases could be considered “found,” even when they are invented by the author. Besides prose and poetry, an intermedia book might include other forms of pure, printed media (media presented in its intended form): newspaper and magazine articles, encyclopedia entries, dictionary pages, photographs, drawings, illustrations, comic strips, and comic book pages. This can also include ephemera such as diary entries, personal photographs, tracts and leaflets, advertisements, birth certificates, court orders, postcards, etc. Even excerpted, these media forms lose little-to-nothing in book form, and have the added benefit of a preconceived context to guide the reader. An encyclopedia entry will have different expectations for a reader than a diary entry, the former being absolutely objective (in theory) and expansive in its knowledge, while the latter is generally very subjective and limited to the diarist’s range of knowledge and, most importantly, experiences.

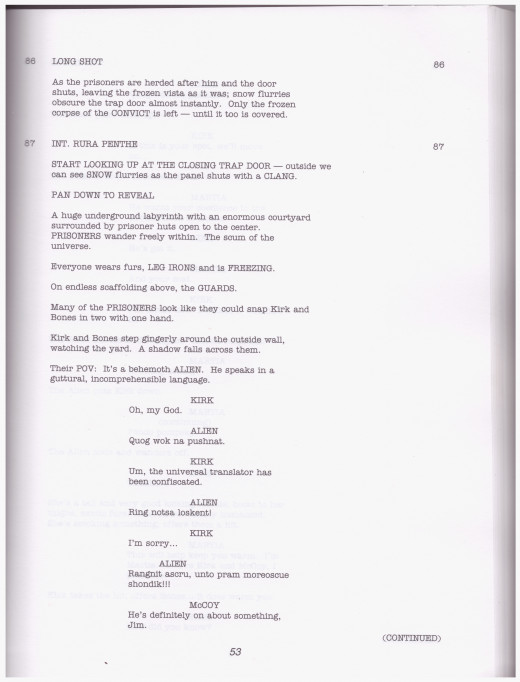

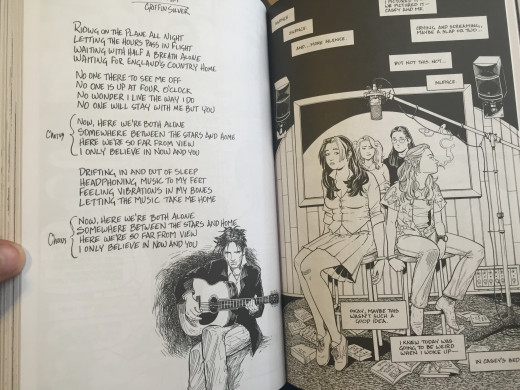

An intermedia book can also include representations of non-print media, such as works meant to be performed and/or viewed by an audience (printed plays, screenplays, opera subtitles, song lyrics, sheet music, animation cels, etc.). Traditionally non-art media can be included as well, such as TV news transcripts, radio transcripts, message board posts, web site home pages, TV commercials, and the like. Each of these media types brings with it certain limitations when converted to print media. The most obvious is the loss of the performance itself: the presence of the actors and/or musicians, their interpretations of the work, the sights and sounds and smells of a theater or music hall, the motion. A printing of a painting can rarely capture the size of the actual work, let alone the texture of the brushstrokes, so noticeable on the real thing hanging in the museum. Even poetry can seem less interesting on the page than when read as intended by the poet.

So why do it? Sometimes the limitations themselves work to the author’s advantage. As Marshall McLuhan wrote:

“Media, by altering the environment, evoke in us unique ratios of sense perceptions. The extension of any one sense alters the way we think and act—the way we perceive the world. When these ratios change, men change”

(Massage, 41).

Fiction and poetry, for instance, each have different objectives. Fiction, according to Laurence Perrine, “takes us, through the imagination, deeper into the real world: it enables us to understand our troubles” (Literature, 4). X.J. Kennedy wrote, “What we expect from fiction is a sense of how people act, not an authentic chronicle of how, at some past time, a few people acted” (Fiction, 3). Between these two beliefs, we can see, reductively, that fiction involves characters, trouble (conflict), and insight, all of which pertain, even in the most far-out science-fiction fantasy, to our real world in some way.

In his poem, “Ars Poetica,” Archibald McLeish wrote that “a poem should not mean but be” (Perrine, Literature 650). Although poetry in the western hemisphere began as narratives set to verse (Barnet, Introduction, 333), presumably for easier memorization in the centuries before the printing press, modern poetry has moved past the need for story, plot or characters, and in fact some poems function purely as abstract language. According to Perrine, poetry might provisionally be defined as “a kind of language that says more and says it more intensely than does ordinary language” (Literature, 517). Poetry, therefore, is much more compact than fiction, often just centering on a single moment of time and trying to recreate the experience in words, “to widen and sharpen our contacts with experience.”

What one gains in a work that combines both is a way for the author, through the alternation of the two genre/media, to jolt the reader into changing his perception and focusing on a different aspect of the work for a short time. Also, it is a way for the author to use the devices of one medium that would go unnoticed in another. Poetic devices, such as sound devices like rhyme, alliteration, assonance, consonance and onomatopoeia are rarely noticed when buried in fiction, except by the most perceptive readers. On the other hand, a poet might write a poem without line-breaks to imitate the look of prose, which could be a tip-off for the readers to take it in through a prose aesthetic.

Stretching this concept out little by little from the central putty ball of traditional literature, we come to plays and screenplays, both dramatic forms. According to Perrine, while drama is similar to fiction and can have elements of poetry, it “has one characteristic peculiar to itself. It is written primarily to be performed, not read” (Literature, 837). So what happens when you remove that important element and let the pages speak for themselves? What you have are two similar-looking, though profoundly different, ways of portraying action and dialogue. Sandra Scofield delineates the two forms this way: “In a film, words are the least important element in a scene. In a play, words are probably more important” (Scene, 13). Professor and screenwriter Paul Lucey concurs, pointing out that when filmmakers adapt stage plays for the screen, they must open them up “so they have more visual content and so they do no bury the script in dialogue” (Story Sense, 15). This is even more evident when comparing screenplay format with that of a stage play. Screen time is a very important factor in a screenplay. Because the average movie is between 90 and 120 minutes, the average screenplay is limited to that many pages. Whereas a playwright might be expected to keep the characters talking, a screenwriter is expected to keep the action moving.

Now, compare these drama media to those of literature. Drama is limited by the demand of the media to an objective, outsider view. Unlike literature, in which the writers can convince the readers that they are looking at events through another’s eyes, screenwriters and playwrights can only write what will be presented to the audience, either through aural, visual, or, rarely, tactile sensations. The audience members are invisible witnesses to the events of the play or movie. When viewed in its printed form, however, the audience is removed, just as the performers. What remains are the pure facts of the scene, unobtruded by even an omniscient narrator.

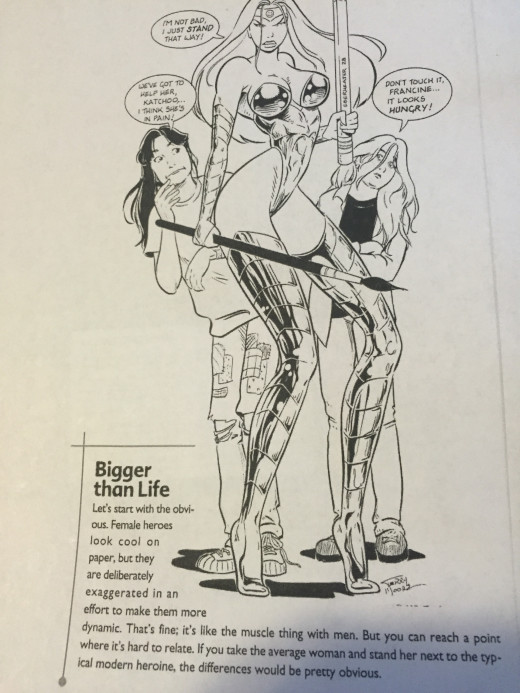

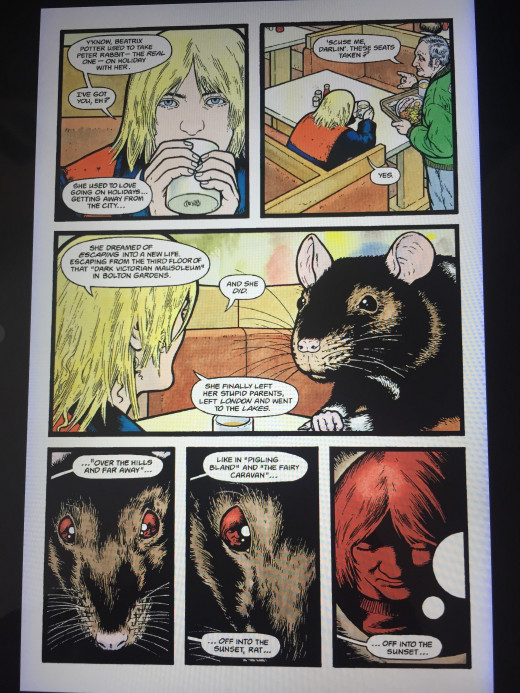

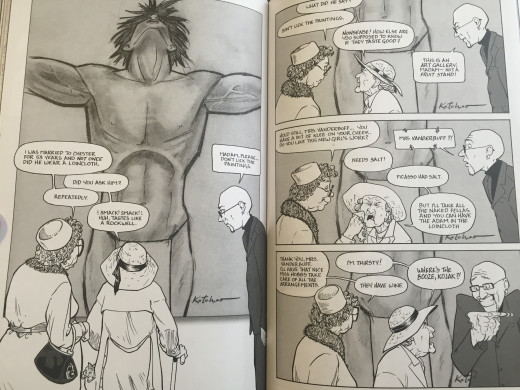

From drama we stretch out into the visual arts, works that, according to the old adage about pictures, are worth a thousand words, yet cannot be replicated in prose or poetry. With words alone, the senses can be stimulated by the reader’s imaginings of the words of the author, but what writer could adequately describe the anthropomorphic rabbit that is Bugs Bunny or the stylistically ugly characters in a Robert Crumb comic? How can a writer describe the look of an alien species without resorting to comparing it to an existing creature? Or the heroine’s reflection in her imaginary rates eye in Bryan Talbot’s A Tale of One Bad Rat? Pictures, photographs, sculptures, comics, drawings—they all present the world to the audience through visual means, though they do not necessarily represent reality. In the movie Harvey, Elwood’s sister says that the difference between “a fine oil painting, and a mechanical thing, like a photograph,” is that the photograph “shows only the reality,” while “the painting shows not only the reality, but the dream behind it.” The visual arts allow the artist’s imagination to come through, without having to rely on the interpretation of an audience.

Music is an art form that, even more today than a hundred years ago, has uniquely mercurial properties when it comes to media. There is no other art form that is disseminated to the public in so many passive and kinetic ways. Live performance, radio, recorded media (CDs, 8tracks, records, MP3s), soundtracks to movies, even Muzak in departments stores and elevators—music is all around us.

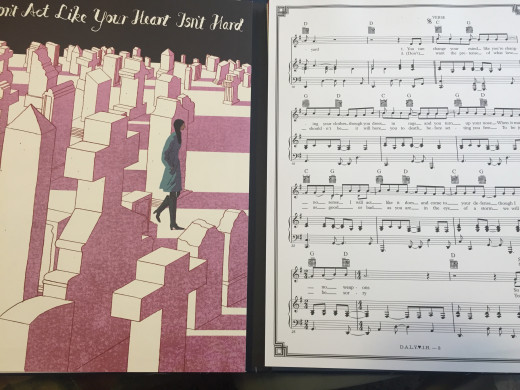

In print form, music comes as sheet music, lyric sheets, tablature, liner notes, and even old player piano rolls—essentially long rolled up sheets of paper with holes, a medium that translates itself from printed form to aural form directly through an instrument (though a very specific, purpose-built instrument) instead of relying on needles and amps and speakers and lasers. On top of that, recorded music often has packaging that goes beyond a printed representation of the music to include cover art, portraits of the musicians, thank yous, and historical information. Or, if you’re Led Zeppelin, Rare Earth, or Three Dog Night, you might have album covers with customizable windows, a flap to imitate a denim sack, or a set of oversized trading cards. Excess and novelty aside, an R. Crumb drawing of a bra-less, yellow-dress wearing Janis Joplin, as on the cover of Cheap Thrills, goes a long way towards suggesting not only a reason to buy the album but a context in which to listen to it.

I want to elaborate a bit on something mentioned in the brief summary of metafiction, which was that one of the forms that metafiction and intermedia can take is that of literature and media within the world of the characters, whether written by the characters or influencing them. These elements could be called “found” literature, or in some cases, ephemera. Interspersed throughout Ellen Wittlinger’s young adult novel, Hard Love, are letters, poems, and pages from “zines”—homemade, often-painfully autobiographical magazines that the characters create and distribute for free at music stores and on the street. In Bryan Talbot’s graphic novel, The Tale of One Bad Rat, Helen, the main character, imagines “finding” a lost Beatrix Potter book, which is printed in its entirety in the middle of the last chapter, although in the “reality” of the graphic novel, it turns out to be a story that Helen has envisioned all at once as an allegory of her hard life. In Last Day in Vietnam: A Memory, comic book legend Will Eisner includes sepia-toned photographs of Vietnam alongside his nonfictional, almost-journalistic comics, which were culled from his years in the military and as a civilian contractor.

GALLERY 3

Click thumbnail to view full-size

IN FUTURE POSTS

While I plan on examining a few movies (the works of Woody Allen, Quentin Tarantino, and Paul Verhoeven come to mind), most of the works I will examine will be self-contained books of some kind, though some might fit that definition only loosely. Most will have a preponderance of either literary prose (fictional or CNF) or poetry; others will feature comic art. These may include any number of the following, and others as I discover them:

The books of Woody Allen

Annie Hall/Zelig/Crimes and Misdemeanors by Woody Allen

Kill Bill by Quentin Tarantino

Grindhouse by Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriquez

Need More Love by Aline Crumb

Diary of Teenage Girl by Phoebe Gloeckner

Storyteller by Leslie Marmon Silko

Watchmen by Terry Moore

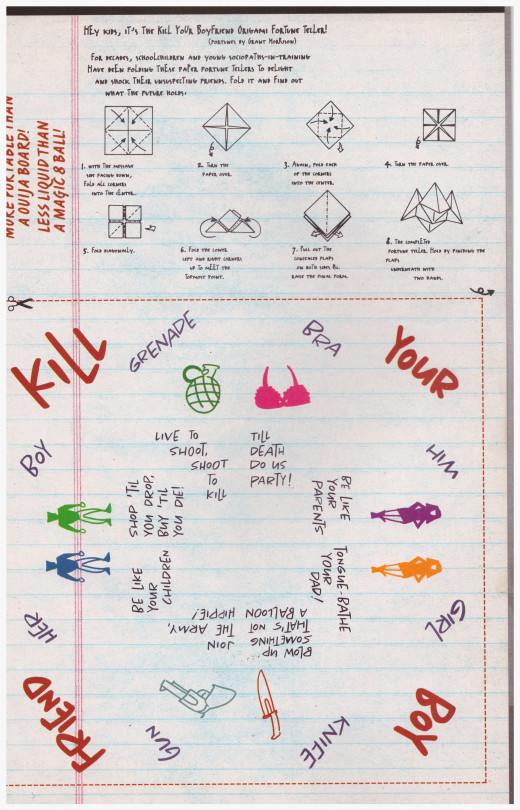

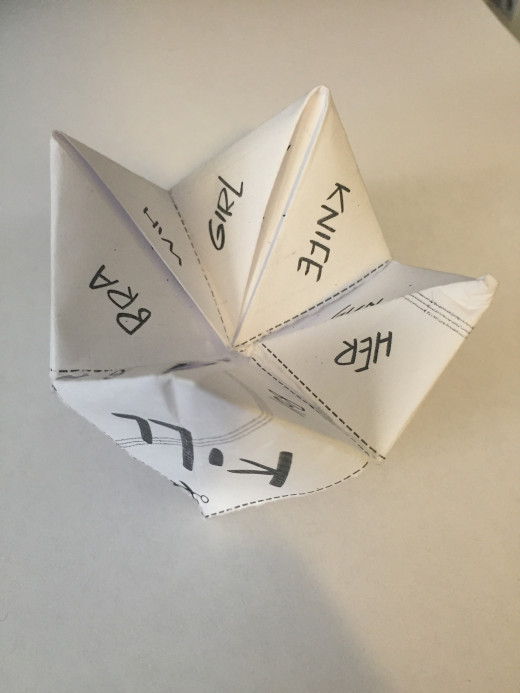

Kill Your Boyfriend (with other short comics)

League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier

Scott Pilgrim by Bryan Lee O'Malley

Perfect Blue by Satoshi Kon

Jin-Roh by Hiroyuki Okiura

The Elephant Vanishes by Haruki Murakami

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, along with other early fiction that took the form of non-fiction

The Rainbow Box, Joseph Pintauro

Video games in general, especially interactive fiction

Song Reader by Beck

Strangers in Paradise by Terry Moore

October Light by John Gardner

Robocop/Starship Troopers by Paul Verhoeven

“Found Footage” horror films/House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski

SOURCES:

Allen, Woody, dir. Annie Hall. With Allen and Diane Keaton. United Artists, 1977. DVD. 93 min.

Allen, Woody. Getting Even. New York: Vintage Books, August 1978.

Allen, Woody. Side Effects. New York: Ballantine Books, 1981.

Allen, Woody. Without Feathers. New York: Ballantine Books, 1990.

Barnet, Syvan, Morton Berman, and William Burto, eds. An Introduction to Literature. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1974.

Barth, John. Chimera. New York: Fawcett Crest, 1988.

Barth, John. The Friday Book, or, Book-Titles Should Be Straightforward and Subtitles Avoided: Essays and Other Nonfiction. New York: G.P. Putnam‟s Sons, 1984.

Bergman, Ingmar, dir. The Seventh Seal. With Max Von Sydow, Bibi Andersson, and Gunnar Bjornstrand. A.B. Svensk Filmindustri, 1957.

Crumb, Aline Kominsky. Need More Love. New York: MQ Publications, 2006.

Crumb, Robert and Peter Poplaski. The R. Crumb Handbook. London: MQ Publications Limited, 2005.

Eisner, Will. Last Day in Vietnam: A Memory. Milwaukie: Dark Horse Comics, 2000.

Epstein, Daniel Robert. “Need More Love: Talking to Aline Crumb.” Newsarama.com. Viewed 9/6/2007.

Gloeckner, Phoebe. The Diary of a Teenage Girl: An Account in Words and Pictures. Berkeley: Frog, LTD., 2002.

Higgins, Dick. “Synesthesia and Intersenses: Intermedia.” Something Else Newsletter 1, No. 1. 1966.

Holland, Stephen. Rev. of Need More Love by Aline Kominsky Crumb. Line of Fire Reviews, www.silverbulletcomicbooks.com. Viewed 9/6/2007.

Kennedy, X.J., edt. An Introduction to Fiction, Third Edition. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1983.

Koster, Henry, dir. Harvey. With James Stewart, Josephine Hull, and Charles Drake. Universal, 2000. DVD. 105 min.

Lucey, Paul. Story Sense. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996

McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: The New American Library, 1964.

McLuhan, Marshall and Quentin Fiore, produced by Jerome Agel. The Medium is the Massage. Corte Madera: Gingko Press, 2001.

Moore, Terry. “Basic Training: How to Draw Realistic Women.” Wizard: The Guide to Comics #71 (July 1997): 76-79.

Napierkowski, Marie Rose, ed. "Storyteller: Introduction.” Short Stories for Students Vol. 11. Detroit: Gale, 1998. eNotes.com. January 2006. 23 October 2007. <http://www.enotes.com/storyteller/introduction>.

Scofield, Sandra. The Scene Book: A Primer for the Fiction Writer. New York: Penguin Books, 2007.

Silko, Leslie Marmon. Almanac of the Dead. New York: Penguin Books, 1992.

Silko, Leslie Marmon. Ceremony. New York: Penguin Books, 1986.

Silko, Leslie Marmon. Storyteller. New York: Arcade Publishing, 1981.

Silko, Leslie Marmon. Yellow Woman and a Beauty of the Spirit: Essays on Native American Life Today. New York: Touchstone, 1997.

Talbot, Bryan. The Tale of One Bad Rat. Milwaukie: Dark Horse Books, 1995.

Wittlinger, Ellen. Hard Love. New York: Aladdin Paperbacks, 2001.