The Well in Pollone: Chapter Two

Eventually we reached Pollone, and I was far from being disappointed. It was a charming village, and everything nice that Umberto had said about it had fulfilled all my expectations. We drove at speed through the little lanes and along the wider roads and then turned down a very narrow lane, so narrow that there certainly wasn't room in case any other vehicle should be coming from the opposite direction. We passed one old lady, dressed completely in black, who smiled and waved a friendly hand at Anna. I had realised whilst passing through Pollone that Anna seemed to be known to almost everybody, as there was the constant calling out of: “Ciao, Bella,” and “Ciao, Anna,” to her and “Ciao, Bello or Ciao, Bella,” from her; and I knew instinctively that I was going to love being among these lovely friendly people.

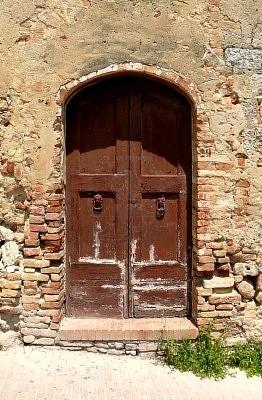

Halfway down the narrow lane we stopped beside a huge, old wooden door in the wall and Anna jumped out, took a large brass key, similar to a Yale key, and opened the lock. It was a triple throw lock, and she opened the door inwards and we both entered.

It led us into a tree shaded courtyard.

Having entered through the great door, we stood in the tree-shaded courtyard.

To the right was a set of simple open wooden stairs with a handrail.

Those open stairs led to the little area where Umberto had his simple “apartment”. It was a conversion from some sort of bucolic arrangement. Umberto’s living quarters were on the first and second floor and were comprised of three rooms.

Anna turned to the right, and pointing upwards to an open fronted balcony with a rustic wooden balcony rail, turned to me and smiled: “Umberto’s. Yours”.

His “apartment”, and those of the other tenants, appeared to have formerly been either hay lofts or some form of open fronted storage; part of a farm building; perhaps. Or perhaps I was being too romantic and they had always been dwellings. Three or four of these “conversions” overlooked the central area which contained the great chestnut tree and a beautiful old well. Umberto’s accommodation comprised a large open area with a kitchen at the back and an open wooden stairway to the bedroom; off that, a large open balcony. Not so much a flat as three rooms overlooking a fairly spacious courtyard.

Then taking both my bags, Anna bounded up the stairs to the second floor. I followed, and she quickly showed me around. Then, although not using words, but simply by gestures, she let me know that she had to be somewhere else, but would return later for “Pranzo”, indicating eating by putting her fingers to her mouth, “Mangiare, mangiamo”; to eat, we would eat.

Then, as she was obviously in a hurry to be that somewhere else, she came down the stairs. As she was leaving, and we were saying our “Arrivedercis”, she stopped with her hand on the big door that led to the lane outside; casually pointed at a door in the wall that faced Umberto’s apartameneto. “Gabinetto,” she said, laughing. “Questo è il tuo gabinetto”.

And there it was. My gabinetto; my lavatory. Directly opposite my new home, on the other side of the courtyard, was a wooden door; behind this door was the lavatory. Had Umberto told me that I must use that as there was no lavatory in his three rooms? I can’t remember, but my first experience of the lavatory at Umberto’s home was traumatic.

I’d seen “gabinetto” on the train and knew that that meant “lavatory”. In fact I’d read a lot of words and phrases which I assumed meant something that I would need one day: On the aeroplane I had been assured that la salvagente è sotto la poltrona and I assumed that that meant that if we fell out of the sky I would be saved by looking under my seat, or my throne, to find it… possibly a life jacket. I had been encouraged on the train to non gettate alcun sulla finestra,which led me to believe that I shouldn’t throw anything out of the window… and acqua potabile was an easy one… That meant that the water was drinkable, I suppose. But what about aqua non potabile?

I was on a roll. If I could cope with all of these, I was pretty sure that I would never make the mistake of eating a cat on the train; or at least not admitting to it. And the thought of losing my wet nurse at the Central Station in Rome was hardly likely

Anna left. And, almost immediately, I heard her car start up and roar up the narrow lane. “Thank God,” I thought. I didn’t want her to go particularly, but I hadn’t used the lavatory since I was on the train from Rome. It had been a hot day, and I had drunk water and limonata to quench my thirst, and several cups of caffè espresso hadn’t helped. The cups were tiny, but coffee is a diuretic, and caffè espresso is more so. I was absolutely dying to use the lavatory… my gabinetto.

I looked into it and although I was dying to relieve myself I found it difficult to enter. I am sure that if anybody had been watching, I would have been seen to recoil; to recoil dramatically.

It was a room a little over one and a half metres square with a rough concrete or stone floor with a hole. On either side of the hole were two raised shapes; the size and shape of a footprint. It was obvious what they were for. Put your feet on the foot shaped plinths - guide and lower yourself to within a safe distance of the hole… and defecate.

I couldn’t do it.

I knew that even in a dire emergency, that I could never squat within a safe distance of that hole and aim my poo at it with any accuracy or safety. But I had been travelling all day and had stopped in Biella for an espresso and now my bladder was telling me in a very loud voice that, no matter my fears of falling down the hole in the near or far distant future it wanted to be relieved, and to be relieved at once.

Of course the hole was far too small for me to fall down it, but I wasn’t going to take any chances.

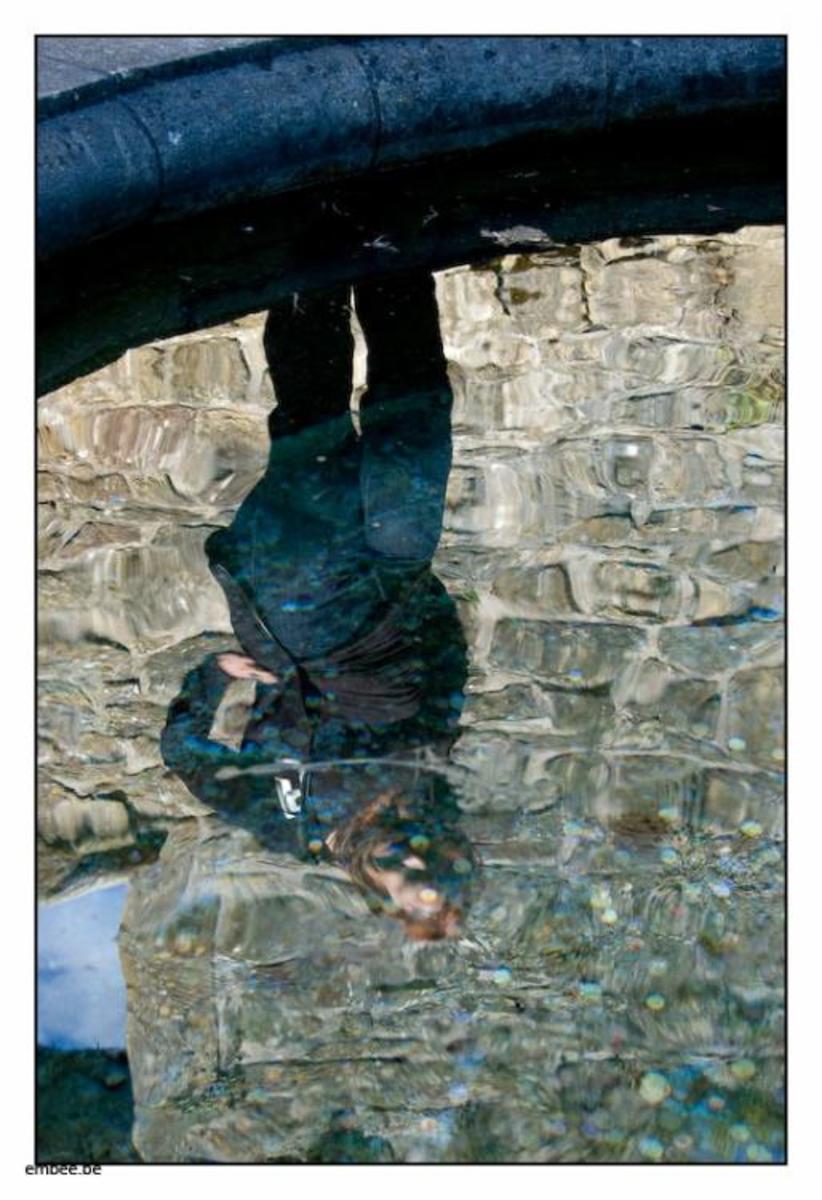

I entered the little room behind the wooden door. I closed the door as securely as I could; considering there was no lock; just the remains of a wooden bar which at one time had slipped into a notch… my arm stuck out behind me, holding the door closed with one hand, I stood and I urinated… I peed with what care and accuracy that I could muster, down that hole and was horrified to hear my piss splashing metres beneath my feet in what I assumed was some massive amphitheatre of sound. The gushing sound of my piss embarrassed and shocked me. I felt that half the population of Pollone would have heard me. But when I eventually took courage and opened the door of the gabinetto and peered outside, my worst fears were unfounded. No one was there. Just me and an empty courtyard. The sun filtered down through the leaves of the chestnut tree, a bird chirruped reassuringly in the distance. All was at peace. No one had heard.

Or so I thought.

Suddenly from behind me, a door opened and a very old lady darted out of a door on the ground floor. She carried a brush and a pail of water in her hands. She entered the gabinetto. There was a sound of brushing and sluicing and scrubbing, and then, after a few moments, the door flung open again, revealing the old lady, happy and smiling.

This episode, brief as it was, reminded me of one of a pair of lovers in a Tyrolean chiming clock. The pair of lovers who come out on the hour and on the half hour; one from a little cabin on the left; one from a little cabin on the right. They come out at the chiming clock’s call and meet in front of a tiny little Tyrolean castle; bend briefly; kiss each other even more briefly and then turn to resume their places in their little huts to wait for the next half hour.

But in this non-chiming nightmare, there was no chiming clock; just the sound of a closing wooden door. And rather than a pair of Austrian lovers; he in a military uniform; she in a dirndl skirt, with her hair in yellow plaits, there was an old lady with a brush and a pail of water.

“Buongiorno” she almost shouted and then there followed a string of Italian words that I didn’t understand at all. Basically I think she was saying something like: “You’re the one who had a piss and emptied your bowels and I cleared it up for you”.

Before I could respond; before I could tell her that I had only peed down that ghastly hole, and that I hadn't even attempted to open my bowels, she had darted back through the door she had come through; and no doubt lay there waiting for the next person to use the hell hole I had just vacated. Should I have tipped her? Should I have said anything?

“Thank you!” I muttered, feeling my face darkening with embarrassment… “Thank you”.

She stuck her head out of her doorway for a quick look at me:

“Prego!” shouted the old lady and darted back into her little home; room; cupboard.

During the whole time that I lived in that apartment, I never heard her say anything that I could understand apart from “Buongiorno” or “Prego”. Prego, the classic Italian word that shows acceptance of a compliment, a thank you for a thank you. “That’s all right” or “It’s my pleasure”.

The well was everything that the gabinetto was not. The gabinetto was a sordid little room behind an old wooden door; a door that was so old and cracked with age that I was convinced that anybody could see into it from wherever they were in or overlooking the courtyard. I had sworn, after the first time I had used it on the day that I had arrived that I would never use it again… unless in an emergency or under cover of darkness. For whenever I had seen anybody use it, whoever it was, that old woman with the brush and the pail of water would scuttle into it as soon as it had been used, and then she would clean it. And make such a fuss about doing it too. Every time she finished she would bellow “Prego!” at anyone who had used it.

I never knew if she was paid to clean up after everyone or whether she owned it or whether she just enjoyed sluicing down every time it was used, but I never defecated in there once during the whole two weeks I was living in Pollone.

My gabinetto and also my bagno became the stream which was over two stone walls and across three meadows. Not fields; fields are places where people grow things; meadows are expanses of grass; wet grass where cows graze and leave cow pats.

My bathroom; my gabinetto, my bagno, was that stream over those fields and walls.

In the heat of the August midday sun, the enclosed courtyard would have been stiflingly hot, but a large sweet chestnut tree grew in the centre of the courtyard, pushing its massive trunk up through the heavy, rough hewn stone slabs. This courtyard was overlooked by the three, or more, other sets of rooms belonging to the other tenants.

I never discovered how many people lived in the dwellings overlooking the courtyard. I would see people coming in, in the afternoon for their lunch, or perhaps I would catch a glimpse of someone, in the morning, when I went to the well, but that was all.

There was nobody there during the day as the other dwellings were owned, or rented, by the people who worked in local industries; on the farms surrounding the village or as servants perhaps in the big villas further up at the other end of the village. The population of the whole village numbered a little over two thousand.

The well stood near but not directly under the chestnut tree. It was built of local grey stone and aged brick, and beautiful in a charmingly rustic manner. Two solid stone pillars rose to hold up the simple tiled roof. A solid wooden beam stretched between the two columns from which the ancient bucket hung. An iron handle, for turning, stuck out at the side, but was difficult to turn so that would draw up the bucket. From my first days that bucket stood on the edge of the mouth of the well. There was a little stone skirt, or step, which ran around the base of the well for one to stand on or for a resting place for the bucket when it had been drawn up with water from below.

When I first arrived, it had been decorated with red geraniums in pots, but I put these to the side and brought down the bucket so that I could use it to draw the fresh, sweet water that lay don in the coolness of the earth.

I loved that well and the sweet water that I drew from it each day.

During my all too brief stay in Pollone, that well became an intrinsic and much loved part of my morning ritual.

I was woken before dawn by the Clonc! Clonc! Clonc! of the cow bells hung around the necks of cows as they were driven up into the low mountain pastures for the day. I lay in bed and listened and then perhaps dozed off to sleep again; enjoying the glorious mountain air, and then the smell of someone making coffee in one of the other homes nearby.

Umberto had told me to use whatever I found in the kitchen and to call the place mine for the duration of my stay. Yet, on the second day, I discovered a little negozio, a shop; just at the end of the lane that Anna had driven down on that first afternoon. Everything that I should need to make my breakfast was available there: panettone, a wonderful homemade albicocca conservare (apricot conserve), latte in a carton, and Lavazza caffè grounds; my favourite.

I had discovered an espresso caffè machine in the simple kitchen, and ignoring the large plastic bottles of water, wrapped in plastic, I would go to the well, draw up a bucket of cool water from it and then set about making my breakfast. It was an idyllic existence.

The espresso machine was capable of making vast amounts of caffè, and I would sit on the wooden stairs in the sunshine; drinking the caffè in a huge coffee bowl, and eating the panettone with fresh butter and the sweet but tangy albicocca conservare.

Then, as unobtrusively as possible, I would take my towel and soap and saunter off to take my morning bath in the stream that I could reach by crossing those damp, dew drenched morning meadows. That stream, fed by the melting snows from the mountains that rise above Pollone.

I splashed in the near freezing water like a child. I threw water in my face and over myself like a young boy again. I squatted silently and as secretively as possible and used the fresh water where toilet paper would usually be used.

One morning I was laughing and chattering to myself in my bath, my bagno, my gabinetto. I felt that eerie feeling one experiences when one is being watched, and turned to see a lone cow, watching me with that gentle look only a cow can show,

“Buongiorno!” I called to her, and continued washing myself as if I were the only man in Northern Italy.

“Buongiorno!” came a sweet voice, and I turned and I looked; my body and mind transfixed; two young children watching my every move. The boy turned to the girl, and then, laughing, they ran off across the dew drenched grass. I could hear their sweet voices calling out as they ran; their laughter filling that magical morning meadow.

After my bath, I would amble back to Umberto’s home… my home; enervated and happy from my stream. Then, I’d dress and wait to see what my friends had planned for my day.

Living there was charming in the extreme. It was a chance for me to relax, and to just be myself. Nearly all of my meals were taken away from Umberto’s home, which I was already treating as my own, as he had encouraged me to do. Anna had taken me around the village to meet others of Umberto’s friends and they all made a point of making me feel like an honoured guest, but at the same time, part of the social circle. The new friends I made differed remarkably in many respects from each other: from Madalena who owned the bar, to Anna, of course; then another lady, Olga, who took me very much under her wing and made it her mission to introduce me to some of the best restaurants and little eating places I have ever experienced. Everyone was charming, as only the Italians can be.

I was invited out for lunch or for dinner at so many people’s homes, villas and apartments; but more usually, I was taken to restaurants, mostly during the daytime, so that I basically didn’t have a chance to prepare or to have a meal in Umberto’s home until the last evening of my stay in Pollone. I was only there to sleep and to take breakfast, which became quite a ritual.

Biella vecchia

This story (for want of a better word) is in five chapters. The links are here below.

- The Well in Pollone Chapter One

In northern Italy there is a province known to the world as Piedmont. It is an area that for centuries has been invaded by Romans, Burgundians and Goths. It has been annexed and reinvaded by Byzantines, Lombards and Franks. Magyars and the Saracens c - The Well in Pollone: Chapter Two

Eventually we reached Pollone, and I was not disappointed. It was a charming village, and everything nice that Umberto had said about it had fulfilled all my expectations. We drove at speed through the little lanes and along the wider roads and then - The Well in Pollone Chapter Three

On the first Sunday morning of my stay in Pollone, I was sitting on the stairs; basking in the sunshine when a heard a voice. Buongiorno, I looked down to see Olga standing, just inside the great door. She was wearing a light skirt and blouse; her - The Well in Pollone Chapter Four

Not all meals were in expensive restaurants. One evening, Olga drove us to a village on the edge of Lago Maggiore. We entered a piazza in the centre of the village. The piazza was surrounded on four sides by four or five storied houses and apartments - The Well in Pollone Chapter Five

But, as they say, all good things must come to an end. Days stretched into almost two weeks, and I had to return to London far too soon. I had enjoyed myself enormously. On the day before I was due to leave, I was about to take one of my last breakfa