Turning all to Honey: Imitation, Originality, and Authorship in Renaissance England

In the final chapter of Popular Cultures in England: 1550-1750, Barry Reay states that “Historians have an unavoidable transferential relationship with the past.” In trying to understand events that we have never experienced, we inevitably project our own ideas and conceptions onto the objects of our studies, meaning that ultimately, “a historical criticism that seeks to recover meanings that are in any final or absolute sense authentic, correct, and complete is in pursuit of an illusion.” Yet it is clear that there is value in the attempt, as Reay quotes Robert Darnton earlier in the book: “When we cannot get a proverb, or a joke, or a ritual, or a poem, we know we are on to something. By picking at the document where it is most opaque, we may be able to unravel an alien system of meaning. The thread might even lead to a strange and wonderful world view.” Although Darnton is referring to early modern witchcraft in this quotation, there are a number of other cultural differences between early modern England and the present world to which it might just as easily apply, including the notion of authorship.

In his chapter on orality and print culture, Reay describes an early modern England in which the lines between literacy and illiteracy blur, in which some are able to write, some only to read, and even the entirely illiterate are not totally excluded from the influence of print culture, acquiring literate helpers to read and write for them. Additionally, although books were too expensive for the majority of the population to afford, alternate versions of classics like The Canterbury Tales were available in smaller, cheaper ballad or chapbook forms. Thus through Reay, we are introduced to a world with a very free media, in which accessibility to literature is not confined to the signature literate or the wealthy and individual works are not confined to their original authors or mediums. Although Reay does not delve deeply into the subject of authorship and intellectual property, the free appropriation of others’ works widely accepted and encouraged in this period has been a subject of interest for literary historians since the early twentieth century.

However, the initial refusal of literary critics to accept the large degree of importance accorded to the author by the modern mainstream was not actually grounded in historical analysis. Instead, it began with the rise of New Criticism, a theory which sought to examine texts independently from outside influences, including historical context and biographical information about their authors. However, the work of Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault later expanded on this rejection of the author, proposing that authorship is actually a cultural construct rather than an “ahistorical given,” suggesting that intellectual property has been approached differently in the past and may yet be reconceptualized in the future. The concept of discourse not as an action, but as a commodity and the author as producer and owner of that commodity arose, according to Foucault, from a need to hold authors responsible for expressing transgressive ideas. From this original idea of ownership, a complex system of intellectual property rights was created, which Foucault dates to the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century (Foucault), although the first English copyright legislation was passed in 1709, and claims of “authorship” date back to the mid-seventeenth century before reaching their full fruition in the Romantic movement, when “an extreme assertion of the self and the value of individual experience” began to overtake previous notions of authorship as a craft to be learned and perfected through the imitation of one’s predecessors.

According to Foucault, the author is a limiting principle. Because of intellectual property regulations arising from the notion of author as owner and because of our need to ascertain the author of a work before we feel able to truly assess its value, the author “impedes the free circulation, the free manipulation, the free composition, decomposition, and recomposition of fiction.” Prior to this shift towards our current conception of the author as originator and owner, a great degree of value was placed on (often uncited) imitation or “recomposition” of other works. As far back as Plato and Aristotle, the artist’s craft was thought to be one of imitation or mimesis of the natural world, and this idea was quickly expanded to include imitation of other artists. “Roman sculptors based their statuary on Greek originals, Roman playwrights drew on Hellenic plots, while the schools of rhetoric in which the Roman writers and orators were trained employed literary models as means of inculcating the principles of composition.”

By Tudor times, this idea of imitation had expanded to become the basis for an entire educational philosophy. In Roger Ascham’s 1570 pedagogical work The Schoolmaster, it is suggested that the study and translation of Latin texts will “bring forth more learning and breed up truer judgment than any other exercise that can be used.” Sir Philip Sidney writes in his Apology for Poetry (c. 1581-3) that “the highest flying wit [must] have a Daedalus to guide him. That Daedalus… hath three wings to bear itself up into the air of due commendation: that is, Art, Imitation, and Exercise.” Ben Johnson similarly required “natural wit,” “Exercise,” and “Imitation” of the ideal poet.

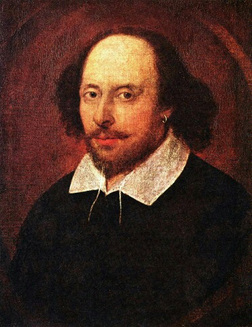

While a modern reader may interpret such use and reuse of another author’s work as uncreative at best and criminal at worst, the conception of literature in Tudor and early Stuart England was much closer to that of a carefully honed craft than that of a spontaneous, individual art. As George Puttenham wrote in his 1589 Arte of English Poesie, “[poetry] be not exactly knowne or done, but by rules and precepts or teaching of schoolemasters… [The poet] may both vse and also manifest his arte to great praise, and need no more be ashamed thereof, than a shoemaker to haue made a cleanly shoe, or a carpenter to haue buylt a faire house.” Thus it was that even Shakespeare, regarded by modern readers as a creative genius, drew heavily from the works of Plautus and Ovid, from traditional folklore, from history, and from the works of his own contemporaries.

However, this value for imitation does not mean that early modern authors were simply copyists. The same writers who advocated imitation insisted that poets were born and not made and that imitation was merely a tool through which one nurtured and cultivated an innate poetic genius. Although Jonson does advocate “turning the substance, or Riches of an other Poet, to his owne use,” he also insists that the poet should do so “Not, to imitate servilely… but, to draw forth out of the best, and choisest flowers, with the Bee and turne all into Honey.” Therefore, Tudor England exemplifies a society unimpeded by legal restrictions on “the free circulation, the free manipulation, the free composition, decomposition, and recomposition of fiction” Foucault says the concept of authorial ownership serves to stifle.

In addition to this free circulation of ideas, Charles Whitney suggests that the early modern penchant for imitation and adaptation may have led consumers of literature to engage more actively with the media around them, using others’ text “as a groundplot to their own invention,” noting that “Early modern audiences freely appropriated lines from plays, just as playwrights did.” This tendency might be best illustrated by the contemporary custom of keeping a “commonplace book,” a collection of passages collected in private reading for later use and review.# Although this custom may perhaps show a greater value for the emulation of authorities than is held by modern readers and writers more concerned with originality, it also shows that reading may have been a more active process for early modern readers, who felt comfortable regularly appropriating text and putting it to use in their own speech and writing.

Through an examination of the different concept of authorship held by early modern people, it becomes apparent that media was not only free in the sense of the wide circulation, even to illiterate groups, pointed out by Reay, but also in the sense that writers and even audiences were able to freely draw from the ideas and writings of their predecessors and contemporaries, unbound by regulations concerning intellectual property. It also serves to debunk modern conceptions of adaptation as inferior for its lack of originality, given that Shakespeare’s golden age of Elizabethan drama relied heavily on the reworking of preexisting material. Observations like these are some of the most fruitful that we can draw from the study of history, discovering “strange and wonderful world view”s that illustrate alternatives to modern ideas we might otherwise take for granted as universal and absolute.