The Afrikaner Mestiza

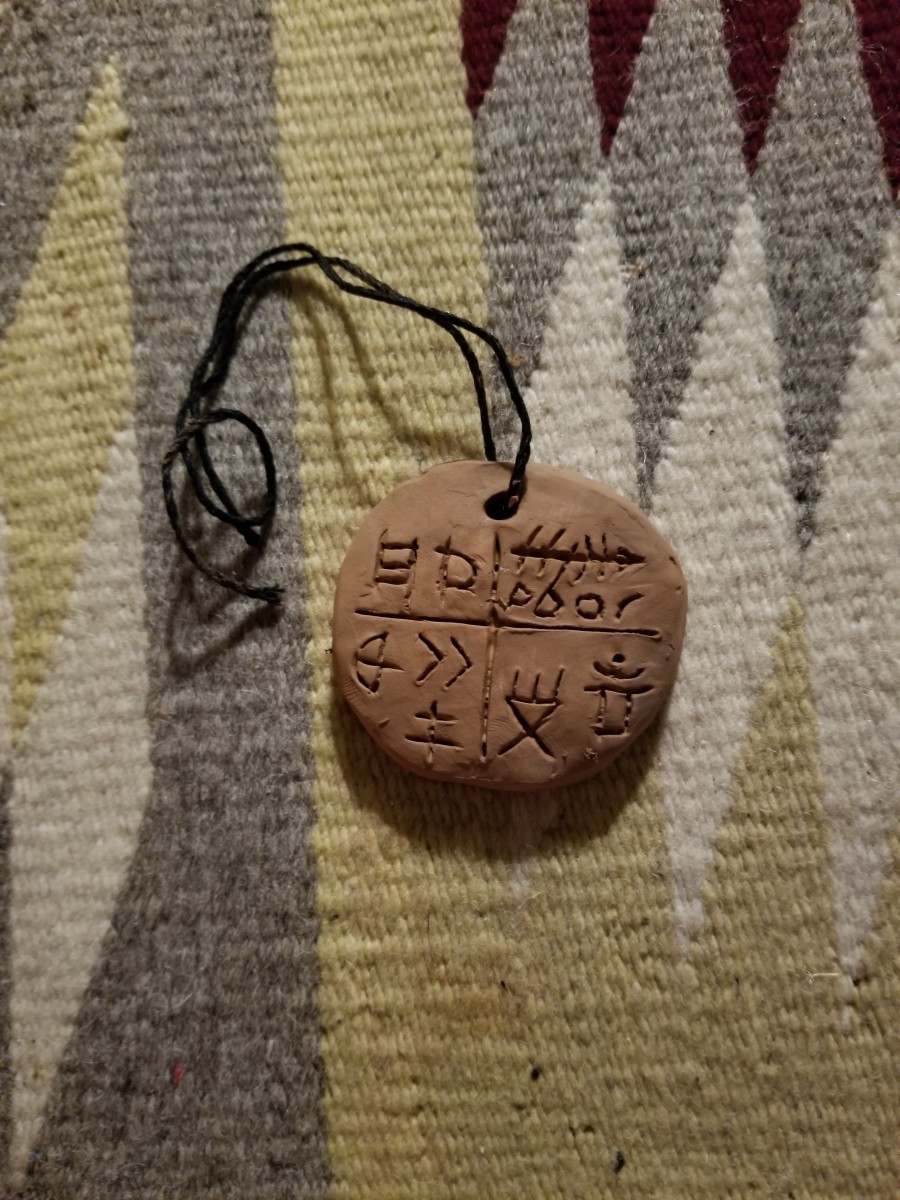

The linguistic pidgin

South Africa’s rich post-colonial background draws on many aspects of identity and the complex concept of origins within the wider world. In fact, origins and their associated consequences are taken so seriously in South Africa that it seems impossible for the country and its neighbours to leave the subject alone politically; others may consider the question a topic for study instead of a daily issue. Ever since the advent of democracy with Nelson Mandela in 1992, colour and origin have been at the foreground of what it takes to belong in Africa. Whilst ‘African-ness’ has always been associated with having dark skin, having dark skin in Southern Africa has until recently signified social and professional impotence. This paper explores the themes of language, borders and social injustice, and will compare Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera with the plight of the Afrikaans speaker. Instead of likening Anzaldúa’s themes with those of the black South-African, I will equate them with those of the Afrikaner in post-colonial Africa.

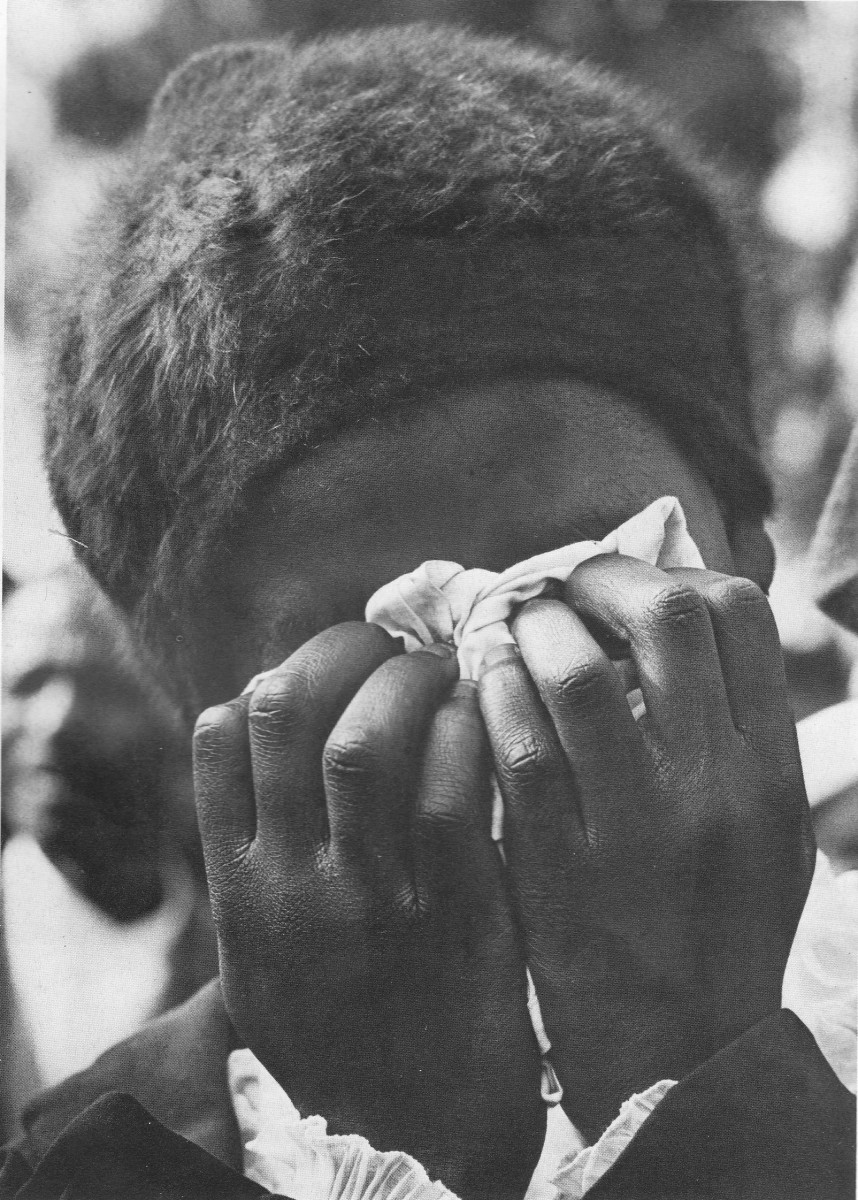

Borderlands/La Frontera is both a historical and auto-biographical text, written in formal and informal registers[1]. A woman living simultaneously in two places, with two identities, two cultures and multiple languages, Anzaldúa writes about the frustrating dilemma of the Chicano people and their desire for a recognised nation-language. She combines prose and poetry, past and present and scatters emotive Spanish in order to make the physicality of the essay less arbitrary in accordance with her objective: to recreate language for the mestiza. In other words, a language that would be used by a gay, multilingual, Mexican woman of colour, instead of the language encouraged by dead white European men - in other words, Canonical literary discourse. Depicting nearly every subject as constituting binaries, Anzaldúa highlights the unavoidable effect that the explicit and the implied borderlines has on those it accommodates. She shows that it is not a matter of choosing an identity, but of living with the aspects that make up a personality which may include more than one identity. This is a practise that Ntozake Shange experimented with successfully in the choreopoem For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf (Scribner 1997).The distinctly female African-American’s voice is only possible when implemented in this vernacular. By phoneticising the syntax of her ‘everywoman’, Shange rejects the canon and everything it represents, challenging hypotheses of the ‘literary’[2]. Anzaldúa is aware of this hazard and “understands that mestiza rhetoric must be deployed tactically:”

"Ok, if I write in this style and I code-switch too much and I go into Spanglish too much and I do an associative kind of logical progression in a composition, am I going to lose those people that I want to affect, to change? Am I going to lose the respect of my peers…?"

The Afrikaner is comparable to the mestiza in accordance with the restrictions placed on their respective languages. A vernacular that initially belonged to Africans who were not African nor European, Afrikaans had to overcome much hostility in order to survive. The language originated from settlers with the Dutch East India Company who established themselves in Cape Town with the intention of providing refreshment to passing ships. The country developed as demand for supplies grew and the potential for larger profits stimulated the new European inhabitants, and the language evolves as rapidly as the country. Dutch began to change and many believed that it was largely due to European interaction with indigenous Khoikhoi: “A bad sort of Dutch… Afrikaans was, in its essence, a dialect of Dutch that had over time undergone a limited measure of creolization or deviation from the basic Dutch structure” [3] From the outset – and a direct consequence of a lack of good education – Afrikaans was associated with the lower and common people, and condemned. No-one wanting to be taken seriously spoke Afrikaans. Like Chicano Spanish, it was “a bastard language.”[4] Only when well educated people claimed it as their mother tongue could Afrikaners cease to be ashamed to use it as their medium of choice and to write in it.[5]

For Chicanos to be denied their own tongue by the Americans was infuriating, but rejection by the Spanish for speaking an inferior language was blatantly degrading. Labelled “Pocho” and “traitor[s]” by other Spanish speakers for speaking the “oppressor’s language”[6], the Chicanos were not allowed the freedom of choosing their mother-tongue:

Chicano Spanish sprang out of the Chicanos’ need to identify [themselves] as a distinct people. [They] needed a language with which [they] could communicate with [themselves], a secret language. (1587)

While the above quotation attempts to explain the observable changes Chicanos made to the Spanish language, Anzaldúa contradicts this statement when she says that Chicano Spanish and Tex-Mex are a “result of the pressures on Spanish speakers to adapt to English.”[7] As a Chicana, she is part of a larger system by virtue of what she lacks: her ‘poor’ use of the language identifies her as an ‘other’ and the colour of her skin ensures that she is rejected from the ‘main’ body that makes up the human race. Although she and other “Spanish speakers will comprise the biggest minority group in the U.S” (1888), they are ironically seen as a minority, a ‘group’ of people who do not merit the same privileges awarded the English on the other side of the ethnical demographic. The topics Anzaldúa concerns herself with explores and voices her displeasure with the majority’s points of view concerning ethnicity and sexual orientation; with particular attention paid to the plight of the mestiza who embody both of these.

I believe that Anzaldúa includes Chicano men in her estimation of mestiza (by referring to ‘Chicanas’, whereas she could have written ‘women’[8]), thereby emphasising the complicated position of the Mexican. If a man of colour is not wholly a man, as a white man is, does that make him a woman? Up until the contemporary (and in many places still), “[black males were coded as automatically criminal] and race usually implies crime and disorder” [9]. The context of traditional sexual politics is inverted when the feminist steps up to protect the man in her community from prejudice. Perhaps this is the ultimate form of feminism – the capability of protecting their men; to show that women are not weak by nature, but that they may be occupying a space where they are unable or forbidden to exercise strength; the same way the Chicano man is in a vulnerable (or woman’s) position by virtue of the social space he occupies.

Due to the linguistic oppression instigated by their teachers[10] and parents[11], Chicanos were placed in the position of being unable and unwilling to speak either English or Spanish freely. The former belonged to the oppressor; a conqueror’s language that was forced on them. The latter was an abstract ideal, denied the Chicanos due to linguistic evolution. This borderline quandary created the problem of speaking even to each other because

"[even] among Chicanas [they] tend to speak English at parties or conferences. Yet, at the same time, [they’re] afraid the other will think [they’re] agringadas because [they] don’t speak Chicano Spanish".[12]

Being an Afrikaner, I have found that we have a similar problem. Once removed from an Afrikaans environment, we tend to switch to English in other Afrikaner's company. The Afrikaner has grown up being ridiculed for his/her language and has adopted a passive-aggressive stance. Like Chicanos who “[try] to out-Chicano each other, vying to be the real Chican[o]s” (1588), Afrikaners may become belligerently ‘Afrikaans’ when in the exclusive company of other Afrikaners. When they meet outside of South-Africa, the Afrikaner feels safe from the ‘English-man’ as his/her ‘secret’ is safe; that is, the guild and embarrassment a propos their mother-tongue. To many an Afrikaner's way of thinking, non-South-Africans will not understand the underlying animosity between the two language-types, and therefore not judge the Afrikaner as the English South African is wont to.

Whilst Chicanos’ Spanish changed in accordance to their oppressors’ language, Afrikaans changed according to their inferiors’. The Dutch language underwent transformation due to an intermingling with native tribes and an inferior language developed accordingly. Although the Dutch struggled to smother it, Afrikaans eventually overcame stigma to the degree that it was recognised as a ‘white man’s language’, although it had originated from both ends of the racial spectrum. It was an amazing feat for a pidgin tongue to accomplish. However, this short-lived language is rumoured to be dying out. Whilst there is no concrete evidence for this occurrence, popular speculation predicts that in the contemporary world, it is only a matter of time before Afrikaans comes to a standstill. Breathless articles tell of how white English pupils choose African languages as subjects instead of the (once required) Afrikaans as second language.[13]

According to Anzaldúa, the inadequacy felt by Chicanos in regards to their language is due to peer review. Snubbed by ‘real’ Spanish speakers and physically punished by the English[14], Chicano is an identity that has had to work hard in order to survive by virtue of being a minority group. Falling under the term ‘minority’ categorises oppression; minorities weren’t merely avoided – they were actively victimised due to their heritage, language, sex or other ‘defect’ which are purely accidents of birth. As stated by Louise Viljoen, an expert on Afrikaans literature:

"Although cynical words have been spoken about the current popularity and academic marketability of postcolonial theory, it cannot be denied that it has provided valuable new perspectives on the world's so-called 'marginal literatures'. One's understanding of postcolonialism is largely determined by the way in which the prefix post- in postcolonialism is read. If it is read as a reference to temporal succession and even supersession, the term postcolonialism applies to that which follows after colonialism. If however colonialism is defined as the way in which unequal international relations of economic, political, military and cultural power are maintained, it cannot be argued that the colonial era is really over."[15]

Like the Chicano, the Afrikaner is neither coloniser nor colonisee. They are borderland minorities because they stand out no matter where they go due to the newness of their languages. This won’t last forever though. Language evolves continuously and certain educational institutions now offer to overlook ‘text-speak’ in academic examinations. Although this is something that would cause Sven Birkerts to break out in a cold sweat and a mad rant, it also suggests that if the same institutions that teach Chaucer will accept ‘l8r’, pidgin languages will eventually be taken for granted.

The minority is increasingly becoming the norm.

[1] (The main body of text is a formal account acting as narrative. Anzaldúa’s Spanish interjections are more informal and signify her rebellion against conformist linguistic practise. “Oye como ladra: el lenguaje de la frontera - quien tiene boca se equivoca”, which translates roughly into ‘it hears as it barks: the language of the border - the one who has a mouth is wrong’) Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera, in Rhetorical Tradition, 2nd edition. Ed. P. Bizzell & Heizberg. (Boston: Bedford/St Martins, 2001.) (1586)

[2] (“little sally walker, sittin in a saucer/ rise, sally, rise, wipe your weepin eyes”) Shange, Ntozake. For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf. (New York, NY Scribner, 1997), 6.

[3]Hermann Giliomee The Afrikaners. (C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2003), 53

[4] Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/ La Frontera, in Rhetorical Tradition, 2nd edition. Ed. P. Bizzell & Heizberg. Boston: Bedford/St Martins, 2001.), 1588

[5]Hermann Giliomee, 224.

[6] Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands, 1586.

[7] Anzaldúa, 1587.

[8] 1588.

[9] Routledge (Google Books). Jan Pettman. Worlding Woman: “Woman, colonisation and racism” http://books.google.com/books (accessed June 02, 2009).

[10] 1585

[11] (‘“I want you to speak English…” my mother would say, mortified that I spoke English like a Mexican’)(1585)

[12] 1588

[13] (Sibande blames parents for the fact that children don’t want to learn Zulu at school. “Most parents look down on the language. The general feeling is there’s no need to do isiZulu. My argument is: Why do Afrikaans? You don’t use Afrikaans in the corporate world. ”Richardson said he chose Zulu because he thought it would be more helpful than Afrikaans, which he described as “a dying language”) The Times. “ White schoolboy chooses to learn Zulu over ‘dying language’”Published:Nov 09, 2008. http://www.thetimes.co.za/PrintEdition/News/Article.aspx?id=880425 (accessed May 04, 2009)

[14] “I remember being caught speaking Spanish at recess – that was good for three licks on the knuckles with a sharp ruler.”(1585)

[15] Viljoen,Louise. "The Republic of South Africa: in The Postcolonial Literature and Culture Web". Postcolonial Web. http://www.postcolonialweb.org/sa/viljoen/1.html (accessed June 01, 2009).