- HubPages»

- Sports and Recreation»

- Team Sports»

- Baseball

75 Years After His Retirement: The Story of Lou Gehrig's Final Years

The Story of Lou Gehrig's Final Years Playing and Living with ALS

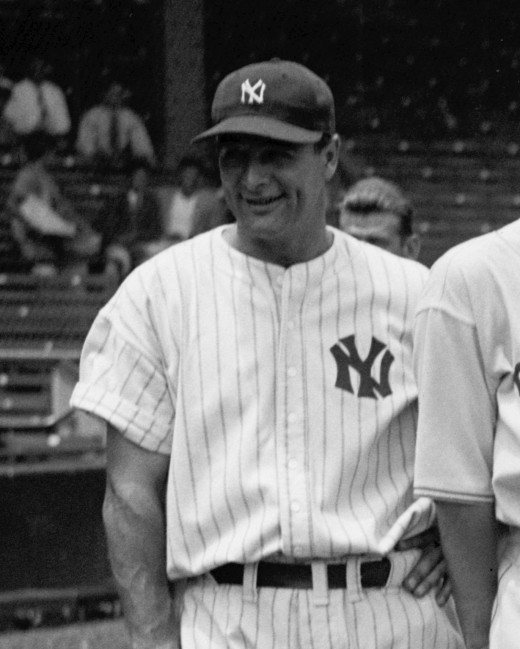

Lou Gehrig is known by many as a baseball legend because of his skills as a hitter and the endurance which led him to gaining the nickname “Iron Horse.” He is also known for having died from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis or ALS in 1941. This is because his case is still by far the most famous; so famous that the disease is widely referred to as Lou Gehrig’s disease by medical professionals. Many know about the disease causing his early death, but there is little focus on the signs of the disease he displayed in his final two years of playing. In these two years, Gehrig saw his statistics drop to career lows and had difficulty with everyday activities. This included stumbling and sliding his feet while walking and falling while putting his pants on. However, these signs went largely ignored by him, his wife, the team, media, and fans. While in reality Gehrig was slowly dying, the majority believed that he was struggling because of natural aging, fatigue from playing for so long, and various baseball-related factors.

What is ALS? ALS is a neurodegenerative disease that progressively affects nerve cells in the brain and the spinal cord. It kills motor neurons which leads to the inability of the brain to initiate and control muscle movement. As a result, the muscles succumb to atrophy and the result is scarring or hardening in the region. Impulses to the muscle fibers that normally result in music movement become impossible. The early symptoms of the disease include increasing weakness in the muscles. This is seen the most involving the arms, legs, speech, swallowing, and breathing. Before Lou Gehrig’s case, the disease was widely unknown to many and little studying was done on it. People who had it were often put in homes for the mentally ill and forgotten about until they died. Even the doctor who had originally treated Gehrig after he began to feel ill refused to believe the diagnosis of ALS and called his wife Eleanor foolish when she had told him the news from his visit to the Mayo Clinic in 1939. The early speculation after the media and fans had heard the news was that he caught it either from a trip he made to Japan with fellow All Stars in 1935 or from playing for so long. However, it is not contagious and the cause is not yet officially known. The news of Gehrig’s diagnosis and eventual death brought about a new public spotlight and an outcry for research on the disease. People saw what it did to a strong man like Gehrig and realized how serious and deadly it was. In the years following his death, significant research has given doctors and families much more understanding about it. Although there is still no cure for it, the research and support following Gehrig’s death has led to the development and approval of the drug Riluzole which slows the progression of ALS modestly.

By the time Gehrig was diagnosed with the disease, he was already one of the greatest players of all time. The endurance he displayed playing in 2,130 consecutive games despite several different fractures and getting hit by pitches on multiple occasions led him to gaining the nickname the “Iron Horse.” This is a record that would hold up for almost 60 years until Cal Ripken Jr. broke the mark during the 1995 season. In addition, he was the best offensive first-baseman of his generation. He hit for baseball’s Triple Crown in 1934, meaning he led the league in the categories of batting average, home runs, and runs batted in. He hit four home runs in one game during the 1932 season, became the only player to drive in more than 500 runs during a span of three seasons, and had an astounding total of 184 runs batted-in during the 1931 season. Gehrig was also the all-time team leader in base hits for the New York Yankees until Derek Jeter broke his team record in the 2009 season. He still holds the record for most career grand-slams in a career with 23. Additionally, Gehrig was named to seven All Star teams and won the American League Most Valuable Player award in 1927 and 1936. Playing just thirteen full seasons, Gehrig accomplished much more than most other players who played for more seasons. He was truly a fan favorite and played the game better than any first-baseman to come before or after him.

Although the primary focus of the paper will be on the years 1938 and 1939, an important incident during the 1934 season warrants discussion because of its impact on the events of these years. On July 13, 1934, Gehrig had complained of developing back pain during the night and in the morning prior to a game against the Detroit Tigers. His trainer told him that it was just part of getting old and he chose to play in the game. However, after being tagged out while being caught on the bases, the pain became so bad that he was taken out of the game and spent several hours with the trainer. He had suffered what is called a “lumbago attack” which is a musculoskeletal and vertebrae problem that is equated to catching a cold in the back. Gehrig did not sleep until dawn the night after and was unable to participate in batting practice before the next game but he insisted on being in the line-up so that his consecutive games streak would still be alive. He had his manager Joe McCarthy put him in the lineup leading off so that he could play one inning and bat once and then sit out the rest of the game but still have the game count for him. The pain went away the next day, and he became angry at reporter, James Kahn, for discussing his back problems. He would suffer from back pain occasionally until his retirement in 1939. Considering that this was the season he hit for baseball’s Triple Crown, it is highly unlikely that this or anything else he may have endured during this season affected his ability as it did in 1938 and 1939. The reason this incident is important to the topic is that this lumbago attack is believed to be the first sign of developing ALS, according to several medical professionals. Back pain was just one of the several ailments he played through for the sake of keeping his streak alive from then until his final game.

Prior to the start of the 1938 season, Gehrig filmed the western movie Rawhide. He had decided to appear in the movie after being discovered by publicist Christy Walsh who suggested that filmmaking would be an ideal post-baseball career for him. Between filming the movie, making promotional appearances, and living a glamorous Hollywood lifestyle, Gehrig had little time to prepare for the upcoming baseball season. From this and because of bad eating habits, he reported overweight to the start of Spring Training. To lose the excess weight, he would train extra hard and even run in a rubber suit to sweat off pounds. The extra training and running did not work well as his struggles continued into the beginning of the regular season. On Opening Day, he went hitless against a first-year pitcher and would not get his first hit of the season until three days later. His bad play went largely ignored by writers because they laid the blame for the Yankees’ early losing on Joe DiMaggio’s contract holdout. Gehrig’s slump was believed to be over after getting two hits in one game for the first time in the season on April 30. An article written the following day in the New York Times stated that he was tearing around the bases like the “iron horse” that he was named after.On the contrary, he would go back into a slump and struggle to keep his batting average above .270 for much of the first part of the season, and he did not hit any home runs until two weeks after the season began. He was troubled by not knowing what the cause of his poor performance was. Writers believed that he was simply trying too hard to hit home runs and that this was common for hitters in a slump to do. They believed he was forgetting the good habits that made him a good hitter in the first place, and he was not showing enough discipline at the plate. Another possible reason for his struggles early on was recurring back pain he suffered from in May. He was forced out of a game because of it and underwent diathermic treatment, resulting in him being covered with plasters. Yet, he insisted on at least starting games even though he had noticeable pain. He was one of several key players though suffering from injuries, which meant that the team would be focusing on getting rest for those players while allowing Gehrig to continue his streak.

Gehrig was also rapidly approaching his 2,000th consecutively played game. His wife Eleanor attempted to convince him to stop his streak at 1,999 straight games, reasoning that it make for great headlines and that they could just have a quiet celebration alone. However, Lou was appalled at the idea because he could not stand to let the fans down and he wanted them to get their money’s worth. Adding games to the streak fascinated him and he knew that the team would be giving him a special award for his accomplishment. In an article written after his 2,000th straight game, Gehrig stated that he felt there was no point in resting because he liked to play baseball and that he would worry and fret too much while sitting on the bench. Side-by-side pictures of him published after the game from when his streak began in 1925 and from 1938 showed that Gehrig had become leaner, his shoulders were crumbling, and his uniform appeared larger. It was also reported that he experienced shortness of breath and cramping in his calves which are suggested to be caused by ALS.

Gehrig continued to play in each game for the rest of the season and was able to improve his play. His statistics to end the season: a .295 batting average, 29 home runs, and 114 runs-batted-in, were just average compared to the numbers he had been putting up in his previous seasons. Writers still believed there was good baseball left in him, and Joe McCarthy refused to bench him because he was still better than any other first baseman in his eyes. However, McCarthy did begin to wonder if something was wrong and became somewhat alarmed when Gehrig told him that he was just looking to get a piece of the ball big enough to get little hits as an explanation for not getting his full body into swings. Gehrig also became very defensive about his legs, repeatedly stating that they were just as strong as they were twelve years earlier. He managed to tie the all-time record for consecutive seasons with at least 100 runs-batted-in and broke the all-time record for consecutive seasons with at least 100 runs scored. The Yankees still went on to win the World Series for a third straight season, but Gehrig played a minimal role in the victory. He amassed just four singles in 14 at-bats and did not record a run-batted-in. This did not receive much attention because of the success that other players on the team had, although it did have manager Joe McCarthy begin to speculate about Gehrig’s ability to play full-time and hint at replacements. During the Yankees victory celebration, Gehrig was suspected of being inebriated. Despite consuming only two beers, he was stumbling and falling, and he was unable to open a bottle of ketchup. This was a manipulation of the symptoms of ALS.

The off-season after 1938 ended up troubling for Gehrig. He began by telling reporters that he tired mid-season and just could not get things going again. There was also an article which was very critical of him in which the author believed that Gehrig had a philosophy that the world owed him everything. Additionally, he was bothered by fellow German-Americans who were supportive of Hitler in World War II calling it a disgrace for them to support him. On top of this, he allowed the team to take $3,000 off his salary for the upcoming season because of his off year. Gehrig was determined to have revenge on the playing field for all of these things. Not only did he have to deal with pressure following a sub-par season, but he also was experiencing trouble with things he normally excelled in as well as everyday movements. For example, the once strong skater was falling awkwardly on the ice. He grudgingly went to a doctor after Eleanor and teammates persuaded him to do so, and he was diagnosed with a gallbladder ailment and put on a bland diet. Even with this new diet though, he stumbled while walking and had to wear tennis shoes instead of cleats to slide his feet across the ground while playing golf. Neither he nor his wife thought twice about what the falls meant.Gehrig believed that he was simply growing older and getting tired a little easier as all aging men do. He never believed he had overdone anything. To him, the strain of playing all this time had not gotten to him yet and he had no doubts about coming back strong in 1939. Joe McCarthy had the same confidence in Gehrig. He believed that it was not yet necessary to worry about replacing him because he still drove in over a hundred runs and other first basemen would be well pleased with having the season he had. It was also Lou’s decision to keep playing.

When it came time for Spring Training in 1939, Joe McCarthy received pressure from team owners to make Gehrig a part-time player. An article written on March 13, 1939 argued that sitting or replacing him would be part of ruining the team as he had been a key part of their championship teams since 1926. Lou was cut slack because it was believed to be expected that he would slow up. Observers did not want to say he already had, because he was such a great player and admirable character. Similar to what was said after the 1938 season, the Yankees were not going to find another Gehrig, and it was always a given that he would be there from training camp until the season was over. McCarthy was unimpressed when Gehrig hit two home runs during one exhibition game over a short fence. However, when the subject of replacing Gehrig was brought up again, he said he would keep playing him because the team had so many other star players. He responded to worriers later in the month by stating that slowing down is natural at his age and he always had slow starts in camp. He also said Gehrig was confident in himself and felt fine.It was acknowledged though that he needed a lot of work because he was kicking the ball around and not hitting well. This was followed by McCarthy stating that, looking at his record book, there was no need to worry. While he was displeased with Gehrig’s messing up ground balls and popping up with the bases loaded, he also said this was part of getting into shape.

On March 23, 1939, after forcing himself into extra practice and running, Lou missed a game in Spring Training for the first time in 14 years. There was plenty of speculation that this meant that Gehrig had finally “cracked up” and would be replaced by a capable young player, but McCarthy downplayed the move, stating that he was simply giving him rest. Team president Ed Barrow liked the idea but wanted to see Gehrig at first base. Despite what McCarthy and Barrow had said, the press had much to say about Gehrig’s poor play. He was said to be in less impressive form than in any previous year: his throwing was questionable, he was not fielding balls well, and he was not even a reminder of his old self. His five errors in ten games and five hits in 32 at bats were also lackluster. The reactions of the fans to Gehrig’s play were mixed. On one side, observing fans felt he was a bust and not the great player they had been reading about. On the other hand, there were also optimistic fans who continued to believe in him. One such example can be seen in a Letters to the Editor piece on April 1, 1939 where the media was called out for their bashing of Lou for not being the player he once was. He stated that it was bad sportsmanship on their part. The writer felt he was speaking for all fans that they dislike the constant slams at him and that this had a part in his suffering play.

By the start of the regular season in 1939, discussions began about Gehrig possibly having something wrong with him. Joe McCarthy became more worried about Lou’s health but stood firm in his decision that it would be up to him as to whether or not to rest. Also, an article about his health believing age had caught up to him was posted in the World Telegraph. Former teammate Bill Dickey recalled knowing something was seriously wrong when he saw Gehrig trip with nothing on the floor. Also, reporter James Kahn, who had covered Gehrig for years, wrote in an article that he believed something was physically wrong with him and it goes far beyond his ball playing. His play on the field considerably reflected what had begun to be discussed. His friendship with McCarthy allowed him to still bat fourth in the Yankees line-up but he moved down before long. He had just five hits, four of which were weak singles, in the first eight games of the season. For the first time in his career, a pitcher intentionally walked the batter in front of him in order to pitch to him. Gehrig promptly hit into a double play and ended the inning. The pitcher in this instance, Lefty Grove, along with others who faced Gehrig wondered if something was wrong with him. Ted Williams, a Boston Red Sox legend, said after the game that Gehrig had just swung down on the ball and still had amazing power. His ability to field was diminishing also. He had to drag his feet across the dirt to step on first base and there was one instance which really got into Gehrig’s mind and made him contemplate quitting. In the 9th inning in a game against Washington on April 30, pitcher Johnny Murphy ran very quickly to cover first base on a routine ground ball so that Gehrig did not have to move to the base. The team congratulated Gehrig for a “great play” but he saw this moment as a sign of things getting worse. After the game, he overheard his teammates discussing their ability to win with him still playing but some believed he was finished. This affected him deeply and he spent the night speaking with his wife about whether or not he should stop playing. He was no longer getting satisfaction out of playing seeing as he was hurting the team. He had always said that he would stop playing when he was no longer helping. After wrestling with the decision to continue playing or stop while traveling with the team to Detroit, he called Joe McCarthy on the morning of May 2 telling him he was going to quit. McCarthy told him he should just take a little time off rather than quit entirely.

On May 2, 1939, for the first time in 2,130 games, Lou Gehrig was not in the starting lineup and did not play at all. This shocked the umpire who viewed the lineup card brought out by Gehrig himself along with the crowd on hand who had heard the news from the announcer. The benching brought about two articles in the next day’s New York Times, both of which took a different spin on Gehrig’s future. One writer stated that he voluntarily did not play because he became aware of his competitive decline as he was no good defensively or hitting. He noted that Gehrig left five runners on base in the previous game and that retirement was not far off. He did believe warmer weather would benefit his tired muscles. The other writer felt that Gehrig needed just one or two days off and would return to his past success. He cited legends such as Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth, still playing well at age 36. In his opinion, Gehrig had been trying too hard in Spring Training and he should be able to play 100 to 120 games that season and 75 the next. He would not be replaced without a good replacement. However, Cobb and Ruth were not playing with ALS or had anywhere near the struggles Gehrig did. Except for a June 12 exhibition game against their Triple A minor league team where Gehrig played three innings before being knocked down by a line drive, he sat on the bench inactive. The Gehrigs traveled to Rochester, Minnesota the day after for an evaluation at the Mayo Clinic. Eleanor believed it was a brain tumor. When they arrived at the clinic and Dr. Harold Habein saw him walk and shook his hand, he knew immediately that he had ALS because his mother had died from it. After a series of tests taking place over the next five days, Lou had been given the official prognosis and submitted it to Joe McCarthy before any information was released to the public. The report stated that he could no longer participate actively in baseball, and Lou officially retired on June 23, 1939, four days after his thirty-sixth birthday.

After retiring, Lou spent the rest of the 1939 regular season traveling with the team as honorary team captain. On July 4, 1939, a special ceremony in-between games of a double-header was held in his honor where he gave his well-known “luckiest man” speech. The Yankees retired his number 4, the first time that any athlete had ever been given such an honor. After the 1939 season, he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame, becoming the first player to do so without having to wait the customary five year period. After his worsening condition led him to no longer be able to travel with the team, he took a job as a parole commissioner for the city of New York. A series of letters written between him, his wife, and his doctor at the Mayo Clinic from July 1939 through just before his death reveal specific details about his condition and how the worse news was kept between Eleanor and Dr. Paul O’Leary. The letters reveal, among many things: he was forced to take large doses of many vitamins, quit smoking, and put his signature on a stamp because writing became too hard for him. Gehrig was completely bedridden by May 1941 and barely able to move, talk, or swallow. He died less than a month later on June 2, 1941 at about 10:00pm.

Lou Gehrig was a courageous and spirited ballplayer who had an undying will to play the game he loved. Along with the advances in ALS brought about by his death, the game of baseball has also changed as a result. Players that have succeeded him are much more careful about conditioning and are more frequently given time to rest and heal. Serious injuries such as the ones Gehrig played through are now treated much more cautiously and the players who suffer them are protected from further injury. Cal Ripken Jr. was able to break his consecutive games streak because he never played with anything more than a minor injury or common cold. He and other all-time greats since Gehrig also have made better judgment about when the right time to quit was. Gehrig’s legacy will live on forever through his many records and also for the health revolution his story has brought about.

Bibliography

I. Guides, Bibliographies, References, and Indexes.

Brundage, Anthony. Going to the Sources: A Guide to Historical Research and Writing. 4th ed. Wheeling, Ill.: Harlan Davidson Inc., 2008.

ProQuest Historical Newspapers New York Times (1851 - 2006). http://www.ezproxy.felician.edu.

Turabian, Kate L. A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations. 7th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

II. Primary Sources

Dawson, James P. “Forced Rest Aids Yanks’ Casualities,” New York Times, 24 May 1938, p. 25.

Dawson, James P. “Gehrig Voluntarily Ends Streak at 2,130 Straight Games.” New York Times, 3 May 1939, p. 28.

Dawson, James P. “Heinrich in Game at Gehrig’s Post; Barrow Observes Work Closely,” New York Times, 23 March 1939, p. 33.

Dawson, James P. "McCarthy, Making Light of Move, Says he Rested Veteran, Who has been far off Form." New York Times, 23 March 1939, p. 33.

Dawson, James P. “Yankees Down Red Sox with Aid of Errors: Dodgers Defeat Phillies in 12th,” New York Times, 30 April 1938, p. 10.

Dawson, James P. "Yankees End Work in Training Camp and are Ready to Start Road Trip Today." New York Times, 30 March 1939, p. 30.

Drebinger, John. “McCarthy Expects Yanks to Win Again.” New York Times, 2 February 1939, p. 28.

“Gehrig, the ‘Iron Man’ of Baseball, Now Looks Ahead to 2500 Games.” New York Times, 1 June 1938, p. 27.

Gehrig, Eleanor, and Joseph Durso. My Luke and I. New York: Crowell Publishing, 1976.

Gehrig, Lou to Dr. Paul O’Leary, 17 February 1940, Rip Van Winkle Foundation.

Kieran, John. "The McCarthy Method of Training." New York Times, 21 March 1939, p. 34.

Kieran, John. "On Letting Those Yankees Alone." New York Times, 13 March 1939, p. 24.

O’ Leary, Paul to Lou Gehrig, 30 November 1939, Rip Van Winkle Foundation.

Schloss, Walter. 1939. Letter to the editor. New York Times. March 26.

III. Secondary Sources

The ALS Association. "What is ALS." http://www.alsa.org/als/ (27 February 2010).

Cavicke, Dana, and Patrick O'Leary. "Lou Gehrig's Death." The American Surgeon 67, no. 4 (2001): 393-395.

Davis, J.H. "Fixing the Standard of Care: Motivated Athletes and Medical Malpractice." American Journal of Trial Advocacy 12 (1988): 215.

Eig, Jonathon. Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2005.

Friend, Harold. "Lou Gehrig's Salary Cut." Suite 101. http://major-league-baseball.suite101.com/article.cfm/lou_gehrigs_salary_cut (12 March 2010).

Greenberger, Robert. Baseball Hall of Famers: Lou Gehrig. New York: Rosen Publishing Group, 2004.

Kashatus, William C. Lou Gehrig: A Biography. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2004.

Trinklein, Rhaya. Rip Van Winkle Foundation. http://www.lougehrig.com/ (16 September 2009).

Viola, Kevin. Sports Heroes and Legends: Lou Gehrig. Minneapolis: Lerner Publications Company, 2005.

1 Kevin Viola, Sports Heroes and Legends: Lou Gehrig (Minneapolis, MN: Lerner Publications Company,2005), 90.

2 The ALS Association, “What is ALS,” October 2008, accessed 27 February 2010, available from http://www.alsa.org/als/.

3 Viola, 94.

4 Gehrig, Eleanor, and Joseph Durso, My Luke and I (New York, NY: Crowell Publishing, 1976), 9.

5 Viola, Ibid, 94.

6 The ALS Association, “What is ALS”

7Rhaya Trinklein, “Lou Gehrig: The Official Website, Achievements section,” 30 September 2003, accessed 12 September 2009; available from http://www.lougehrig.com/about/achievements.htm; Internet.

8 Ibid, “Awards section,” accessed 23 February 2010; available from http://www.lougehrig.com/about/awards.htm; Internet.

9 Gehrig and Durso, 201-203.

10 J.H. Davis, “Fixing the Standard of Care: Motivated Athletes and Medical Malpractice,” American Journal of Trial Advocacy 215 (1988): 12.

11 Viola, 77.

12 Jonathon Eig, Luckiest Man: The Life and Death of Lou Gehrig (New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 2005), 248.

13 James P. Dawson, “Yankees Down Red Sox with Aid of Errors: Dodgers Defeat Phillies in 12th,” New York Times, April 30, 1938, 10.

14 Robert Greenberger, Baseball Hall of Famers: Lou Gehrig (New York, NY: Rosen Publishing Group, 2004), 75.

15 Eig, 250.

16 Dawson, “Forced Rest Aids Yanks’ Casualities,” New York Times, May 24, 1938, 25.

17 Ibid, 252.

18 Gehrig and Durso, 206-207.

19 “Gehrig, the ‘Iron Man’ of Baseball, Now Looks Ahead to 2500 Games,” New York Times, June 1, 1938, 27.

20 Eig, 252-257.

21 Ibid, 254.

22 Greenberger, 75.

23 Gehrig and Durso, 4.

24 William C. Kashatus, Lou Gehrig: A Biography (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2004), 85.

25 Dana Cavicke and J. Patrick O’Leary, “Lou Gehrig’s Death,” American Surgeon 67 (April 2001): 393.

26 Rhaya Trinklein, “Lou Gehrig: The Official Website, Biography section,” 30 September 2003, accessed 10 March 2010; available from http://www.lougehrig.com/about/bio.htm; Internet.

27 Greenberger, 76

28 John Drebinger, “McCarthy Expects Yanks to Win Again,” New York Times, February 2, 1939, 28.

29 John Kieran, “On Letting Those Yankees Alone,” New York Times, March 13, 1939, 24.

30 Kashatus, 85.

31 James P. Dawson, “Yankees End Work in Training Camp and are Ready to Start Road Trip Today,” New York Times, March 30, 1939, 30.

32 John Kieran, “The McCarthy Method of Training,” New York Times, March 21, 1939, 34.

33 James P. Dawson, “Heinrich in Game at Gehrig’s Post; Barrow Observes Work Closely,” New York Times, March 23, 1939, 33.

34 New York Times, March 21, 1939, 34.

35 Walter Schloss, Letter to the editor, New York Times, March 26, 1939.

36 Greenberger, 77.

37 Harold Friend, “Lou Gehrig’s Salary Cut,” 2 November 2007, accessed 12 March 2010, available from http://major-league-baseball.suite101.com/article.cfm/lou_gehrigs_salary_cut; Internet

38 Kashatus, 86.

39 William C. Kashatus, 87.

40 James P. Dawson, “Gehrig Voluntarily Ends Streak at 2,130 Straight Ganes,” New York Times, May 3, 1939, 28.

41 John Kieran, “A Halt for the Iron Horse,” New York Times, May 3, 1939, 31.

42 Cavicke and O’Leary, 394.

43 Gehrig and Durso, 11-12.

44 Rhaya Trinklein, “Lou Gehrig: The Official Website, Achievements section”

45 Ibid, “Lou Gehrig’s Death,” 395.

46 Ibid, 395.