Donald Campbell - waterspeed record 4th January 1967

Waterspeed record

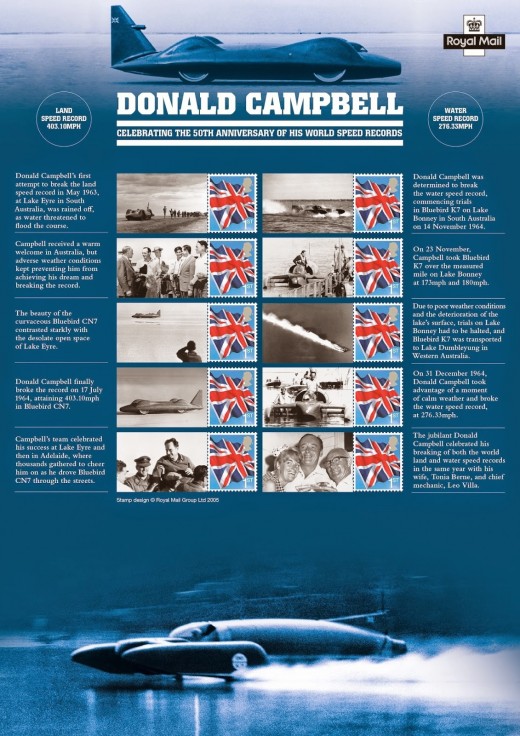

Donald Campbell was the only man ever to achieve both land and water speed records in the same year. In total he achieved eight speed records over nine years. For two whole months engine problems and bad weather had prevented Campbell from achieving the record. A new engine had been installed after early test trials had destroyed the previous engine. Eventually the bad weather cleared a record attempt was now inevitable.

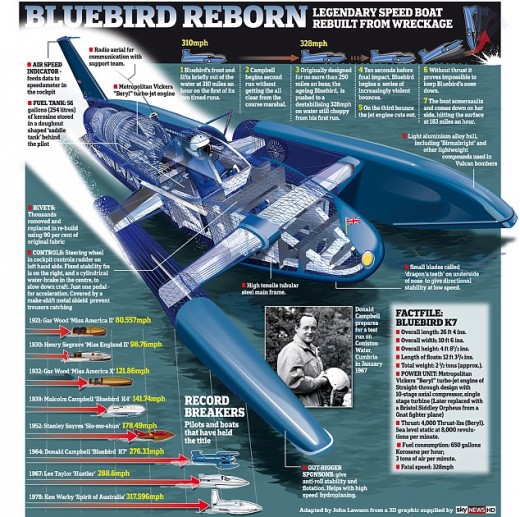

Bluebird was a hydroplane designed and built by the Norris Brothers specifically for Campbell to achieve his dream of breaking the water speed record. Most racing boats were driven by propellers, Ken Norris’s solution was to fit a jet engine which would increase the propulsion to 200 mph. Campbell had already achieved his dream of breaking 276.33 mph on water, however he wanted to keep the record out of reach from the American’s whom he believed would take it from him. His sponsors had deserted him, but if he could break the water speed record again, he might get the funding he needed to build a rocket car and break the Land Speed record. The press turned their backs on him; critics thought that after 13 years the BlueBird craft would struggle breaking the next record. Instead of focusing on the negativity around him, Campbell a determined man like his father set his sights on achieving 300mph at Coniston Lake.

On a cold Wednesday morning on the 4 th January 1967, at 8:40 am, Campbell climbed into the BlueBird K7. It was a cold morning as the safety checks had already been carried out on the craft; spectators were lining up the banks of Coniston Lake, North England, to watch Donald Campbell many whom regarded him as a household name. Placing on his Helmut on and built in microphone he pulled the windscreen above his driving seat. Turning on the jet engine he proceeded to build up pace, Bluebird was once again speeding across the water. In order to break the record he had to make two runs in both directions according to the Swiss time keepers present that day. Campbell put his foot to the ground as BlueBird gained momentum across the lake. The safety team observing Bluebird kept in radio contact with Campbell as he attempted to accelerate passed 297 mph. So far everything was going well for Campbell overall. Bluebird had originally been fitted with a 200 mph engine, so with a faster engine Bluebird was now entering into the unknown. The course marshal gave the all clear for Campbell to make his second run, circling he began his return. Determined to push BlueBird even further he accelerated to the absolute limit on his second run. It was becoming evident to the safety team that Campbell was finding it difficult “I’ve got the bows out, I’m going out uhh”. Again reaching 310 mph, Bluebird’s head started to lift out of the water, for half a second it was airborne. Its engine cut out, flying 50 feet into the air, and then flipping over somersaulting then crashing into the water severing into two as it shattered in the water. Silence and horror descended amongst the spectators and a shocked safety team who had lost radio contact with Campbell. Bluebird was sinking fast to the bottom of the Coniston water; Police and Royal Navy drivers were dispatched, however after a long search of Coniston Lake neither Bluebird nor Campbell’s body were ever found.

Campbell was awarded a CBE and a plague was unveiled close to Coniston Lake.

34 Years Later

Bill Smith, an amateur diver from North Shields and owner of Newcastle engineering factory, headed up a team of volunteers and set out to search for the wreck of BlueBird at Coniston Lake. “We knew he went in with Bluebird and never came out”. Coniston Lake is 40 metres deep, so no one could be exactly sure were the wreck was or if she had sunk in the mud. After spending a considerable amount of time studying old film footage of Bluebird’s crash, he and the rest of the team repeatedly tried to look for clues. However even after pinpointing a rough area where BlueBird might have crashed left a huge area of the Lake to search. Smith and his team used the latest sonar and underwater cameras to search the entire lake to find the wreckage. It would be a painstaking task for Smith, which would take months and months of searching.

In October 2000, late at night Smith’s sonar spotted a large man made wreckage which he had not seen in Coniston before. He had found what he thought was the Bluebird wreckage, only a dive could confirm if he had actually found it. “I’ll never forget the first time I saw the Bluebird. “I’d only ever seen black and white photos and, as I shone the torch in the murky waters, I was struck for the first time that she was actually blue. “When we later saw that iconic British flag on the tail fin it was amazing. To fire up her engines once more shows the commitment of everyone involved.”

He contacted one of Campbell’s children, Gina Campbell who gave her consent to raising the wreckage from the dark depths of the lake. After re-assembling some scattered debris, Smith along with Steve Moss an accident investigator tried to determine the cause of the accident. Moss came to conclusion Campbell had time to apply the accident emergency brake on before crashing, indicating he must have known something was wrong however BlueBird did not crash into the water head on. The craft was hit by a massive side-ways blow. Which might explain why Campbell’s body wasn’t found anywhere near BlueBird. Norris believed the up and down sponsons from the Campbell’s first run lifted the nose of the boat out of the water. After Bluebird was lifted out of the Lake and transported to land, restoration began the engine had to be drained of water. Accessing the wreck also provided some ideas for the whereabouts of Campbell’s body.

Three months, on 26th May 2001, close to the crash site, 200 feet in 140 feet of water, again after using sonar Smith found Campbell’s body. The only way to defiantly confirm if it was Campbell was to make dive into the depths of the lake. The following day “We placed his body in a casket underwater and then lifted it ashore. It was a very emotional moment for every one present.” A funeral for Campbell was held at Coniston Cemetery close to St Andrew’s Church.

Search for BlueBird

The restoration project

For the past 16 years Smith and team of engineers have rebuilt BlueBird piece by piece, the lack of funding has been difficult task for everyone involved in the restoration. BlueBird was built with a 1967 Bristol engine, light aluminum alloy hull and small parts all of which had to be redesigned as they were now out of production.

The Lake District has given permission for early test trials of the newly built K7 Bluebird in 2017, after which the craft will go on display at the Ruskin Museum.