Currency Markets - Part Two

Gold Standard Under Threat

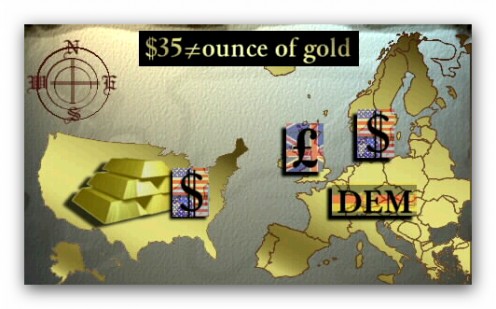

In the early 1960’s the diverging interests of member nations continued to put strain on the Bretton Woods agreement. Germany remembering the hyper-inflation of the 1920’s was very conservative in its monetary policies. Britain and the US embarked on great social experiments leading to bigger governmental borrowings. Pressure increased on the dollar and the pound sterling versus the value of gold. The US government made many attempts to stabilize the dollar gold price at $35 an ounce. In 1963 the US introduced the Interest Equalisation Tax which was an attempt to keep dollars in the United States and slow the demand on US gold reserves.

The Eurodollar Market

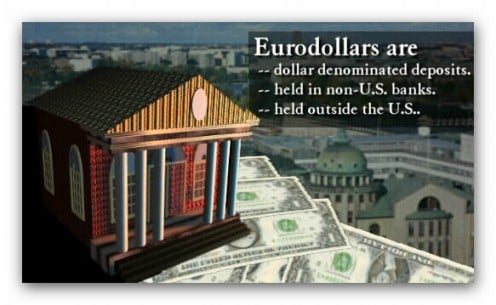

Another attempt was made in 1965 through the Voluntary Credit Restraint Program which controlled lending to US multinationals for foreign investments. These new US regulations created the need for an unregulated market in dollars outside the US. These events led to the development of the Eurodollar market and Eurodollar trading. Eurodollars are US dollars held in non-US banks outside the United States. Since the dollars are outside the United States they are not regulated by US banking laws. Just like corporate bonds which have a higher yield than treasury bonds because they reflect a higher risk, so Eurodollars because they were not backed by government guarantees, or not regulated by any government body, or not required to have reserves and can be fully invested, attracted a higher yield due to the risk premium they bore.

The Eurodollar market became the basis for the dollar forex forwards and forex swaps and forex options market. Without the liquidity of these Eurocurrency markets it would have been impossible for modern day commerce to trade as we know it today.

Bretton Woods Begins to Fall Apart

In 1967 succumbing to the pressures from the diverging policies of the International Monetary Fund, Britain devalued the pound from $2.80 to $2.40. This increased demand for the dollar and put further pressure on the dollar price of gold which was still at $35 an ounce. In 1968 a two tier system of prices was introduces. Between countries and central banks gold was exchanged at $35 an ounce. However, in the markets gold and the dollar were left to the forces of supply and demand to dictate the prices. As you can imagine by the end of the 1960’s the fabric of the Bretton Woods system was falling apart as governments tried to regulate the markets within the framework of the accord.

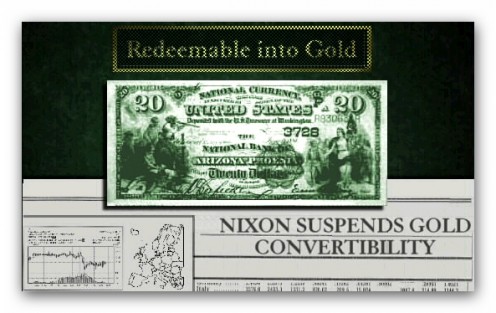

Era of Fixed Exchange Rates Against the Dollar Ends

In 1971 the German central bank tried to intervene in the forex markets to support the flagging dollar. For several weeks it sold Deutsche Marks and bought dollars but in the end the pressure was too much and the German mark was allowed to revalue against the dollar. In August 1971 President Nixon suspended convertibility of dollars into gold. He also imposed a tax on all imports. The tax was only in force for a short time but it signalled to the forex markets that a devaluation of the dollar was due. In late 1971 in a last ditch effort to save Bretton Woods the International Monetary Fund members met in the Smithsonian Institute and the so called Smithsonian agreement was reached.

The official price of gold was set at $38 an ounce and the intervention bands were widened from 1% between currencies to 2.25% between currencies in the EEC. At the beginning of 1973 the dollar became under pressure again despite the efforts of the German central bank in the forex markets. On February 12th the forex markets were closed and the dollar was devalued by 10%. In the following weeks the dollar was allowed to float freely against the other currencies. The era of fixed exchange rates against the dollar had ended.

A Single Currency in Europe

One aspect of the Bretton Woods agreement remained in place however. The members of the European Economic Union agreed to continue to have their currencies move within a narrow band against each other, while they floated against the dollar and other major currencies such as the Yen and the Swiss Franc. Their thinking being that eventually within the European Economic Community there would be one single currency.

Much like the individual states in the US the member states of the EEC were asked to form common bonds to lower trade barriers and link their currencies. The EEC countries currencies were allowed to fluctuate within a 1.125% band, while they were allowed to fluctuate within a wider band of 2.25% against other major forex currencies. This arrangement was called ‘Snake in the Tunnel’. This system lasted from the spring of 1972 until the spring of 1973 when the EEC currencies became unlinked with the dollar. The ‘snake’ continued for a short while within the EEC currencies but eventually that too was disbanded as the countries found it increasingly difficult to make the economic sacrifices necessary to keep their currencies in a tight band.

European Monetary System

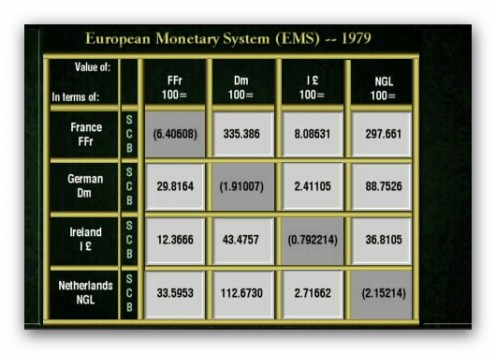

In 1979 the European Monetary System (EMS) was formed. It represented a further attempt at European economic coordination. A grid was established linking the values of each currency to each other. The maximum divergence that was allowed was 2.25% for the strong currencies and 6% for the weaker ones. Divergence beyond these boundaries required that the central banks of each country intervene in the forex markets by buying the weak currencies and selling the strong currency to maintain their relative values.

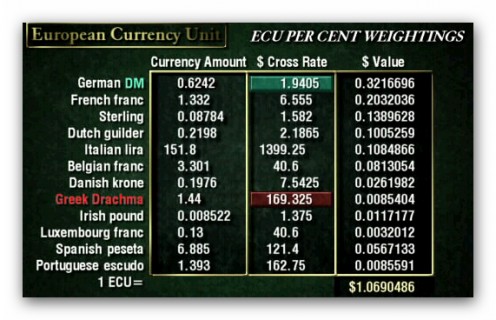

The ECU, The European Currency Unit was also introduced in an attempt to create a single European currency. The ECU is a currency based on a weighted average of the currencies of the Common Market. The ECU also serves to provide a relative value for each currency in the EMS. An active market in ECU denominated bonds, a liquid spot market and forward forex market was developed. The primary activity of these markets was to supply liquidity through speculative trading and arbitrage on the component elements of the ECU unit. All such trading activity serves to stabilize the currency and interest markets and is therefore valuable. Throughout the 1980’s the EMS suffered occasional periods of stress in the system with speculative runs on weak members in the system resulting in frequent realignments. The German central banks anti-inflationary conservative monetary policies were out of step with the more inflation prone easy money policies of France, Spain, Italy and the Scandinavian countries.

The Maastricht Treaty

Until recently monetary authorities in the western world assumed they could control currency values via legislation and that government authorities could bring together all the disparate economic interests in Europe. The Maastricht Treaty proposed that a single European central bank be established much as the Federal Reserve was established in 1913 to act on behalf of the United States. After the European currencies were fixed they would be moved into a single currency. Over a period of years the individual countries of Europe would gradually cede their autonomy to a centralized entity creating a united Europe. The treaty details a series of steps each country must take and terms it must adhere to leading to monetary union by 1999. The process of ratifying the agreement however displayed a few of its flaws. Few countries wanted to give up the required degree of their sovereignty. The Danish people at first rejected it and caused panic in the EMS. They accepted it later however. Britain accepted it but a popular vote was never taken for fear of being rejected. Acceptance by the British has been only with special conditions which allow it to opt out of certain requirements in the future. In 1992 the EMS came under intense pressure and in September Britain was forced out of the European Rate Mechanism after less than two years as a member. German tight money policy was incompatible with most of the other members of the EMS and one by one they devalued or left the system.

Over December 1992 and throughout 1993 speculators proved many times over that the market in foreign exchange was far more potent a force in driving forex rate policy than central banks. One of the most famous examples of speculation driving economic policy occurred when George Sorros was reputed to have earned over 1 billion dollars selling British Pounds and buying dollars and German marks betting against the central banks ability to withstand market forces. In August of 1993 the European Rate Mechanism intervention points were widened to 15% for most currencies. An admission by the central banks to the forex markets of their inability to dictate exchange rates speculators made fortunes in forex trading betting against central banks capacity to manage forex exchange rates which was in contradiction of the policies and diverging economies of the European Monetary System members.

Speculators and Volatility

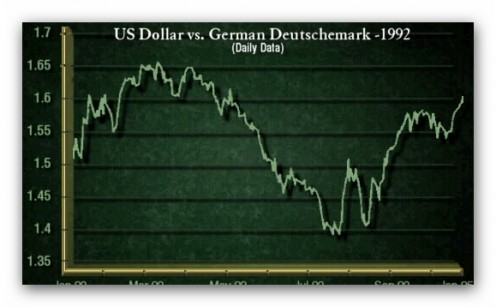

Currency volatility has in itself been volatile. There have been periods of relative calm and short periods of high volatility. This can be seen in this graph which shows the dollar deutschmark relationship in 1992. The dollar reached a high of 1.65 in March and by September it was at a low of 1.40.

Speculation and speculators have been blamed for a lot of this volatility. However, the truth is that speculators increase the volume of trading and provide the capital that keep the foreign exchange markets liquid and provides an important economic function in the market place. The more speculators take profits from the market the more liquid and the more stable the forex markets tend to become. Periods of volatility are always associated with speculation as the market tries to find equilibrium value for each currency that reflects all of the information for that currency in the market place. In fact in some cases speculation on one currency has led to economic reform in the country of the currency.

In January 2002 the Euro became legal tender for twelve of the twenty seven EEC countries and replaced their old national currencies. Now in 2011 seventeen of the twenty seven countries are members of the European Union and use the euro. These are Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, The Netherlands, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Estonia and Spain. Other European countries are slated to adopt the Euro in 2012. Of the original members of the EEC Britain and Denmark still haven’t adopted the Euro.