Aristotle's Ethics and the Summum Bonum

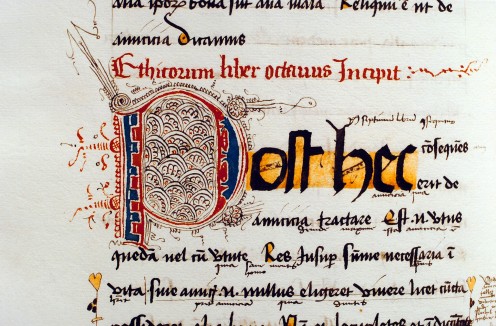

Aristotle's Ethics: Illuminated Manuscript

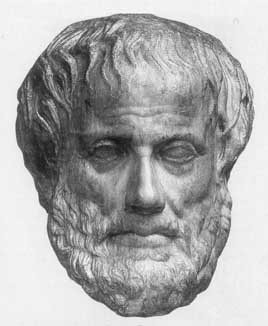

As I mentioned in my hub on the Metaphysics, Aristotle is a friend of common sense or consensus (endoxa). He believed this to be a valid starting point for deeper inquiries into the human condition. And so, Aristotle starts his Nichomachian Ethics, with the common sense assumption that "every art, inquiry, action and pursuit aims at some good or end." If our actions are not aimed at some end or had no purpose, they would necessarily be done at random as a madman would. Aristotle's concern in this work is to develop a normative philosophy in the sense that his concern is about the norm and not deviations from the norm--thus, when Aristotle makes use of universals like "every" and "all", he implicitly acknowledges exceptions to the norm, like madmen. Aristotle's normative approach is also a function of the teleological method that underlies all of Aristotle's thought. This is why Aristotle is so concerned with "aims" or "ends" or "end goals." The ancient Greek word that encompases these is "telos" whence we derive the word "teleological." In addition to looking toward ends and aims, teleology is also a forward-looking principle of causality insofar as the things desired or goals sought propel entities to action. This is to be contrasted with mechanical or "efficient" causation which is the backward-looking causality which preoccupies the so-called "hard sciences." It is important to keep in mind Aristotle's teleological orientation when we encounter his arguments.

Aristotle starts off by stating that some "ends" (teloi) are sought for the sake of something else, and other ends are sought for their own sake or are ends unto themselves. Aristotle considers money and power as examples of ends that are sought for the sake of something else. They are, in the words of Aristotle, "merely useful" in pursing something further. Those ends which are sought in virtue of themselves, in whole or in part, include honor, pleasure, having a virtuous character, and "happiness" (eudaimonia). Aristotle writes, "Will not the knowledge of [eudaimonia], then have a great influence on life? Shall we not, like the archers who have a mark to aim at, be more likely to hit upon what is right?"

In the abstract, Aristotle's proof for the summum bonum runs something like this: An objective A is more perfect than another objective B when A is worth pursing for its own sake and B is not, or if both are worth pursuing for their own sakes, when A is not pursued for the sake of something else, and B is. According to Aristotle, the only good which seems to be pursued for its own sake and not for the sake of something else is eudaimonia, a peculiarly Aristotlian version of "happiness".

Before developing his own thought on this matter, Aristotle briefly reviews other common perspectives as to what constitutes happiness:

"Let us begin again from common beliefs ("endoxa")...for it would seem, people quite reasonablely reach their conception of the good, i.e. eudaimonia, from the sort of lives they lead; for there are roughly three lifestyles that form the template according to which people order their lives and seek happiness...

"The many ("hoi polloi"), and the most vulgar, would seem to conceive the good and happiness as pleasure being the ultimate good, and hence they also pursue luxuries and physical gratification. Such ones appear completely slavish since the life they decide on is a life fit for grazing animals; and yet they do admittedly have some arguments in their defense.

"A more cultivated group of people, those active in politics or professionals, conceive the good as honor and approval, since this is more or less the end normally pursued by such ones. This, however, appears to be too suprficial to be what we are seeking, since it seems to depend more on those who honor than on the one honored, whereas we intuitively believe that the good is something of our own and hard to take from us.

The third [template] is the life devoted to philosophy, which we will examine in the foregoing."

Generally speaking, eudaimonia can be translated as a combination of blessedness, happines, prosperity, success and flourishing. It is a state of doing well and being well in doing well. In the context of Aristotle's teleology, eudaimonia is also the fulfillment of ones human nature or telos. Aristotle proceeds to consider different templates of human fulfillment. He demonstrates that pleasure, honor and even being virtuous, though desirable in themselves, are ultimately pursued for the sake of something else, and that that something else is eudaimonia. "Eudaimonia, on the other hand, no one chooses for the sake of these, nor in general, for anything other than itself." In addition, Aristotle considers eudaimonia to include a sort of self-sufficiency. It offers us the only true fulfullment that life can provide, and "which when isolated makes life desirable and lacking in nothing."

Aristotle continues, "Presumably, however, to say that happiness is the chief good seems a platitude, and a clearer account is still necessary. This might perhaps be given, if we could first ascertain the function ("ergon") of man." Here Aristotle articulates the so-called "ergon argument", an argument based on man's function. Aristotle analogizes, "For just as a flute-player, a sculptor, or any artist and all things that, generally speaking, have a function or activity, 'the good' and 'the well' is thought to reside in the function, so would it seem to be for man if he has a function." This argument is typical of Aristotle's teleological method--a method that is concerned with functions and ends.

Human beings, like the member of all other species, have a specific nature; and that nature is such that they have certain aims or goals, such that they move by nature (kata physei) towards a specific end (telos). Aristotle's metaphysical biology, as articulated in his Physics, is implicated in these statements insofar as he believes a normally function human being is designed by nature to find its happiness in a certain kind of "being and doing." To make an analogy from a biological perspective, the telos of an acorn is the fulfillment of said acorn, to wit, a fully flourishing oak tree. This telos is actually a built in biological principle within the acorn and to the extent the acorn fully develops into a fully flourishing oak tree is the extent to which that acorn could be considered to have fulfilled its telos or achieved its peculiar sort of "eudaimonia." This image of a fully florishing oak tree is the universal template into which all acorns must grow and to the extent that a particular acorn deviates from this norm is the extent to which the acorn can properly be considered a "failure." The same analogy applies to human beings. Like the acorn, the developing human being has a course of development that seeks its fulfillment in a certain way of being and doing. To the extent that a particular human being deviates from this norm is the extent to which it can been deemed a failure.

The key to discovering that happiness which is uniquely human comes from identifying those functions that are uniquely human (i.e. functions not shared with animals, plants or minerals). This uniquely human function is, according to Aristotle, rationality or "the rational principle." Aristotle states that the function of man is an activity of soul which follows or implies rationality, and the function of a good and noble man finds it fulfillment in the good and noble performance of this uniquely human faculty. And so the best way for man to achieve happines, according to Aristotle, is to make good use of his rationality or human reason, and its proper functioning is a prerequisite for a man to do well in life. It is through reason, or rationality, that one discerns and chooses what is best in particular circumstances, and it is by means of reason that one comes to a general knowledge of what is best.

Now the next step in Aristotle's inquiry is to address the following: If the function of man is an activity of soul which follows a rational principle, and the function of an excellent man is following excellently that rational principle, what then is required for a man to exercise this rational principle well? Aristotle's answer is the virtues (e.g. good judgment, honesty, moderation, courage, friendship and generally discerning the "golden mean" with regard to ones behavior). Aristotle treats of the specific virtues later in the Ethics, and indeed Aristotle's ethical system is classified as a "virtue ethics" (as opposed to a deontological system or a utilitarian system of ethics).

Other powers which are a part of our nature, like reproduction, growth, nutrition, pursuing pleasure and avoiding pain, are functions which humans share with the lower animals, and so the fulfullment of these faculties, though being a part of our nature, are not uniquely human and are not sufficient for the fulfillment of the highest good which is unqiue to humans alone.

Thus, eudaimonia entails living ones life in accordance with the virtues under the guidance of reason. Aristotle keenly points out that only after ordering ones soul in such a manner can one truly enjoy life and take pleasure in the right sort of activities. Without this proper inner orientation, the pleasure-seeker or the approval-seeker is incapable of happiness EVEN IF they obtain the pleasure and approval they seek since what they pursue, in addition to being fleeting in nature, does not satisfy what is most deeply and uniquely human within them. In Aristotle's opinion, perhaps not surprisingly, it is the contemplative life of the philosopher that is most apt to bring us that uniquely human happiness he espouses, since it is the philosopher who engages that uniquely human faculty in the most noble manner.

To be fair, Aristotle does grant that life also needs some degree of good fortune in the ordinary sense. It is hard to have a full measure of happiness according to Aristotle, if you are physically ugly, or born to humble circumstances, or disappointed in the development of your children. Regardless, Aristotle's inquiry strongly favors a brand of happiness that is independent, to the greatest extent possible, of the external contingencies of life.