Cognitive Psychology Emotions and Problem Solving

Review the article Inspired by Distraction: Mind Wandering Facilitates Creative Incubation. What was one issue that the experimenters sought to address through their research? How do these results apply to the area of problem-solving and psychology in general? What about other disciplines?

In the article “Inspired by Distraction: Mind Wandering Facilitates Creative Incubation” the experimenters sought to address the issue of mind wandering and creative incubation through their research. The experimenters used an incubation paradigm to evaluate if performance on creative problems can be assisted through the engagement in a demanding task or an undemanding task that take full advantage of mind wandering. In order to test the hypothesis experimenters recruited 35 male and 110 female participants between the ages of 19 to 32 to complete a baseline UUT, incubation, post-incubation UUT, and then a daydreaming frequency IPI. The experimenters found that participants in the undemanding-task condition experienced greater mind wandering than the participants in the demanding-task condition. These results show “that working memory load decreases the frequency of mind wandering” (Baid, Smallwood, Mrazek, Kam, Franklin, & Schooler 2012).

The results of this experiment can be applied both to the areas of problem-solving, psychology, and education fields. The study showed “that taking a break involving an undemanding task improved performance on a classic creativity task (the UUT) far more than did taking a break involving a demanding task, resting, or taking no break(Baid, Smallwood, Mrazek, Kam, Franklin, & Schooler 2012). The results of this study apply to problem-solving and psychology in general by providing new information about how to create a plan that will assist in classic creativity. This information would tell people in education fields that when teaching a student it would be best to give the student a break where he or she will complete an undemanding task in order to facilitate the improved performance of the student. This study could be taken a step further in order to discover if the results were influenced at all by the fact that there were a greater number of female participants than male participants.

References

Ashcraft, M. H. & Radvansky, G. A. (2014) Cognition. (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Baird, B., Smallwood, J., Mrazek, M. D., Kam, J. W. Y., Franklin, M. S., & Schooler, J. W.(2012) Inspired by distraction: Mind wandering facilitates creative incubation. Psychological Science 2012 23:1117. doi: 10.1177/0956797612446024

The Psychological and Neural Processes Involved in Emotion, Pain, Self-Regulation, Self Perception, and Person Perception: Kevin Ochsner

"1. How did you become interested in psychology?

>> I'll give you the short version of the story. I actually started out in college interested in engineering of all things and during my freshman year of college, I took an introductory psychology class that peaked my imagination in a way that engineering classes simply didn't, so simply taking physics and chemistry, computer science and calculus, although I suppose interesting at some level, it's hard for me to imagine that so many years in the past, or I guess now so many years in the future, it was psychology that really captured me and then during my sophomore year I took a class on the brain and the mind and one of the instructors, a woman named Marie Banach [assumed spelling] was teaching the class, I approached her after the class and said hey this is really interesting, I'd like to talk to you about it. She had me write an extra paper for the class and then invited me to be in her lab and if it weren't for Marie Banach I can safely say I would probably not be in psychology because you know a lot of kids in college are shy and I was extremely shy, I was very quiet and I had no idea how to get involved and she got me interested and from there I went to graduate school in psychology and got various bits of training here and there and different disciplines but that I think is the most important part of how I got involved.

2. What is your current area of research?

>> So the work we do in my lab fits broadly within the field of social neuroscience or social cognitive neuroscience, which is an interdisciplinary field that's meant to link two different parent disciplines together, sort of the offspring of two parent disciplines. Social psychology on the one hand, which is concerned with experience and behavior of people in social context and motivations, what it's like to be a person that's making certain kinds of choices, that has social values and motivations and cognitive neuroscience on the other hand, which has been concerned for the last oh I'd say 15 years with the brain bases of basic building blocks of cognition, like memory and attention and language and social neuroscience tries to put those things together and to understand how it is that our feelings, our tendencies to affiliate with others, to cooperate or compete, to be able to control our emotions so that we engage in socially appropriate behavior, all depend upon a basic set of brain systems and so the work we do in social neuroscience is really about two things: One is how you regulate your feelings in a context appropriate way and the other is how can we be empathic and understand others feelings and act appropriate.

3. How well are the fields of social psychology and neuroscience integrated?

>> Well I think that the integration's getting greater and greater and better and better over time. So if you were to have asked me that question six years ago, I would have said it's -- it's on its way, but not there yet. And now I'm -- I'm happy to say that I think the integration has been very effective. So I was just asked here at APS to speak in a symposium on social neuroscience and its application to substance abuse disorders. So not only academics, but funding agencies are taking note of it. And I think there's some increasing recognition that social neuroscience sort of approaches to understanding the brain bases of social and emotional behavior, and then left out of our understanding of lots of clinical disorders for quite a long time. Not that people didn't think it was important, but that there weren't -- wasn't an experimental approach -- a scientific approach to make it possible to link together the neuroscience and the social and emotional stuff. And now building on animal and human research that's come before, we're now at a place where that can happen. And the integration's happening I think more and more all the time. There's more jobs in social neuroscience, there's lots -- some of our best graduate students, when they apply to Columbia, they want to do this kind of research. I think that's probably true at a lot of institutions. And in fact when I teach undergraduate classes, students will say to me wow, a field that finally puts everything together. You know, why was I taking a social psychology class separate from my neuroscience class? They always wanted to understand the relationship, and I think happily for them, and -- and happily for us there's a field whose -- sees its job as trying to do exactly that.

4. What specific questions were you hoping to answer with your research?

>> The work that we've just started doing on substance abuse takes us at starting point the notion that people are motivated to abuse substances because of the emotions of the experience in their everyday life. So sometimes people choose substance to drink alcohol, or use cocaine, methamphetamine, whatever it might be to escape from the stresses and the negative emotions that they can't cope with in everyday experience. And what we're wanting to do -- oh the other thing that might motivate them is the kind of perceived positive hedonic pleasurable value of using the substance, and the social context in which they use the substance. And so what we've been trying to understand is how it is that people can use cognition, or thinking about the value of these drug-related cues, or thinking about the situations that make them feel bad in their everyday life, to turn off those emotional impulses, and limit their desire, their motivation -- excuse me -- to engage in substance abuse.

5. Discuss the brain functions that underlie behaviors and cognitions related to substance abuse and smoking.

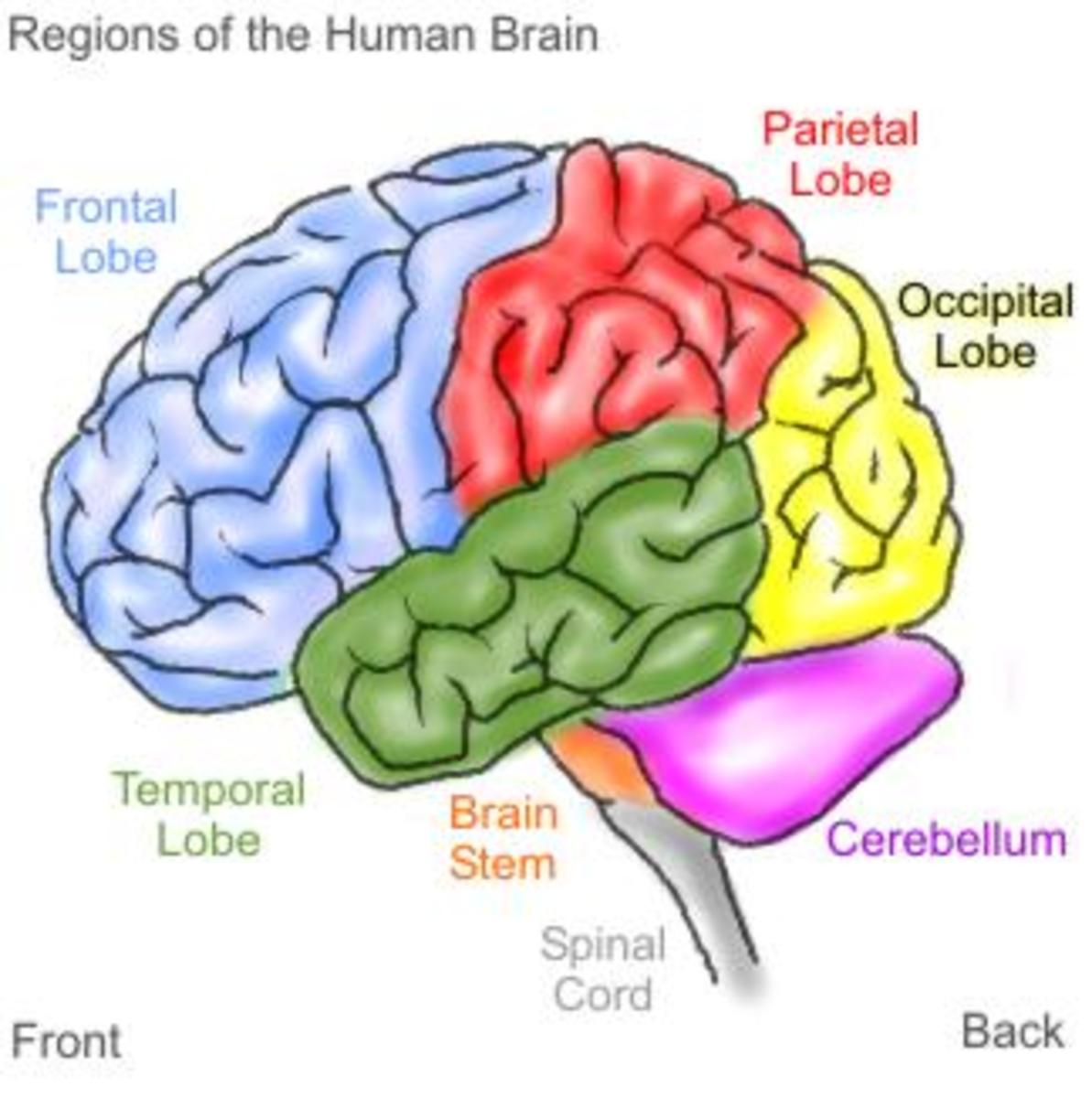

>>And so we have a long term project to study that in people who use methamphetamine. We just started studying it in smokers where... What we're asking smokers to do is to in some cases, think about the short term gain, the short term hedonic sensory pleasure of smoking a cigarette; what it feels like to have the smoke inside your lungs and so on. And other cases to focus on the long term consequences which we really do when we're engaging in substance abuse. And we're looking at how their desire to engage in smoking changes as a result and then the next step of that is going to be to look at what the brain systems are that underlie that ability. And in particular, we're just in dynamics where there are brain structures in your front lobe up here that are important for generating this cognitive reinterpretation of the meaning of...it could be a cigarette as a queue or whatever is making you feel bad that may make you crave a cigarette. And how those prefrontal systems that do the cognitive work interact with brain systems that are often subcortical that turn on your affective impulse to begin with. So brain systems like the amygdala which means "almond" in Latin. It's a little cluster of nuclei buried beneath your temporal lobe. That brain structure seems to be really important for detecting and encoding into memory the things in your everyday life that are really relevant to your goals and that make you feel affectively aroused. And so if it's something negative that makes you feel stressed and crave a cigarette or if it's something that's a queue to the positive social experiences you've had with a cigarette, the amygdala might be sensitive to those queues, turn on essentially, and then we're looking at how you can use prefrontal cortex to turn that off and hopefully in some way curb the impulse.

6. Have you studied relapse as it relates to substance abuse?

>> Yeah, we have not.

>> Okay.

>> Not yet. I mean in the long term, there's -- I do know there's a lot of behavioral research on -- on relapse prevention, but that's a -- it's a down the road goal for us.

7. How is the social cognitive neuroscience approach different from traditional methods?

>>The basic experimental paradigm that we use is one that we can have people do on a computer in a psychology laboratory, and then we can transport it and have them perform the same task while they're in a functional magnetic resonance imaging scanner. And so the limit for doing FMRI research is that you have to have people have a simple task where they can repeat the same thing again and again and again, and generally they interact with a computer. It's the exclusive limit; you can do things other ways, but that's the basic idea. And so what we do in this experiment is take advantage of the fact that pictures often can illicit strong feelings in people. So we show people pictures of other people smoking. So those... Showing a smoker who has been abstinent from smoking for a few hours a picture of someone else smoking often makes them feel like, "Oh, I would really like a cigarette right now." So the basic notion is you show them a photograph like that and you give them the instruction to either focus on how it would feel right now in this moment if you were to have a cigarette and that's the short-term hedonic sensory pleasure, or think about what might happen later; what's the long-term consequence of doing that? So every time I show people a photograph, they get an instruction to focus on now (the immediate consequences) or later (the long-term consequences) and then what we're interested in is how does that change their desire to crave the cigarette? It does pretty effectively. But then the next step is going to be having people complete the computer test in the scanner and measure activity in the brain structures that I mentioned previously.

8. Has anything surprised you in your research?

>> You'll have to stay tuned for that one.

>> Okay.

>> So -- so right now, the research that we're doing in smokers is really our -- our first step away from doing basic science research, to applying our understanding of how effective emotional relation might work in you or me when we're trying to look on the bright side, to understanding how that might be effective or ineffective for different kinds of substance abusing populations. So I suspect there'll be plenty of surprises that await us down the road, and I can't even anticipate what they might be.

9. What is known about motivation for certain behaviors or short-term rewards?

>> Research from folks at NIH, UCLA, lots of places suggest that there's some basic pathways in the brain that involve dopamine -- a particular neurotransmitter -- that seem to be implicated in substance abuse disorders of various kinds. So if you're a -- a methamphetamine abuser, highly related cocaine abuser, cigarette smoking, even alcohol abuse, it seems like there's an important role this dopamanirgic mediated system plays in laying down a habit -- sort of reinforcing the habit that you might have to engage in consumption of the -- the particular substance. So that's one thing that they have in common is this dependence on this kind of common pathway. People sometimes call it a reward pathway, but I think there's other research to suggest that it's really a pathway that's involved in as [inaudible] might say, seeking behavior. So it motivates you to move towards something. In this case it motivates you to want. There's a fellow named Ken Barrage [phonetic] at Michigan that uses this term wanting to distinguish it from liking. Liking is just the pleasure you get from something, but wanting is that motivational sense we have of engaging with it, wanting it, moving towards it. And it seems like that system in the brain that's involved in generating that feeling of wanting is common to various kinds of substance abuse disorders. And so what we're trying to see is whether or not people can use cognitive strat -- or what the neuro bases are of using cognitive strategies to sort of switch off the wanting system. Behavioral work has told us for a long time that you can do that in the moment. And now what we want to do is for the first time image that process of using your thoughts to stop that feeling of wanting in the brain.

10. Have you found any other measurable factors or traits involving emotion that affect brain activity?

>>I can't tell you what our gender story will be, but there will be a gender story. Gender animation [assumed spelling] is a very interesting topic, but I will tell you what I can say. So one thing we've been interested in is how differences and a tendency to ruminate influence the brain systems underlying interactions between cognition and emotion. So as you may know, ruminators are people who tend to focus on negative experiences from their life; often things that made them angry, that were troubling in some way, frustrating, maybe things that made them sad or depressed. And they tend to turn over those events in their mind again and again. They don't gain insight into them. They don't seem to have any personal or psychological distance from them. They just kind of go around and around. But what they may be doing is using in an ineffective way the same kinds of cognitive processes that you could use if you reappraise something to make yourself feel better. Now what we found is that if you measure individual differences and the tendency to ruminate and you correlate that tendency across people with activity in the brain when you're telling people, "Regulate your emotion;" it turns out that ruminators are more effective at modulating activity in brain systems involved in emotion. So if we tell a ruminator, "Turn up your negative emotion by thinking about these images in a way that worsens your feeling," they're amygdala, the structure I mentioned earlier, becomes more activated than someone who doesn't ruminate. But interestingly we might have expected that because you think, "Oh rumination makes people feel bad." But the really surprising thing there was that ruminators were also better at turning off the amygdala. So if we tell people, "Look on the bright side of these images; imagine that sick guy is going to be well. The sad women are just grieving and it's a natural part of a healing process. That guy has an injury but it's really fake; it's just staged." Ruminators were better at turning off their amygdala when doing that as well. So it suggests in some sense that ruminators may have great facility with holding in mind interpretations of an event and using those interpretations to guide their feelings. They just... I sometimes like to say that they tend to only use it for the forces of evil in everyday life rather than the forces of good. One of the important challenges for future research will be to try to understand why is it that somebody who ruminates who has great facility with modulating activity and these emotion systems, doesn't seem to be doing that in the context of everyday life with their personal life experiences"(Ochsner).

The Functions and Consequences of Mixed Emotions: Jeff Larsen

"1. How did you become interested in psychology?

>> Well, you know, all of us spend every day asking questions about people. Why did this person just cut me off? Why did I get an A on this test but a C on this test? And what's real exciting about being a social psychologist is that my job is to ask questions about people, and my training in psychology gives me a more formal way of asking questions about people, and also a -- better tools for actually answering those questions.

2. What is your current area of research?

>> We usually think about good and bad, happy and sad as being polar opposites, and this makes a great deal of sense. If you think of happiness, we smile. You know, the corners of our mouth go up. If we're sad where we frown, the corners of our mouth go down. And also if you think about usually people feel happy or sad and not both. So it, it makes sense to think of happiness and sadness as being opposites, and, in fact, we'd be in good company to think that. Plenty of philosophers and also psychologists have contended that happiness and sadness are polar opposites. Some theories go so far as to say that happiness and sadness are mutually exclusive. If you're happy, you can't be sad and vice versa. A, a, a theory that, that I've been working on, the, the evaluative space model by [inaudible] Gary Bernson argues, instead, that rather than being opposite ends of a, of a single continuum, positive and negative effect represent separatable dimensions. And so from that perspective, rather than thinking of, of, of emotion in terms of a bipolar continuum like this, we think of it in terms of a, a, a two-dimensional space. And what's really interesting about thinking of emotion in those terms is that it raises the possibility that people can feel both happy and sad at the same time. So to, we've been conducting a lot of research to actually test that hypothesis. In one study, we gave people, we surveyed people about their emotions either before or after they saw a film called "Life is Beautiful", which is an unlikely comedy set in a concentration camp of all places, and it has these potentially bittersweet moments. At the end of the film, for instance, the father sacrifices his own life so that his son can survive and be reunited with his mother. And so we thought maybe at the end of such a movie, people would feel both happy and sad at the same time. And so we went in, and after the movie, we asked people do you feel happy, do you feel sad, and sure enough, about half of the people indicated that they did feel both happy and sad whereas people who were surveyed before the film sad no, I'm feeling happy or sad, but very few of them reported feeling both.

3. Can extreme emotions appear at the same time or are they mutually exclusive?

>> First of all, we assume that people rarely experience mixed emotions. It's only in certain emotionally complex situations that people can feel happy and sad at the same time. In a couple of our studies, we have found that college undergraduates are more likely to, to feel mixed emotions when they're moving out of the, their dorms in June than on a typical day on campus. In another study, we found that undergraduates were more likely to experience mixed emotions on their own graduation day than during a more typical day on campus. There's something similar about those situations. Both of them involve transitions. In one case, you're transitioning from the end of your first year of college back to summer vacation, probably going back home and the like. In the other case, it's an even greater transition from the days of college to the rest of your life. And research by some people at Stanford that isn't yet published suggests that it is that transition that is particularly important to experience mixed emotions, and they manage to demonstrate this by conducting an experiment at Stanford in which they surveyed Stanford graduates about their emotions on the day of their own graduation, and they also manipulated with a salience of that transition. Some participants were reminded that, hey, this is your last time that you're going to be here, and then they were instructed, then they were asked to report how they felt, and these participants reported more mixed emotions than other participants who were not reminded that they were in a transitional moment.

4. Is there a developmental stage in childhood during which the ability to simultaneously experience multiple emotions is realized?

>> Previous research from developmental psychology indicates that young children think that people can only feel one emotion at a time, so one child in the study by Stephanie Harder and her colleagues, showed that there was one child who said, I'd have to be two different people to, to be happy and sad at the same time. As children go, grow older thought, they do begin to believe that people can feel happy and sad at the same time, and this has been demonstrated in studies by developmental psychologists, including Stephanie Harder and Donald Westerman [assumed spelling] in which children are read stories about another child who is in an emotionally complex situation. In one story, a child got a new kitten to replace one that had run away, and the, the psychologist then asks the child, how does, how does the child in the story feel, and as kids get older, the more -- they were more likely to say, well, the child feels both happy and sad. What that research doesn't, doesn't investigate is whether there's a similar developmental trajectory, in terms of whether children can actually experience mixed emotions, so my colleagues, Gary Fireman [assumed spelling] and one of my graduate students, Yen To [assumed spelling] and I conducted a study in which we showed children of varying ages a clip from the cartoon, Little Mermaid, and the clip ends with the, the, the Litter Mermaid, Ariel getting married to the love of her life, but unfortunately having to say goodbye to her father forever, and then we ask children, how do you feel? And what we found is that as children grow older, they were more likely to report feeling happy and sad at the same time. This was particularly the case for older girls. For 12- and 13-year-old boys, they were actually less likely to report experiencing mixed emotions, probably because boys just don't care about Little Mermaid as much, as they get older.

5. Can you explain your study involving a situation that might generate mixed emotions?

>> Another study, we had undergraduates play a variety of -- of lotteries, in which sometimes they won the larger of two amounts, and sometimes they won the smaller of two amounts. So on some trials they learned that they have a chance to win 5 dollars or 12 dollars, and then the spinner spun around and it landed on 5 dollars. And the question is how do you feel about this? You've won 5 dollars, but you could have won 12 dollars. Is the glass half empty or half full? Well what the data indicated is that that's the wrong question. The glass is both half full and half empty. Indeed, what we found is the participants reported feeling both good and bad about those outcomes.

6. Can mixed emotions play a role in coping?

>> An interesting finding from health psychology is that when people are dealing with serious traumatic events, for example, loss of a spouse, or cancer, they report surprisingly more positive emotions than one would expect. They certainly report a great deal of negative emotions as well, but also people sometimes report feeling positive emotions. My colleagues and I have suggested that that ability to experience both positive and negative emotions in the face of trauma is important for the ability to cope with that trauma. The, the negative emotions must be dealt with, but in order to deal with those negative emotions, we suspect that one also needs to be able to recognize and, and experience those positive emotions so that they don't simply avoid the stressor all together, that -- those positive emotions allow people to cope with and deal with the stressor.

7. Is there any neurological evidence that supports the claim that mixed emotions can occur?

>> Ah, that's a great question. Not yet. Not yet. Yeah.

8. What does your research reveal about facial expressions?

>> To this point, most of the evidence that people can experience mixed emotions at the same time comes from self report data, and there are a variety of ways that people express their emotions, not just by telling you how they feel. One way that people can express mixed -- one way that people can express emotion is through their face, so for instance, when we, we're happy, we typically smile. When we're sad, we, we typically frown. A really fascinating question for future research is, what is the face of mixed emotions. To what extent when you're feeling mixed emotions do you, for instance, perhaps smile with the lower half of your face, but furrow your brows out of negative affect.

9. What research findings have surprised you most?

>> The most surprising thing about doing this research is how hard it's been to answer the question of whether people can feel happy and sad at the same time. It seems like a relatively straight forward question. And in fact when I ask undergraduates can people feel happy and sad at the same time, they often look at me as if it's a silly question. Of course the answer's yes. And I -- I think about -- over 90% of undergraduates think that people can feel happy and sad at the same time. But when it comes to answering that question from a scientific perspective, there are -- there is a great deal of complexity that comes up. So for instance, in most of our research, we have simply asked people do you feel happy? Do you feel sad? And if they say yes to both questions, we take that as evidence that they're feeling happy and sad at the same time. But there are other possibilities. One possibility is that rather than feeling happy and sad at the same time, people vacillate between feelings of happiness and sadness so quickly, that when we ask them how they feel, they end up reporting both, even if they never felt both. And so we've been addressing that hypothesis lately by conducting studies in which we hand people [inaudible], we -- well before we do that, we -- we bring people into the lab for a study on what they think is about foreign language comprehension. And we then show them one of two clips from the film Life is Beautiful. One has very potentially bittersweet scenes, the other does not. And we told them that emotions can affect language comprehension, and so we need to keep track of how you're feeling during the film. And then we hand them a computer mouse, which of course has two buttons, and we ask them to hold it in their two hands, and whenever they feel happy press the left button, whenever they feel sad press the right button. And if you feel both happy and sad at the same time press both buttons. And what we find is that during those bittersweet moments of the film, when the -- the father sacrifices himself to save his son for instance, people often press both buttons, and tell us that they're feeling both happy and sad at the same time"(Larsen).

The Regulation of Emotion by Social Processes: James Coan

"1. How did you become interested in psychology?

>> I decided to pursue a career in psychology in part by accident at first. I was originally a pre-med student, well, sort of, at the University of Washington, and I took a course in cognitive psychology from Beth Loftus and did an extra credit assignment in that class that wound up being called, "The Lost in the Shopping Mall Experiment," and that wound up being kind of a big deal at the time and so that sort of launched my career in research psychology. I started working with Beth at the time and I went through and did an honor's project with her and then worked with John Gottman for a few years also at the University of Washington and then I was just sort of hooked. So after that I decided to stick with it and go on to graduate school and the rest is me now.

2. What is your current area of research?

>> My area of research has to do with the regulation of emotion by social processes. So, how do when two individuals are together and one of them is stressed out, how does the other help them calm down? And in particular, I'm interested in looking at how that is mediated, how those kinds of social, emotion regulation processes are mediated by the brain so we do, we use measures like EEG and FMRI to look at specific brain processes related to the regulation of emotion in social contexts. We also do a lot of behavioral coding and watching couples interact with each other and hold hands and all that kind of thing.

3. What specific questions regarding stress and social support were you hoping to answer with your research?

>> Emotion is tied to health and well-being in a number of ways. Well-being is obvious in the sense that you know, if you're having an unpleasant time, it's low well-being, right? But it's not so obvious with health. Emotions affect health through the release of stress hormones and things like that that have a negative impact on immune functioning and tissue repair and things like that. And what you find out is that the degree to which you can regulate your stress, you know, keep yourself from engaging in long term stress or lots of intense stress, corresponds to a higher level of health by virtue of reducing the amount of stress hormones in your body. What we've been finding, what people have known for a long time is that having a significant other or having a fairly large number of friends, having social support keeps your level of stress hormones at a relative minimum and that enhances your health. What people haven't known for a long time is how the brain makes things happen. And so we've been doing a series of studies where we put people in the MRI scanner and we put them under threat of electric shock, create stress and then we have them either go through that while alone or holding the hand of a loved one or holding the hand of a stranger and what we find is that any hand holding causes the brain to work a little less hard, but spouse hand holding or significant other hand holding has a big effect on reducing the amount of activity that the brain has in response to threats. And one of the regions of the brain that's particularly impacted here that's also sensitive to how, the quality of the relationship that you have with the person whose hand you're holding, is the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus is already known to be the sort of beginning point or it's called the HPA axis, this cascade of chemicals, hormones that are released into your body that are known to have this negative impact on your health. So we are actually modeling the reduction of hypothalamus activity as a function of holding the hand of a close loved one, while you're under threat.

4. How did you encourage people to volunteer, and what did you find to be true regarding your participants?

>> For things like the handling study with the, with the threat of shock, you know, it's not always easy to get participants to, to, to come in. But we, we typically just put an ad in the paper, and we, we screen them, we interview them. We, we do pay them, sometimes a pretty significant amount, so they, they get some remuneration, but really, I think people are pretty open to volunteering for these kinds of things. A lot of times you find they're actually genuinely interested in it, and I'd want to say that I think generally speaking, we owe these people a great deal for their, for their, for volunteering in these ways because they, they are really our collaborators in all, in all of this. And I think the extent to which you can help them to feel like collaborators instead of just, you know, raw material that you're running through the lab, I think that, that also helps them feel like, you know, more engaged and want to do it.

5. How can holding hands act to regulate emotions? Does the participants’ relationship make a difference?

>>We expected that hand holding would decrease threat related activity in the brain so what we did is we initially recruited couples that were happy so we didn't necessarily expect the quality of the relationship to covary with these neural activations in the brain but it did. It turned out to matter a lot and in some very key regions of the brain. So for example, the quality of the relationship determined how much of a regulatory effect you had on things like the hypothalamus which is responsible for releasing stress hormones and also very enticingly on a region of the brain called the right anterior insula, which is, some people believe is at least partly responsible for your subjective experience of pain. So that gave us some hint that among couples in the very happiest relationships, hand holding, just hand holding, might have functioned as a kind of analgesic like a painkiller.

6. Have you experimented with the effects of other bonding behaviors, beyond hand-holding?

>>At this point we haven't really expanded beyond hand holding and partly that's a function of the FMRI environment. You know people are in this little tube, you know, they're sort of scrunched up and you know they can't move and it's really hard to have any kind of interactions at all so we figured out that at some point we could have people reach into the tube where they were and actually hold hands and that would be one way we could deliver some kind of, you know, supportive central contact.

7. What larger questions might be answered based on these results? For example, can bonding and soothing behaviors act as buggers for serious life stressors and adversities, such as terminal illness?

>>So one of the things that we get asked a lot is, you know, imagine people are suffering from terminal illness or something, some really major stressor, can these kind of things have an impact? We haven't of course you know looked that directly with our own studies but I will say that sense we've done the hand holding study you know looking at these brain processes in response to distress and threat approximately, we've received an enormous number of emails from people who are in fact going through these terminal illness experiences. And while I can't say anything prescriptive about that, what we do hear descriptively is a lot of women, particularly, telling us about how their husbands were going through terminal illnesses or other kinds of ordeals, suddenly want to hold hands all the time. And they maybe didn't need to do that or want to do that before. So that suggests to us that people not only can use these kinds of simple, social contacts to reduce the suffering associated with these things but in fact they do all the time.

8. What type of laboratory environment is best for identifying a person’s core essential personality trait and studying connections between personality and behavior?

>>Oh yeah so people who have been interested in studying personality in the brain have for a long time, and you know people who have been interested in studying physiology in the brain, you know, or any kind of physiology and personality for a long time have sort of put people in this experimental situation where they sort of sit by themselves and they don't do anything. They're in what's called resting or resting condition and the idea is to sort of get them away from any situational influences that might keep you from identifying their core, essential personality, you know, that's revealed in their physiology. I think what we're finding is that it's hard to identify a person's core essential personality trait represented in their physiology. What you need is a situation that challenges a person's regulatory capability. So rather than putting people in a resting state where we try to eliminate any situational factors, we're moving towards being very specific about the experimental conditions under which we record individual differences that might predict future outcomes. So for example, we are, have studies where we're interested in predicting adjustment to college among college freshman. Turns out one of the big predictors of that is how socially integrated they become. So rather than get, you know looking at their prefrontal cortex activity, you know, and trying to use that to predict how well they adjust to college from a resting test where they're just sitting there doing nothing, we actually put them in a social challenge test. In this case we have them, we record EEG while they're in this count down, while they're waiting to sing karaoke in front of people. It's sort of socially stressed. They're gonna be evaluated. And it turns out brain activity during that task but not during resting predicts how well they become socially integrated later on because it's relevant to social stuff and it's also actually interacts with their level of social integration to predict their adjustment later on in college.

9. What does brain activity tell us about the creation of powerful emotions?

>>Great, so one of the questions we get asked a lot is you know how will knowing things about the brain have an impact on some of the practical applications that we're interested in? And I have a couple of answers to that. One is when people think of emotions behaviorally, they tend to think of one thing, like fear is a thing that you have somehow and that what we're dealing with when we're dealing with a phobic or a social phobic or a depressed person is fear or sadness. But in fact when you start looking into the brain, fear is not one thing. It's a multifaceted thing. There are many different components to it. And you find that certain kinds of interventions have affects on certain aspects of fear and other kinds of dimensions have other kinds of affects on different aspects of fear. And one of the things, by looking at the brain you can get a sense for what those different aspects are, how they're related functionally to different kinds of context and what you might want to do to intervene.

10. How can the measurement of brain activity be practically applied during diagnosis and therapy?

>>One of the things that we're interested in doing is using the brain as a kind of implicit measure of progress in therapy so one of the things that we've found is that, well lots of people have found, is that people are not very good reporters of their experience so they go through a round of therapy for some kind of, you know, problem that they're having and you say well did it work? And they say yes. This was the big criticism of the Consumer Reports study, you know, of psychotherapy that it was all just people's self report and that it wasn't really a good measure of progress. One of things we're interested in doing is seeing if we can use some fairly simple and inexpensive measures of brain activities and some EEG kinds of tools to sort of flag those individuals who may be saying that therapy worked but maybe aren't showing changes in the direction that we'd like in terms of emotional regulation capabilities like we talked about earlier and follow those people up and see if we can actually use that as a little bit of a prognostic indicator for who needs an extra round of therapy or who's likely to relapse.

11. What challenges or obstacles have you faced in your studies?

>> The biggest challenge for us in our studies is really getting at the mechanisms of the effects that we are seeing. So, what happens is with EEG kinds of studies that we do and with the MRI, certainly with the FMRI studies that we and other people do, the brain is the dependent variable. So, in other words, we are predicting changes in the brain, but were not ever really manipulating the brain to observe psychological changes later on. And that may seem like a subtle point, but in fact, it's a very important point when you want to really talk about the causal relationships between brain systems that we are studying, neural circuits that we are studying, and, you know, these behavioral or self-report kinds of measures that we are interested in a day to day sense. Now, animal researchers don't have to worry about this so much because they can lesion little parts of the brains. I mean in humans you can't obviously do that. There's some new measure method that are sort of exciting, you know, things like trans-magnetic cranial stimulation where you try to do proximal lesions with little magnetic signals, you know, things like that. But I think this is a major, major challenge for human research. If we really want to talk about causal relationship between brain and behavior, we are going to have to figure out a way, in humans, to manipulate brain and observe changes in behavior and that's a real, that's a huge challenge.

12. What direction do you see your research heading?

>> So, for the future we're really interested in moving beyond the brain as dependent variable and really using these processes. For example, how the degree to which holding the hand of someone else calms threat response regions of the brain, predict functional outcomes in people's lives that we all care about, how well are people--how good are people at taking care of themselves, how good are people at regulating their affect, you know, in a natural situation out in the real world, you know, how good are people at maintaining, establishing, and repairing relationships with others. All of these things that we know have huge impacts on people's health and well being. How does the brain and these brain circuits that we are interested in studying, how do they predict the future of those kinds of functional outcome measures in people is what we're really moving toward.

13. Are certain neurophysiological processes involved in depression, anxiety, and mania? How can neuroscience findings translate into practical interventions?

>> People are obviously very interested in how these different circuits that we're interested in studying, circuits and neurophysiologic processes, are related to, you know, psychopathology, conditions like depression and anxiety and things like that. And of course the answer is they are absolutely related to all of those things. I mean, in one sort of trivial sense they are related in that all behaviors is related to the brain. But beyond that, there's this increasing evidence that things like depression, anxiety, hypomania, mania, other kinds of things are related to a dysfunction of some of these appetitive approach related engagement kinds of circuits, dopaminergic circuits, serotonergic circuits, and other kinds of circuits that are related not only to affect regulation, things like the prefrontal cortex, but also to social engagement and social regulation. One of the things that is exciting is, the more we study the brain, the more we are realizing that things like social processes, emotion regulation processes, cognitive processes are all sort of intertwined in contributing their own sort of sources of variance to these conditions that we all worry about a lot. And so, we are definitely interested in pursuing how those relationships pan out"(Coan).

Positive Emotions: Michael Cohn

"1. How did you decide to pursue the career you are following?

>> Well, when I was an undergrad, I was studying chemistry and I was really interested in that because I like the idea of having principles and knowledge that could help you explain how the world works, help you make sense of things that go on around you. What I found though was when I was taking psychology courses and electives, I got too those things and I also got to tell other people about what I was doing without having their eyes glazed over. So, I decided that I really like being in a science which is also relevant to what's actually going on around me and that I can talk to other people about and relate to things in the real world.

2. What is your current area of research?

>> We do a lot of research with positive emotions based in Barb Fredrickson's broaden and build theory, which basically says that positive emotions evolved as a way of getting ourselves out of sort of behavioral ruts. When people are in good moods, they think of novel things, they try things they haven't tried before, they might talk to a new person or learn about something new, or go exploring somewhere they haven't been. And those are kind of a waste of time in terms of basic survival needs, but over time, those actually make you a much more skillful person, a more knowledgeable person, better connected, they also make you happier, they make life more fun. And people with those attributes are more likely to succeed in life, to survive, to reproduce, generally to do well. So, what we've doing in our lab is coming up with various ways to add positive emotions into people's lives and then see what does that do to them over time. Do they explore more, do they develop more personal resources for doing well at life, and then do they actually do better. So, the study I'm presenting, we use loving kindness meditation, which is a method for helping people learn to self generate feelings of love and compassion and kindness. And the reason that we picked that as an intervention is because it's something that people could do every day over the course of a long period of time, you know, usually in the lab if you want to make people feel good, you give them candy or show them a funny video, or, you know, show them pictures of kittens off the internet. And those things get old after a while, you couldn't have someone do that every day for two months without it maybe not working as well. So, we picked something that's a skill that people develop over time, and that is relevant to their every day lives, they can draw out in other situations, so rather than just feeling good while they're meditating, we were hoping, and what we found is that they also tend to experience more good feelings when they're interacting with others, when they're going about their lives in normal situations. So we assigned people randomly, either to take this course in loving kindness meditation, or to be on a white list group where they responded to all the questionnaires but didn't get the course until later. And we compared their outcomes on a bunch of different personal resources which is our term for a whole big class of things like a feeling that you're doing well in your life, a feeling that you can cope with the demands placed you, the ability to enjoy positive experiences, the ability to be present in the moment without being distracted by anxiety, the ability to bounce back from negative experiences, just all sorts of things that are relevant to whether you're going to be able to meet life's challenges and take advantage of life's opportunities. And what we found was that people who meditated were more likely to experience positive emotions, those positive emotions predicted developing resources, and those resources predicted people rating their lives as more satisfying, and also was reporting fewer symptoms of depression. So we were working just with ordinary people, these were working adults at a computer company in Detroit, and what we found is that adding positive emotions to their daily lives just made them happier with their lives, it made them function better in a very broad and general way and that positive emotions did that because it helped them develop skills for dealing with life.

3. What specific questions were you hoping to answer with your research? Why did you choose this particular population for your study?

>> Well, the company was a target of opportunity basically, we wanted to work with people who weren't just undergraduate students. In the past, we'd found that they were a little unmotivated, also they had so much other stuff going on in their lives, it was hard for them to really get anything out of just this one little intervention they do for a short period of time every day. So, we were looking for an opportunity to work with working adults. This was a company where the CEO was interested in meditation. Our teacher for the class was actually his personal life coach and meditation teacher, so he was very interested, and he agreed to let us come in and teach this course in the building, you know, while people were at work. And then we sent out an email to basically everyone who worked at the company and asked them are you interested in a course on meditation, and the people we selected were ones who were interested in it.

4. What are the short-term and long-term effects of positive emotions?

>> One of the things I really like about our lab and the work we do is that we look at both the short term effects, in terms of very precise mechanisms, what goes on at the moment you're feeling positive emotions. And also the longer term effects. So I'm going to describe the long term effects where people become more satisfied with their lives, become better at dealing with the challenges they face. The short term effects that we think lead to that are what we call broadening, which is the state where you're willing to look at ideas or experiences or relationships outside of, you know, the normal box you live in to try, try new things. And there's a lot of evidence from other research in our lab that does go on when people experience positive emotions. We've found that if you do something to put people in a good mood, and that's where we do use [inaudible] things like showing them standup comedy, or pictures of cute animals, or giving them little presents. They became more novel and creative when you ask them just what would you like to do right now, they are more willing to look at other people as being potential relationship partners, or of interesting people. We've done studies on implicit racism where people tend to not recognize the faces of people of other races as well, it's sort of they, a phenomenon they call, they all look the same to me. And we found that putting people in a good mood helps break that down. So, you have white students and they'll look at black students more as people with unique features, rather than as just representatives of being a black person. And along with that, they've actually become worse at, you know, drawing a strong dividing line between a white person and a black person, you show them more photos where a person is sort of white and sort of black and they have a much harder time saying, oh, that person is mostly black. Again, this isn't my research, this was stuff that my collaborators have done working in the same paradigm. And so what we find is that positive emotions sort of broaden you out, it's easier to make new friendships to understand new people to take other people's perspectives. And so the Holy Grail for us, of course, is going to be finding a study where we can add positive emotions to people's lives every day, see in the moment that's causing them to broaden their perspective, see what they do in that broadened state, and then show that that what's leads to the gains I talked about before, where they become better at dealing with life, more satisfied, less depressed. For methodological reasons, that's really hard for us to do right now, but it's something that we'd love to do in the future.

5. Did you find differences in results among men and women? Among people of various cultures?

>> The gender thing that's interesting in our study with the software company, the company itself was mostly now, which is pretty standard in computer industry, but when we're advertising for a meditation study, we disproportionately got females who were interested, so for once our gender population was actually pretty much exactly split between men and women. And we didn't find any differences actually. Men and women both responded pretty well and they both showed the relationship where experiencing positive emotions helps you build the resources. One of the reasons why I wanted to work with these folks was because again they weren't just the 18-year old college students we normally study. And if anything we found that these working adults who were in their 30's and 40's primarily actually responded better to this induction than we had more success with them than we've had with the college students in the past. And then we've also done a little bit of research with populations in other cultures. We got a little bit to replicate our work on the broadening effect among students in India and in Japan and we found very similar results. So, we can't say for certain yet that this is sort of a species-wide very general universal phenomenon, but we haven't been able to find people for whom that doesn't—

6. Please explain the development of positive emotions?

>>In our lab we usually treat all positive emotions as members of sort of the same general class and that's because what we think we're researching is a general motivational statement underlies all kinds of different emotions. In our meditation study, even though we were training people specifically in how to feel kindness and loving compassion, they also reported that as they went throughout their day they felt more amusement, more pride, more love towards other people, more relaxation, more interest in things and alertness. In fact every positive emotion we looked at they showed improvement on. And I definitely believe that there's important work to be done in terms of looking at different emotions and what their specific effects are. We know that there are important differences between how you'll act if you're feeling proud versus how you'll act if you're feeling relaxed or grateful or loving towards someone. That's not something we've investigated specifically because we're interested in looking at this very general phenomenon of broadening.

7. What types of interventions have been used, and what specific emotions have been seen as a result? >>

So this is the first one, the meditation is the first one we've used but it's been successful. Other attempts that people have made to induce daily positive emotions that have worked pretty well involve thinking about what they call your effected best self, which is when you actually talk to other people about the qualities that make you special and a good person and exciting and then they describe those to you and you try to work on those and develop them in your life. That's been found to pretty reliably increase people's positive emotions. Thinking about what you're grateful for at the end of each day has been shown to work although that one has a caveat that it actually works better if you do it a few times a week so that it doesn't get boring and predictable. That's the kind of work that I'm interested in seeing more figuring out exactly how to fine tune these things so they work consistently. Learning about your personal strengths in other ways has also proven to be helpful to people so there's a measure that's been developed by some other folks in positive psychology called the values and action measure where you learn about this whole array of strengths everything from creativity to critical thinking to determination to zest to humor and you find out which of those best describe you and then if you make an effort to incorporate those into your life you end up feeling happier over the long term. So it's still a developing field. There are very few things that work pretty well. I think what's interesting is I think they're not primarily things we think of as being sort of hedonistic, enjoyable, relaxing things so we haven't gotten good results with things like, you know, like eat some candy everyday or watch funny videos every day. Instead what we find is that helping people develop skills that make them better able to respond to life helps produce long-term gains. I think that's because those are the kinds of things that don't get old, that you can sort of keep developing into new forms over time.

8. What is known about the interventions that apparently do now work, such as eating candy every day?

>>We've actually never even tried that because there's already pretty good evidence that that kind of thing gets old. Also I think they'd probably see it as pretty manipulative. A lot of things like giving candy worked best if people aren't expecting, well it works best if people aren't expecting it, first of all, and it also works best if they're not expecting that your trying to manipulate their feelings whereas I think that would probably become clear over time.

9. How well do interventions work in longitudinal studies? Can certain activities break through a habitual mindset?

>> So I was talking about how a lot of the inductions we normally use that work really well in the lab when people aren't expecting them, showing them something funny, giving them a gift, those can get old over time. And that's based on a large body of literature, which is one of the most pessimistic things that's ever come out of psychology, suggesting that over time, no matter what you do, you're going to get used to it, and you're going to return to what they call your happiness setpoint, which is just this predetermined level of feeling good or feeling bad, that you're always going to be stuck at. So, they find that people who win the lottery, after a couple of years, aren't really happier than they were before. People who get married, you know, they show a spike in their happiness, and then it goes down over time. By the same token, people who become paralyzed in an accident, or who lose a tremendous amount of money, or who get divorced, they don't recover 100%, but they go most of the way back up to where they were before, after a while, that's just the normal state of your life. So that's what we're talking about is adaptation. And we're looking at aspects of an activity that can help you avoid that, that can break you out of that. One of the reasons we were so interested in meditation in the study we ran is because meditation involves mindful attention, which is a quality of really being aware of what's going on at the moment, rather than just sort of taking it on automatic pilot. And there's some evidence that that helps break people out of a state of adaptation, that if you're really paying attention to what you're doing in the moment, then you're going to capture some of that good feeling you got when it was new and fresh, you're less likely to just say, oh, yeah, the sports car, the beautiful weather, you know, that's all just same old, same old. One of the other things we're looking at is ways to produce positive emotions within challenging activities, ones that you have to work at a little bit, those aren't necessarily as much fun at first. People who studied our meditation intervention said that at first it was actually really hard and boring and they probably would have quit if it wasn't for science. But, over time, they got better at it, and then it became something that they could use to generate positive emotions whenever they wanted to. So I think making things a little challenging is also important, 'cause then it's harder for it to get boring.

10. Do you foresee a time when strategies to increase positive emotions will regularly appear in therapy settings? How might these help in treating depression?

>> Gosh, yeah. I mean, that's really important, giving people something to work towards, as opposed to just trying to remedy their immediate problems. And to be fair, that's something that's already done a lot in, in cognitive behavioral therapy, which is probably the most standard, manualized treatment for depression that we have right now. One of the things you do is encourage people to pay attention to the enjoyable things that happen to them in the course of a day, to learn to recognize them and savor them, and then to try and plan more of them. I think that inserting more things like that into therapy, maybe not just for depression, but for all kinds of disorders is going to be important because it's easier for people to take recovery seriously, to work at making their lives better if they have something to work towards. And so helping them build a life that's enjoyable and helping them recognize what they could do, and, you know, what it would be like if they were really using their strengths and their abilities is going to be really important.

11. Can emotions provide a pathway for such positive constructs as growth and meaning in life? What other areas are you interested in regarding positive emotions?

>> In connection with our current work, I think what's going to be most interesting is taking this meditation intervention, trying it with other populations, which we're already planning, so we're working on implementing this in university setting now working with a wider variety of ages and demographics and job descriptions, but also finding other ways to introduce positive emotions that don't just rely on this meditation intervention. We have pretty good evidence that it's the positive emotions and not anything else about the meditation that works, but it would be great to try this with other things and make sure that this is actually a general affective positive emotion. So we're interested in teaching people how to create a positive emotions portfolio, which is basically having a set of things that inspire you or uplift you or just make you feel better and that can be anything from personal momentos to silly photographs to inspirational saying, and having them to play that not every day but just when they're feeling particularly down or when they particularly need some help and see if that has some of the same effects remedying, you know, the really low positive emotion, negative events in your life rather than just trying to bring up the level of positive emotion every day. The stuff I'm really interested in, though, is actually the more short-term stuff we were talking about, looking at positive emotions in the lab and seeing how they do what they do on a really short, precise time scale. So one of the things that I want to find out is, what do positive emotions do to your attention when you're working on something? You know, [inaudible] sounds like it's all well and good when you're thinking about, you know, saying hello to the new person or learning about something exciting and new, but what if you're sitting and trying to like work on a math exam, is being in a good mood really going to help? And there's a lot of conflicting evidence on this. There is evidence showing that if you put people in a good mood, they actually do become kind of careless and inattentive. There's also evidence showing they can become more motivated and better at reasoning. And so I'm trying to get a clearer picture of what it is that causes those different effects and how you can, you know, get the beneficial ones and try to avoid the ones where you just become sort of careless and distractible, so I'm working on studies where you put people in a good mood, and then you have them working on a task, and we're trying to find out what the precise manipulations are that can allow them to, you know, open their minds up to all the possible approaches to a task, keep them paying attention to how they're progressing, keep them encouraged and optimistic without getting them to the point where they just don't care about it and wander off and do something else.

12. What direction do you see your research heading?

>> You know, I just think that positive emotions are useful as part of any kind of therapy for any sort of disorder, not just ones that deal specifically with feeling unhappy or experiencing low mood because they give people a sense of what they can work towards. You're not defined entirely as a set of problems or, you know, a set of pathologies. Instead, you can be defined as somebody who has a lot of strengths that can help you cope with your problems. So in the same sense that we use our positive emotion interventions to try and help people who aren't experiencing serious problems, you know, get a hold of better resources for dealing with their lives, I think it would be real useful to help people who are in really bad shape get a sense of what their strengths are, what's good about them, both as a way of seeing, you know, what kind of a life they can be working towards and in terms of seeing what skills they can harness to try and deal with their problems"(Cohn).