Colonizing Egypt: A Further Analysis on the Impact of Western Imperialism

- Colonizing Egypt: A Review on the Methods of Western Imperialism

The first of the Colonization of Egypt series introduces Timothy Mitchell and some of the overlying issues with Western Imperialism.

It is a remarkable feature of culture: the incessant need to define, categorize, and project order upon every natural or fabricated aspect of life. Possibly, these practices are adaptive strategies developed in order to better gauge, understand, and rationalize the incredible amount of information exposed to the human mind. “Enframing”, a term coined by Timothy Mitchell, may serve as the culmination of this process, wherein the Western world structures a representation of reality through the techniques of dividing, containing, and simulating.[1] The time of European expansion, commencing prior to the 19th century, witnessed the application of this method to various aspects of the social realm, where such practices as the idyllic re-construction of exotic cultures allowed appreciation for the otherworldly nature of foreign entities and apparent understanding of the same.

But, as time progressed, as did the intentions of the West, which now sought the organization of the entire world in respect to the innovative forces of modernity, capitalism, and globalization. Considering the history of colonization efforts in Egypt, it is of no surprise that the land of the pharaohs soon bore the brunt of European and American intentions. The “universal process” that ensued, determined on transforming the newly realized nation into a modern entity, is the focus of Mitchell’s Rule of Experts, the content of which reveals the struggle of the Western mind in categorizing the social, economic, and political processes of an alien institution. The consequences of these attempts, albeit addressed by Mitchell, are best portrayed by a pair of native writers, Sun Allah Ibrahim and Alifa Rifaat. Their novels, The Committee and Distant View of a Minaret, respectively, relay the experiences of a traditional people attempting to conform to an environment that falls victim to a series of attempts at re-structuring and re-categorization, originally intended for the ideal representation of the land of the pharaohs, which outside of the Western mind, proved non-existent.

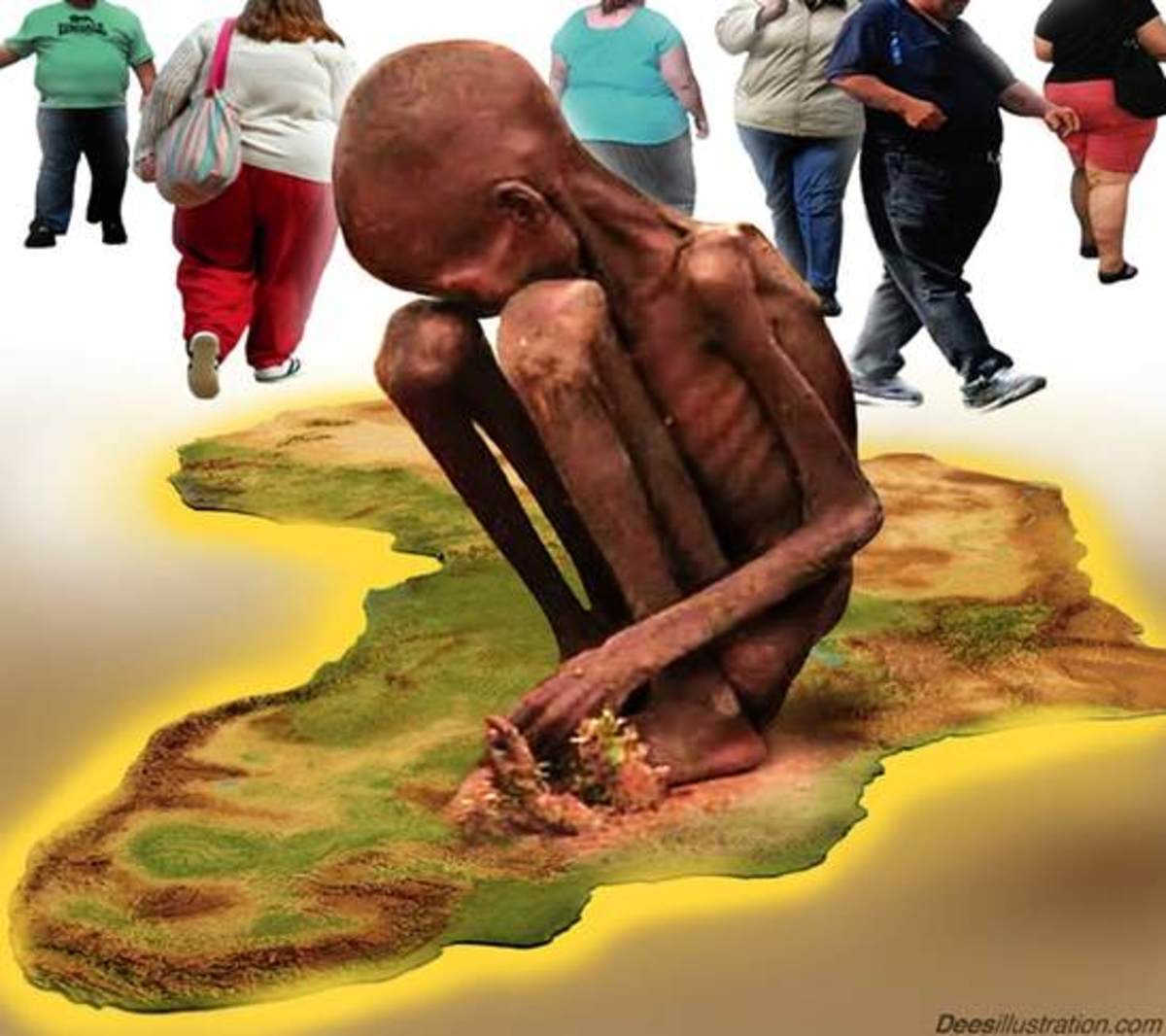

This re-configuring of Egyptian political, economic, and social structure was attempted -as European and American reformers argued- based upon an unseen logic, a “universal process”.[2] This idea involves the progression of modernization along an unseen, widespread pattern, driven by fateful forces such as technological advancements, capitalism, and democracy. Yet, Mitchell reveals, as he did in his previous work, Colonizing Egypt, that there is, in fact, a major rift between reality and Western representation.

This disillusionment is evidenced throughout Mitchell’s text, and instantly exemplifies the unsoundness of the enframing principle in the case of the Aswan Dam. This instance concerns the supposed importance of man’s influence over the natural powers of the environment, which, if extensive, reveals strength privy only to the modern state.[3] The construction of this massive waterway sought to assemble any and all human expertise, i.e. engineers, into one location from which the natural force of the raging Nile could be controlled. But, rather than separating the two realms of nature and technology, the man-made innovations led to natural disasters, such as deadly malaria outbreaks, which then influenced social factors, including the reform of public hygiene methods. The failure of this division was although overlooked, and hope was placed on the possibilities of appearances and organization, which, if successful, would successfully place human intention above as well as in control of nature.

Further examples of the idyllic reconstruction of Egypt include the re-arrangement of agricultural lands with the intention of improving industrial discipline and stimulating a mono-crop production for commercial uses. Promoted by Egyptian government, yet disdained by the rural peasantry, the actions suggested by Europe resembled the re-construction of a slave plantation, which was projected as the privatization of land, serving as yet another stepping stone towards modernity. The method that had proven itself lucrative for the West although failed in increasing the viable production of crops in Egypt, instead resulting in a definite rise of self-reliance as a form of resistance towards the global market.

With the successive failures of a variety of other re-structuring programs, including a more efficient method of documenting and accounting for Egypt’s populace, one of the final attempts within Mitchell’s work focuses on the economic and financial intervention by the United States, believed to have been one of the final stages in shedding the traditional rural world which having a state agricultural system implied.[4] Consequences to these actions were many: the goal of decentralizing the state and the promotion of “privatization” in the hopes of stimulating an economy suffered as most previous intentions had. Instead of eliminating exploitation, it was simply shifted from one loci of power to the next. Gaining a foreign source of finance caused only further inconveniences, with any national debt now owed to foreign lenders instead of natives. Additionally, the hopes of American based organizations, such as United States Agency for International Development, to develop a “private sector” again, inadvertently served to strengthen the state.

Still, while Egypt appeared seemingly stunted in its ability to modernize, capitalism and foreign ideals slowly infused itself with Egyptian culture and tradition. The diffusion of these global elements into a not-yet-globalized nation serves as the historical context of both Ibrahim’s and Rifaat’s novels. The former, whose protagonist is the embodiment of resistance towards the presence of the West, offers critiques on the elements of modernity being introduced, and at times adopted, by the Egyptian state and culture.

His critiques focus on the open-door policy and its outrageous commercialization practices, exemplified by the overwhelming presence and influence of products such as Coca-Cola. The Egyptian government and the inefficiency of its institutions are also attacked, of which the protagonist highlights such sectors as the medical system and its outrageous fees, the dilapidated housing conditions, and the poorly equipped transportation services. The committee itself, after which the novel is titled, stands as a representation of the powers to be, which the nameless hero challenges and eventually succumbs to.

Distant View of A Minaret although reveals an even more personal struggle against the changing tide of modernization, allowing a glimpse of its neglect of the Egyptian woman, who, even within the 20th century, continued to suffer the restraints of Islamic tradition while surrounded by a turmoil of cultural transformations. The collection of stories in Rifaat’s work feature a number of female characters that endure struggles indirectly impacted by the political and economic changes overwhelming the Egyptian city and countryside.

The fact that the author has had a limited exposure to the West permits a deeper understand of what remained of primary concern for women during the period of globalization. Her protagonists wish for meaningful relationships, the ability to provide for their families, and mostly, the hope of retaining their religious duties that seemingly become neglected by their husbands or other male relatives, who seek success in a capitalist realm. But, surprisingly, none of the women's tales hint at ignorance. They are fully aware of the historic watershed which they are witnessing, but refuse to let that cloud their sight of what is of true importance: their faith and self-awareness. Perhaps this is the reason why not even the re-structuring of the city, nor the additions of impersonal conglomerate headquarters and low-quality shopping marts can cause the women to lose sight of the distant spire of a minaret, which grants some sort of assurance, that Egypt will still remain Egypt.

Copyright Lilith Eden 2011. All Rights Reserved.

[1] Taken from the book review “Representing the Urban” but William Glover, from http://www.stanford.edu/group/SHR/5-1/text/glover.html as viewed December 10, 2010.

[2] A term used by Mitchell in the “Introduction” of Mitchell, Timothy. Rule of Experts.

England: University of California Press.2002. Print.

[3] Ibid. 2, at p. 21

[4] Ibid. 2, at p. 223