- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of Europe

End of Saxon England

Birthplace (not original building) of William

The Bastard

On 29 September, 1066, William, the Conqueror, more commonly called in his own time, the Bastard, Duke of Normandy, landed at Pevensey Bay, England, to launch a challenge for the throne of England. Determined to exchange his dukedom for a kingdom, William’s invasion was based upon on his belief that he was the rightful inheritor to the English throne following the death of the previous holder of the throne, Edward, known as the Confessor.

William was the illegitimate son of Robert I (1000-1035), Duke of Normandy from 1028 to 1035. His mother, Herleva, was the daughter of a tanner and William himself was born at Falaise in 1027; the actual date of his birth is unknown. William succeeded to the dukedom following the death of his father on a crusade in 1035. The young duke, William was only 12 years old when he ascended the throne, was faced with rebellion and, for more than a decade, his dukedom was in a state of what can only be described as anarchy. The final reckoning came in 1047 when, at Val-ès-dunes, Duke William defeated the malcontents and established himself firmly as master in his dukedom. William’s future career, in the territory now known as France, and beyond, was singularly successful.

Two years after Val-ès-dunes, William waged successful war against Martel, the Duke of Anjou (duke from 1040-1060) and, as his reputation grew, he was able to ward off attacks from those who thought that they might be able to take away from him those things that were already his. In 1054, and again in 1058, William was able to repulse invasions of Normandy by his nominal suzerain, King Henry of France. Both times the French king lost ignominiously and, following Normandy’s victory in 1058, Normandy was the premier military power in all the territories that today make up France. In 1063, William conquered Maine and, in the next year, he was able to re-impose Normandy’s overlordship over Brittany, which overlordship had been overthrown during the troubled times when The Bastard was trying to his authority.

Statue of William at Falaise

My Dukedom for a Kingdom!

In 1051, William made a visit to the English court during which visit Edward the Confessor seems to have made a promise to the Duke that, in the event the he, Edward, did not have any heirs of his body, William would inherit the kingship of England. This promise was made in furtherance of one which Edward had previously made when, as an exile from England, he had found refuge at the youthful William’s court at Rouen. Such a promise could not be expected to have been a welcome one to the English who were, at best, lukewarm to their king; indeed, most positively detested the Confessor. But, even assuming that the reaffirmed promise was made in earnest, there was no reason to think that Edward would not have any heirs of his own body. As it happened, 15 years after William’s visit to the English court, Edward did die without any personal heirs.

As we have seen, The Confessor, after he came to the throne, was an extremely unpopular monarch and amongst the English, at least amongst those who mattered, his death, without a heir was eagerly awaited. The closest person to a legal heir was actually Edward the Exile, the Atheling princeling and the Confessor’s nephew, a son of Edmund Ironside, a previous king of England. The Atheling had actually been brought over to England from Hungary by Edward, but the Atheling died and the situation was still as fluid as ever. In fact, at this time, the kingship of England was not strictly hereditary; following the death of a king, the Witanagemot, a body made up of the country’s leading figures, would meet and appoint a new king though, of course, blood relations to the previous king counted a great deal. More monk than king, Edward had practically no relations with his wife, Eadgytha, or Edith; in fact, for most of the marriage, the lady was under virtual house arrest anywhere as far away from the king as possible. At all events, following Edward’s death, William who, it seems, had taken the promise seriously, put forward his claim, a claim which was supported by the Pope and the Church.

Harold's Coat of Arms

The English Angle

From the English point of view, the death of a king whom they considered to be inept at best was all to the good. Following his death, they could replace him with one more to their own liking, and they had the candidate they wanted. Eadgytha’s brother, Harold, the Earl of East Anglia, a scion of, perhaps, the most powerful family in the land, was available; more importantly, he was willing. The fact that Harold’s family had played a strong role in securing the throne for the Confessor in 1042 when he returned to England after more than a quarter century exile in Normandy was also a major factor in the minds of Harold’s supporters. All that was required was the death of King Edward.

Unfortunately for English hopes, however, a problem came up. Harold, on a pleasure cruise sometime in 1064, was shipwrecked off the coast of Ponthieu; rescued, he and his entourage were handed over to the Duke of Ponthieu. The laws of Ponthieu, at this time, required shipwrecked folk to pay a ransom for the rescue that they had gotten. Between a rock and a hard place, knowing that William was suzerain over Ponthieu, Harold appealed to William to free him from the immediate problem, unpleasant imprisonment, which he faced. In making this appeal to William, Harold knew clearly the possible consequences; the promises made by the English king to the Norman duke were well known in England. However, the stakes were too high to allow himself remain a hostage in the hands of a minor player at a time when the death of Edward could come at any time. This view set out above is the Anglo-Saxon view; the Norman view, as set out in fairly early chronicles, is that Harold had actually come as an emissary from King Edward to reaffirm the promise that William would be the king’s heir.

William responded. Harold was removed from Ponthieu’s custody and moved to William’s court at Rouen, Normandy’s capital, where he resided for over a year. But, notwithstanding the royal treatment he received at Rouen, he was yet a prisoner. The news from England being good, that is, there was no immediate indication of the king’s death, Harold was content to remain at Rouen; indeed, when a minor uprising in Duke William’s dominions took place, he was eager to join the Duke to put down the uprising, against the views of his own advisers who thought that William might be trying to contrive his death. There was no such thought in the Duke’s mind; Harold’s fame as a warrior in England was similar to William’s fame on the Continent. William’s interest was simple and straightforward; he wanted to assess at first hand the abilities of a potential foe.

The news that Edward was close to death brought matters to a determination. Faced with the collapse of all his life’s ambitions, Harold swore an oath to uphold William’s claim to the English throne; additionally, the Earl agreed to marry the Duke’s daughter, Adela, as soon as the young princess came of marriageable age. For William, though he must have known that an oath exacted under such circumstances could never bind Harold, it met his needs. For Harold, it was a bit more difficult.

Harold’s claim to the throne was based purely on the fact that he was the preferred candidate of the English party. There was a determination in England to put an end to what seen as Norman domination; the Confessor, on his return from exile, having placed several Normans in positions of power so there was the need for prudence in the pursuance of Harold’s claims. The death of the Atheling was a welcome development to the English party; Harold’s unfortunate fall into William’s hands was not, but people must play the cards as they are dealt!

Harold returned to England.

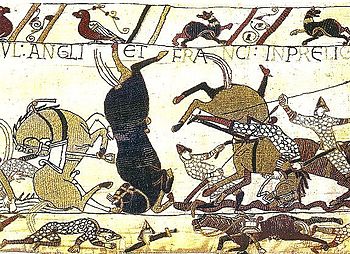

Depiction of Battle of Hastings: Bayeux Tapestry

If the Duke did not fear our swords, he would not seek to blunt them by a Papal anathema!

The Confessor finally gave up the ghost on 5 January 1066 after falling into a coma towards the end of the previous year without making any clarifications as regards his wishes for the inheritance. The king had briefly regained consciousness, it is said from the Anglo-Saxon side, and commended his wife and committed the kingdom to Harold’s care. The Witanagemot met on 6 January and chose Harold as successor; he was crowned King of England on the same day by Archbishop Stigand (died 1072) who, himself, was under a papal ban at the time. In a letter that he wrote to William, King Harold explained that the English crown was not his to dispose of as he wished; it belonged to the English people and the people had expressed their wish to have a home-born person as king. Further, breaking off the engagement with the Norman princess, Harold explained that his subjects had earnestly entreated him to marry an English lady and he had given in to their entreaties.

Whatever William might have felt as to the likelihood of Harold actually living up to the terms of the oath which he had sworn, he was somewhat disappointed for he had a great personal liking for Harold as, indeed, Harold had for the Duke. At all events, William saw his way clear and, once he had secured the support of the Church, he set out for England in search of a king’s crown.

The news of the Norman landing reached Harold in Yorkshire where he and his troops were celebrating a victory at Stanford Bridge over another one of England’s would-be king, the Norwegian king, Harold Hadrada, who was supported by Earl Tostig, Harold’s brother. Marching south with phenomenal speed, Harold arrived at the battlefield on the night of 13 October. William, who in the meantime had moved his main camp from Pevensey to Hastings, immediately sent an emissary to Harold. Reminding him of the promises that he had made on oath, William went on to say that if Harold would honor those promises, then he, Harold, would be second only to him in all of England. The offer was rejected and William promptly advanced to offer battle arriving at Senlac hill at about 8 a.m., 14 October, from which point he observed the English taking up their position along a ridge about 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) away. The extent of the position was about 800 yards (about 731.5 meters) and the strength of the army was somewhat between seven and eight thousands, although late coming stragglers continued to arrive throughout the day.

The battle itself may be divided into 4 phases, to wit:

- The Norman bowmen advanced within bowshot of the English and opened fire. The English, having no bowmen, could do nothing but huddle behind their shields, which had been massed to form a wall, and wait out the attack.

- Following the withdrawal of the Norman archers, the Norman infantry attacked the English position, but no impression was made on the shield wall of the defenders. In fact, the left wing of the attacking force, composed mostly of Bretons, broke and the English right, contrary to Harold’s strict instructions, broke from their position and gave chase down the hill. The flight began to extend to the center of the invading force, made up mostly of Normans, where the Duke himself was fighting, when a rumor spread that the Duke had been killed! William had to remove his helm and show himself in front of his troops in order to put an end to the rising panic. A pause in the fighting ensued, and the pursuing English gradually returned to their lines.

- William now launched his cavalry, much earlier than he had intended, in a general assault, but the horsemen fared no better than the footmen had done earlier: the English shield-wall was able to resist and the cavalry was forced to retreat. They were pursued by the English, but the English fared no better in this pursuit than they had in their earlier pursuit of the infantry.

- Then William showed why he was the most famed and successful warrior in Western Europe. The assaults by the separate sections of his army having failed to achieve his aim, he decided to use the separate arms in combination. Applying the principle of cooperation, he combined the assaults of the various arms of his force. As the archers shot at the rear end of the English fortification, the cavalry assaulted. The tactic was a success; the English stand was broken, King Harold was killed, as were his brothers, Gyrth and Leofwine. It was a complete Norman victory. Just another half hour would probably have brought about an English victory; just 30 minutes!

Harold’s dead body was brought to the Duke who refused an offer by Harold’s mother of the body’s weight in gold for the return of the body. The body was handed over to William Malet, one of the Duke’s followers, who was partly Saxon himself, for burial and the body was interred, probably at Bosham church in Chichester just in sight of the English Channel on that coast that he had defended so bravely, but not, just not enough.