Toward a Food-Secure Future for Everybody: Learning To Grow Skirret, Perennial Vegetable #1 on My List

Skirret: the basics

Skirret is a root vegetable that looks like a skinny, crooked pale carrot, or better yet, an alien parsnip. Whereas we thin carrots and parsnips and grow them individually, one root at a time, skirret is grown in clumps. To harvest it, a clump is dug up and the roots, bunched together at the top, are separated.

Skirret's a historic vegetable. It was very popular in Europe during the Tudor period (roughly the 1500s) until it was replaced by crops more familiar to modern grocery shoppers: potatoes, carrots, parsnips, and celery. Parsnip and celery are two of skirret's relatives, with a comparable flavor. In some cultures, especially Asia, this vegetable was cultivated for its sugar content. Rather than eat skirret as a side dish at the table, people used the thin white roots in the same manner as the sugar beet.

My interest in skirret is that it's a perennial food, with the bonus of being a root vegetable. I am interested in stable food sources easily produced at home. As a root crop, skirret is something I can depend on. Changes in weather are not as likely to kill the whole thing off, in the way that a hailstorm or a brutal heat wave could destroy a tomato or squash plant. And skirret can be propagated twice a year, once in the spring by breaking off young shoots and once by dividing the root clumps in the fall. I'm a very practical person and skirret is a very practical crop. Plus I'm fond of parsnips, and I've had good luck growing parsnips in five-gallon pails, which I also use for skirret.

Some perennial plants are invasive; Jerusalem artichokes and comfrey are examples This is often why I put plants into buckets where they can't get into trouble. But skirret is not in time-out for going outside its boundaries. It grows in clumps, rather than spreading out.

Alternate names and spellings - a bit of history

The most common spelling for this plant is "skirret" but I have also seen "skirrit." When dealing with historical records in various languages recorded hundreds of years apart, it's not easy to decide the best way to modernize a word taken from texts dating back to the Medieval period, or even back to Roman times.

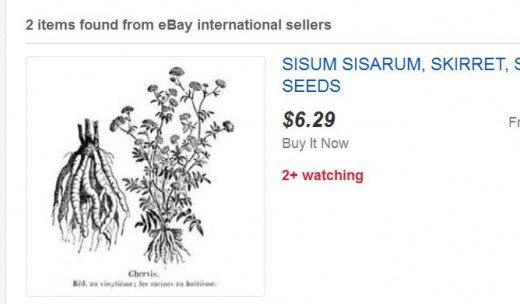

In English, there are a couple of other names used for the same plant, one being "chervis" and another being "crummock." I've seen "chervis" used by growers in Eastern Europe, while "crummock" is a Scottish word.

All over the world, on several continents, people who grow and cook with skirret use a variety of other names for this old favorite. These names include girole or gyrole, escaravia, and suikerwortel. This last is Dutch for "sugar root," and there are a lot of other names for skirret which all translate to sugar root.

It might be helpful to have an accurate historical record on where skirret was first cultivated and how it spread throughout the world, but those details have been lost to history. The origin of skirret is muddled at best, with writers cliaming that, for example, "these thumb-shaped tubers originated in China." I had my doubts about that origin story immediately as skirret roots might resemble a finger (say the long crooked finger of a strange humanoid creature) but not a thumb. I've also seen reports that skirret was brought by imperial decree from Germany to ancient Rome. And more than one historian's account of the skirret story shows a weak sense of geography and culture. English writers from the 19th century are fond of opining that the plant with the narrow white roots came from Greece, or maybe Russia, or perahps it was northern Iraq, as if those places had anything in common except for being far from the writer's home.

So we've got a bit of circle going around, really. If we knew where skirret came from, we might be able to trace its name more clearly. If we knew more about where skirret got its name, we'd have a small light we could shine into the murkier parts of botanical history.

Just to make it all a bit more confusing, the French have several names for skirret. One of these is "girole," but if you Google that, you often get references to recipes using the girolle, which is a type of mushroom. Even worse is "chervis," since it's so close to "chervil," and chervil is in the same plant family as skirret. There's a rooted or tuberous variety of chervil which is close to Hamburg or rooted parsley which is close to parsnip which is close to skirret. The mind reels.

While I am negotiating the purchase of skirret roots, plants, or seeds, it would be so easy to end up with the wrong thing. Since I have mostly worked with Europeans who speak English as a second language, and my substandard French is only slightly better than my terrible Spanish, the possibility of language confusion is large. In the case of seeds I order through the mail, it might be weeks before I even realize there was an error which grew out of two words like "chervis" and "chervil" which are one letter apart. I would have to plant them and then have them grow big enough to say "Hey, wait a minute. . .." And that's if I can tell the difference!

It's all confusing, and since I personally know nobody who grows skirret, I have to be sure that what I plant is actually skirret. As I try different seeds from various sources, I expect that they'll be different from each other. There might be a variety better than the plant I first ordered from the perennial plant nursery. Since I have so little experience and have only seen this one plant, then if new seedling starts look a bit different, I want to be as sure as I can that the plant I'm lovingly tending is an actual skirret start.

I am trying seeds from sellers I don't know, so I have to be sure I didn't just get weeds or something. Maybe a hoaxer might deceive me, or an experienced grower doesn't know what they have. Even with knowledge and good intent on the seller's part, a stray seed from something else could creep in with the real seeds. And, you know, I saw that movie "Into The Wild" where the young man think he recognizes an edible wild plant, but instead he eats a plant which looks very similar. It turns out to a toxin which builds up in his organs and kills him. Whoops, sorry, should have issued a spoiler alert.

Okay, that's dramatic. I don't think I will accidentally grow poisonous roots that will kill me. But it's an important issue for me is to make sure that what I'm planting is definitely skirret.

This is where I've found comfort in using skirret's Latin name whenever I can.

To look it up, I need to know how to spell it

Skirret's Latin name and why I care about that

Though I share writer Susan Griffin's doubts, expressed in her 1978 book Women and Nature, that the botanical naming system isn't really the best way to characterize the plants in our world, the current system is what we have. I don't think anyone is interested in any new plant-naming system I might invent.

Botanists mostly give plants a two-word name following the pattern Genus species, with the second word italicized. The Sium family, to which skirret belongs, has plants which are similar to parsnips, with some of these plants growing in the ground and some of them in or near the water. (The wild version of skirret is called water parsnip.) This group is a subset under the classification of the "family" in this plant naming system. Sium plants all belong to the plant family known as Apiaceae, which refers to the way their pleasant odor attracts bees. The other name for the same plant family is Umbelliferae, and you probably instantly saw the connection to ":umbrella ".there. When these plants are at the end of their growing cycle, they put out spoked wheels of seed stalks which do look a bit like parasols. Other plants related to skirret also put up these little "umbrellas": carrots, celery, dill, celery root aka celeriac, curly and flat parsley, rooted or Hamburg parsley, chervil, and fennel.

So we've got the family, either the bee family or the umbrellla family, and then the genus Sium, and then the species name sisarum, which makes skirret's Latin name Sium sisarum. For some reason, when I was learning that, the fact that both words start with "Si" stuck in my head. I kept hearing a 1955 song that went "Ay Si Si, we want to mambo," by the Dootones. I suppose some song with "sis-boom-bah" might have worked too.

This bi-nomial naming system is universal, which is handy in this case. Though the plant start I began with came from a U.S. grower, some sellers I've bought seeds from were located in Europe. We all know that the same words -- "football" being an obvious example -- don't represent the same thing everywhere. I want to make sure that any seeds or plants I get are really skirret.

Besides using the right term when buying the seed, I also need the right word to do research. Since skirret has almost drifted into history, it's not easy to find out how to grow it and take care of it in various climates. I want to see what others are doing with their growing experiments, and to make sure we're all talking about the exact same tuberous plant, it's helpful to have the Latin name

Argh, even Latin doesn't always work if "Sium" becomes "Sisum"

Seed packet labeled with correct Latin name

Why do I grow skirret in containers?

I grow at least half of our garden plants in containers anyway. We live in a small Maine cottage on a small lot, with lots of shady spots. We have to grow things in any spot we can find. Containers are easy to tuck into awkward little spaces. Also, since we have a nice shady lot which makes the house not so hot, I can move portable plants in their five-gallon white plastic icing pails. Some spaces are sunnier at a different time of the day, at a different time of the growing season. For example, I move them out of the shade when trees get all their leaves and overhead branches fill in.

The buckets are a permaculture thing too. One of the basic ideas is to use resources like space, water, soil, and fertilizers wisely. Buckets keep everything good close to the growing plant. I use less of everything and it all goes to make happy, healthy vegetables and leafy greens.

Another advantage to the containers is that they mostly only hold what I put in them -- the seeds or the seedling and the soil and the water. Maple helicopters do fly in now and then, but other than that, weeds don't creep in as they can't extend vines into the growing space. Slugs and nematodes can't slither in from the garden soil.

And one more reason? I'd had good success with parsnips -- a close relative to skirret -- grown in deep pails. The soil didn't seem to get impacted so the parsnip roots grew deeply and not so crooked or split. And when it was time to harvest the parsnips, all I had to do was tip the bucket onto a tarp.

Skirret grows well in a container like this 5-gallon bucket

Getting started with my first skirret plant

I bought a skirret plant start online from a nursery a couple of states away. The nursery specializes in perennial plants, and the price was reasonable so I ordered one plant and paid for priority mail shipping.

The plant arrived in good shape. It was about eight or ten inches tall and had a couple of slim branches with a few leaves on each. I wanted to get it into dirt as soon as possible. I didn't think about how deep a pot I should use. I just grabbed a square planter that held a few cubic feet of soil. I knew skirret was a root-based plant, but maybe in the back of my mind I calculated that I would not harvest any edible skirret roots the first year. All I cared about, in that crazy busy time known as Spring, was getting the plant well-settled and happy so it would grow large enough to be divided a few months later.

Over the spring and summer, the skirret plant grew to be between two and three feet tall, with a couple branches each. The square pot sat in my driveway. We are a one-car family with a really long driveway to a garage we don't use. So I have converted about two-thirds of the driveway into a container garden. I built a couple of large raised beds and then I put out a lot of buckets and pails and windowboxes, filled them with potting soil, and put plants in them. We don't have much growing space in our yards, so I work with what I have.

The area is fairly sunny, but I do live on a shady plot in a neighborhood full of houses which are close together and surrounded by large old trees. So the young skirret plant got perhaps four hours of full sun a day and then another two or three hours of dappled sunlight or alternate sun and shade. I made sure the planting bucket had enough drainage: three or four holes, each the size of the nail on my little finger. I watered the plant a couple of days a week when it didn't rain enough.

Baby skirret plant

Like many permaculture plants, skirret is easy to tend

I don't do much to keep the skirret going. I keep it watered so the roots will be crisp. Dry conditions, I've heard, make it woody and fibrous. And a tough texture may mean a bitter than sweet.

Skirret doesn't react to hot or cold temperatures, it is fine in most soils and it doesn't get blight or other weird plant diseases.

Gathering seed from my skirret plant the first year

Like the other members of its plant family, skirret sends out umbrella spokes of stems with seeds at the end. When I saw the seeds developing, I wasn't sure when to gather them, or quite how. I settled on holding a shallow container under the seedheads and then gently shaking or brushing the plant to see which seeds would fall off easily. That's what would happen in nature. This did seem to shake loose the seeds that looked more "ready" to me -- darker in color and harder in texture.

Saving skirret seed

Then the seeds didn't seem to ripen any more

And for a while, that worked. But then the weather changed, and I was worried I would lose all the seeds on the surface of the driveway during a single windy night. I decided I was better off to gather them and take the chance that they might ripen some if I left them on the stems.

Also, I wasn't sure if the young plant had developed seed the right way this first year. Skirret is supposed to flower in summer but if that first plant made any blossoms, I missed them while I was away for a short trip to visit family in June. I didn't know if a plant's capability to reach full flowering stage might mean it makes better and more copious seed, but I suspected so. But these were the seeds I had, so I put them all together in a junk mail envelope and labeled that Skirret 2014.

Cow parsley flowers look like flowering skirret

Divide and conquer -- the first winter

The original skirret plant got about two or three feet tall and then it stopped growing and sent out seed stalks. As described above, I gathered the seeds. When I was sure the skiret was no longer making more leaves or lengtheneing its stems, I judged it dormant enough to dig up and look at the roots.

There was a small clump of white roots, each about the diameter and length of my ring finger. I divided this root clump into three parts, like Ceasar's famous description of Gaul. I replanted the basic center stem in the planter i'd used to start my first plant, and then put two side pieces into five-gallon white plastic icing buckets with drainage holes drilled into them.

Skirret is a perennial but I live in Zone 4, with heavy snows and harsh cold winters. I just didn't dare leave the young plant outside to endure January and February in Maine. I let the skirret plants stay outdoors until November, then I brought all three containers up the attic stairs and put them near the sunniest spots where winter light would come in through the windows under the eaves. It does get cold up there in the coldest part of winter, maybe a temperature in the high 30s, but skirret is famous for being cold-tolerant. If it was going to work for me as a reliable food crop, I had to push it through the equivalent of a mild winter and stay alive till spring.

Down from the attic & needing to be "earthed up"

Propagating by seed

I have at least three reasons for wanting to grow skirret by planting its seeds:

First, while root division does work, how I get more plants is to take a small- to medium-size clump and divide it into three small clumps once a year. If I had harvested the skirret I got the first year, I would have had enough roots to cook up and eat one small portion. I need to produce enough skirret that I can eat some every now and then, divide the rest in the fall for replanting, and keep the crop going by seeding new plants in the spring.

Second, I want to see if any of the seeds I get from different growers provide new varieites of skirret. I have heard that propagating from seed might mean getting genetic "throwbacks" or wide variations in the plants I get. Would the new varieties be better or worse than the one I already have? Maybe some other type would grow faster or make more roots, or better-tasting roots. Also, when there's only one kind of plant, opens up vulnerability. If a disease or an insect took out the type of skirret I'm growing now, I would have no fallback. I like the idea of having variations to see how adverse conditions affect them. If I don't want the varieties to cross, I can grow each kind on the opposite sides of the house to limit cross-pollination.

Third, I want to make skirret and other perennial foods more available to other gardeners and people interested in a more food-secure world. While I might be able to share a root clump with a friend in the next couple of years, I really need most of the roots to start more skirret plants here at home. But each plant makes at least a couple dozen seeds, and I think it's more realisitc to share those with others. And seeds are much easier to mail than a live plant.

Trying out a new variety

Sources for seed

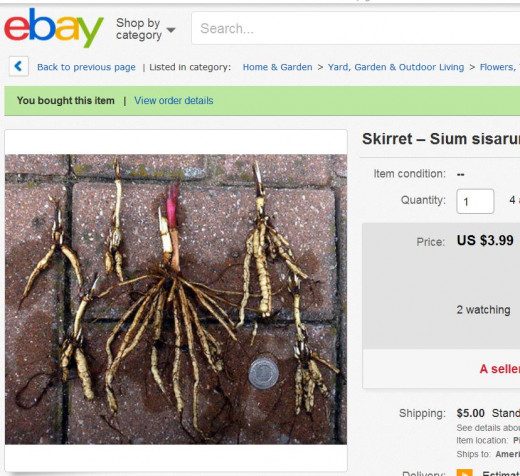

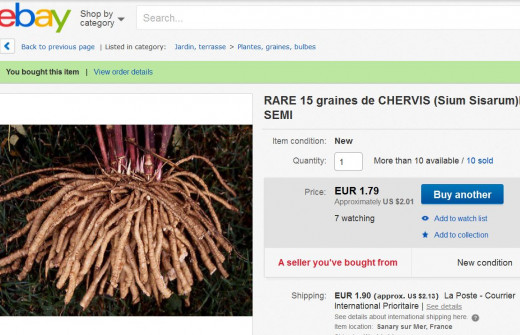

So far, most of the people I've found who will sell me skirret seeds are gardeners who live in Eastern Europe. Thanks to eBay and PayPal and magic online conversions of dollars to Euros and back again, I can buy from people in Poland and other places.

It's not very easy to find skirret starter plants, and they're pricey. I just can't afford to buy several starts, plus there isn't much demand for them so they are scarce. It doesn't seem fair to me to grab them all up for myself. I'm all about spreading the word and getting plants to other people. So I search the internet to find sellers who have some Sium sisarum seeds they'd like me to buy, and I mostly find those people on eBay.

Here's another seller from whom I bought skirret aka chervis seeds

seed soaking

How's the seed germination going, you ask?

Not that well.

i've tried various strategies, which is what I've done in the past with other perennial plants like Good King Henry and Malabar spinach. When trying new crops in the past, I've planted seeds in a few planters, had them fail, and planted some of the same seeds in different containers or used different places, or different seeds. Eventually I got the plants going.

The only real advice I could find on starting skirret was a tip from a British gardener, Vicik Cooke, who tends a royal kitchen garden at a castle. She suggests letting the soil warm up before seeding it with skirret.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/gardening/howtogrow/fruitandvegetables/11421128/Skirret-the-forgotten-Tudor-vegetable.html

One strategy I experiment with involved the skirret seeds I saved from last summer. I tried scattering the seeds on the surface of the soil around the main stem of the skirret plants I had started in buckets.

I've had various hassles since planting those, including several days of torrential spring rains that may have washed the seeds down the sides of the containers on the inside, between the soil and the inner surfaces of the buckets. Or did the seed float on a couple of inches of water and then resettle on the soil, evenly or unevenly? Did it matter if the seed was no longer covered by the potting soil? The seeds were so small and dark and I could not tell by looking.

We also had a humongous fall of silver maple seeds this spring. Normally, we get quite a few, but this year, I swear we got double the usually seedfall. Of course, the helicopters or whirlygigs fell into all my planting containers including the skirret. I picked out some of the winged seeds, but sometimes they were hard to remove and I didn't want to take the skirret seeds out with them. So I have examined any possible sprouts and found, of course, mostly baby maple trees. But I have seen a start in one pot which could possibly be a new skirret plant.

The last hassle was my own doing. When I added skirret seeds to the soil around the potted skirrets I had from last year, I didn't think about adding more soil first. You know, it was spring and I was crazy busy. Then I seeded the soil around the skirret stem and it put me in the spot of having the established plants growing in less soil than they needed. I couldn't add more soil because I would bury the new seeds. Well, it's always something, as Roseanne Rosannadanna used to say.

Possible skirret start?

Propagation by root cuttings & by replanted shoots

The seed-germination strategy is still being developed, which is a vague way of saying I'm having some trouble getting the seeds to sprout. I have another reason to want an alternative method besides sowing seeds. Some people say skirret plants grown from seed are not as strong as root-divided plants.

While I'm waiting for the seeds to germinate (if they ever do) I want more ways to increase my skirret yield. One of my new strategies is for spring and the other is for fall

This year, before I take the skirret buckets up to the attic to overwinter, I will add more soil around the main stems of the plants. My goal is to encurage new baby shoots to emerge next spring. I have read about propagating skirret by gently breaking off these new buds as they poke up when the weather starts to warm, and replanting them away from the mother plant.

I've also read about a British gardener who has had success by cutting up a single skirret root and planting the pieces. This is commonly done with plants like comfrey. I've done it myself and gotten new plants easily. So I will take the skirret root cuttings in the fall when I am ready to un-pot the skirret and divide up the root clumps.

Propagation by cutting up roots

recipes modern

What does skirret taste like?

Food writer Sandra Nex in "Gardens: Eat Like A Tudor," her March 29, 2013 article in The Guardian, describes skirret as tasting like parsley. Snadra Lawrence, a writer for The Telegraph, another UK newspaper , describes skirret's flavor as dainty and delicate. A description I found from an 1837 cookbook says the white skinny root's taste is between parsnip and celery, but "more palatable" than parsnip.

I can't tell you from personal experience. My plants aren't established enough for me to have harvested any. But the skirret is close in the plant family to the parsnip. The few eople who cook with skirret sometimes describe removing the woody, potentially bitter core of the largest roots as one would with big parsnip roots. So I would guess that when baked, the slightly bitter tang of raw skirret root might become a mild sweetness with a touch of bite which makes parsnips one of my favorite root vegetables. A food historian has used the phrase "peppery aftertaste" to express the same thing I mean by "tang." Further evidence for my theory comes from all the versions of "sugar root" which serve as alternate names for skirret: "suikerwortel" and so on

Modern and historic recipes for skirret dishes

When I was young, and visiting my mother's family in their Appalachian home, I saw people using a spring onion, both green top and white globe, as a relish on the plate, the way someone might add a little side dish of salsa or chutney to give their food a bit of zing. Old cookbooks sometimes suggest using raw skirret this way. "Pilgrim Seasonings," the Smithsnian affiliate site celebrating Plimoth Planation (which I grew up spelling Plymouth Plantation), about washed, cut-up skirret root from an old source: "maybe having some by the side of your plate to eat a spoonful of beans and then a crunch of carrot)…..but if you have skirrets, they really are better off cooked before eating."

In the 1500s, when skirret was at the height of its culinary popularity, there were two basic kinds of recipes available. One option was very fancy, often involving a "pie" (or "pye") that was closer to what I would call a sasserole, or maybe even a cobbler. This dish was a mix of sweet and savory. Honestly, the "recipes" mostly seemed to mean making a fancy crust or pie shell but then just filling it with whatever foods came to hand, finishing it by tossing in some skirret. The white roots are very mild, apparently, and take on other flavors easily so it would be hard to ruin a "pye" by tossing some skirret into it.

More frequently, the suggestion in old recipes is to boil the skirret, the way old-timers seem to have boiled everything. Sometimes the skirrets are cooked alone, and sometimes they're stewed with carrots or turnips. Some authors suggest adding a splash of wine or a spice or two, but basically the technique always involves a cooking pot, fire, and bubbling water rolling on the surface. A slim, mild root like skirret really wouldn't stand up to that for long, but then I suspect our ancestors ate most vegetables mushy and pale. (Not that different, actually, from the food I grew up eating at home. But that's a subject for another day.)

The best pieces of advice I have seen for using skirret in modern cooking are to use a cast iron skillet and to use the cut-up skirret root as you would scallions or young spring onions. The skillet idea makes sense to me as cast iron is what a grandmotherly woman once taught me to use when I prepare parsnips, skirret's close cousin. I gently parboil parsnip roots, cut into "coins," right in the skillet, and then add a little olive oil as the water evaporates. The parsnips get a lovely crust on the bottom which combines well with the mild sweetness of the soft sweet root.

And the scallion idea also makes sense as even an enthusiastic gardener is not going to be able to produce truckloads of skirret roots the way one might grow beets or turnips. Skirret clumps are not large, and they take a little work to harvest. This is more of an accent food; skirrets can be added to a dish to make a vegetable medley more interesting.

To core or not to core? One complaint in old manuals is the plant’s “woody core” but so far this has not been an issue for the historical growers and chefs who work in the royal gardens at Hampton Court in the UK. “It could be because it’s just a year old,” says Vicki Cooke (mentioned earlier in this Hub), “but we have found that you don’t even need to peel them – just give them a good scrub and they’re delicious. I like to eat them raw straight out of the garden.” She'd fit right in at Plymouth Plantation.

Re-potting and soil depth - it wouldn't be me gardening if I didn't make mistakes

Part of my gardening style is to goof and then fix the goofs. I share my mistakes in the hope that you, kind readers, won't make the same errors.

First goof: I should have "earthed up" arund the skirret starts that were growing from the root division plants. I didn't think about how the dirt needed to be deeper. This became a problem when I wanted to try adding some seeds from the first plant I'd grown the summer before. Once I added seeds to the soil around the plant, I realized I couldn't add more soil now or I would be burying any new skirret starts. Now the established plants would be in soil that was too shallow for a root-based plant. I still didn't plan to eat any of the skirret roots, but I wanted plenty of room for the root clumps to spread so I would have more to divide the following autumn. All I could do was wait for a while to see if the seeds germinated, and if they did, to let the shoots grow high enough that I could add more potting soil without burying the tops of the shoots

The other goof is that I replanted one of the divided plants from the first year into the original container. The square planter was okay but not nearly deep enough for good root development. I think that day in early spring, I was tired and it was easier to prep two replnating buckets than to prep three. So then at the start of the summer, i realized what I had done, and then I had to find that third bucket and move the skirret to a more adequate bucket. I have posted photos here of fixing that particular goof.

Moving skirret from a planter too shallow for a root crop

Health benefits of skirret?

Nicholas Culpeper, a famed herbalist who wrote in the 1650s, said skirret root was "of a pleasant flavor" and "wholesome," and that eating it was good for you. He described the medicinal value as not only diuretic (helping the body produce urine) but cleansing to the inner bladder wall and healing for a jaundiced liver.

Harvesting and storage

Skirret is very cold hardy. It grows in the colder parts of Europe, including Scotland.

Like carrots, parsnips, turnips, beets and other winter vegetables, once the foliage dies back, the roots can be left in the ground for a while as a storage method. In fact, frost sweetens root veggies. The trick is to get the food out of the ground before the ground freezes solid and you'd have to chip the roots out.

http://lichen.csd.sc.edu/vegetable/vegetable.php?vegName=Skirrit

Once it's dug, skirret can be stored in the fridge or in a cold cellar. I've seen the advice not to wash the roots before storing them and to wrap the skirret. The advisors didn't say what to wrap it in. I'm thinking I will try both plastic and newspaper. If there are enough of the roots, I may try putting a couple into damp sand, which is how I've stored carrots and parsnips in the past.

High wind advisory, or there goes my sturdy stem

Here in coastal Maine, you never know when gusty winds might blast your garden. Up till June, my skirret plants had been fine, and then the tallest plant took a hit when the rough winds went up into 30 or 35 mph. I came out one morning to find the tallet skirret stalk, which was in a bucket on a downhill slope, had been pushed over by the same whipping blasts which had done things like torn large cabbage leaves and knocked over a flower windowbox.

I went into my garage and found one of those 3-sized heavy wire frames which hold up yard sale signs, the kind with spiky wire ends you jam into the ground. I criss-crossed the wire and made the top into a big loop. I jammed the two ends, the parts that usually go into the lawn, down into the pot, hopefully away from the rooty part.

I leaned the skirret shoots, which were bowed but not broken, against the wire loop, without tying it or anything. I leaned the whole thing against the back of the house and hoped for the best.

A few weeks later, the plant is flourishing. It hadn't occurred to me that the shoots might like support, something like a tomato frame. At this point I don't want to mess with the skirret plants as they are, so I will wait till next spring to add supports around all the new skirret plants to see if this makes them branch out and grow more freely.

Homeade wire support made from an upcycled Yard Sale sign frame

A week or so after being blown over by harsh winds

Skirret is just one of many self-renewing foods

There are lots of growable edibles which don't have to start as germinated seed every spring. Some of the foods are true perennials, while others are biannuals, which means they self-seed the second year, so the young plants take over for the old plants so it seems like you have a perennial bed. There are also garden foods which make seed which is so easy to harvest, store and plant that they are practically foolproof -- corn, potatoes, beans, buckwheat.

Many of these foods are ancient, and they are found in the diets of indigenous people all over the globe. They've been around forever, and people depend on them because they are reliable. No matter what the weather does or what stresses life might bring, their families will eat.

I am not a fearful person, and I don't want to be a hoarder or scarcity-minded. But I do feel concern that our world's food supply is very dependent on large systems which must operate fairly smoothly or none of us eat. My experience is that whole systems crash, or parts of them go down unexpectedly.

I feel safer, happier, and stronger when I raise fresh produce we can enjoy at home and also plant and care for backup food sources that, once they get going, will be there for us no matter what. And it's important to me to share my experiences with getting these perennial or self-renewing foods going, because we're not a nation of farmers or even Victory gardeners any more. Many of us live in cities or in the suburbs, without much growing space.

I hope my Hubs help people learn from my mistakes, find some joy in creating successes, and find a laugh when they need one. Thank you for reading this!

Flowers developing!