Infectious diseases of the respiratory system which can easily result to Pneumonia

Pathologic X-rays

The Pulmonary diseases

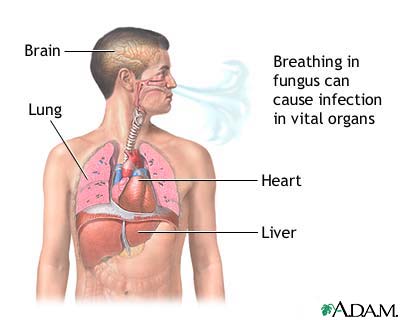

These are systemic diseases affecting the Pulmonary system due to invasive manifestation of some microbes or substances, examples of which are the systemic fungal disease, Histoplasmosis, Coccidioidomycosis, systemic Candidosis, Aspergillosis and Actinomycosis. These are very important and relevant because they all can easily be the pre-disposing factors of Pneumonia, so the ability to diagnose and treat them specifically will go a long way in the treatment of resulting Pneumonia.

SYSTEMIC FUNGAL DISEASES

(Systemic Mycoses)

General Diagnostic Principles

Several considerations are important in the diagnosis of the deep mycoses.

1. Many of the causative fungi are "opportunists," not usually pathogenic un less they enter a compromised host. Opportunistic fungus infec tions are particularly apt to occur and should be anticipated in patients after ionizing (x-) irradiation and during therapy with corticosteroids, immunosuppressives, or antimetabolites; they also tend to occur in patients with azotemia, diabe tes mellitus, bronchiectasis, emphysema, TB, Hodgkin's disease or other lymphoma, leukemia, or burns. Candidosis, aspergillosis, phycomycosis, nocardiosis, and cryptococcosis are typical opportunistic infections.

2. Fungal diseases occurring as primary infections may have a typical geo graphic distribution. For example, in the USA, cocddioidomycosis is virtually confined to the southwest, while histoplasmosis occurs in the East and Midwest. especially in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys. Blastomycosis is restricted to North America and Africa; paracoccidioidomycosis, often called South American blastomycosis, is confined to that continent. However, travelers can develop a symptomatic infection some time after returning from such endemic areas.

3. The major clinical characteristic of virtually every deep mycosis is its chronic course. Septicemia or an acute pneumonia is rare. Lung lesions develop slowly. Months or years may elapse before medical attention is sought or a diagnosis is

made.

4. Symptoms are rarely intense; fever, chills, night sweats, anorexia, weight loss, malaise, and depression may all be present.

5. When a fungus disseminates from a primary focus in the lung, the manifes tations may be characteristic. Thus, cryptococcosis usually appears as meningitis, progressive disseminated histoplasmosis as hepatic disease, and blastomycosis as a skin lesion.

6. Delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity tests and serologic tests are available for only 3 or 4 of the infections discussed in this chapter. Even in these, the tests become positive either so late (e.g., cocddioidomycosis) or so infrequently (e.g., blastomycosis) that they are of no diagnostic value for the acutely ill patient.

7. The diagnosis is usually confirmed by isolation of the causative fungus from sputum, bone marrow, urine, blood, or CSF, or from lymph node, liver, or lung biopsy. When the fungus is a commensal of man or is prevalent in his environment (e.g., Candida, Aspergjilus), it is difficult to interpret its isolation from such specimens as sputum, and confirmatory evidence of tissue invasion is necessary to attribute an etiologic role to it

8. In contrast to viral and bacterial diseases, fungal infections can be diagnosed histopathologically with a high degree of reliability. It is the distinctive fungal morphology, not the tissue reaction to the fungus, that permits specific etiologic

identification.

9. Even when the microorganism has been demonstrated histopathologically m tissues, the activity of the disease must be established before treatment is begun. Culture of the causative microorganism or such clinical and laboratory findings as fever, leukocytosis, elevated ESR, abnormal liver function, worsening of chest film findings, or elevated serum globulins are helpful as indications for therapy.

General Therapeutic Principles

General medical care, surgery, and chemotherapy constitute modes of treat ment for systemic fungus infections. Ketoconazole, a new antifungal imidazole derivative, appears to have major advantages: oral dosage, broad antifungal ac tivity, and minimal adverse effects; but testosterone synthesis may be blocked, usually transiently, and serious idiosyncratic hepatotoxidty may occur. Current usage is 200 to 400 mg orally once a day with a meal. It may be given for pro longed periods to establish and maintain clinical remission or to prevent reinfection. Because amphotericin B is used in many systemic mycoses. it is covered in detail here. Indications and directions for other therapeutic measures are given below in the discussions of specific mycoses.

Amphoteridn B, a fungicidal and fungistatic antibiotic, has reversed the progno sis of many fungal infections. An initial IV dose of 0.1 mg/kg/day is increased by 0.05 to 0.10 mg/kg every day until 1.0 mg/kg (but not exceeding 50 mg/dose) is given daily or every other day. The antibiotic is dissolved in 5% D/W (optimal concentration, 0.1 mg/ml). (CAUTION: Saline solution precipitates the drug and should not be used. Follow the manufacturer's instructions in preparing and storing solutions.)

The drug should be given over a 2- to 6-h period. Reactions are usually mild, but some patients may experience chills, fever, headache, anorexia, nausea, and, occasionally, vomiting, particularly with the initial injections. The severity of re actions may be reduced by giving aspirin or an antihistamine (e.g., diphenhydramine 50 mg) before, after 3 h, and at the end of treatment. If this therapy is ineffective, hydrocortisone 25 to 50 mg IV may be given at the beginning of the amphotericin B infusion.

Chemical thrombophlebitis may occur; adding heparin to the infusion (or into the tubing just prior to starting the injection) may lessen the incidence.

The BUN or serum creatinine should be determined before and periodically during treatment. A slight increase can be ignored. A moderate rise may be re versed by giving the drug on alternate days, but if not, treatment should be dis continued until the levels approach normal. If this requires only a few days, treatment can be resumed with the previous dose, but if a longer period is neces sary, therapy should be restarted with a smaller dose. Serum potassium should be determined regularly, since hypokalemia is common and occasionally is dramatic and dangerous. Oral liquid supplements are usually sufficient; rarely, potassium IV (not added to the amphotericin B infusion) may be necessary Intrathecal injection may be indicated in meningitis, but great care must be taken to ensure proper dose and volume: 50 mg of amphotericin B should be painstaikingly dissolved in 10 ml of sterile water. The total volume should then be diluted in a 250-ml bottle of 5% D/W from which 10 ml has been removed. From 0.5 ml (0.1 mg) to 5.0 ml (1.0 mg) should then be drawn into a 10-ml syringe, further diluted to 10 ml with CSF, and injected slowly (over at least 2 min). A lumbar, cisternal, or ventricular site may be used.

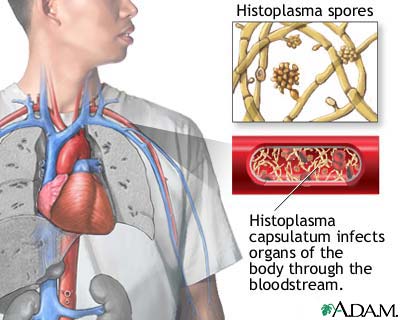

HISTOPLASMOSIS

An infectious disease caused byHistoplasma capsulatum, characterized by a pri mary pulmonary lesion and occasional hematogenous dissemination, with ulcerations of the oropharynx and GI tract, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, lymphadenopalhy, and adrenal necrosis.

Etiology and Incidence

H. capsulatum in tissue is an oval budding cell 1 to 5 ft in diameter. Infection follows inhalation of dust that contains the spores. Severe disease is more fre quent in men.

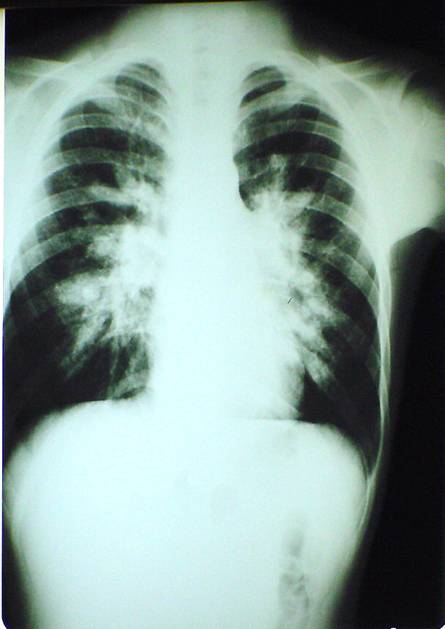

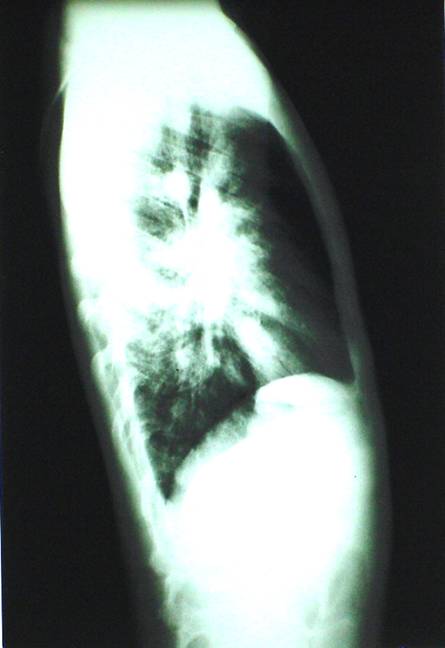

Chest x-ray (picture 7-8) surveys in certain geographic areas have demonstrated many resi dents with symptomless, nontuberculous, occasionally calcified pulmonary le sions; delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions to histoplasmin suggest widespread but subclinical infection. The highest incidence of such hypersensitiv ity is in the Ohio and Mississippi River valleys.

Symptoms and Signs

There are 3 recognized forms of the disease. The primary acute form causes symptoms (fever, cough, malaise) indistinguishable in endemic areas (except by culture) from otherwise undifferentiated URI or grippe-like disease. The progres sive disseminated form follows hematogenous spread from the lungs and is charac terized by hepatomegaly, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, and, less frequently, oral or GI ulceration. Addison's disease is an uncommon but serious manifestation. The lesions in the liver are granulomatous, show the intracellular fungus, and may lead to hepatic calcification. Addison's disease of other etiology, lymphoma, Hodgkin's disease, leukemia, and sarcoidosis must be differentiated. The chronic cavitary form produces pulmonary lesions indistinguishable, except by cul ture, from cavitary TB. The principal manifestations are cough, increasing dyspnea, and eventually disabling respiratory embarrassment. That histoplasmosis is a cause of uveitis has been postulated but not proved.

Diagnosis

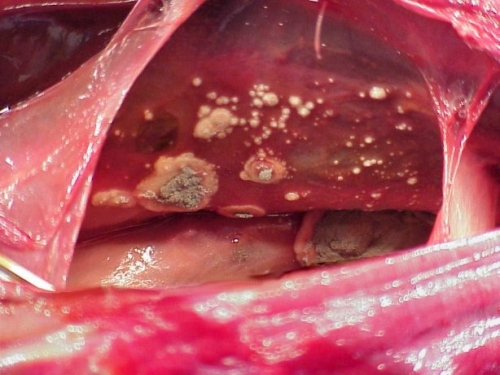

Demonstration of H. capsulatum by culture is diagnostic. Specimens for culture may be obtained from sputum, lymph nodes, bone marrow, liver biopsy, blood, urine, or oral ulcerations. Tissues may also be examined microscopically after staining (Goroori's methenamine silver, periodic add-Schiff, or Gridley) picturtes 9-10, Delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity and CF tests are of no diagnostic value, since they are usually negative early in the disease.

Prognosis and Treatment

The acute primary form is usually benign; it is fatal only in those rare cases with massive infection. The progressive disseminated form has a high mortality. In the chronic cavitary form, death results from severe respiratory insufficiency.

Primary acute disease rarely requires chemotherapy (see amphotericin B and also ketoconazole in General Therapeutic Principles, above). The disseminated form responds to amphotericin B; in the chronic cavitary form, the fungi disap pear with therapy, but fibrotic lesions show little change.

COCCIDIOIDOMYCOSIS

(San Joaquin or Valley Fever)

An infectious disease caused by the fungusCoccidioides immitis, occurring in a primary form as an acute, benign, self-limiting respiratory disease, or in aprogressive form as a chronic, often fatal, infection of the skin, lymph glands, spleen, liver, bones. kidneys, meninges, and brain.

Etiology, Incidence, and Pathology

The disease is endemic in the southwestern USA and occurs most frequently in men aged 25 to 55. Infection is acquired by inhalation of spore-laden dust. Indi viduals contracting the disease while traveling through endemic areas may not develop manifestations until later, after leaving the area.

The basic pathologic change is an acute, subacute, or chronic granulomatous process with varying degrees of fibrosis. Lesions may show central necrosis; the organisms are surrounded by lymphoctyes and by plasma, epithelioid, and giant cells. Cavitation or granuloma ("coin lesion") formation may occur in chronic lung infection.

Symptoms and Signs

Primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis, the more common form, may occur asymptomaucally, as a mild URI, as acute bronchitis, occasionally with pleural effusion, or as pneumonia. Symptoms, in descending order of frequency, include fever, cough, chest pain, chills, sputum production, sore throat, and hemoptysis. Physical signs may be absent, or occasional scattered rales and areas of dullness to percussion may be present. Leukocytosis is present and the eosinophil count may be high. Some patients develop "desert rheumatism," a more recognizable form with conjunctivitis, arthritis, and erythema nodosum.

Progressive coccidioidomycosis develops from the primary form; evidence of dissemination may appear a few weeks, months, or, occasionally, years after pri mary infection or long residence in an endemic area. Symptoms include continuous low-grade fever, severe anorexia, and loss of weight and strength. Progressive cyanosis, dyspnea, and mucopurulent or bloody sputum are present in the pulmo nary type. The bones, joints, skin, viscera, brain, and meninges may be involved as the disease spreads.

Diagnosis

Coccidioidomycosis should be suspected in a patient with anobscure illness who has been or is in an endemic area. Diagnosis is established by finding the characteristic spherules of C. immitis in sputum, gastric washings, pleural fluid, CSF, pus from abscesses, biopsy specimens, or exudate from skin lesions by direct examination or culture. In the tissues, the fungus appears as thick-walled, non-budding spherules 20 to 80 fi in diameter.

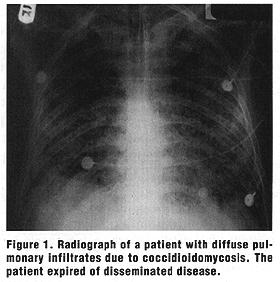

A delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity reaction to coccidioidin or spherulin usu ally appears 10 to 21 days after infection, but is characteristically absent in pro gressive disease. Precipitating and CF antibodies are present regularly and persistently in the progressive form but only transiently in acute primary cases. X ray findings are on figures 1-2.

Prognosis and Treatment

For primary pulmonary Coccidioidomycosis, treatment is not needed and the outlook is excellent. The progressive type, however, is fatal in 55 to 60% of cases. Amphotericin B (see amphotericin B and also ketoconazole in General Therapeu tic Principles, above) is indicated in all patients with the progressive form. Results are less satisfactory than in blastomycosis or histoplasmosis. Meningitis requires prolonged intrathecal administration, usually for years. Untreated meningitis is fatal.

SYSTEMIC CANDIDOSIS

(Candidiasis; Moniliasis)

Etiology and Incidence

The infections are usually caused by C. albicans. Superficial candidosis is uni versal, but patients with leukemia, or with organ transplants, or receiving immunosuppressive or antibacterial therapy are especially prone to C. spp. septicemia. C. spp. (frequently C. parapsilosis) endocarditis is related to intravascular trauma such as cardiac catheterization, surgery, or indwelling venous catheters.

Symptoms and Signs

C. spp. endocarditis resembles bacterial disease, with fever, heart murmur, splenomegaly, and anemia; large vegetations and emboli to major vessels are fre quently present and are differential features. Renal involvement is usually found on laboratory and autopsy examination. C. spp. septicemia usually resembles gram-negative bacterial sepsis in frequency of fever, shock, azotemia, oliguria, renal shutdown, and fulminant course. C. spp. meningitis is chronic, like crypto-coccal meningitis, but lacks the latter" s usually fatal outcome when untreated. C. spp. pyelonephritis and pulmonary disease are less well characterized. Osteomyelitis is rarely encountered; it resembles that due to other microorganisms.

Diagnosis

Because C. spp. are commensals of man, their culture from sputum, mouth, vagina, urine, stool, or skin must be interpreted cautiously. To confirm the diag nosis, the culture must be complemented by a characteristic clinical lesion, exclu sion of other etiology, and histologic evidence of tissue invasion. Isolation from blood or CSF, however, establishes the presence of C. spp. infection and supports the appropriate clinical impression: septicemia, endocarditis, or meningitis.

Treatment

Such predisposing conditions as diabetic acidosis must first be controlled. In systemic candidosis, amphoteridn B IV is preferable therapy. As an alternative, flucytosine may be given as for cryptococcosis (see above) if the isolate is sensitive to it. Ketoconazole appears promising in investigational studies in this disorder.

ASPERGILLOSIS

Etiology, Symptoms, and Signs

The fungus, an "opportunist," appears after antibacterial or antifungal therapy (to which it is usually resistant) in bronchi damaged by bronchitis, bronchiectasis, or tuberculosis. The "fungus ball" (aspergilloma), a characteristic form of the disease, appears on the chest film as a dense round ball, capped by a slim menis cus of air, in a cavity; it is composed of a tangled mass of fibrin, exudate, and a few inflammatory cells. Aspergillomas usually occur in old cavitary disease (e.g., tuberculosis) or, rarely, in patients with rheumatoid spondylitis. Symptoms (cough, productive sputum, dyspnea) and findings on physical examination or chest film are usually those of the underlying disease. However, hemoptysis has been a disturbing and even occasionally fatal complication. In the presence of leukemia, organ transplantation, or corticosteroid or immunosuppressive therapy, dissemination to the brain and kidneys may occur. The clinical picture in this form is a typical septicemia: fever, chills, hypotension, prostration, and delirium.

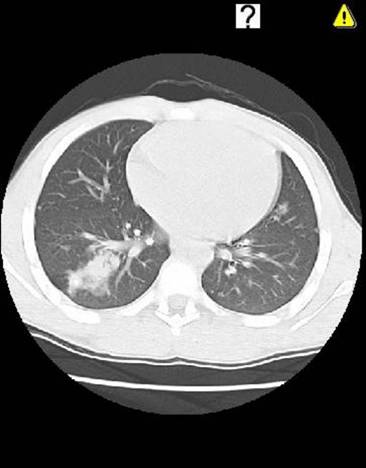

Examination of the chest films (picture 11) reveals bilateral perihilar opacities centrally extending out into the mid-lung fields bilaterally. There is a pattern resembling “hotdogs” or “V shaped clusters of grapes” radiating from the hilus. This pattern is due to impaction of the bronchus by viscid secretions containing aspergillus hyphae. Dilation occurs distal to the bronchial plugs creating bronchiectasis which can be demonstrated by bronchography. Clinically, two primary presentations of allergic aspergillosis may be encountered. The disease may be superimposed upon life-long asthma, or may be an etiologic factor in the development of asthma in patients late in life. In addition to the presence of asthma and asthmatic attacks, the patients almost invariable have peripheral blood eosinophilia, fever, and a rather characteristic chest roentgenogram.

This condition responds dramatically to steroid therapy as steroids act to decrease host overresponsiveness, allowing bronchial edema to resolve.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Because it is a commensal of man, culture of A. spp. from sputum, mouth, or bowel must not be considered diagnostic unless a clinically compatible illness is present, other causes have been eliminated, and tissue invasion has been demon strated. In disseminated and pulmonary disease, amphotericin B should be given IV although tolerated doses are usu ally ineffective, since most strains are resistant.

ACTINOMYCOSIS

(Lumpy Jaw)

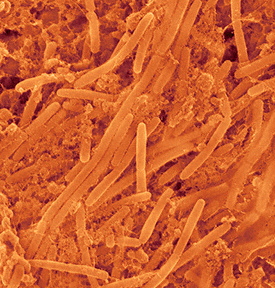

A chronic infectious disease characterized by multiple draining sinuses and caused by the anaerobic gram-positive microorganism Actinomyces israelii, often present as a commensal on the gums, tonsils, and teeth.

Incidence and Pathology

The disease is seen most often in adult males. In the cervicofacial form, the rnost common portal of entry is decayed teeth; pulmonary disease results from aspiration of oral secretions; abdominal disease, from a break in the mucosa of a diverticulum or the appendix.

The characteristic lesion is an indurated area of multiple, small, communicating abscesses surrounded by granulation tissue. Disease spreads to contiguous tissue and, rarely, hematogenously. Other anaerobic bacteria are usually also present.

Symptoms and Signs

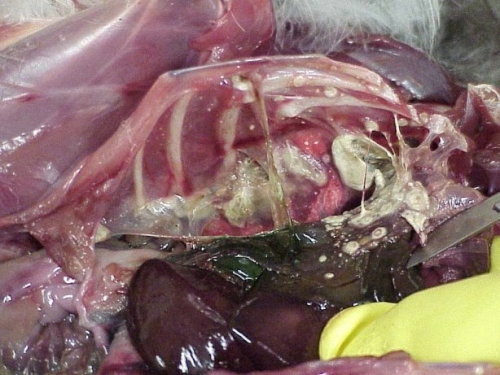

There are 4 clinical forms of actinomycosis. (1) The abdominal form affects the intestines (usually the cecum and appendix) and the peritoneum. Pain, fever, vomiting, diarrhea or constipation, and emaciation are characteristically present. An abdominal mass with signs of partial intestinal obstruction appears, and draining sinuses and fistulas may develop in the abdominal wall. (2) The cervicofacial form usually begins as a small, flat, hard swelling, with or without pain, under the oral mucosa or the skin on the neck, or as a subperiosteal swelling of the jaw. Subsequently, areas of softening appear and develop into sinuses and fistulas with a discharge that contains the characteristic "sutfur granules" (rounded or spherical, usually yellowish, granules up to 1 mm in diameter). The cheek, tongue, pharynx, salivary glands, cranial bones, meninges, or brain may be affected, usually by direct extension. (3) In the thoracic form, involvement of the lungs resembles TB. Extensive invasion may occur before chest pain, fever, and productive cough appear. Perforation of the chest wall, with chronic draining sinuses, may result. (4) In the generalized form, hematogenous spread occurs to the skin, vertebral bodies, brain, liver, kidney, ureter, and (in women) the pelvic organs.

Diagnosis

This is based on clinical symptoms, x-ray findings (picture 12), and demonstration of A. israelii in sputum, pus, or biopsy specimen. In pus or tissue, the microorganism appears as tangled masses of branched and un-branched wavy filaments, or as the distinctive "sulfur granules." These consist of a central mass of tangled filaments, pus cells, and debris, with a midzone of interlacing filaments surrounded by an outer zone of radiating, club-shaped, hya line and refractive filaments that take the eosin stain in tissue.

Lung lesions must be distinguished from those of TB and neoplasms. Lesions in the abdomen occur most frequently in the ileocecal region and are difficult to diagnose, except at laparotomy or when draining sinuses appear in the abdominal wall. Aspiration liver biopsy should be avoided because of me danger of inducing a persistent sinus. A tender, palpable mass suggests appendiceal abscess or regional enteritis. Nodules in any location may simulate malignant growths.

Clinical presentation:

53 year old man with left side pain and a lump in the left axilla, dullness to

percussion in the left lower chest. Had been treated for an infection 3 and 25

years before. Works as a fitter, cutting insulation by hand. Smokes 10

cigarettes a day.

The view is taken central. The size of the left lobe is reduced and the margins of left hemidiaphragm, the lower left heart margin and the costophrenic recess are obscured by a density that has a clear central margin as it extends into the left axilla, implying a pleural density. There is shadowing at the apex of both lungs. This is well-defined and irregular with calcifications. The right hilar vessels are vertical and sparse in both upper zones with elevation of the hilar point on both sides, implying loss of upper lobe volume. There is coarse linear calcification immediately above the diaphragm, well shown on the right and a little obscured on the left. In this particular view, no rib erosion is identified.

Prognosis and Treatment

The disease is slowly progressive. Prognosis relates directly to early diagnosis, is most favorable in the cervicofacial form, and is progressively worse in the pulmo nary, abdominal, and generalized forms.

Most cases will respond to medical treatment but, owing to the extensive indu ration and relatively avascular fibrosis, response is slow and treatment must be continued for at least 8 wk and occasionally for > 1 yr. Extensive and repeated surgical procedures may be required. Aspiration is indicated for small abscesses and drainage for large ones. Penicillin G, at least 12 million u./day IV, should be given initially; penicillin V 1 gm orally q.i.d. may be substituted after about 2 wk. Tetracycline 500 mg orally q 6 h may be given instead of penicillin. Treatment must be continued for several weeks after apparent clinical cure.

Clinical pictures of these diseases

Contributors and acknowledgement

Medical treatment

Fungal Pathogen: Histoplasmosis

Indication for Antifungal Therapy: Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis with hypoxia; prolonged moderate symptoms for more than 1 month; disseminated disease; immunosuppressed host

Mortality rate for untreated disseminated disease at 80%; reduced to 25% with treatment

Surgical Care and Other Treatments: Significant hemoptysis; recurrent pneumonia; repair of bronchopleural fistula

Corticosteroids in severe hypoxia

Anti-inflammatory agents to treat rheumatologic syndromes

Antifungal Drugs Used: Amphotericin B induces rapid response in patients who are severely ill

Azoles/triazoles in patients with milder illness

Fungal Pathogen: Coccidioidomycosis

Indication for Antifungal Therapy: Disseminated disease; chronic pulmonary disease; acute pulmonary infection with hypoxia or protracted morbidity (>1-2 mo); immunosuppressed host (worst outcome, 70% mortality).

Surgical Care and Other Treatments: Surgical debridement or resection of infective tissue often necessary adjunct to antifungal treatment

Anti-inflammatory agents for rheumatologic syndromes

Antifungal Drugs Used: Amphotericin B effective in more than 90% of cases

Fluconazole or itraconazole after improvement

Treatment less effective than in other endemic mycoses

Fungal Pathogen: Blastomycosis

Indication for Antifungal Therapy: Persistent or recurrent symptoms of acute or chronic pulmonary disease or with pleural involvement; disseminated disease.

Surgical Care and Other Treatments: N/A

Antifungal Drugs Used: Amphotericin B response rates of 77-90%

Itraconazole successful in 90%

Ketoconazole response of 80%; poor outcome in patients who are immunosuppressed

Fluconazole less effective, 65% response rate

Chronic maintenance treatment essential for all patients with AIDS or meningitis

Fungal Pathogen: Cryptococcosis

Indication for Antifungal Therapy: Patients who are immunosuppressed and symptomatic; patients who are immunocompetent with disease progression; any patients with meningitis or disseminated disease

Surgical Care and Other Treatments: N/A

Antifungal Drugs Used: Amphotericin B in patients who are severely ill

Fluconazole in milder cases or after clinical response to amphotericin B

Lifelong maintenance therapy in AIDS patients because of frequent recurrences when treatment stopped

Fungal Pathogen: Aspergillosis; mucormycoses

Indication for Antifungal Therapy: All patients with invasive disease; in patients who are immunosuppressed, early diagnosis and empiric treatment for persistent fever not responding to broad-spectrum antibiotics; high mortality once infiltrates and symptoms appear; prognosis ultimately linked to severity and outcome of underlying disease

Mortality rate of 50-60% in patients with AIDS; mortality rate as high as 85% in patients with prior bone marrow transplantation

Surgical Care and Other Treatments: Aggressive surgical debridement of necrotic tissue important in mucormycosis, especially if confined to lungs

Rapid tapering of immunosuppressive agents and corticosteroids and reversal of neutropenia (if possible)

Antifungal Drugs Used: Voriconazole is the new standard of care for invasive aspergillosis based on superiority over amphotericin B in primary therapy

Lipid formulations of amphotericin B have at least equal efficacy but less toxicity compared with amphotericin B desoxycholate

Oral voriconazole can be used to complete treatment with initial response to IV voriconazole or amphotericin B;Mucor species generally resistant to azoles

Caspofungin useful as salvage therapy

Fungal Pathogen: Candidiasis

Indication for Antifungal Therapy: All patients with invasive disease or dissemination; important to reverse factors affecting immune status

Surgical Care and Other Treatments: Rapid tapering of immunosuppressive agents and corticosteroids; important to remove indwelling infected intravenous lines or urinary catheters in setting of hematogenous spread

Antifungal Drugs Used: Amphotericin B is mainstay

Flucytosine may be of benefit when added to amphotericin B

Fluconazole use in pulmonary disease not studied but is effective in hepatosplenic candidiasis and candidemia

Echinocandins may be useful alternatives