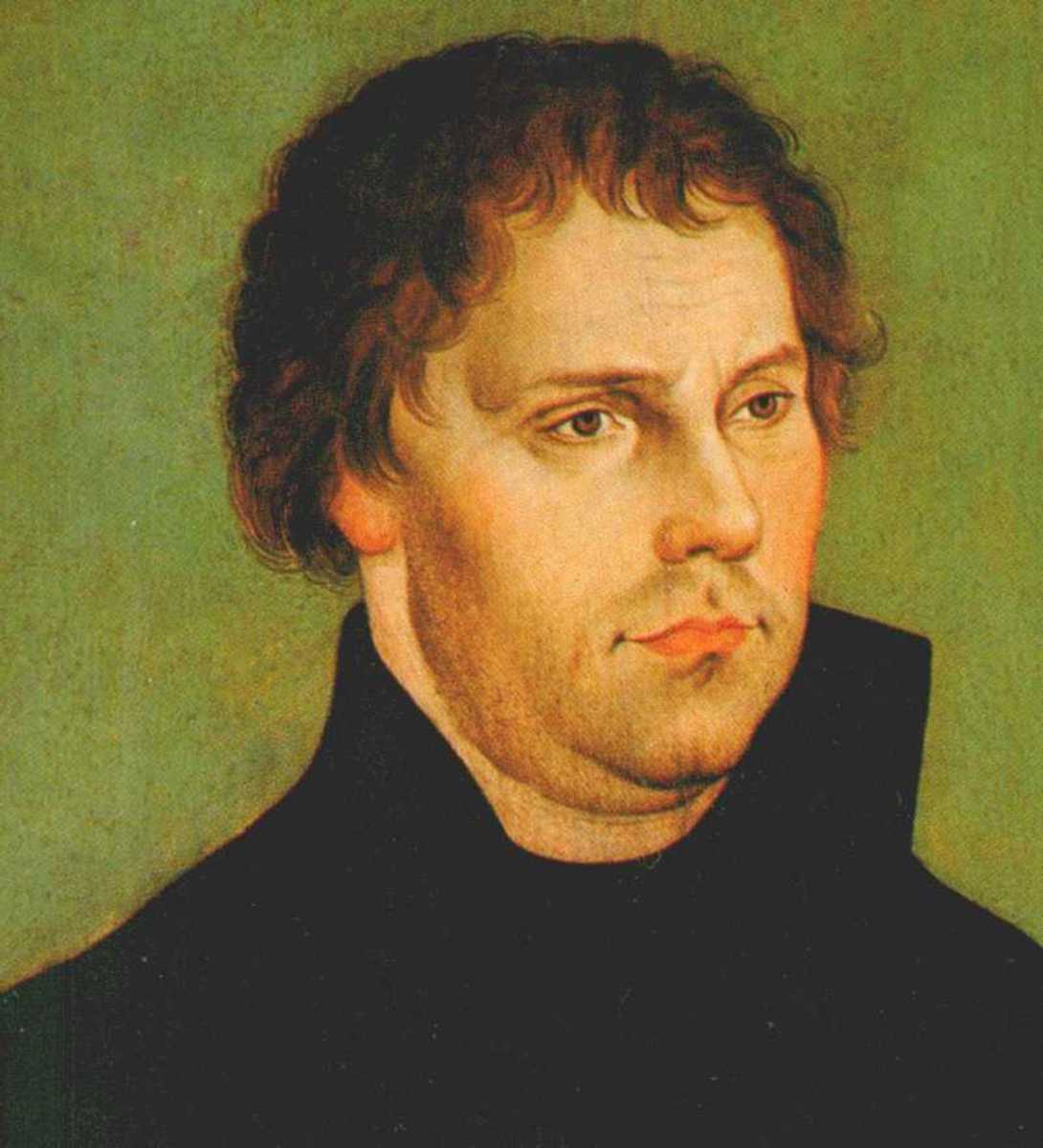

Martin Luther, Henry VIII, and the Practical Factors that Helped Shape Early Protestant Bibles

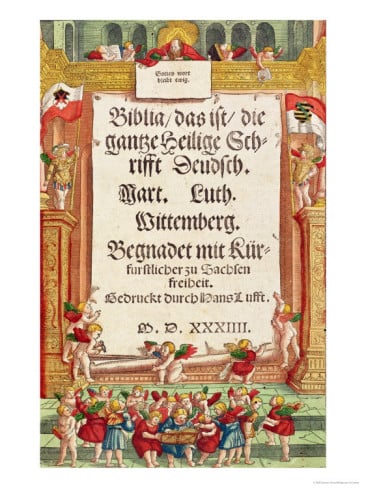

Confronted with the Luther Bible for the first time, readers are faced with a bit of a quandary. Poring over the grand title page, the beautiful and elaborate illustrations, Luther’s own introduction, and the marginal notes,[1] one wonders how such a Bible could have been produced by a man of Luther’s theology. Famous for his sola scriptura doctrine, which held that holy scripture alone— rather than church authorities and the interpretations they produced— held the keys to salvation, Luther advocated for a movement away from church-guided readings of the holy text, favoring instead a deeply personal, individual relationship with the divine based on universal, unmitigated access to the holy word. [2] Thus he produced a highly accessible Bible, rendered in the vernacular and stripped of its usual accompanying gloss. Yet neither this Bible nor its immediate Protestant successors, with their own illustrations and paratextual material, provide truly unmitigated access to the scriptures. In Luther’s case, this inconsistency may perhaps be traced to practical concerns: the need to reach a broad, perhaps sometimes semi-literate audience, the influence of manuscript tradition on early print culture, and the difficulties of translation. For later Protestant Bibles, such as the English Great Bible of Henry VIII and the Geneva Bible, political agendas are clearly at work. Because of this, early Protestant Bibles may perhaps reasonably be seen as a study in the many practical, extraneous factors that— in addition to pure theology— helped to shape the Protestant Reformation and the offshoots of Christianity that it would produce.

Beginning with the Luther Bible, one can easily observe that some of the extraneous influences preventing Bibles from being presented in what Luther might in theory consider their ideal form— as the word of God, unaltered and un-supplemented by any outside authority— were merely practical inevitabilities. Perhaps most obviously, Luther’s desire to reach as broad an audience as possible prevented him from presenting an entirely “pure” text, free from alterations or interpretive aids. As only the very most educated German speakers could read Hebrew, Greek, and Aramaic, the text had to be translated. As only a minority of Germans were completely fluent readers, the text had to be presented in an accessible manner, with decorated letters, illustrations, and other embellishments added as aids to help unsteady readers navigate and interpret the text. Therefore, committed as Luther was to limiting the interference of the church hierarchy with the Christian reader’s experience, he necessarily had to interfere to some extent in order to enable the common reader to have any meaningful reading experience at all. One might even say that Luther’s commitment to providing all people with direct access to the scriptures paradoxically necessitated alteration and supplementation of said scriptures, which actually precluded the possibility of the kind of direct access he was trying to facilitate. The sola scriptura ideal was just not practically achievable in Luther’s time— or even our own. Despite modern literacy rates, translation of the holy text is still a necessity for the vast majority of readers, and the sheer materiality of the text means that editorial decisions regarding its formatting and presentation will always bear some influence on readers’ interpretation. No pure, ideal Bible does— or even can— exist.

Delving more deeply into some of these issues, we can see that Luther himself seems to have acknowledged the practical difficulties of presenting readers with the unmitigated word of God. Although his statements at times seem to contradict one another, the most coherent picture that emerges upon reading his early writings and sermons together is of a Luther committed to the importance of the written word not as perfect and divinely inspired, but as a necessary vehicle for the communication of the gospel, the good news of Christ’s gift of salvation to the faithful which Luther situated as the “center” of the holy text.[3] In “The Gospel for the Festival of the Epiphany,” a sermon produced during his seclusion in Wartburg Castle from 1521-2, Luther complained: “But that books even have to be written is already a great detriment and a weakness of the spirit, which has been forced by necessity.”[4] Quotations such as this one have been taken by many scholars to illustrate Luther’s preference of the “living voice” or viva vox of preaching over the written text,[5] an interpretation that seems to be supported by his 1520 statement that “One notes that Christ did not write; instead, he spoke everything; the apostles wrote little; mostly they spoke.”[6] However, Luther’s insistence upon the radical move of producing a vernacular Bible free of its usual accompanying authoritative gloss— along with the sheer fact that he was a prolific enough writer to single-handedly transform Wittenberg into a major publishing center[7]— seems to preclude the possibility that Luther entirely disregarded the importance of the written word, subordinating it to preaching. In fact, in his later work, Tischraden, he wrote that “Printing is the ultimate gift of God and the greatest one” because of its ability “to spread word of the cause of the true religion to all of the Earth, to the extremities of the world.”[8] These seemingly contradictory views are perhaps best reconciled by referring to a final quotation from Luther: “If it were helpful to express wishes, it would be best of all to wish that, to put it bluntly, all books would be destroyed and that throughout the world, especially for Christians, nothing else would remain but the plain, pure Scripture or Bible.”[9] While Lutheran pastor and theologian Oswald Bayer writes that this quotation illustrates Luther’s commitment to the holy scripture above all other texts— and the Catholic standard gloss, which compose the mass of books the reformer believed might best be destroyed,[10] even this assertion seems odd coming from a man who spent much of his life publishing a massive oeuvre of theological works and religious propaganda. It should also be noted that even though this quotation does seem to condemn supplements to the Bible, Luther’s own Bible employs an introduction and sparse, but present marginal notes, along with spectacular accompanying illustrations. In light of this, a slightly different interpretation of Luther’s views on the written word seems to be in order. Referring to Bayer and fellow theologian Richard Soulen’s accounts of Luther’s theology, we might instead focus on Luther’s desire for a “pure” scripture to suggest that Luther saw the written word as an imperfect but necessary medium for communicating the grace of God to humankind. Since imperfect beings— perhaps because of some “weakness of the spirit”— require some practical, material aid to bring them to Christ rather than accessing him directly, the scripture must be bound to the imperfect, physical world through conveyance by an imperfect, physical medium.

According to Richard Soulen, one of the major differences between Luther’s theology and that of the contemporary Catholic Church could be found in where Luther located the “center” of scripture. Whereas previous theologians had considered the word of God to be an account of history, laws, and God’s justice—meaning his just retribution against evil, Luther believed that the center of scripture was the good news of the gospel.[11] According to Luther, God’s law and justice were ideas that could be understood instinctively or reasoned out by anyone possessing intelligence and a sound conscience. In other words, mundane morality did not require the scripture to be taught; it was something that humans naturally understood and was thus not unique to the scripture or even to Christianity. Conversely, only the scriptures told the good news of Christ’s sacrifice and resurrection, a more specifically Christian doctrine that required faith to be accepted.[12] Because of this, Luther defined scripture not as the text or information found in the books long considered to compose the Bible, but simply “what inculcates Christ.” According to him, “Whatever does not teach Christ is not yet apostolic, even though St. Peter or St. Paul does the teaching. Again, whatever preaches Christ would be apostolic, even if Judas, Annas, Pilate, and Herod were doing it.”[13] To reflect this ideal, Luther even changed the order in which he included the books of the New Testament in his own edition, moving the Epistle of James—a gospel-less text that he famously considered to be “an epistle of straw”—along with Hebrews, Jude, and Revelation, to the back of the volume.[14]

We can easily see, based on these ideas, that Luther considered the scripture a vessel for the delivery of Christ to the faithful. This much he more or less explicitly states in his preface to the Old Testament, writing that the text constitutes “the swaddling cloths and the manger in which Christ lies… Simple and lowly are these swaddling cloths, but dear is the treasure, Christ, who lies in them.”[15] The language Luther uses to describe scripture—or at least the Old Testament—illustrates both his reverence for their precious contents and a belief that the written word is a “simple and lowly,” but necessary medium for communicating them. Luther’s discussion of the work of translating the bible into the German vernacular may be seen as consistent with this idea, as he complained that “I bleed blood and water to give the Prophets in the vulgar tongue. Good God, what work! How difficult it is to force the Hebrew writers to speak German! Not wishing to abandon their Hebrew nature, they refuse to flow into Germanic barbarity. It’s as if the nightingale, losing its sweet song, was forced to imitate the cuckoo and its monotonous note.”[16] Champion of the vernacular that he was, Luther understood the difficulties of preserving the poetry—and perhaps even the exact meaning—of a text when translating it into a different language. Therefore, he did not speak of the process in the words of a man who believed that he was communicating the divinely inspired, unadulterated word of God to the German people, but in the words of a frustrated craftsman, attempting to patch together a suitable conveyance for the divine gospel in spite of the practical constraints he faced.

Perhaps it is partially because of his awareness of these difficulties that a later Luther would, as Roger Chartier notes “abandon… his insistence that every Christian should know how to read the Bible,” instead favoring preaching as the ideal means of communicating the gospel to the masses.[17] Preaching neatly avoided some of the dilemmas that might arise from exposing a less-than-educated reader to a necessarily imperfect vernacular translation of the Bible, and it allowed the preacher to personally carry out the kind of guidance and explication for his congregation that the illustrations in the Luther Bible were perhaps intended to perform for common readers. However, as with the illustrations, this guidance might seem uncomfortably similar to the Catholic glosses that Luther opposed, indicating that practical concerns—about the reading ability of the average Christian, the appropriateness of reading for common audiences, the difficulty of communicating with such audiences, and their minimal understanding of nuances such as the challenges of translation—caused tension between ideal Lutheranism and Lutheranism as it came to be practiced. While Luther’s principles, particularly as expressed in his early writings and sermons, support doctrines like the primacy of direct access to pure scripture and a priesthood of all believers, rather than reliance on paratextual additions and the interpretational assistance of a formal ecclesiastical hierarchy, in practice the fulfillment of these principles seems to have been near-impossible, pushing Luther to compromise and to hedge his position at least slightly over time.

In addition to the direct evidence we have that Luther was aware of complications arising from the materiality of printed scripture— and the compromises it occasioned, chronological distance allows us to contextualize the Luther Bible within its historical moment, thus placing a modern reader at the ideal vantage point for noticing the impact of early print culture and manuscript tradition on the development of early Protestant bibles, an influence of which Luther and his contemporaries may not have been entirely aware. While modern bibles, in keeping with the conventions of modern printing and the habits of modern readers, tend to be printed in relatively unadorned Roman type, with chapter and verse numbers included and minimal or no illustration, the Luther Bible modeled itself— consciously or not— on manuscript and early print predecessors. While the choice to print the Bible in the German vernacular and without the standard gloss was a radical break from tradition, in many ways— including large size, decorated letters, illustrations, and marginal notes— the Luther Bible resembles its medieval and early modern Catholic forebears far more than it does the Protestant bibles of today.

Perhaps most obviously, the sheer size of the massive, two-volume Luther Bible sets it apart from the modern King James Bibles found in the pews of many present day Protestant churches. This imposing heft seems to help establish it as part of a tradition of large and ornate lectern bibles, often used for preaching or for reading aloud in groups. It is interesting to note that, although at the time that Luther translated this bible he had not yet begun to stray from his belief that all Protestants should be able to read the holy text, the size of the book still makes it ideal for preachers or out-loud readers guiding a group. While there may be practical reasons for deliberately making this choice in spite of Luther’s commitment to individual reading among the faithful— such as the desire to accommodate illiterate listeners, to lend the text gravitas through its literal weight, or to attract customers by offering the kind of large and impressive tome previously only available to the wealthy in the manuscript era of the recent past—it seems that the Luther Bible, in imitating large and ornate predecessors, promoted preaching over private readership long before its creator did.

Similarly, the illustrations and marginal notes included in the bible may be seen either as consciously included to aid or attract the common reader or as vestiges of the manuscript and biblical print conventions from which the Luther Bible is descended. While the included illustrations do serve to assist semi-literate readers or perhaps communicate something of the meaning of the text to completely illiterate viewers, they also place the Luther Bible within the longstanding tradition of viewing bibles as art objects. Dating back to the Middle Ages, gospel books such as the famous Book of the Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels had been spectacularly decorated. Often the illustrations served as a practical explicatory supplement to the text, and their intricacy and illumination served as an object of wonderment to potential converts. Along with the relics, pictures, and panel paintings displayed by missionaries, they communicated the power, wealth, and beauty of the new religion even to those who could not read the text.[18] Although Luther’s theology deemphasized the church hierarchy, pulling away from ostentatious displays of wealth and emphasizing connection with the biblical text itself—or at least its preaching—as necessary to salvation, the Luther Bible can be seen as in some ways remaining very much a part of this older tradition. Although the illustrations—perhaps out of practical, monetary concern—are merely black and white woodcuts, they are rendered in meticulous detail far surpassing the ornamentation most people would have been able to afford to add to texts in the manuscript age. Wealthy customers also likely had them embellished with color or even gold. For example, Stephen Fuessel’s facsimile of the Luther Bible renders each woodcut in gorgeous color, including shades of red, blue, green, yellow, and coral, along with the occasional use of gold leaf.[19] Although Luther would have had no control over the embellishments added by wealthy readers, the existence of such ornately decorated copies of the Luther Bible perhaps show that—in spite of principles which seem to have been more in line with opposition to textual adornment—early Protestants perhaps wanted to own beautiful bibles more firmly connected to the tradition of their Catholic predecessors than they may have realized.

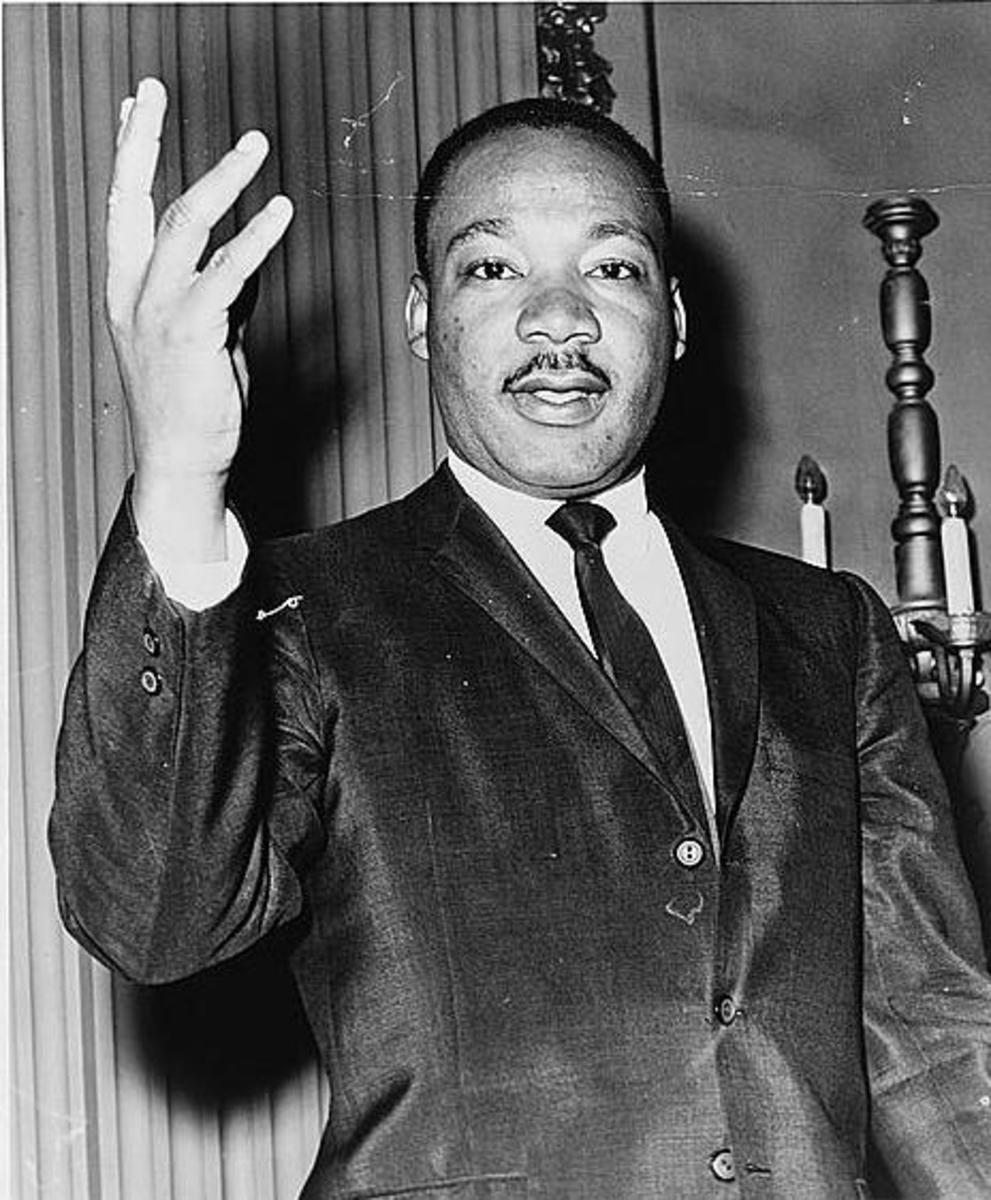

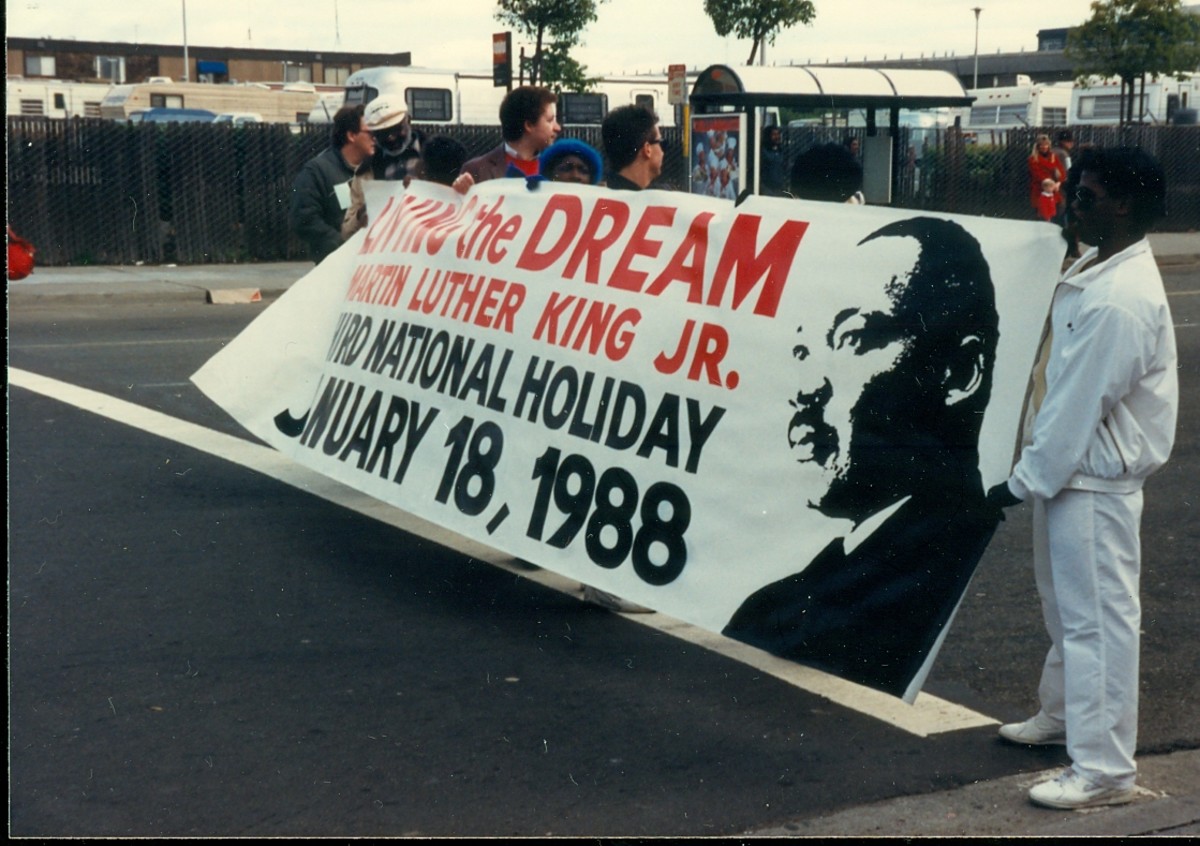

Moving beyond Martin Luther, we can also observe that later Protestant Bibles were similarly deeply influenced by practical factors. In fact, the case of two popular early English Protestant bibles, The Great Bible endorsed by Henry VIII and The Geneva Bible popular in the time of Elizabeth I, helps to illustrate that later Protestant bibles— along with Protestant theology— were influenced not only by practical inevitabilities and a perhaps unconscious adherence to historical tradition, but by conscious, deliberate political manipulation. While both texts included the kinds of woodcuts and interpretive aids already previously included in the Luther Bible, they also unabashedly worked to advance the agendas of their authors and endorsers. Even the now famous King James Bible widely used today participated in this political grasping by attempting to replace the Calvinist-slanted Geneva version which James I held to be “very partiall, vntrue, seditious, and sauouring too much of daungerous and trayterous conceites.”[20] Perhaps it is a telling illustration of the political influences on early modern English bible production that the King James Bible is named for a monarch rather than a location, philosophy, or theologian.

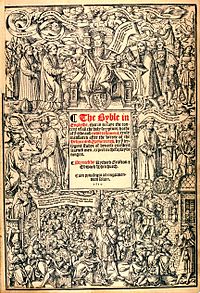

Like the Luther Bible, the Great Bible of Henry VIII begins with a fabulously detailed woodcut illustrating the transmission of the word of God to the people. However, there are a few crucial and highly informative differences between the two images. First, the title page of the Luther Bible shows a bearded man writing in the center of the uppermost portion of the image, situated above a banner whose text reads “Gottes wort bleibt ewig” or “The word of God is forever,” the implication apparently being that the figure we see is God setting down the gospel for mankind. Below him, cherubs gather around a central angel reading from a book, presumably the one written by God. Published five years later, the Great Bible also features a bearded figure in the upper central portion of the image. However, this figure is not God, but Henry VIII. Although upon closer inspection, one does notice a small and unobtrusive rendering of Jesus featured in the background behind him, the king is clearly the focal point of the image. To the left, he passes on a book labeled “VERBVM DEI” or “THE WORD OF GOD” to a tonsured figure, Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, identifiable by his coat of arms. Below this, the archbishop passes the book on to a kneeling priest, and in the lower left, we see a preacher speaking to a crowd, completing the final step of communicating the text orally to the common people. In the upper right, Henry’s other hand passes another book containing the “VERBUM DEI” to his chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, also identifiable by his coat of arms. Below this, Cromwell passes the book to a state official, who is seen in the bottom right portion of the image speaking to a group of citizens. Further establishing Henry’s centrality to the image, both the congregation and the citizens are surrounded with flourishing banners alternately reading “VIVAT REX” or “GOD SAVE THE KYNGE.”[21] From this image alone, it seems clear that the Great Bible, although similar in many ways—including its “great” size, included preface, and woodcuts—to the Luther Bible, employed these similarities in pursuit of a separate agenda. Whereas images and other devices were included in the Luther Bible as interpretational aids or perhaps vestiges of an older tradition, the images in Henry VIII’s Great Bible were clearly intended to sway the interpretation of readers in a way that was politically advantageous to the monarchy. Rather than using its title image to bring our attention to the divine origins of the text, the Great Bible firmly asserts that the holy text is distributed by monarchical authority, which presides over both church and state—with even Jesus arguably shown as a peripheral, background figure, positioned above but also apparently far behind, the king.

Finally, the Geneva Bible contains supplements both educational and political. Printed only two years after the ascension of Elizabeth I, the text begins with a title page illustrating the Jews’ escape from Egypt across the Red Sea, perhaps a situation with which Protestant supporters of the queen identified after the death of her Catholic sister Mary.[22] In particular, English Protestants living in exile at Geneva would have reason to identify with God’s chosen people escaping persecution by crossing the sea. Supporting this interpretation, the image is flanked with bible passages on each side, including one not found in Exodus, but in Psalms 34:19: “Great are the troubles of the righteous, but the Lord deliuereth them out of all.” This focus on the theme of God’s deliverance of “the righteous” rather than captions related to the specific tale illustrated suggest that we are perhaps right to interpret the image metaphorically.

However, unlike in the Great Bible, whose title page shows the masses educated not through their own private reading, but through the preaching of authorities, the Geneva Bible seems to share the Luther Bible’s investment in placing the power to read and interpret scripture in the hands of the common people. This can be seen in its subtitle: “With Moste Profitable Annotations upon all the hard places, and other things of great importance as may appeare in the Epistle to the Reader.”[23] As these words suggest, the Geneva Bible is perhaps comparable to a modern day study bible, with its contents including prefatory summaries of biblical books, woodcuts— including maps, and chronological tables to aid in the reader’s study. Additionally, the text was printed in “eye-saving” Roman font rather than heavy gothic print and was also sold in quarto form, [24] making it conveniently portable for individual readers, rather than practically necessitating a lectern, therefore implying that the majority of participants in its use would be listeners. Although these supplements perhaps no more reflect the sola scriptura ideal of Martin Luther than his own, hardly un-supplemented edition, they do seem to be more clearly and deliberately intended to aid readers in individual study of the bible. Therefore, although the book celebrates the ascension of a Protestant ruler to the throne, it does not emphasize her authority over the church—and even the bible itself—as explicitly as its predecessor, the Great Bible. Rather, it represents an admirable attempt at democratizing access to the scriptures unseen even in the Luther Bible.

Perhaps this democratization of the Bible is part of the reason for King James’s later opposition to the text in support of his own, largely unannotated King James version, or perhaps, as Richard Soulen suggests, the king objected to the “increasingly Calvinist slant” of its marginalia as they were supplemented and changed over the years. [25] Either way, the eventual rise of the King James Bible as the most widely read English Protestant Bible changed the course of history, perhaps providing the strongest evidence for the substantial impact of practical print decisions and politics over the development of Protestant Christianity. According to the English Bible historian David Daniell, the eclipsing of the Geneva Bible by its successor amounted to a “cultural tragedy.” Where the Geneva version had been a “masterpiece of Renaissance scholarship and printing and Reformation Bible thoroughness,” the “backward-looking, increasingly Latinist, often baldly unhelpful KJV” limited its readers by flatly providing a single translation with no supplementary material, leading to the impression that there was only one correct interpretation of the text—the literal acceptance of the King James translation as the “inerrant and literal word of God.”[26] From the Luther Bible to the later Great Bible, the Geneva Bible, and the familiar King James, tracing the many extraneous practical and political factors that went into producing each text—rather than relying on purely theological explanations—can greatly help to inform our reading not only of Protestant Bibles, but of the Protestant Reformation itself.

[1] Martin Luther, Biblia das ist die Ganze Heilige Schrifft Jeudsch, ed. Stephen Fuessel (Wittenberg: Hans Lufft, 1534; facsimile, New York: Taschen, 2003 ).

[2] Richard Soulen, Sacred Scripture: A Short History of Interpretation (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2009), 117-9.

[3] Soulen, Sacred Scripture, 114-6.

[4] Luther, “The Gospel for the Festival of the Epiphany” (1521-2). Quoted in Bayer, 2008, 78.

Oswald Bayer, Martin Luther’s Theology: A Contemporary Interpretation, trans. Thomas H. Trapp (Grand Rapids:

Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2008), 78.

[5] Bayer, Luther’s Theology, 2008, 77.

[6] Luther, Operationes in Psalmos (1520). Quoted in Bayer, 2008, 78.

[7] Andrew Pettegree, “Book Town Wittenberg” in The Book in the Renaissance (New Haven: Yale UP, 2010), 91-106

[8] Luther, Tischreden (1567). Quoted in Gilmont, 1999, 213.

Jean-Francois Gilmont, “Protestant Reformations and Reading” in A History of Reading in the West, eds. Guglielmo Cavallo and Roger Chartier (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999), 213-37.

[9] Luther, “Gospel for the Festival of the Epiphany,” Quoted in Bayer 2008, 79.

[10] Bayer, Luther’s Theology, 2008, 79.

[11] Soulen, Sacred Scripture, 115.

[12] Ibid, 119.

[13] Luther, Quoted in ibid, 115.

[14] Ibid, 119.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Luther, Quoted in Gilmont, “Protestant Reformations and Reading,” 219.

[17] Roger Chartier, “The Practical Impact of Writing” in The Book History Reader, eds. David Finkelstein and Alistair McCleery (New York: Routledge, 2002), 119-42.

[18] Christopher DeHamel, “Books for Missionaries” in A History of Illuminated Manuscripts (London: Phaidon, 1986), 14-41.

[20] James Stuart, Quoted in Soulen, Sacred Scripture, 50-51.

[21] Miles Coverdale, The Byble in Englyshe, that is to say the content of all the holy scripture, bothe of y olde and newe testament, truly translated after the veryte of the hebrue and Greke textes, by y dylygent stydye of dyuerse excellent learned men, expert in theforsayde tonges (London: Rychard Grafton and Edward Whitchurch, 1539); facsimile reprinted in Donald L. Brake, A Visual History of the English Bible: The Tumultuous Tale of the World’s Bestselling Book (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2008), 135.

[22] The Geneva Bible: A Facsimile of the 1560 Edition, ed. Lloyd E. Berry (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press: 1969).

[23] Ibid.

[24] Soulen, Sacred Scripture, 50.

[25] Ibid.

[26] David Daniel, Quoted in Ibid, 51.