- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Americas»

- American History

Resilient Explorer: Sacajawea

Sacajawea and Pompy

![By Hans Andersen (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons By Hans Andersen (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://usercontent1.hubstatic.com/8816136.jpg)

Slave, Child Bride, Hero

Who would have thought that the fate of thirty-four men and the success of a continent-spanning expedition would hinge on one teenaged girl?

Sacajawea certainly didn’t. Born into the Lemhi Shoshone or Snake tribe of Native Americans located in Idaho, twelve year old Sacajawea’s life seemed to be content until that horrific day when enemy Hidasta warriors raided her village. The raid resulted in four Shoshone men, four women and a handful of young boys slaughtered while Sacajawea and several other girls were grabbed by the attackers and carried away. Sacajawea and the other girls were brought to the Hidasta village in North Dakota, where she lived as a slave.

One year later, a fur trader from Quebec arrived in the Hidasta village. His name was Touissant Charbonneau, and he was a great, unclean thug of a man—he had already been stabbed once for raping a Native American woman while working for the North West Company trading furs. Unfortunately for Sacajawea, when Charbonneau came to the Hidasta village he either purchased her or won her while gambling. She, along with another woman named Otter Woman, were now his wives, and he took them away.

By 1804, Sacajawea, Otter Woman and Charbonneau settled in an outpost in North Dakota. By now, Sacajawea was sixteen and pregnant with her first child, and probably had no reason to think that her life could ever improve.

That’s when a large group of American men arrived, led by Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

As it turned out, half a world away, the French dictator Napoleon Bonaparte was in a bind; in order to continue his conquest of Europe, he needed money to finance his army … money that was rapidly draining out. At this point, France still owned all of the land west of the Mississippi River in North America, and, sure that he was never going to use that territory anyway, Napoleon made an offer to the American president Thomas Jefferson to sell him all of that land. Jefferson immediately agreed, and overnight doubled the size of the United States.

Still, the majority of the new territory had never been explored, and many were convinced that there was some kind of waterway that would connect the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific—a Northwest Passage—that would make it faster for ships to travel instead of having to circumnavigate the dangerous way around South America. Finding that passage would make the United States rich, and mapping the terrain would help determine future settlements … plus, Jefferson was an amateur scientist and was dying to know what kinds of creatures, plants and minerals were out there. He assembled a group of men and placed his friends Lewis and Clark at the head of the expedition and sent them out.

Now the expedition was stuck; having gone further than any American had gone before, Lewis and Clark soon realized that they had no way to communicate with any of the Native Americans west of the Mississippi. Hoping that they could find a local trapper that could speak one of the native languages, the expedition stopped at the outpost to recruit someone. Somehow they ran across Toussaint Charbonneau, and initially weren’t happy with him; he was gruff and uncouth and didn’t speak any English, but by communicating with bilingual expedition member Francois LaBiche, he told them that he was the only one that could speak Hidasta fluently.

Well … his wife Sacajawea could speak Hidasta. She could also speak Shoshone.

Hearing that, Lewis and Clark looked at the puzzled Shoshone girl, then immediately insisted that she accompany them, even in her present state; if Sacajawea could speak both Shoshone and Hidasta, that would make it easier to communicate with other tribes, and she likely had a fair knowledge of the terrain in that area. Neither Sacajawea nor Charbonneau spoke English, but they managed to work it out: she could communicate with Charbonneau in Hidasta, Charbonneau would communicate with LaBiche in French, and then LaBiche would communicate in English to Lewis and Clark, and back again. It was a tedious set up, but it worked, and they soon set out.

Initially, there was a lot of skepticism among the men; what was the wisdom in bringing a pregnant woman with them? Lewis and Clark had been uncertain with the idea at first, but they hoped that if any Native American war parties saw Sacajawea and her child amongst the expedition, they would know that the Americans were not there as enemies. At first, Lewis and Clark seemed uninterested in Sacajawea, referring to her in their journals as, “the Indian woman” and, “the squaw.” Eventually, as Sacajawea grew comfortable with the expedition and showed them how resilient, smart and helpful she could be, Lewis and Clark began to refer to her as, “Sac-uh-ja-wee-ah.” Clark grew to like Sacajawea so much that he affectionately gave her the nickname, “Janey,” and sometimes referred to her as such in his journals. (Plus, Clark was a horrifically bad speller—he had fifteen different ways of how to spell “Charbonneau.” Maybe “Janey” was easier too!)

Of all those present in the expedition, Lewis was the most interested in meeting Native Americans, and he was thrilled when Sacajawea told him that they were approaching the territory of her people, the Shoshones. To his disappointment, it was many weeks before they saw any Native Americans at all. On August 11, 1805, the expedition finally spotted a mounted Native American scout on patrol and Lewis was so excited he ran to the scout, shouting, “Ta-ba-bone! Ta-ba-bone!” He thought he was saying was the word for “white man,” not realizing that the word he was using was the word for, “strange enemy.” Lewis was baffled when the scout spun his horse around and galloped away.

A few days later at the expedition’s encampment, a group of Native American warriors cautiously approached the American men. Seeing them, Sacajawea quickly stood up and moved forward to speak to them … but she stopped. She stared at the warriors for a moment, then suddenly shouted in delight and began to dance in joy because these weren’t just any Native Americans—she recognized them as men from her own tribe!

And the chieftain leading them was her own brother Cameahwait!

Cameahwait was shocked speechless when he saw his sister rush up to him and throw a blanket around his shoulders. As the amazed Americans watched, Sacajawea explained to her brother what had happened to her, and that the thirty-three pale skinned strangers (plus York, Clark’s black slave) were friends. More than happy to see his sister alive, Cameahwait greeted the strangers, invited them back to his village and gave them gifts of horses, which were sorely needed. In addition, Cameahwait assigned several guides to help the expedition get to the Rocky Mountains (contrary to popular belief, Sacajawea was not a guide. She was an interpreter and negotiator.)

Even when Sacajawea was heavily pregnant, she never slowed them down and worked just as hard as the men when required. The men all loved her and treated her with respect, helping Lewis and Clark teach her English. As they moved into what would become the Yellowstone Park area, Sacajawea told Lewis they should be careful of the grizzly bears in the area. Having heard about these allegedly “monstrous” bears, Lewis brushed her warning off as a native folktale … but quickly changed his mind when he found himself running for his life while chased by an outraged grizzly—on several occasions! He noted in his journal that the “curiosity of our party is pretty well satisfied with respect to this animal.” Another account has Lewis face to face with an enraged, tomahawk wielding chieftain and Sacajawea rushed in, talking the chief out of it and saving Lewis’s life.

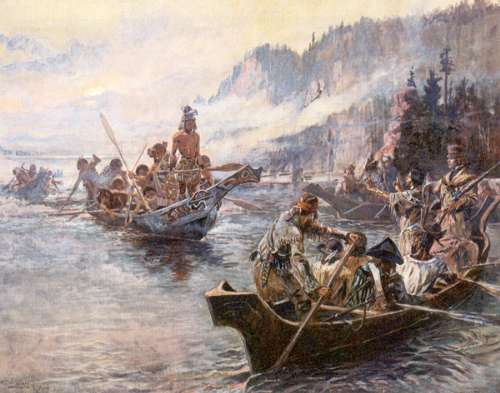

Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia by Charles Marion Russell

On February 11, 1805, Lewis and Clark wrote in their journals that Sacajawea delivered a healthy baby boy, though the labor had been difficult. Charbonneau named his son Jean Baptiste but Clark, who was beside himself with glee at the birth, immediately referred to the baby as “my boy Pompy.” Even stoic Lewis was delighted, and all of the men of the expedition were elated. They all helped care for the boy and called him Pompy or Pomp—probably much to Charbonneau’s irritation.

In May 14, 1805, they boarded back into their shallow boats and sailed up a river tributary. The river was swift moving and choppy, and as Charbonneau tried to sail the boat he, Sacajawea and Pompy were on, the boat slammed against several submerged boulders and tipped, allowing a massive wave of water to wash into it and sweep out a number of tools and journals. As Lewis and Clark shouted for Charbonneau to rescue the journals, Charbonneau, who couldn’t swim, froze in terror. Sacajawea, however, kept a cool head; hefting her baby up high with one arm, Sacajawea lunged over the side of the boat and rapidly scooped up the journals and much of the supplies with her free arm, without anyone telling her to. If they had lost all of that research the expedition would have ultimately been a loss, and, in gratitude, Lewis and Clark named the tributary Sacajawea River.

Sometime afterwards, Sacajawea became extremely sick, suffering from stomach pains so intense that she couldn’t walk or care for Pompy. Worried for both her and the baby, Lewis and Clark tried to dose Sacajawea with some of their own medicine, but the taste was so terrible Sacajawea couldn’t keep it down. Her healing process was slowed even more by Charbonneau constantly dragging her out of bed and forcing her to work. Clark wrote that if Sacajawea died it would be Charbonneau’s fault. Fortunately, Lewis and Clark’s combined efforts pulled Sacajawea through.

Finally reaching the Rocky Mountains, the travel turned out to be much worse than Lewis and Clark had anticipated, and the expedition rapidly ran out of food. Faced with starvation, Sacajawea quickly scoured the sparse plant life, collecting a variety of edible roots that kept the men alive.

Weeks later, finally freed of the Rocky Mountains, the expedition at last reached the Pacific Ocean. “Ocin in view!” Clark wrote excitedly. Shortly after arriving at the Pacific, Lewis and Clark poised a question to the group; winter would be coming soon. If they moved quickly, they might be able to get over the Rocky Mountains again before the worst of the weather hit. Otherwise, they would have to stay here, build a fort and then return home in the springtime. Lewis and Clark called for a vote and included Clark’s slave York and Sacajawea in the process—the first recorded time that a black man and a woman (a Native American woman as well) were allowed to vote as equals to white men.

The vote was unanimous. They stayed and built Fort Clatsop.

With the fort established, Clark wanted to take “Janey and Little Pomp” down to the beach—which was just as well, since Sacajawea seemed to have developed some self-confidence and demanded to see this “monstrous fish” that had washed up on shore. The “monstrous fish” was actually a recently beached dead whale, and when Sacajawea, Clark and the men arrived on the beach, a large group of local Native Americans were there, harvesting the meat from the whale. Seeing these strange looking men, the tribe immediately went on the offensive, but Sacajawea quickly pushed herself through the American men and stood before these new people. The tribe took one look at her and relaxed—no war party would travel with a woman and a child.

In due time the tribe returned with items to trade with the Americans. Among the many things they presented was otter fur, including a beautiful cloak made out of otter pelts. Clark wanted to buy the cloak to give to President Jefferson, and was disappointed when he couldn’t find anything to match the value of the cloak. When Clark’s back was turned, Sacajawea haggled for the cloak, trading her beautiful beaded belt for the fur. (Some accounts claim that Lewis and Clark pressured her to give up the belt.)

The expedition spent the winter there, setting out some time the following spring. In July 1806 as they entered the Rocky Mountains again, Sacajawea suddenly realized that she recognized the area they were in and led them through a pass. The shortcut saved them so much time that Lewis and Clark marked it as Gibbons Pass. Shortly after that, Sacajawea found another shortcut, which Lewis and Clark named Bozman Pass (the exact location of this pass is still being debated.)

On July 25, 1806, the expedition discovered a towering gray rock. Clark was so impressed with the size of the boulder that he named it “Pompy’s Tower” and immediately chiseled, “POMPY’S TOWER JULY 25 1806,” into it. The inscription still remains there.

Upon finally returning to the outpost where they first met, Clark became worried about what would happen to Sacajawea and Pompy; it seems that between the time Charbonneau hit Sacajawea and when they returned home Charbonneau’s behavior had improved enough that Clark considered him a friend, but there must have been something that made Clark concerned enough to offer to adopt Pompy and ask Sacajawea if she would like to live in a real house. Ultimately, Clark invited the family to move to his city of St. Louis, where he would buy them a house and place Pompy in the prestigious St. Louis Academy when he was older. Charbonneau declined the offer at first, but by 1810 the entire family was living in St. Louis.

It’s commonly believed that Sacajawea died young; on December 20, 1812, a trader named John Luttig wrote, “This evening the wife of Charbonneau, a Snake Squaw, died of putrid fever she was good and the best woman in the fort, aged about 25 years.” Charbonneau signed guardianship over to Clark, who adopted Pompy and Sacajawea’s daughter Lizette. There are other reports that Sacajawea left Charbonneau in 1812 and traveled to Wyoming where she became known as Porivo (“Chief Woman”) who died in 1884 and had two sons that could speak Shoshone, English and French. There’s even a memorial marker at the cemetery where Porivo if buried, but there is no real evidence that the woman buried there is Sacajawea.

Today, Sacajawea remains one of the most readily recognizable names in United States history with a number of statues dedicated to her and natural landmarks named in her honor. Most recently in 2000, Sacajawea’s image was placed on the redesigned $1 coin, replacing Susan B. Anthony who had extolled Sacajawea as a prime example of women’s strength.

Sacajawea works referenced:

America’s Women, Gail Collins 2007

Complete Idiot’s Guide to Women’s History, Sonia Weiss et al 2001

Complete Idiot’s Guide to Native American History, Walter C. Fleming 2003

Element Encyclopedia of Native Americans, Adele Nozedar 2013

Native Americans, David Hurst Thomas 2000

The Native Americans, William C. Sturtevant 1991

Sacagawea http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacagawea#Early_life

Touissant Charbonneau http://www.nps.gov/jeff/historyculture/toussaint-charbonneau.htm

Lewis and Clark Expedition http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_and_Clark_Expedition